Texas Flood World Tour

| Worldwide tour by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble | |

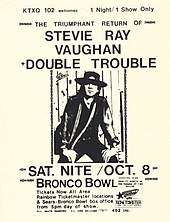

Poster for a concert in Dallas | |

| Location | North America, Europe |

|---|---|

| Associated album | Texas Flood |

| Start date | June 22, 1983 |

| End date | February 25, 1984 |

| Legs | 5 |

| No. of shows | 116 |

| Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble concert chronology | |

The Texas Flood World Tour was a concert tour in North America and western Europe, undertaken by American blues rock band Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble from 1983 to 1984. The band had released their debut album, Texas Flood, a week prior to the tour's beginning. Their sensational talent was demonstrated during a trip to Switzerland in 1982, when they held a jam session with Jackson Browne in a downstairs bar after playing at the Montreux Jazz Festival. Aware of the future opportunities that might accumulate from their performance and the first unsigned act on the festival, Browne offered Vaughan and Double Trouble free use of his personal studio to record Texas Flood. Throughout the tour, the group's career status escalated as their performances continuously amazed and stunned their audiences.

The first leg of the tour took the band to the United States and Canada, and then on to Europe where they toured for two weeks. They then returned to North America, where during a leg that lasted more than three months Vaughan and Double Trouble opened for Men at Work and The Moody Blues. The band then moved on to the Mid-Atlantic, where they concluded the leg before returning to the studio in January 1984, although the tour resumed the following month. The final leg incorporated recurring stops in several cities and a visit to Hawaii, before the band's return home in late February.

The commercial success of the tour, though significant, did not alter the band's modesty, and they continued in this career mindset. However, the tour enabled the group to experience the overseas concert circuit, and gave them massive exposure. In the case of Vaughan this would be ongoing through subsequent tours in the ensuing seven years, before his death in a helicopter crash in August 1990.

Background

Stevie Ray Vaughan was not the only one in his family who was musically talented. Authors Joe Nick Patoski and Bill Crawford refer to several family members,[1] and cites that of Charles LaRue of Chisholm who in 1946,[2] at the age of twenty-three, joined as a trombonist in the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.[3] Biographer Craig Hopkins explain Vaughan's early fascination with music as "the best of all possible worlds in terms of the incentive and opportunity to become a masterful electric guitar player".[4] Other young contemporaries of Vaughan included Eric Johnson, born the same year as Vaughan,[5] and Alan Haynes.[6] Vaughan eventually became recognized among musicians as the future standard for success and promise in blues.[7]

Two children were born to Jimmie Lee "Big Jim" and Martha Jean Vaughan, the oldest, Jimmie Lawrence Vaughan, born March 20, 1951, and the youngest, Stephen "Stevie" Ray Vaughan, born October 3, 1954, in Dallas.[8] Vaughan's musical education was aided by exposure to the constant practicing and playing of Jimmie.[9] When Jimmie was twelve he began to teach himself how to play the guitar, with Vaughan intently observing; according to Vaughan's own account "he made up three songs the first day. He didn't have to try. It just came out".[9] A family friend, Steve Stevenson, noticed that within a few days Jimmie was able to demonstrate what he had learned.[9]

Vaughan himself was a gifted protégé, no less quick to learn than his brother, and was playing the guitar with striking virtuosity by the time he was seventeen. In that year, 1972, Vaughan brought his band Blackbird to Austin to play at Rolling Hills Country Club, later Soap Creek Saloon.[10] Vaughan then joined a band called Krackerjack, during a stint that lasted three months.[11] He had accepted offers from several local bands, but within six years of arriving in Austin, Vaughan and his own group, Double Trouble, were playing at the Rome Inn. Among those present was Manor Downs accountant and future business partner Edi Johnson, who remembered, "I'm not an authority on music—it's whatever turned me on—but this did." After an appearance before the record producer Jerry Wexler, Vaughan and Double Trouble were invited to the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1982,[12] where the purist audience disliked the band's abilities by booing their performance. Patoski and Crawford recounts a similar case of how Muddy Waters received an unfavorable reception at his debut in England in 1958; he reportedly received a negative reaction due to his loud volume.[13] During this overseas visit however, Vaughan and Double Trouble met Jackson Browne on the following night, who offered them free use of his personal studio in Los Angeles, where they recorded a full-length album in November 1982.[14]

