Tea in the United Kingdom

Since the eighteenth century, the United Kingdom has been one of the world's greatest tea consumers, with an average annual per capita tea supply of 1.9 kg (4.18 lbs).[1] The British Empire was instrumental in spreading tea from China to India; British interests controlled tea production in the subcontinent. Tea, which was an upper-class drink in continental Europe, became the infusion of every social class in Great Britain throughout the course of the eighteenth century and has remained so. Tea is a prominent feature of British culture and society.[2]

In both the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, the drinking of tea is so varied that it is quite hard to generalise. While it is usually served with milk, it is not uncommon to drink it black or with lemon, with sugar being a popular addition to any of the above. Strong tea, served in a mug with milk and sugar, is a popular combination known as builder's tea.

History

The rise in popularity of tea between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries had major social, political, and economic implications for Great Britain. It defined respectability and domestic rituals, supported the rise and dominance of the British Empire, and contributed to the rise of the Industrial Revolution by supplying both the capital for factories and calories for labourers.[3] It also demonstrates the power of globalization and imperialism to transform a country and shape it into the modern society it is known as today. Tea remains a popular drink in Britain in the modern day and is still considered to be the epitome of British ritual and identity.

Historiography

Historians debate the causes of tea’s popularity and many attribute it to one or two factors, but a range of different factors are apparent at different times. Ukers argues in All About Tea: Volume I that the rise in popularity of tea in Great Britain was largely due to tea’s reputation among men as a medicinal drink that could cure a wide array of ailments, along with its burgeoning presence in the coffeehouses where elite men congregated.[4] As for tea’s popularity among women, he briefly acknowledges that Princess Catherine of Braganza, future queen consort of England, made tea fashionable among aristocratic women, but largely attributes its popularity to its ubiquity in the medical discourse of seventeenth century. Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger trace tea’s popularity back to three distinct groups in Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World. These groups were virtuosi, merchants, and elite female aristocrats.[5] They argue that the influence of these three groups combined launched tea as a popular beverage in Great Britain. Smith, in his article "Complications of the Commonplace: Tea, Sugar, and Imperialism" differs from Ukers and Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger in that he argues that tea only became popular once sugar was added to the drink and tea with sugar became associated with a domestic ritual that indicated respectability.[6] Mintz, in both “The Changing Roles of Food in the Story of Consumption” and Sweetness and Power, agrees and disagrees with Smith. Mintz acknowledges that sugar played a monumental role in the rise of tea, but contradicts Smith’s connection of tea to respectability.[7] While Smith argues that tea first became popular in the home, Mintz believes tea first became popular in the workplace, as people drank tea during the workday for its warm sweetness and stimulating properties.[8] It was later that it entered the home and became an “integral part of the social fabric.”[3]

Seventeenth century: a medicinal and luxury import

Early mentions

The history of European interactions with tea dates back to the mid-sixteenth century. The earliest mention of tea in European literature was by Giambattista Ramusio, a Venetian explorer, as Chai Catai or “Tea of China” in 1559.[9] Tea was mentioned several more times in various European countries afterwards, but Jan Hugo van Linschooten, a Dutch navigator, was the first to write a printed reference of tea in 1598 in his Discours of Voyages.[10]

However, it was several years later, in 1615, that the earliest known reference to tea by an Englishman took place in a letter exchanged between Mr. R. Wickham, an agent for the British East India Company stationed at Japan to a Mr. Eaton, who was stationed in Macao, China.[11] In this letter, Wickham asked Eaton to send him “a pot of the best sort of chaw,”[11] phonetically how one would write chàh, the local (Cantonese) dialect word for tea. Another early reference to tea appears in the writings of trader Samuel Purchas in 1625.[12] Purchas describes how the Chinese consume tea as “the powder of a certaine herbe called chia of which they put as much as a walnut shell may contain, into a dish of Porcelane, and drink it with hot water.”[12] In 1637, Peter Mundy, a traveller and merchant who came across tea in Fujian, China, wrote, "chaa – only water with a kind of herb boyled in it".[13]

Sale of tea begins

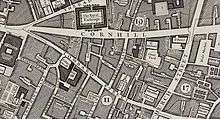

Though there were a number of early mentions, it was several more years before tea was actually sold in England. Green tea exported from China was first introduced in the coffeehouses of London shortly before the Stuart Restoration (1660).

