Struma (river)

| Struma (Струма), Strymónas (Στρυμόνας) | |

|---|---|

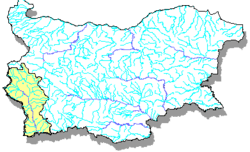

The course of the Struma in Bulgaria and Greece | |

| Country | Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source |

The south slopes of Vitosha, Bulgaria 2,180 m (7,150 ft) |

| River mouth |

Aegean Sea, Greece 40°47′9″N 23°50′56″E / 40.78583°N 23.84889°ECoordinates: 40°47′9″N 23°50′56″E / 40.78583°N 23.84889°E |

| Length | 415 km (258 mi) |

| Discharge |

|

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 17,330 km2 (6,690 sq mi) |

The Struma or Strymónas (Bulgarian: Струма [ˈstrumɐ]; Greek: Στρυμόνας [striˈmonas]; Turkish: (Struma) Karasu [kaɾaˈsu], 'black water') is a river in Bulgaria and Greece. Its ancient name was Strymṓn (Greek: Στρυμών [stryˈmɔːn]). Its drainage area is 17,330 km2 (6,690 sq mi), of which 50% in Greece, 36% in Bulgaria and 14% in Macedonia.[1] It takes its source from the Vitosha Mountain in Bulgaria, runs first westward, then southward, enters Greek territory at the Kula village. In Greece it is the main waterway feeding and exiting from Lake Kerkini, a significant centre for migratory wildfowl. The river flows into the Strymonian Gulf in Aegean Sea, near Amphipolis in the Serres regional unit. The river's length is 415 kilometres (258 miles) (of which 290 kilometres (180 mi) in Bulgaria, making it the country's fifth-longest).

Parts of the river valley belong to a Bulgarian coal-producing area, more significant in the past than nowadays. The Greek portion is a valley which is dominant in agriculture, being Greece's fourth-biggest valley. The tributaries include the Konska River, the Dragovishtitsa, the Rilska River, the Blagoevgradska Bistritsa, the Sandanska Bistritsa, the Strumitsa and the Angitis.

Etymology

The river's name comes from Thracian Strymón, derived from Proto-Indo-European *srew- "stream",[2] akin to English stream, Old Irish sruaimm "river", Polish strumień "stream", Lithuanian straumuoe "fast stream", Greek ῥεῦμα (rheũma) "stream", Albanian rrymë "water flow", shri "rain".

The name Strymón, was a hydronym in ancient Greek mythology, referring to a mythical Thracian king that was drowned in the river.[3] Strymón was also used as a personal name in various regions of Ancient Greece during the 3rd century BC.[4]

History

In 437 BC, the ancient Greek city of Amphipolis was founded near the river's entrance to the Aegean, at the site previously known as Ennea Hodoi ('Nine roads'). When Xerxes I of Persia crossed the river during his invasion in 480 BC he buried alive nine young boys and nine maidens as a sacrifice to the river god.[5] The forces of Alexander I of Macedon defeated the remnants of Xerxes' army near Ennea Hodoi in 479 BC. In 424 BC the Spartan general Brasidas after crossing the entire Greek peninsula sieged and conquered Amphipolis. According to the ancient sources, the river was navigable from its mouth up to the ancient (and today dried) Cercinitis lake, which also favored the navigation; and thus was formed in antiquity an important waterway that served the communication between the coasts of Strymonian Gulf and the Thracian hinterland and almost to the city of Serres.[6]

The decisive Battle of Kleidion was fought close the river in 1014 between the Bulgarians under Emperor Samuel and the Byzantines under Emperor Basil II and determined the fall of the First Bulgarian Empire four years later. In 1913, the Greek Army was nearly surrounded in the Kresna Gorge of the Struma by the Bulgarian Army during the Second Balkan War, and the Greeks were forced to ask for armistice.

The river valley was part of the Macedonian front in World War I. The ship Struma, which took Jewish refugees out of Romania in World War II and was torpedoed and sunk in the Black Sea, causing nearly 800 deaths, was named after the river.

Gallery

Struma at Kresna Gorge.

Struma at Kresna Gorge. Struma near the city of Blagoevgrad in winter.

Struma near the city of Blagoevgrad in winter. Lion of Amphipolis; Via Egnatia, west side of the Strymonas river.

Lion of Amphipolis; Via Egnatia, west side of the Strymonas river. Greek soldiers at Strymon during WWI.

Greek soldiers at Strymon during WWI.

Honour

- Struma Glacier on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Struma River.

Notes

- ↑ Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment, Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change, p. 86

- ↑ Radislav Katičic', Ancient Languages of the Balkans, Part One. Mouton, Paris 1976, p. 144.

- ↑ Pierre Grimal, Classical mythology. Wiley-Blackwell, 1990. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- ↑ Antoninus Liberalis, Celoria Francis, The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis. A translation with commentary. Routledge, 1992. ISBN 978-0-415-06896-3.

- ↑ Herodotus 7,114 . The history may be Greek slander, though, as human sacrifice is not known as an Iranian cultic practice.

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Historical Geography of Eastern Macedonia during the Antiquity (= Makedonikí bibliothíki, 49). Society of Macedonian Studies, Thessaloniki 1976, p. 16 ff.

ISBN 960-7265-16-5 (in Greek; online text).

Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A History of Serres (in the Ancient and Roman Times). Thessaloniki 1999, pp. 55–60 (in Greek; website of the municipality of Serres).

External links

- Livius.org: Strymon