As the band gave several performances toward year's end, they began to be noticed by music industry representatives. They were well guaranteed for these engagements—at the end of a two-night stand in Austin, Vaughan and Double Trouble were able to earn more than $7,000 for their efforts.[15] Their career development had progressed when the group signed with Epic Records, and their former momentum was augmented.[16] Thus, the label's approval left Vaughan eager to pursue further opportunities for critical and commercial success.[17] On a trip to New York, Vaughan and Double Trouble played at a concert as the opening act for Bryan Adams, to the evident astonishment of those in attendance.[18]

Tour itinerary

Preparations

In a memorandum to the executives at the southwest branch of Epic, written before the tour, marketing vice president Jack Chase agreed to break Vaughan and Double Trouble out of Texas, who after a branch meeting had said: "The prize is having Stevie Ray Vaughn [sic] on our label and in your bags to promote and sell". Chase asserted that it was his duty to break Vaughan nationally, otherwise "the pride in selling a 'Men at Work' is long gone". He went on to describe Vaughan as a "remarkable artist".[19] Hopkins has suggested that the success of Texas Flood was largely dependent on Chase's expertise in breaking a new artist: "John Hammond has received the most accolades, but without Jack Chase, the record might have been just another of those grapes withering on the vine."[20] However, there is no evidence to suggest that Hammond became less involved in the making of the band's subsequent studio albums; it seems that he trusted Vaughan's abilities as an artist.[21]

Chase wanted to begin the tour as soon as possible—the longer the breakout took, the more competition that would occur. The itinerary he initially planned included the eastern and southwestern United States.[19] The additional legs were only added after the progressing international success of Texas Flood.[22] The plan was for the band to begin the tour by performing nationwide then Western Europe, as well as headlining theater dates in Texas—Vaughan built on the desire from his immediate statewide fan base.[23] Marketing assistance also came from agents Rick Alter and Alex Hodges, whose philosophies and techniques in the major markets would propel the band to perform what eventually became arena tours. These excursions would enable them to receive monetary bonuses that were dependent on specific ticket sale plateaus.[24]

Vaughan and Double Trouble prepared for the tour by performing showcases in Dallas and Houston, which were attended by various musicians, radio station personalities, disc jockeys, record store owners, music critics, and record company executives.[25] As for more general preparation, the band delighted in making promotional appearances, something they never grew to dislike.[26] On tour, even during the busiest traveling days they would fit them in their daily schedule, which would later exhaust the band.[27] Before the tour could begin, Vaughan and Double Trouble needed the support from radio stations, Dallas' Q102-FM in particular.[28] Disc jockey Redbeard had only been receiving negative reactions from listeners in the beginning; nevertheless Redbeard's perseverance to air Texas Flood for an additional two weeks provoked more album sales in the label's seven states of jurisdiction, on the grounds that at least 15,000 units were shipped to record stores, and proper marketing techniques were utilized.[29]

Opening leg (June–August 1983)

The tour's beginning, on June 22, 1983, was slightly discouraging; on the second night Vaughan developed laryngitis, requiring a cancellation of three performances.[30] Vaughan used this time to his advantage by resting his throat.[31] In Philadelphia, on July 8, the band played at Ripley Music Hall, recorded for a radio show broadcast.[32] The next stop was Providence, where they appeared before a capacity audience.[33] The group then moved on to New York, where the band performed for another packed house in Rochester.[34]

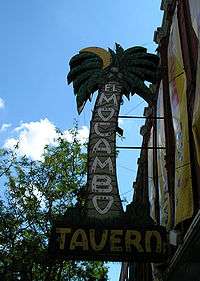

The next extended stop was in Canada. Vaughan and Double Trouble gave four concerts in the region, which included a July 20 appearance at the El Mocambo.[34] From Toronto the band took their newly-purchased tour bus back to New York, where additional concerts were given.[35] Among those present at one of these were tennis players Vitas Gerulaitis and John McEnroe, whom organized a concert as a benefit for the Special Olympics. A review from the concert described it as "one of the lightest turnouts of the season", while Gerulaitis and McEnroe "still cannot lure hordes of teenagers to a concert, even a benefit for a worthy cause". However, the review praised the band: "The concert opened strongly with the ubiquitous Texas guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan leading his trio Double Trouble through a workmanlike set of blues and boogie-woogie."[36]