Thomas Garway (or Garraway), a tobacconist and coffee house owner, was the first person in England to sell tea as a leaf and beverage at his London coffeehouse in Exchange Alley in 1657.[14][15] He had to explain the new beverage in a pamphlet. Immediately after Garway began selling it, the Sultaness Head Coffee House began selling tea as a beverage and posted the first newspaper advertisement for tea in Mercurius Politicus on 30 September 1658.[16] The announcement proclaimed "That Excellent, and by all Physicians approved, China drink, called by the Chinese, Tcha, by other nations Tay alias Tee, ...sold at the Sultaness-head, ye Cophee-house in Sweetings-Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London". [17][16]

In London "Coffee, chocolate and a kind of drink called tee" were "sold in almost every street in 1659", according to Thomas Rugge's Diurnall.[18] Tea was mainly consumed by upper and mercantile classes: Samuel Pepys, curious for every novelty, tasted the new drink on 25 September 1660 and recorded the experience in his diary: "I did send for a cup of tee, (a China drink) of which I had never had drunk before".

The British East India company made its first order for the importation of tea in 1667 to their agent in Bantam, and two canisters of tea weighing 143 lbs 8 oz arrived from Bantam in 1669.[19] In 1672, a servant of Baron Herbert in London sent his instructions for tea making, and warming the delicate cups, to Shropshire:

The directions for the tea are: a quart of spring water just boiled, to which put a spoonful of tea, and sweeten to the palate with candy sugar. As soon as the tea and sugar are in, the steam must be kept in as much as may be, and let it lie half or quarter of an hour in the heat of the fire but not boil. The little cups must be held over the steam before the liquid be put in.[20]

The earliest English equipages for making tea date to the 1660s. Small porcelain tea bowls were used by the fashionable; they were occasionally shipped with the tea itself. Tea-drinking spurred the search for a European imitation of Chinese porcelain, first successfully produced in England at the Chelsea porcelain manufactory, established around 1743-45 and quickly imitated. See tea set.

A medicinal drink

The first factor that contributed to the rise in popularity of tea was its reputation as a medical drink. Tea first became labeled as a medical drink in 1641 by the Dutch physician Nikolas Dirx, who wrote under the pseudonym "Nicolas Tulp"[21] – though he was also a director of the Dutch East India Company, so his praise of tea was likely a marketing tactic.[22] In his book Observationes Medicae, he claimed that "nothing is comparable to this plant" and that those who use it are "exempt from all maladies and reach an extreme old age."[23] He goes into detail on the specific merits of tea, such as curing “headaches, colds, ophthalmia, catarrh, asthma, sluggishness of the stomach, and intestinal troubles.”[23] Thomas Garway, the first English shopkeeper to sell tea, published a broadsheet in 1660 titled "An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality, and Vertues of the Leaf TEA" which also praised tea's medical benefits. Garway claims that “the Drink is declared to be most wholesome, preserving in perfect health until extreme Old Age", as well as "maketh the body active and lusty", "helpeth the Headache", "taketh away the difficulty of breathing", "strengtheneth the Memory", and "expelleth infection".[24]

There were many more published works on the health benefits of tea, including those by Hartlib in 1657, Bontekoe in 1678, Povey in 1686, and Tryon in the 1690s,[25][26][27] and the Royal College of Physicians debated whether any of the exotic new hot drinks would "agree with the Constitutions of our English bodies".[28] In 1667, Pepys noted that his wife was taking tea on medical advice – "a drink which Mr Pelling the Pottecary tells her is good for her colds and defluxions". John Locke, the famous English philosopher, developed a fondness for tea after spending time with Dutch medical men in the 1680s.[29] Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger refer to these men as “virtuosi”: scientists, philosophers, and doctors who first took an interest in tea and contributed to its early popularity as a pharmaceutical.[30] But, such as with the case of Tulp, some of these men may have been influenced by Indies companies and merchants who wished to create a market for tea. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that these writings about the so-called health benefits of tea contributed to rise in popularity of tea in England.

Popularity among aristocrats

According to Ellis, Coulton, Maugher, “tea was six to ten times more expensive than coffee” in the 1660s, making it an extremely expensive and luxurious commodity.[31] Moreover, the proliferation of works on the health benefits of tea came at a time when people in the upper classes of English society began to take an interest in their health.

In 1660, two pounds and two ounces of tea bought from Portugal were formally presented to Charles II by the British East India Company.[32] The drink, already common in Europe, was a favourite of his new Portuguese bride, Catherine of Braganza, who introduced it at court after she married Charles II in 1662, and made it fashionable among the ladies of the court as her temperance drink of choice.[22][33] Catherine of Braganza's use of tea as a court beverage, rather than a medicinal drink, influenced its popularity in literary circles around 1685.[34] Whenever it was consumed in the court, it was “conspicuously on display” so as to show it off.[30]

Accordingly, tea drinking became a central aspect of aristocratic society in England by the 1680s, particularly among women who drank it while gossiping in the home.[35] Catherine of Braganza’s introduction of tea to ladies was significant because it made tea an acceptable drink for both sexes, when it easily could have been categorized as a men’s drink if it had remained only available in the coffeehouses that only men frequented. Wealthy ladies’ desire to show off their luxurious commodities in front of other ladies also increased demand for tea and made it more popular. Another factor that made tea desirable among the elite crowd was the addition of sugar, another luxurious commodity which was already well-established among the upper classes.

