Taq Kasra

| Taq Kasra إيوان المدائن | |

|---|---|

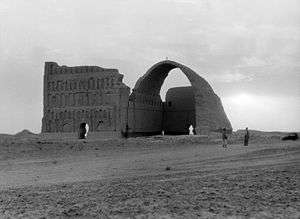

Ruins of Ctesiphon (from the United States Library of Congress) | |

| Location | Ctesiphon, Al-Mada'in, Iraq |

| Coordinates | 33°5′37″N 44°34′51″E / 33.09361°N 44.58083°ECoordinates: 33°5′37″N 44°34′51″E / 33.09361°N 44.58083°E |

| Height | 37 m (121 feet) |

| Built | ca. 3rd-6th century AD |

| Architectural style(s) | Persian architecture |

Location in Ctesiphon, modern Iraq | |

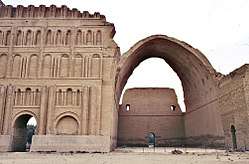

Tāq Kasrā, also transcribed as Taq-i Kisra, Taq-e Kesra, (Persian: طاق کسری) and Ayvān-e Kasrā[1] (Persian: ایوانِ کسری); meaning Iwan of Khosrow) are names given to the remains of a ca. 3rd–6th century Sasanian Persian monument, which is sometimes called the Archway of Ctesiphon.[2] It is located near the modern town of Salman Pak, Iraq. It is the only visible remaining structure of the ancient city of Ctesiphon. The archway is considered a landmark in the history of architecture,[1] and is the largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world.[3]

History

The exact time of construction is not known with certainty. Some historians believe the founder is Shapour I who ruled Persia from 242 to 272 AD[4] and some other believe that construction possibly began during the reign of Anushiruwan the Just (Khosrow I)[5] after a campaign against the Byzantines in 540 AD.[6] The arched iwan hall, open on the facade side, was about 37 meters high 26 meters across and 50 meters long, the largest man-made, free standing vault constructed until modern times.[7]

The arch was part of the imperial palace complex. The throne room—presumably under or behind the arch—was more than 30 m (110 ft) high and covered an area 24 m (80 ft) wide by 48 m (160 ft) long. The top of the arch is about 1 meter thick while the walls at the base are up to 7 meters thick.[6] It is the largest vault ever constructed in the world. The catenary arch was built without centring.[6] In order to make this possible a number of techniques were used.[6] The bricks were laid about 18 degrees from the vertical which allowed them to be partially supported by the rear wall during construction.[6] The quick drying cement used as mortar allowed the fresh bricks to be quickly supported by those that were previously laid.[6]

The Taq Kasra is now all that remains above ground of a city that was, for seven centuries—from the 2nd century BC to the 7th century AD—the main capital of the successor dynasties of the Persian empire: Parthians and Sassanids. The structure left today was the main portico of the audience hall of the Sassanids who maintained the same site chosen by the Parthians and for the same reason, namely proximity to the Roman Empire, whose expansionist aims could be better contained at the point of contact.

The structure was captured by the Arabs during the conquest of Persia in AD 637.[6] They then used it as a mosque for a while until the area was gradually abandoned.[6]

The monument is also the subject of a poem by Khaqani who visited the ruins in the twelfth century.[1]

Modern era

In 1851 French artist Eugène Flandin visited and studied the structure with Pascal Coste[8] who remarked "the Romans had nothing similar or of the type".[9]

In 1888, a serious flood demolished the greater part of the edifice. [10]

In 1940, Roald Dahl, then undergoing pilot training at RAF Habbaniya near Baghdad[11] took an award-winning photograph using a Zeiss camera of the Arch of Ctesiphon in Iraq which was subsequently auctioned by the Dahl family to raise funds for the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre.[12] The photo made £6,000. In his autobiography Boy he writes:

- You may not believe it, but when I was eighteen I used to win prizes and medals from the Royal Photographic Society in London, and from other places like the Photographic Society of Holland. I even got a lovely big bronze medal from the Egyptian Photographic Society in Cairo, and I still have the photograph that won it. It is a picture of one of the so-called Seven Wonders of the World, the Arch of Ctesiphon in Iraq. This is the largest unsupported arch on earth and I took the photograph while I was training out there for the RAF in 1940. I was flying over the desert solo in an old Hawker Hart biplane and I had my camera round my neck. When I spotted the huge arch standing alone in a sea of sand, I dropped one wing and hung in my straps and let go of the stick while I took aim and clicked the shutter. It came out fine.[12]

The monument was in the process of being rebuilt by Saddam Hussein's government in the course of the 1980s, when the fallen northern wing was partially rebuilt. All works, however, stopped after the 1991 Persian Gulf War. The current Iraqi government is cooperating with the University of Chicago's Diyala Project to restore the site.[13]. The Ministry of Culture has also invited a Czech company to restore the site.

Documentary film

In 2017 Pejman Akbarzadeh, based in the Netherlands, made the first documentary film about Taq Kasra. The monument was in serious danger of ISIS attacks in 2015-2016 and this was the main motivation for the documentary maker to travel to Iraq twice and film the arch before it was potentially destroyed.[14]The film explores the history and architecture of Taq Kasra with prolific scholars and archaeologists in various countries.[15]

Gallery

- Taq Kasra Gallery

1824 drawing by Captain Hart

1824 drawing by Captain Hart Picture from 1864

Picture from 1864 Picture from 1932

Picture from 1932

1923 Iraqi postage stamp, featuring the arch

1923 Iraqi postage stamp, featuring the arch Iraqi officials and American military officers discuss plans to renovate the existing structures.

Iraqi officials and American military officers discuss plans to renovate the existing structures. The National Museum of Iran, the architecture of which is adopted from that of Taq-i Kasra

The National Museum of Iran, the architecture of which is adopted from that of Taq-i Kasra

See also

- Taq Kasra: Wonder of Architecture

- Persian Empire

- Sasanians

- Al-Ukhaidir Fortress, Abbasid structure in Iraq showing influences from Taq-i Kisra

- Hatra

- Persian architecture

References

- 1 2 3 Keall, E. J. "AYVĀN-E KESRĀ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ Farrokh, Kaveh. Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey, 2007

- ↑ , Chris, ed. (2008). Taq-I-Kasra (Arch of Ctesiphon). worldheritagesite.

- ↑ Schmidt, J.H. "L'expédition de Ctésiphon en 1931-1932". Persee. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ Because of the vicissitudes of historical transmission, eventually no less than four Sasanian rulers were quoted as its builders: Shapur I (241–273), Shapur II (310–379), Khosrau I Anushirvan (531–579) and Khosrau II Parvez (590–628). Kurz, Otto (1941). "The Date of the Ṭāq i Kisrā". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (New Series). 73 (1): 37–41. JSTOR 25221709.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Reade, Dr Julian (1999). Scarre, Chris, ed. The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient world The Great Monuments and How they were Built. Thames & Hudson. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-500-05096-1.

- ↑ Wright, G. R. H., Ancient building technology vol. 3. Leiden, Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV. 2009. 237. Print.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre. "Ctesiphon, palais sassanide". achemenet. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ "Master Builders: Influence of Sassanid Architecture Reached far Beyond their Borders - Kaveh Farrokh". kavehfarrokh.com. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ↑ Taq Kasra: The Archway of Ctesiphon - http://www.amusingplanet.com/2016/03/taq-kasra-archway-of-ctesiphon.html

- ↑ GOING SOLO by Roald Dahl

- 1 2 http://www.e-reading-lib.com/bookreader.php/1010577/Dahl_-_Moi_Boy.html

- ↑ Diyala Project

- ↑ "Taq Kasra: Wonder of Architecture; directed by Pejman Akbarzadeh". SOAS. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Taq Kasra Documentary Film". TaqKasra.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taq-i Kisra. |