The group proceeded to the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest and East South Central regions of the US.[37] Returning to Canada they reached Montreal, where a performance was given before over 38,000 people, at Olympic Stadium. The concert also featured The Police, Talking Heads and Peter Tosh, accruing nearly $700,000 in gross revenue.[38] The band proceeded into the west and mid-western US, an area that encompassed Michigan, Illinois, Colorado and California, where they arrived in the regional city, Grand Rapids, on August 11.[39] After two performances at ChicagoFest with opening act Buddy Guy & Junior Wells ("I'll open for them", said Vaughan to Alter),[40] Vaughan and Double Trouble gave a performance as the warm-up for Sammy Hagar on August 19.[41] In late August the band departed for England.[42]

Europe (August–September 1983)

On August 27, 1983 Vaughan and Double Trouble arrived in England. The band hoped to be received positively by the crowd at the Reading Rock Festival in the county of Berkshire. However, a lineup with mainly hard rock and heavy metal artists was not conducive to a positive reception from the audience, so they began throwing bottles of urine. One person who took particular note of this was the band's road crew member Byron Barr, whose journal records the reaction in demeaning terms: "Played Reading Festival. People were rude bastards. They threw bottles full of piss & all kinds of rude shit."[42] Uber Rock writer Andy P's own recollection, written in 2014, was similar: "He kinda stuck out a bit like a sore thumb and like Steel Pulse the day before he caught the attention of the bottle throwers. Unlike Steel Pulse who ended their set early with bottles clanging off their steel drums he persisted with real flair asking the crowd politely, 'I know it's fun but put a stop to it.'"[43]

On August 31 the band traveled to Paris for two shows during which, through the Canadian Recording Industry Association (CRIA), they received their first gold records, which were awarded for selling 50,000 copies of Texas Flood. In Paris they also visited the famous Eiffel Tower, then the Arc de Triomphe—"...where Hitler marched through on horseback. Pretty scary to think that all that shit happened just 40 years or so ago", wrote Barr in his journal.[44] A further concert was given in Berlin on September 4, at a nightclub in the borough of Kreuzberg.[45] The next day Vaughan and Double Trouble's first German television appearance was broadcast: a brief interview with Vaughan and a performance of four songs. These songs were all culled from Texas Flood. The interview featured a male and female host; the male host asked questions in English, and the female host translated Vaughan's responses to German. Hopkins comments that the female host came out wearing Vaughan's trademark flat-brim hat, which he did not appear to find humorous. On September 8 the band arrived in London.[22]

Vaughan and Double Trouble's first London show was at The Venue on Victoria Street. They were advertised as a "special guest at the Reading Rock Festival" with their "new album Texas Flood".[22] The introduction of the group in London proved successful; according to The Guardian, "his technique and command are something quite extraordinary".[46] This was, as former bandmate Billy Alford put it, "just a major drug fest". Referring to Vaughan's escalating substance abuse, Alford said, "I knew he was going to be a star, that he had it. It was just a matter of timing and whether he would kill himself before he got there."[47] Only one more European concert was given, on September 9, at the Paradiso in Amsterdam, from which the band returned to the US for a forthcoming tour of the East Coast.[48]

North America (September–December 1983)

On September 14 Vaughan and Double Trouble arrived in Norfolk, where they played at The Boathouse; a few days later they played an awards show held by WSHE in Miami.[47] Alter was sufficiently confident of their career status to announce the appearances of the group at concerts to be given at Houston Music Hall, Austin City Coliseum and the Bronco Bowl in Dallas in early October.[23] An advertisement for the Dallas concert used the phrase "the triumphant return of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble".[49] The main reason for their return to Texas was the celebration of homecoming concerts in the state. Vaughan had earlier performed extensively in the Texas club circuit, as he had for the previous decade. This allowed his immediate fan base to attend these larger occasions; Vaughan also featured Eric Johnson as the warm-up act for each show.[23]

Manager Chesley Millikin had been effusive in a letter to Chase, dated October 12, that the band would not have had the chance to breakout nationally without the effort of Epic's marketing techniques. He confirmed that Vaughan and Double Trouble would soon return to the studio and learned that Texas Flood was approaching sales of 300,000 units.[23] According to Hodges, many people disliked the idea of their upcoming tour with The Moody Blues, but he reckoned that both bands had a common thread in musical genre, and accordingly organized concerts for October through December, which were deemed a success. Hodges apparently "didn't have any doubt" in Vaughan's ability to command the audience.[24] During a short hiatus in mid-December, the band turned their attention briefly from performing to composing. Among other compositions, they finished two instrumentals, which would be incorporated into the closing shows of the year, which they completed during a return appearance in Norfolk.[50]

United States (February 1984)