Eighteenth century: a marker of middle-class upward mobility and patriotism

Colonial trade

While tea slowly became more common in coffeehouses during the second half of the seventeenth century, the first tea shop in London did not open until the early eighteenth century. Thomas Twining's tea shop has been claimed as the first, opening in 1706, and still remained at 216 Strand, London. However, 1717 is also given as a date for the first tea shop.[36] In between tea’s earliest mentions in England and its widespread popularity little over a century later, many factors contributed the craze for this previously unknown foreign commodity.

Tea would not have become the English staple it is known as if not for the increase in its supply that made it more accessible. Between 1720 and 1750 the imports of tea to Britain through the British East India Company more than quadrupled.[37] By 1766, exports from Canton stood at six million pounds on British boats, compared with 4.5 on Dutch ships, 2.4 on Swedish, 2.1 on French.[38] Veritable "tea fleets" grew up. Tea was particularly interesting to the Atlantic world not only because it was easy to cultivate but also because of how easy it was to prepare and its ability to revive the spirits and, reputedly, cure mild colds.[39]

When tea was first introduced to England, the British East India Company was not directly trading with China and merchants relied on tea imports from Holland.[40] Because this tea was so expensive and difficult to get, there was very little demand for it, except among the elite who could afford it and made special orders. It was not until after 1700 that the British East India Company began to trade regularly with China and ordering tea, though not in large quantities.[41] Smith argues that the tea trade was actually a side effect of the silk and textile trade because these were the Chinese commodities that were most desired at the time.[41] In 1720, however, Parliament banned the importation of finished Asian textiles and traders began to focus on tea instead.[41] This new focus marked a turning point for the English tea trade and is arguably why tea became more popular than coffee. Once the British East India company focused on tea as its main import, tea soon attained price stability. Conversely, the price of coffee remained unpredictable and high, allowing tea to grow in popularity before coffee became more accessible.[42] Furthermore, the rising demand for tea and sugar was easily met with increased supply as the tea industry grew in India, which prevented sharp price increases that would have discouraged people from buying it.[43] In fact, the price of tea actually fell as it was becoming more popular among the upper-middle and middle classes. The significant drop in tea’s price between 1720 and 1750 was a major turning point for tea in England. The increase in supply of tea was one of the most important factors that boosted its popularity in Britain and opened up the world of tea to new levels of society.

Introduction of milk and sugar

Though by the beginning of the eighteenth century tea was already gaining popularity on its own, the addition of sugar helped tea’s popularity to soar. The English began adding sugar to their tea between 1685 and the early eighteenth century.[44] At this time, sugar was already being used to enhance the flavor of other foods among the elite and had a reputation as an ostentatious luxury.[45] Because both tea and sugar had status implications it made sense to drink them together,[46] and the growth in the import of tea parallels that of sugar in the eighteenth century,[47] which itself was booming due to the growth of sugar plantations in the Americas.[48] But, as previously mentioned, the elite classes of England were starting to care more about their health and literature on the unhealthiness of sugar was beginning to circulate in the late seventeenth century.[49] Adding sugar to tea, however, was seen as an acceptable way to consume sugar because it suggested that “one had the self-control to consume sugar in a healthy way.”[49] Sugar also masks tea’s bitterness, so it simply made tea more desirable because it tasted better. As the supply of both tea and sugar grew during the early eighteenth century, the combination of the two commodities became more universal and increased the popularity and demand for both products. Black tea overtook green tea in popularity in the 1720s when sugar and milk were added to tea, a practice that was not done in China.

Popularity among the middle classes

_-_Tea_Time_-_18th_century.jpg)

Because tea began in Britain as a luxury for the super-rich, it had a reputation in the eighteenth century as a high-class commodity. But as prices slowly fell, more people at the middle levels of society had access to it. Accordingly, drinking tea became associated with respectability among upwardly mobile middle-class people.[50] When people drank tea, they were expected to possess certain manners and behave in a particular way.[50] Soon, drinking tea became a domestic ritual among families, colleagues, and friends who were just wealthy enough to afford it, which also increased demand.[43] The association between tea and respectability became so ingrained in both British and Irish culture that it reached a point where it could not go out of fashion.[49] Tea-drinking among these groups was also soon considered patriotic. Because the British East India Company had a monopoly over the tea industry in England, tea became more popular than coffee, chocolate, and alcohol.[51] Tea was seen as inherently British and tea-drinking was encouraged by the British government because of the revenue gained from taxing tea.[52] Unlike coffee and chocolate, which came from the colonies of Britain’s rivals in various regions of the world, tea was produced in a single massive colony and served as a means of not only profit, but colonial power.[52][49] Mintz goes so far as to argue that the combination of ritualization and increased production in the British colonies was how tea became inherently British.[53]