The band traveled to New York City for two-and-a-half weeks. No concerts were given by them in this period although there were recording sessions scheduled at the Power Station with Hammond.[51] Layton was effusive about Hammond's presence during the sessions; Hammond, he said, "was kind of like a nice hand on your shoulder", and: "he was a feedback person".[52] Of Hammond he praised his keen ability to identify keeper takes and the elimination of overprocessing. "He was kind of like our gyroscope," said Layton.[53]

The recordings made by Vaughan and Double Trouble during this New York session were later released on Couldn't Stand the Weather, the band's second studio album.[54] On February 4, the band left New York for Nashville. They played in a concert there at Nashville Municipal Auditorium, appearing at the tenth-annual Volunteer Jam, an event organized by Charlie Daniels.[55] They moved on to Knoxville where the group performed at Alumni Memorial Gym on the University of Tennessee campus.[56] The band traveled to Georgia, arriving in Atlanta on February 8, where they gave two shows at Moonshadow Saloon. During the first performance, Vaughan paused during their set and asked an unruly patron to leave the venue.[56] This incident, that Vaughan encountered when faced with disorderly audience members, appears to be one of the few stern orders he made to those who were being disruptive.[57]

The tour through the Midwest continued, with concerts in Missouri and Illinois.[56] Since leaving Chicago, a 28-year-old man named Willie M. "Wimp" Stokes, Jr., the son of a drug kingpin, was shot and killed at a motel in the city less than a week later. Austin musician Bill Carter read about the story in a local newspaper and wrote the song "Willie the Wimp", which he recorded on a demo tape that he gave to Vaughan, who would later include his version of the song on the band's live album.[58] Resuming the tour, the band reached Honolulu on February 25, during which they closed the tour as the warm-up for The Police at Aloha Stadium.[58]

Reception

Commercial

The band had survived a few setbacks, including three canceled shows which were rescheduled due to Vaughan's laryngitis.[31] Although the full extent of the tour's earnings were not highly publicized, or its expenses, the commercial reception of the tour had evidently been considerable. Hopkins confirmed that they had averaged $500 to $950 per show before the release of Texas Flood, but increased to $1,500 by the beginning of the tour.[26] The expenses were certainly somewhat higher; during the Moody Blues tour in October–December 1983, after four months on the road, the band received $5,000 per show, an amount that included additional bonuses dependent on ticket sale plateaus.[59] Layton stated that "I could actually pay my rent and keep my lights turned on and have money to eat on and put gas in my car—that was our real priority in life."[60] He later recounted that in the year prior, they had "very little money, basically broke".[61]

At times, the shows were packed to capacity; in August 1983, near the end of the first North American excursion, the group's performance at The Palace in Los Angeles was a sellout.[41] "As we were pulling up to the club, there was a line all the way around the block," recalled Shannon.[62] Two months later, after having success in Europe, Vaughan and Double Trouble received a portion of the near $75,000 in ticket sale revenue, following an appearance opening for Men at Work in Seattle.[63] However, in December of that year, after the Moody Blues tour concluded, they returned to performing in smaller theaters—they sold-out the Beacon Theatre on December 28.[64] The following year, after studio duties were completed, Vaughan and Double Trouble earned a percentage of the near $155,000 gross revenue after their performance in Nashville.[65] The stability in their successful career status led the band to enjoy making their living by playing music.[66]

Critical response and creative development

In terms of critical reception, while there were some mixed reactions, Vaughan and Double Trouble's public response was well-received, beyond all expectation.[67] The band was now known throughout the United States, Canada and Europe. As well as encounters with other celebrities, the group now had the ability to share the stage with their musical influences; the tour represented, for them, an indicator of success.[68] However, these advantages had been gained at a price; Shannon, in retrospect, noting the stress and strain on the band, had succumbed to "everything you'd want, right there—and for a long time it was fun."[52] However, Vaughan's friend Lew Stokes, while also expressing concerns, concludes that, despite Vaughan's substance abuse, his moral compass had always been prevalent, and the way in which he treated people had never wavered.[27]

Of Vaughan and Double Trouble's music composed during the end of 1983, four of them were released on their next album, Couldn't Stand the Weather. A number of songs were outtakes, including an instrumental and a lyrical piece.[69] The released works include two instrumentals "Scuttle Buttin'" and "Stang's Swang", and two lyrical pieces "Couldn't Stand the Weather" and "Honey Bee". Vaughan's creative progress is likewise reflected in the songs released on Couldn't Stand the Weather, which, according to Hopkins, quickly outpaced the sales of Texas Flood.[54] The album includes Vaughan's first attempt at instrumental jazz, "Stang's Swang".[51] The tour thus saw Vaughan's confirmation of his mastery over the electric guitar.[64] This was evidenced in his hometown, on June 16, when a number of radio VIPs attended the Texas Flood record release party. They were frankly skeptical about Vaughan's performance skills, believing them to only be feasible in the studio.[28]