As the British continued to import more and more tea throughout the eighteenth century, tea slowly went from a respectable commodity consumed by the well-mannered classes in domestic rituals to an absolute necessity in the British diet, even among the poor working classes. John Hanway, an eighteenth-century social reformer, observed the widespread consumption of tea by the poor in 1767. He described "a certain lane ... where beggars are often seen ... drinking their tea", as well as "laborers mending their roads drinking their tea" and tea "in the cups of haymakers".[54] Just two centuries after the first appearance of tea in English society as a beverage for aristocrats, tea had become so widely popular and available that those at the absolute bottom of the social hierarchy were consuming it as their beverage of choice. It was at this point that tea became universal among all levels of society. Fernand Braudel asked, "is it true to say the new drink replaced gin in England?"[55]

Nineteenth century: universal consumption

Adoption by the working classes

By the nineteenth century, tea’s popularity had reached the working class and it was soon considered an everyday necessity among poor labourers. According to the Scottish historian David MacPherson, tea had become cheaper than beer in the early nineteenth century.[56] Furthermore, sugar had also become extremely cheap by this time and the two were almost always consumed together.[57] Though the price of coffee had also gone down by this point, tea was the preferred drink because, unlike coffee, it still tasted good when diluted, which is often how the poor consumed it in order to save money.[58]

Tea had other attractions as well. Drinking a hot, sweet beverage transformed their meals, which generally consisted of dry bread and cheese, and made them go down more easily.[3] The warm beverage was especially appealing given Britain’s cold and wet climate.[3][53] Further, tea helped alleviate some of the consequences of the urbanization that accompanied the industrial revolution: drinking tea required boiling the water, thereby killing water-borne diseases like dysentery, cholera, and typhoid.[59]

However, the poor consumed tea very differently to the well-mannered ritual adopted by the upper classes. According to Mintz, “tea-drinking among the poor probably began in connection with work, not in the home”,[60] and some scholars suggest that tea played a role in the British Industrial Revolution.[59] Day labourers brewed their tea out in the open and brought their tea equipment with them to work, as opposed to the private domestic ritual that had previously surrounded tea-drinking.[3] Afternoon tea possibly became a way to increase the number of hours labourers could work; the stimulants in the tea, accompanied by the calorie boost from the sugar and accompanying snacks, would give workers energy to finish the day's work.[53][59]

Cultivation in India

The popularity of tea occasioned the furtive export of slips, a small shoot for planting or twig for grafting to tea plants, from China to British India and its commercial cultivation there, beginning in 1840.

Between 1872 and 1884 the supply of tea to the British Empire increased with the expansion of the railway to the east. The demand, however, was not proportional, which caused the prices to rise. Nevertheless, from 1884 onward, due to innovation in tea preparation, the price of tea dropped and remained relatively low throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

Soon afterwards London became the centre of the international tea trade.[61] With high tea imports also came a large increase in the demand for porcelain. The demand for tea cups, pots and dishes increased to go along with this popular new drink.[39]

Gender

Roger Fulford argues that tea rooms benefited women in the Victorian era, in that these neutral public spaces were instrumental in the "spread of independence" for women and their struggle for the vote.[62] Paul Chrystal characterizes tea rooms as "popular and fashionable, especially with women", providing them a dignified and safe place to meet and eat – and strategize on political campaigns.[63]

Tea today

In 2003, DataMonitor reported that regular tea drinking in the United Kingdom was on the decline.[64] There was a 10.25 per cent decline in the purchase of normal teabags in Britain between 1997 and 2002.[64] Sales of ground coffee also fell during the same period.[64] Britons were instead drinking health-oriented beverages like fruit or herbal teas, consumption of which increased 50 per cent from 1997 to 2002. A further, unexpected, statistic is that the sales of decaffeinated tea and coffee fell even faster during this period than the sale of the more common varieties.[64] Declining tea sales were matched by an increase in espresso sales.[65] Nevertheless, tea still remains an extremely popular drink and is still engrained in British culture and society.

In 1787, Twinings Tea created its logo, still in use today, which is thought to be the world's oldest commercial logo that has been in continuous use since its inception.[66] Under Associated British Foods since 1964, Stephen Twining now represents the company's tenth generation. In 2006, Twinings celebrated its 300th anniversary with a special tea and associated tea caddies. Twining's is a Royal Warrant holder (appointed by HM The Queen).

Brewing the tea

Even very slightly formal events can be a cause for cups and saucers to be used instead of mugs. A typical semi-formal British tea ritual might run as follows (the host performing all actions unless noted):[67]

- The kettle is brought to a rolling boil (with fresh water to ensure good oxygenation which is essential for proper diffusion of the tea leaves).[68]

- Enough boiling water is swirled around the teapot to warm it and then poured out.

- Add loose tea leaves (usually black tea) or tea bags, always added before the boiled water.

- Fresh boiling water is poured over the tea in the pot and allowed to brew for 2 to 5 minutes while a tea cosy may be placed on the pot to keep the tea warm.[69]

- A tea strainer is placed over the top of the cup and the tea poured in, unless tea bags are used. Tea bags may be removed, if desired, once desired strength is attained.

- White sugar and milk (in that order) may be added, usually by the guest.

- The pot will normally hold enough tea so as not to be empty after filling the cups of all the guests. If this is the case, the tea cosy is replaced after everyone has been served. Hot water may be provided in a separate pot, and is used only for topping up the pot, never the cup.

The question of milk

—One of Orwell's eleven rules for making tea from his essay "A Nice Cup of Tea", appearing in the London Evening Standard, 12 January 1946.[70]

Whether to put milk into the cup before or after the tea has been a matter of debate since at least the mid-twentieth century; in his 1946 essay "A Nice Cup of Tea", author George Orwell wrote, "tea is one of the mainstays of civilisation in this country and causes violent disputes over how it should be made".[71] Whether to put tea in the cup first and add the milk after, or the other way around, has split public opinion, with Orwell stating, "indeed in every family in Britain there are probably two schools of thought on the subject".[71]

Another aspect of the debate are claims that adding milk at the different times alters the flavour of the tea (for instance, see ISO 3103 and the Royal Society of Chemistry's "How to make a Perfect Cup of Tea".[72]) Some studies suggest that the heating of milk above 75 degrees Celsius (adding milk after the tea is poured, not before) does cause denaturation of the lactalbumin and lactoglobulin.[73] Other studies argue brewing time has a greater importance.[74] Regardless, when milk is added to tea, it may affect the flavour. In addition to considerations of flavour, the order of these steps is thought to have been, historically, an indication of class. Only those wealthy enough to afford good-quality porcelain would be confident of its being able to cope with being exposed to boiling water unadulterated with milk.[75]

A further point of discussion on when to add milk is how it affects the time taken for the liquid to reach a drinkable temperature. While adding milk first will cause an initial drop in temperature which leads to a more shallow cooling curve (thus slower cooling) while also increasing volume (which would slightly increase the surface area through which the tea could lose heat), one study noted that adding milk first leads to the tea retaining heat out of all proportion with these effects. The major mechanism by which hot tea cools is not conduction or radiation but evaporative loss which is affected by the physical properties of the milk.[footnote 1] The study concluded that lipids in milk prevent water evaporating so rapidly thus retaining heat longer.[footnote 2]

Drinking etiquette

There are opinions as to the proper manner in which to drink tea when using a cup and saucer.[76] Historically, during the 1770s and 1780s, it was fashionable to drink tea from saucers. Saucers were deeper than is the current fashion and so more similar to bowls like their Chinese antecedents.[77] If one is seated at a table, the proper manner to drink tea is to raise the teacup only, placing it back into the saucer in between sips. When standing or sitting in a chair without a table, one holds the tea saucer with the off hand and the tea cup in the dominant hand. When not in use, the tea cup is placed back in the tea saucer and held in one's lap or at waist height. In either event, the tea cup should never be held or waved in the air. Fingers should be curled inwards; despite popular belief in the United States, no finger should extend away from the handle of the cup.[67]

Tearoom

Shortly before the Restoration of 1660, Chinese green tea was introduced to the coffeehouses of London,[78] which were significant places of social interaction, distinct from pubs, taverns, and inns. The owner of the coffeehouse explained the new beverage in a pamphlet: "That Excellent, and by all Physicians approved, China drink, called by the Chinese, Tcha, by other nations Tay alias Tee, ...sold at the Sultaness-head, ye Cophee-house in Sweetings-Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London". [79] "Coffee, chocolate and a kind of drink called tee" were "sold in almost every street [in London] in 1659", according to Thomas Rugge's Diurnall.[80] Tea was mainly consumed by upper and mercantile classes: Samuel Pepys, curious for every novelty, tasted the new drink in 1660 and recorded the experience in his diary for 25 September: "I did send for a cup of tee, (a China drink) of which I had never had drunk before".[81]

Hogarth's Gin Lane was not the first warning about working class drunkenness. One response to the perception of widespread dissolution was the temperance movement, which promoted tea as a healthful alternative to alcohol of any sort. From the 1830s many new cafes and coffeehouses opened, as a place to socialise that was not a pub or an inn. Tearooms were also significant since they provided a place where women in the Victorian era could take a meal — without a male escort — without risk to their reputations. Tea rooms catered for all classes of society.