Aftermath

Despite the extent of their financial earnings from the tour, Vaughan and his wife Lenny continued to live in their modest house in Austin.[70] However, travel and public appearances dominated the next two years of Vaughan's life. In March 1984 the band was on the move again, this time to North America, Europe, Australasia and Japan, remaining on the road until May 1985.[71] Within the next month Vaughan and Double Trouble left for another tour—with Reese Wynans who was now the band's keyboardist.[72] They were away for over ten months, and took a break in May 1986, to change their management team.[73] A second visit to Europe, from September until October 1986, was the last of the exhaustive touring schedules;[74] Vaughan's new personal assistant, Timothy Duckworth, had concerns about his escalating substance abuse, which ultimately proceeded to threaten his life—and now Shannon's, himself immersed by addiction.[75]

Tour dates

| Date | City | Country | Venue | Opening Act(s) | Attendance | Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg 1: North America[76][77][78] | ||||||

| June 22, 1983 | Bloomington | United States | Jake's | N/A | N/A | |

| June 23, 1983 | Cleveland | Pirate's Cove | ||||

| June 28, 1983 | Cincinnati | Bogart's | Ray Fuller and the Bluesrockers | |||

| June 29, 1983 | St. Louis | Mississippi Nights | ||||

| July 1, 1983 | Milwaukee | Marcus Amphitheater | Short Stuff, Truc | |||

| July 2, 1983 | Quincy | Quinsippi Island | ||||

| July 3, 1983 | Chicago | Metro | George Faber and Stronghold | |||

| July 6, 1983 | Asbury Park | Asbury Park Convention Hall | ||||

| July 7, 1983 | New York City | First City | Eve Moon | |||

| July 8, 1983 | Philadelphia | Ripley Music Hall | ||||

| July 9, 1983 | Providence | Lupo's Heartbreak Hotel | ||||

| July 10, 1983 | Boston | The Paradise | The Lost Tropics | |||

| July 12, 1983 | Poughkeepsie | The Chance | ||||

| July 13, 1983 | Auburn | Charlie's | ||||

| July 14, 1983 | Rochester | Red Creek Inn | ||||

| July 15, 1983 | Buffalo | Rooftop Skyroom | ||||

| July 16, 1983 | Toronto | Canada | CNE Bandshell | |||

| July 18, 1983 | Montreal | Spectrum de Montréal | ||||

| July 19, 1983 | Ottawa | Barrymore's | ||||

| July 20, 1983 | Toronto | El Mocambo | ||||

| July 22, 1983 | Rome | United States | Colman's | |||

| July 23, 1983 | New York City | Pier 84 | ||||

| July 24, 1983 | Scotia | Radio City | ||||

| July 25, 1983 | New Haven | Toad's Place | Current | |||

| July 27, 1983 | Washington, D.C. | The Bayou | Bob Margolin | |||

| July 28, 1983 | Pittsburgh | The Decade | Loan Sharks | |||

| July 30, 1983 | Detroit | Saint Andrew's Hall | Street Light Knights | |||

| July 31, 1983 | Dayton | Gilly's | ||||

| August 1, 1983 | Louisville | Stage II | Lonnie Mack | |||

| August 3, 1983 | Montreal | Canada | Olympic Stadium Amphitheatre | 38,617 / 40,000 | $690,416 | |

| August 11, 1983 | Lowell | United States | Lowell Showboat Amphitheater | N/A | N/A | |

| August 12, 1983 | Chicago | Soldier Field | Vanessa Davis Band, Eddie Taylor | |||

| August 13, 1983 | Buddy Guy & Jr. Wells, Clark Street | |||||

| August 15, 1983 | Colorado Springs | Rose's | Dave Drynan, Red Perry and Walter Chase | |||

| August 16, 1983 | Denver | Rainbow Music Hall | ||||

| August 19, 1983 | Sacramento | Cal Expo Grandstands | Y&T | 15,003 / 25,000 | $262,177 | |