In 1864, the Aerated Bread Company opened the first of what would grow to be known as A.B.C. Tea Shops. The idea came from a London-based "manageress" at ABC "who'd been serving gratis tea and snacks to customers of all classes, [and] got permission to put a commercial public tearoom on the premises."[82] By 1923, the A.B.C. tea shops had 250 branches,[83] second only to J. Lyons and Co.. Lyons Corner Houses started in 1894, and soon became the leading chain of tea rooms; their waitresses were known as "nippies" for the speed of their work.

In 1878 Catherine Cranston opened the first of what became a chain of Miss Cranston's Tea Rooms in Glasgow, Scotland, providing elegant well-designed social venues which for the first time provided for well-to-do women socialising without male company. They proved widely popular. She engaged up and coming designers, becoming a patron of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. He designed the complete building of the Willow Tearooms, a strikingly modern exterior as well as a series of interesting interior designs. Similar establishments became popular throughout Scotland. As of 2016, the Glasgow Willow Tearooms are being restored.

Roger Fulford argues that tea rooms benefitted women, in that these neutral public spaces were instrumental in the "spread of independence" for women and their struggle for the vote.[84] Paul Chrystal characterises tea rooms as "popular and fashionable, especially with women", providing the a dignified and safe place to meet and eat, and strategise on political campaigns.[85]

There is a long tradition of tea rooms within London's hotels. For example, Brown's Hotel has been serving tea for over 170 years [86] From the 1880s fine hotels in both the US and the UK featured tea rooms and tea courts, and by 1910 they had begun to host afternoon tea dances as dance crazes swept both countries.

Tea rooms of all kinds were widespread in Britain by the 1950s, but in the following decades cafés became more fashionable, and tea rooms became less common. Nonetheless, there are still plenty of places that offer the opportunity to enjoy afternoon tea, a luxurious light meal of savoury snacks (tea sandwiches) and small pastries. A less formal alternative is a cream tea, particularly popular in the West Country: a scone with jam and clotted cream. Another possibility is the high tea, hot savoury food as the day's final (but relatively early) meal. There are plenty of regional variations: in Scotland, teas are usually served with a scones, pancakes, crumpets and other cakes.

Tea rooms can be found in most towns and many villages.

Tea as a break

British workers by law, have the right to a minimum of a twenty-minute break in a shift of six hours; government guidelines describe this as "a tea or lunch break".[87] More informally, this is known as elevenses, i.e. a couple of hours before the midday meal, traditionally served at 11 am. Builder's tea in a mug is typical of a quick tea break in the working day.

Tea as a meal

Tea is not only the name of the beverage but also of a light meal. Anna Maria, Duchess of Bedford, is credited with its creation, circa 1840, to ward off hunger between luncheon and dinner, as the latter was being served later and later.{[fact}} The notion of cakes or a light meal with tea passed to teahouses or tearooms. While these establishments have declined in popularity since the Second World War, there are still many to be found in the countryside. In the West Country, cream teas are a speciality: scones, clotted cream and jam accompany the drink. Afternoon tea, in contemporary British usage, usually indicates a special occasion, perhaps in a hotel dining room, with savoury snacks (tea sandwiches) as well as small sweet pastries.

A social event to enjoy tea together, usually in a private home, is a tea party.

"Tea" (sometimes "high tea") can also mean the savoury, hot early evening meal. This usage is common in working-class British English and in Northern England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland). See Tea as the evening meal.

Tea cards

.jpg)

In the United Kingdom, a number of varieties of loose tea sold in packets from the 1940s to the 1980s contained tea cards. These were illustrated cards roughly the same size as cigarette cards and intended to be collected by children. Perhaps the best known were Typhoo tea and Brooke Bond (manufacturer of PG Tips), the latter of whom also provided albums for collectors to keep their cards in. In the brand named Brooke Bond Dividend D, the card was a dividend ("divvy") against the cost of the tea.

Some renowned artists were commissioned to illustrate the cards, including Charles Tunnicliffe. Many of these card collections are now valuable collectors' items.

A related phenomenon arose in the early 1990s when PG Tips released a series of tea-based pogs, with pictures of cups of tea and chimpanzees on them. Tetley's tea released competing pogs but never matched the popularity of the PG Tips variety.

See also

Drinks

- Earl Grey tea, a classic English blended tea, flavoured with bergamot essential oil

- English breakfast tea

- Prince of Wales tea blend

- Gunfire (drink), a cocktail made of tea and rum served in the British Army

Food

Appliances

- Teasmade, an English appliance that combines a kettle and a teapot to make tea automatically by alarm clock

- Brown Betty (teapot), an iconic type of teapot made from British red clay, known for being rotund and glazed with brown manganese

- Cube teapot, a heavy-duty type of teapot invented for making tea on ships

- Tea set, the pot, sugar bowl, milk jug, etc.

Other

- List of tea companies#United Kingdom

- London Tea Auction, 1679-1998

- TV pickup, a daily spike in power consumption in the UK due to the use of electric kettles

- Tea lady

- National Tea Day

Footnotes

- ↑ Water molecules whose temperature is far above the average temperature of the tea escape and it is only these above average temperature molecules that have sufficient energy to escape the surface of the tea. As the tea's temperature drops the rate of evaporation, and thus rate of heat loss by evaporation, also drops and evaporative loss becomes a minor mechanism.

- ↑ For this reason Chinese tea cups come with lids to retain heat as it is common practise in China to add tea leaves to a cup and brew in the cup and so the water temperature must be kept high for sufficient time. Also, insulated cups/travel mugs for hot beverages come with lids as it is anticipated that the beverage will be imbibed some while after being heated.

References

- ↑ "Food Balance Sheets". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ↑ "A very British beverage: Why us Brits just love a cuppa". Express. 23 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mintz 1993, p. 266

- ↑ Ukers 1935, pp. 23–46

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, pp. 31–76

- ↑ Woodruff D. Smith, "Complications of the Commonplace: Tea, Sugar, and Imperialism". Journal of Interdisciplinary History (Autumn 1992), 259-277.

- ↑ Mintz 1993, pp. 261–270

- ↑ Mintz 1985, pp. 110–117

- ↑ Giambattista Ramusio, Navigatione et Viaggi, Vol. II, Venice, 1559, in Ukers 1935, pp. 23–24

- ↑ Jan Hugo Van Linschooten, Discours of Voyages, London, 1598, in Ukers 1935, p. 26

- 1 2 Ukers 1935, p. 37

- 1 2 Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes, Vol. III, London, 1625, in Ukers 1935, p. 38

- ↑ Chrystal, Paul (October 17, 2014). Tea: A Very British Beverage. Amberley Publishing Limited.

- ↑ Ukers 1935, p. 38

- ↑ Mair, Victor H.; Hoh, Erling (2009). The True History of Tea. Thames & Hudson. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1.

- 1 2 Ukers 1935, p. 41

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall (2004). Empire: the rise and demise of the British world order. p. 11.

- ↑ Rugge's Diurnall is preserved in the British Library (Add. MSS. 10,116-117); it was published as The diurnal of Thomas Rugg, 1659-1661, William Lewis Sachse ed., (1961).

- ↑ M P John MacGregor. Commercial Statistics. a Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs, Navigation, Port, and Quarantine Laws, and Charges, Shipping, Imports and Exports, and the Monies, Weights, and Measures of All Nations. p. 47. ISBN 9781130006230.

- ↑ Smith, W. J., ed., Herbert Correspondence, University of Wales (1963), pp. 204-5 no. 353, John Read to Richard Herbert of Oakly Park, Ludlow, 29 June 1672.

- ↑ Ukers 1935, p. 31

- 1 2 Smith, 268.

- 1 2 Nicolas Tulp, Obersaciones Medicae, Amsterdam, 1641, in Ukers 1935, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Thomas Garway, “An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality, and Vertues of the Leaf TEA,” c. 1660, preserved in the British Museum, in Ukers 1935, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, pp. 32, 34

- ↑ Thomas Povey, Esq., “A Famous Tea Manuscript of 1686,” Oct. 20, 1686, in Ukers 1935, p. 40

- ↑ Smith, 296.

- ↑ Shapin, Steven (July 30, 2015). "Pretence for Prattle". The London Review of Books. 37 (15): 17–18. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, p. 43

- 1 2 Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, p. 31

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, p. 36

- ↑ Richard, Lord Braybrooke, ed., note in The Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, F.R.S., vol. I :109.

- ↑ Mintz 1993, p. 110

- ↑ Wilhelm, Kendra Hunt. "Tea Comes to England". Tea.

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, p. 39

- ↑ Ukers 1935, p. 46

- ↑ Sir George Staunton's figure, starting in 1693, is quoted, e.g., in Walvin, James. 1997. "A taste of empire, 1600-1800". (cover story). History Today 47.1 (2001: 11).

- ↑ Braudel 1981:251.

- 1 2 Guerty, P. M.; Switaj, Kevin (1 April 2004). "Tea, porcelain, and sugar in the British Atlantic world". OAH Magazine of History. 18 (3): 56–59. doi:10.1093/maghis/18.3.56.

- ↑ Ellis, Coulton & Mauger 2015, p. 37

- 1 2 3 Smith, 273.

- ↑ Smith, 274.

- 1 2 Smith, 275.

- ↑ Smith, 263.

- ↑ Smith, 266.

- ↑ Smith, 270.

- ↑ "Tea". In Our Time. 29 April 2004. BBC Radio 4.

- ↑ Smith, 271.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, 277.

- 1 2 Smith, 276.