| Berkeley | Keystone | N/A | N/A | |||

| August 20, 1983 | San Francisco | The Stone | Northern Rockers | |||

| August 21, 1983 | Palo Alto | Keystone | ||||

| August 22, 1983 | Los Angeles | The Palace | Hodge Brothers Band | |||

| August 23, 1983 | Huntington Beach | Golden Bear | ||||

| Leg 2: Europe[79] | ||||||

| August 27, 1983 | Reading | England | Little John's Farm | N/A | N/A | |

| September 1, 1983 | Paris | France | Rock and Roll Circus | |||

| September 2, 1983 | ||||||

| September 4, 1983 | Berlin | Germany | Sektor | |||

| September 7, 1983 | Hamburg | Fabrik | ||||

| September 8, 1983 | London | England | The Venue | |||

| September 9, 1983 | Amsterdam | Netherlands | Paradiso | Harry Muskee Gang | ||

| Leg 3: North America[80][81][82] | ||||||

| September 14, 1983 | Norfolk | United States | The Boathouse | N/A | N/A | |

| September 15, 1983 | Richmond | Much More | Johnny Sportcoat and the Casuals | |||

| September 16, 1983 | York | York Expo Center | ||||

| September 17, 1983 | Benson | Scott Lake Pavilion | The Spongetones, Control Group | |||

| September 20, 1983 | Charlotte | P.B. Scott's Music Hall | ||||

| September 21, 1983 | Stone Mountain | Harlow's | The Heartfixers, The Road Ducks | |||

| September 22, 1983 | Jacksonville | Playground South | ||||

| September 23, 1983 | Miami | James L. Knight Center | Mitch Ryder | |||

| September 25, 1983 | Cocoa Beach | Brassy's Night Club | The Road Ducks | |||

| September 26, 1983 | Orlando | Tom's Point After | ||||

| September 27, 1983 | Sarasota | Playground South | ||||

| September 28, 1983 | Clearwater | Mr. T's Club 19 | ||||

| September 30, 1983 | Gainesville | UF Bandshell | Artimus Pyle Band | |||

| October 1, 1983 | Destin | Nightown | The Road Ducks | |||

| October 2, 1983 | New Orleans | McAlister Auditorium | G.T. & the Trustees | |||

| October 6, 1983 | Houston | Houston Music Hall | Eric Johnson and the Avenue | |||

| October 7, 1983 | Austin | Austin City Coliseum | ||||

| October 8, 1983 | Dallas | Bronco Bowl | ||||

| October 11, 1983 | Portland | Veterans Memorial Coliseum | ||||

| October 12, 1983 | Seattle | Seattle Center Arena | 6,000 / 6,000 | $74,719 | ||

| October 13, 1983 | Vancouver | Canada | Pacific Coliseum | N/A | N/A | |

| October 15, 1983 | Edmonton | Northlands Coliseum | ||||

| October 17, 1983 | Hartford | United States | Hartford Civic Center | |||

| October 18, 1983 | Worcester | Centrum in Worcester | 10,391 / 11,000 | $133,855 | ||

| October 19, 1983 | Buffalo | Buffalo Memorial Auditorium | N/A | N/A | ||

| October 21, 1983 | Philadelphia | The Spectrum | 12,832 / 15,000 | $151,372 | ||

| October 22, 1983 | East Rutherford | Brendan Byrne Arena | N/A | N/A | ||

| October 23, 1983 | Portland | Cumberland County Civic Center | ||||

| October 25, 1983 | Baltimore | Baltimore Civic Center | ||||

| October 26, 1983 | Pittsburgh | Civic Arena | ||||

| October 28, 1983 | Cincinnati | Riverfront Coliseum | ||||

| October 29, 1983 | Ann Arbor | Crisler Arena | ||||

| October 30, 1983 | Rockford | MetroCentre | ||||

| October 31, 1983 | Saint Paul | St. Paul Civic Center | ||||

| November 1, 1983 | Cedar Rapids | Five Seasons Center | ||||

| November 2, 1983 | Omaha | Omaha Civic Auditorium | ||||

| November 4, 1983 | Dallas | Reunion Arena | 8,816 / 9,663 | $94,627 | ||

| November 6, 1983 | Austin | Frank Erwin Center | 6,462 / 12,673 | $67,095 | ||

| November 7, 1983 | Houston | The Summit | N/A | N/A | ||

| November 20, 1983 | Seattle | Seattle Center Coliseum | ||||

| November 21, 1983 | Portland | Veterans Memorial Coliseum | ||||

| November 23, 1983 | Vancouver | Canada | Pacific Coliseum | |||

| November 24, 1983 | Edmonton | Northlands Coliseum | ||||

| November 25, 1983 | Calgary | Olympic Saddledome | ||||

| November 27, 1983 | Denver | United States | McNichols Sports Arena | |||

| November 28, 1983 | Casper | Casper Events Center | ||||

| November 30, 1983 | Tempe | ASU Activity Center | ||||

| December 1, 1983 | San Diego | Montezuma Hall | The Paladins | |||

| December 2, 1983 | Santa Barbara | Campbell Hall | ||||

| December 3, 1983 | Inglewood | The Forum | ||||

| December 4, 1983 | San Francisco | Kabuki Nightclub | Ron Thompson and the Resistors, Pamela Rose and Wild Kingdom | |||

| Leg 4: United States[83][84] | ||||||

| December 27, 1983 | Washington, D.C. | United States | Wax Museum Nightclub | Bob Margolin | N/A | N/A |

| December 28, 1983 | New York City | Beacon Theatre | The Outlaws, The Nighthawks | |||

| December 29, 1983 | Upper Darby | Tower Theater | The Outlaws | |||

| December 30, 1983 | Baltimore | Famous Ballroom | Skip Castro Band | |||

| December 31, 1983 | Norfolk | The Boathouse | ||||

| Leg 5: United States[85][86][87] | ||||||

| February 4, 1984 | Nashville | United States | Nashville Municipal Auditorium | Grinderswitch, Rodney Crowell | 9,900 / 9,900 | $154,665 |

| February 5, 1984 | Knoxville | Alumni Memorial Gym | The Heartfixers | N/A | N/A | |

| February 7, 1984 | Charlotte | P.B. Scott's Music Hall | Robert Cray Band | |||

| February 8, 1984 | Atlanta | Moonshadow Saloon | The XL's | |||

| February 10, 1984 | Athens | Georgia Hall | The Heartfixers | |||

| February 11, 1984 | Carbondale | Shryock Auditorium | ||||

| February 12, 1984 | Kansas City | Uptown Theater | The Belairs | |||

| February 15, 1984 | Normal | Braden Auditorium | ||||

| February 16, 1984 | Peoria | Second Chance | ||||

| February 17, 1984 | Chicago | Embassy Ballroom | ||||

| February 18, 1984 | Ida Noyes Hall | |||||

| February 25, 1984 | Honolulu | Aloha Stadium | 31,653 / 50,000 | |||

See also

References

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 9

- ↑ Los Angeles Times (2006), p. B7

- ↑ Cooper (2008), p. 64

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 319

- ↑ Prown & Sharken (2003), p. 19

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 119

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. xi

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), pp. 6, 8

- 1 2 3 Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 10

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), pp. 45–6

- ↑ Hopkins (2010), pp. 67–70

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 145

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 148

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 149

- ↑ Patoski & Crawford (1993), p. 150

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 9

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 17

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 16

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 19

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 18

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 11

- 1 2 3 Hopkins (2011), p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 Hopkins (2011), p. 38

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 39

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 22, 24

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 23

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 28

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 22

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 19, 23

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 24–5

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 25

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 26

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 26–7

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 27

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 27–8

- ↑ Holden (1983)

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 29–30

- ↑ "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 34. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. August 20, 1983. p. 44. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 31–3

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 31

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 32

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 33

- ↑ H, Johnny; P, Andy (December 7, 2014). "Stevie Ray Vaughan And Double Trouble: 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection'". Uber Rock: Kick Ass Rock 'n' Roll. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 34

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 34–5

- ↑ Brown (1983), p. 8

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 36

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 36–7

- ↑ "Stevie Ray Vaughan Double Trouble 1983 Bronco Bowl Dallas Handbill". The Heart of Rock and Roll. 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 44–5

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 46

- 1 2 Interviews by Dan Jackson, July 26–27, 1997: Doyle Bramhall, Jimmie Vaughan, Chris Layton, Tommy Shannon

- ↑ In The Studio, Album Network, 1993, Redbeard

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 59

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 47

- 1 2 3 Hopkins (2011), p. 48

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 48, 145

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 49

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 39, 45

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 45

- ↑ "Success in Disguise" (DVD documentary), Live at Montreux: 1982 & 1985.

- ↑ Guitar World, August 2000, "Pride and Joy," Andy Aledort; "The Lost Interviews," Andy Aledort

- ↑ "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 45. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 5, 1983. p. 48. ISSN 0006-2510.