- ↑ Mintz 1985, p. 113

- 1 2 Mintz 1985, p. 114

- 1 2 3 Mintz 1985, p. 110

- ↑ Jonas Hanway, 1767, in Mintz, 117.

- ↑ Braudel 1981:252.

- ↑ David MacPherson, The History of European Commerce with India (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, 1812), 132, in Mintz 1993, p. 264

- ↑ Mintz 1993, p. 264

- ↑ Mintz 1985, p. 112

- 1 2 3 Macfarlane, Alan. "Tea and the Industrial Revolution" (MOVie).

- ↑ Mintz 1993, p. 265

- ↑ Nguyen, D. T.; Rose, M. (1987). "Demand for tea in the UK 1874-1938: An econometric study". Journal of Development Studies. 24 (1): 43. doi:10.1080/00220388708422054.

- ↑ Votes for Women 1957, quoted in Tea: A Very British Beverage by Paul Chrystal 2014.

- ↑ Chrystal, Paul (2014). Tea: A Very British Beverage.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Britons have less time for tea". Food & Drink. 16 June 2003. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Espresso cups outsell mugs". The Telegraph. 11 Nov 2011.

- ↑ Standage, T. (2005). A History of the World in Six Glasses. New York: Walker. p. 202.

- 1 2 "All About British Tea". URBANARA Infographic. Guide to British Tea Time.

- ↑ "The perfect cup". Twinings.

- ↑ Alleyne, Richard (15 Jun 2011). "How to make the perfect cup of tea – be patient". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "How to make a perfect cuppa: put milk in first". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- 1 2 George Orwell, Ian Angus, Sheila Davison (1998). "The Complete Works of George Orwell: Smothered under journalism, 1946". p. 34. Secker & Warburg

- ↑ "How to make a Perfect Cup of Tea" (PDF). Royal Society of Chemistry. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-11.

- ↑ Rowland, S. J. (December 1933). "The Heat Denaturation of Albumin and Globulin in Milk". Journal of Dairy Research. 5 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1017/S0022029900000911.

- ↑ Kyle, J. A.; Morrice, P. C.; McNeill, G.; Duthie, G. G. (2007). "Effects of Infusion Time and Addition of Milk on Content and Absorption of Polyphenols from Black Tea". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (12): 4889–4894. doi:10.1021/jf070351y.

- ↑ Beverly Dubrin (1 October 2010). Tea Culture: History, Traditions, Celebrations, Recipes & More. Charlesbridge Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-60734-363-9. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Sapsted, David (8 Aug 2007). "Tea room outlaws biscuit dunking". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Titus, Susan. "Tea: A Brief History". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Mair, Victor H.; Hoh, Erling (2009). The True History of Tea. Thames & Hudson. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, Empire: the rise and demise of the British world order, (2004:11).

- ↑ Rugge's Diurnall is preserved in the British Library (Add. MSS. 10,116-117); it was published as The diurnal of Thomas Rugg, 1659-1661, William Lewis Sachse ed., (1961)

- ↑ Richard, Lord Braybrooke, ed., note in The Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, F.R.S., vol. I :109.

- ↑ Brandt, Pamela Robin. “Tea for View, View for Tea,” Miami New Times. October 17, 2002. (Retrieved 2009-05-08). See also: “英格兰饮茶风俗由何而来? (二),” British Council China. August 8, 2007. (Retrieved 2009-05-08).

- ↑ "Aerated Bread Company (ABC)", London Metropolitan Archives. National Archives. ACC/2910, 1869-1885. (Retrieved 2009-05-08).

- ↑ Votes for Women 1957, quoted in Tea: A Very British Beverage by Paul Chrystal 2014.

- ↑ Chrystal, Paul (2014). Tea: A Very British Beverage.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Luxury Hotels - 5 Star Hotels and Resorts - Rocco Forte". Browns Hotel. Archived from the original on 2007-10-28.

- ↑ "Rest breaks at work". gov.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

Sources

- Ellis, Markman; Coulton, Richard; Mauger, Matthew (2015). Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World. Islington, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books.

- Mintz, Sidney W. (1993). "The Changing Roles of Food in the Study of Consumption". In Brewer, John; Porter, Roy. Consumption and the World of Goods. New York: Routledge.

- Mintz, Sidney W. (1985). Sweetness and Power. New York: Penguin Books.

- Ukers, William H. (1935). All About Tea: Vol. I. New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal.

Further reading

- Julie E. Fromer. A Necessary Luxury: Tea in Victorian England (Ohio University Press, 2008), 375pp

- Hobhouse, Henry (1987). Seeds of Change: Six Plants that Transformed Mankind. Harper. ISBN 978-0060914400.

External Links

- Tea, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Huw Bowen, James Walvin & Amanda Vickery (In Our Time, Apr. 29, 2004)