- 1 2 Hopkins (2011), p. 44

- ↑ "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 96 no. 6. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. February 18, 1984. p. 37. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ↑ Guitar World, May 2000, "Rise & Shine," Andy Aledort

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 24

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 29–32

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 301

- ↑ Barr, Byron (2013). "Stevie Ray Vaughan". Vintage Texas Blues. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 53–98

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), p. 99

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 99–132

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 144–7

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 136, 146

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 24-33

- ↑ First leg boxscore data:

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 34. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. August 20, 1983. p. 44. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 36. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 3, 1983. p. 41. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ↑ First leg opening act references:

- "Summerfest schedule". The Milwaukee Journal. July 1, 1983. p. 6.

- "1983 Metro Chicago Flyer (second thumbnail)". WorthPoint Corporation. 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- "The Chance ticket stub". Facebook. n.d. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "Bio". Connecticut Singer-Songwriter-Guitarist-Bart Bryant. 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "Night Life". The Pittsburgh Press. 100 (35). July 28, 1983. p. D5.

- LeLievre (2013)

- Walek (1983), p. 22

- Jarvis (1983), p. B1

- "Events". The Stanford Daily. August 19, 1983. p. 15.

- "Calendar: Pop Music—Concerts". Los Angeles Times. August 21, 1983. p. 72.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 33-36

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 36-43

- ↑ Third leg boxscore data:

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 45. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 5, 1983. p. 48. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 95 no. 48. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 26, 1983. p. 43. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ↑ Third leg opening act references:

- Mahin (1983)

- "Something's going on..." (PDF). The Pendulum. 10 (2). Elon. September 15, 1983. p. 12.

- "Harlow's ticket stub". WorthPoint Corporation. 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "Personnel/Bios". The Roadducks. 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- Haldin (1983), p. 2C

- "McAlister Auditorium newspaper advertisement". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. October 1, 1983.

- "Montezuma Hall newspaper advertisement". The Daily Aztec. 65 (66). UC San Diego. November 30, 1983. p. 6.

- "List of concerts promoted by Bill Graham". SugarMegs Audio. 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 43-45

- ↑ Fourth leg opening act references:

- "Jazz / Folk / Rock Concerts, Personal Appearances, Etc". The New Yorker. Advance Publications. December 26, 1983. p. 7.

- "Tower Theater newspaper advertisement". eBay. 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- "In concert". The Baltimore Sun. 294 (37). December 30, 1983. p. C1.

- ↑ Hopkins (2011), pp. 47-49

- ↑ Fifth leg boxscore data:

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 96 no. 6. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. February 18, 1984. p. 37. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Harada, Wayne (February 26, 1984). "Record 31,653 see Police in action". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. A7.

- ↑ Fifth leg opening act references:

- "AB Boxscore: Top Concert Grosses" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 96 no. 6. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. February 18, 1984. p. 37. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "Georgia Hall newspaper advertisement". The Red and Black. University of Georgia. February 9, 1984. p. 7.

Sources

- Brown, Mick (September 10, 1983). "Weekend Arts". The Guardian. London.

- Cooper, Sid (2008). It Looked So Good in the Window. Bloomington: iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 978-0-5955-2140-1.

- Haldin, Ken (September 23, 1983). "Concert Listings". Ocala Star-Banner.

- Holden, Stephen (July 25, 1983). "'Tennis Rock': McEnroe and Gerulaitis". The New York Times Digital Archive. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- Hopkins, Craig (2010). Stevie Ray Vaughan – Day by Day, Night After Night: His Early Years, 1954–1982. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4234-8598-8.

- Hopkins, Craig (2011). Stevie Ray Vaughan – Day by Day, Night After Night: His Final Years, 1983–1990. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61774-022-0.

- Jarvis, Elena (August 12, 1983). "Stevie Ray Vaughan tends the blues with his guitar". The Gazette Telegraph. Colorado Springs.

- LeLievre, Roger (April 18, 2013). "Hot '80s Ann Arbor ska band SLK releases old tunes digitally for new audience". The Ann Arbor News. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- Mahin, Bruce P. (September 16, 1983). "Much More concert review". Richmond Times-Dispatch.

- "Obituaries". Los Angeles Times. November 8, 2006.

- Patoski, Joe Nick; Crawford, Bill (1993). Stevie Ray Vaughan: Caught in the Crossfire. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-16069-5.

- Prown, Pete; Sharken, Lisa (2003). Gear Secrets of the Guitar Legends: How to Sound Like Your Favorite Players. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-879-30751-X.

- Walek, Gordon (August 6, 1983). "ChicagoFest VI at Soldier Field". The Daily Herald. 111 (296). Arlington Heights.