Stratioti

| Stradioti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 15th to 18th centuries |

| Type | Mercenary unit |

| Role | Light cavalry |

The Stratioti or stradioti (Italian: stradioti, stradiotti, Greek: Στρατιώτες/stratiotes, Albanian: Stratiotët) were mercenary units from the Balkans recruited mainly by states of southern and central Europe from the 15th century until the middle of the 18th century.[2]

Name

The Greek term stratiotis/-ai (στρατιώτης/-αι) was in use since classical antiquity with the sense of "soldier".[3] The same word was used continuously in the Roman and Byzantine period. The Italian term stradioti could therefore be a loan from the Greek word stratiotai (Greek: στρατιώται), i.e. soldiers.[4] Alternatively, it derives from the Italian word strada ("street"), meaning "wayfarer".[5] The Albanian stradioti of Venice were also called cappelletti (sing. cappelletto) because of the small red caps they wore.[6]

History

The stradioti were recruited in Albania, Greece, Dalmatia, Serbia and later Cyprus.[7][8][9][10] Most of the names were Albanian, such as Gjon, Gjin, Merkur, Arbnor, Ilir, Agron etc., but a good number of the names were of Greek origin, such as Palaiologos, Spandounios, Laskaris, Rhalles, Comnenos, Psendakis, Maniatis, Spyliotis, Alexopoulos, Psaris, Zacharopoulos, Klirakopoulos, and Kondomitis. Others seemed to be of South Slavic origin, such as Soimiris, Vlastimiris, and Voicha.[5] Also among their leaders were members of some old Byzantine noble families such as the Palaiologi and Comneni.[5][11]

Stratioti in European countries

Republic of Venice and Kingdom of Naples (Italy)

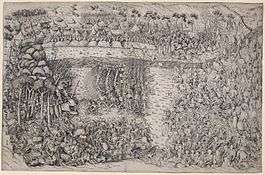

The Republic of Venice first used stratioti in their campaigns against the Ottoman Empire and, from c. 1475, as frontier troops in Friuli. Starting from that period, they began to almost entirely replace the Venetian light cavalry in the army. Apart from the Albanian stradioti, Greek and Italian ones were also deployed in the League of Venice at the Battle of Fornovo (1495).[12] The mercenaries were recruited from the Balkans, mainly Christians but also some Muslims.[13] In 1511, a group of stratioti petitioned for the construction of the Greek community's Eastern Catholic Church in Venice, the San Giorgio dei Greci,[14] and the Scuola dei Greci (Confraternity of the Greeks), in a neighborhood where a Greek community still resides.[15] Impressed by the unorthodox tactics of the stratioti, other European powers quickly began to hire mercenaries from the same region.

In various medieval sources the recruits are mentioned either as Greeks or Albanians. The bulk of stradioti rank and file were of Albanian origin from regions of Greece, but by the middle of the 16th century there is evidence that many of them had been Hellenized and in some occasions even Italianized. Hellenization was possibly underway prior to service abroad, since stradioti of Albanian origin had settled in Greek lands for two generations before their emigration to Italy. Moreover, since many served under Greek commanders and together with the Greek stradioti, this process continued. Another factor in this assimilative process was the stradioti's and their families' active involvement and affiliation with the Greek Orthodox or Uniate Church communities in the places they lived in Italy.[5]

The Kingdom of Naples hired Albanians, Greeks and Serbs into the Royal Macedonian Regiment (Italian: Reggimento Real Macedone), a light infantry unit active in the 18th century.[16] Spain also recruited this unit.[17]

France

France under Louis XII recruited some 2,000 stradioti in 1497, two years after the battle of Fornovo. Among the French they were known as estradiots and argoulets. The term "argoulet" is believed to come either from the Greek city of Argos, where many of argoulets come from (Pappas), or from the arcus (bow) and the arquebuse.[18] For some authors argoulets and estradiots are synonymous but for others there are certain differences between them. G. Daniel, citing M. de Montgommeri, says that argoulets and estradiots have the same armoury except that the former wear a helmet.[19] According to others "estradiots" were Albanian horsemen and "argoulets" were Greeks, while Croatians were called "Cravates".[20]

The argoulets were armed with a sword, a mace (metal club) and a short arquebuse. They continued to exist under Charles IX and are noted at the battle of Dreux (1562). They were disbanded around 1600.[21] The English chronicle writer Edward Hall described the "Stradiotes" at the battle of the Spurs in 1513. They were equipped with short stirrups, small spears, beaver hats, and Turkish swords.[22]

The term "carabins" was also used in France as well as in Spain denoting cavalry and infantry units similar to estradiots and argoulets (Daniel G.)(Bonaparte N.[23]). Units of Carabins seem to exist at least till the early 18th century.[24]

Corps of light infantry mercenaries were periodically reqruited from the Balkans or Italy mainly during the 15th to 17th centuries. In 1587, the Duchy of Lorraine recruited 500 Albanian cavalrymen, while from 1588 to 1591 five Albanian light cavalry captains were also recruited.[25]

Spain

Stratioti were first employed by Spain in their Italian expedition (see Italian Wars). Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba ("Gran Capitan") was sent by King Ferdinand II of Aragon ("the Catholic") to support the kingdom of Naples against the French invasion. In Calabria Gonzalo had two hundred "estradiotes Griegos, elite cavalry".[26]

Units of estradiotes served also in the Guard of King Ferdinand and, along with the "Alabarderos", are considered the beginnings of the Spanish Royal Guard.[27]

England

In 1514, Henry VIII of England, employed units of Albanian and Greek stradioti during the battles with the Kingdom of Scotland.[15][28] In the 1540s, Duke Edward Seymour of Somerset used Albanian stradioti in his campaign against Scotland.[29] An account of the presence of stratioti in Britain is given by Nikandros Noukios of Corfu. In about 1545 Noukios followed as a non-combatant the English invasion of Scotland where the English forces included Greeks from Argos under the leadership of Thomas of Argos whose "Courage, and prudence, and experience of wars" was lauded by the Corfiot traveller.[30][note 1] Thomas was sent by Henry VIII to Boulogne in 1546, as commander of a battalion of 550 Greeks and was injured in the battle.[31] The King expressed his appreciation to Thomas for his leadership in Boulogne and rewarded him with a good sum of money.

Holy Roman Empire

In the middle of the 18th century, Albanian stratioti were employed by Empress Maria Theresa during the War of the Austrian Succession against Prussian and French troops.[32]

Tactics

The stratioti were pioneers of light cavalry tactics during this era. In the early 16th century heavy cavalry in the European armies was principally remodeled after Albanian stradioti of the Venetian army, Hungarian hussars and German mercenary cavalry units (Schwarzreiter).[33] They employed hit-and-run tactics, ambushes, feigned retreats and other complex maneuvers. In some ways, these tactics echoed those of the Ottoman sipahis and akinci. They had some notable successes also against French heavy cavalry during the Italian Wars.[34]

They were known for cutting off the heads of dead or captured enemies, and according to Commines they were paid by their leaders one ducat per head.[35]

Equipment

The stradioti used javelins, as well as swords, maces, crossbows, bows, and daggers. They traditionally dressed in a mixture of Ottoman, Byzantine and European garb: the armor was initially a simple mail hauberk, replaced by heavier armor in later eras. As mercenaries, the stradioti received wages only as long as their military services were needed.[36]

Notable stratioti

- Mercurio Bua

- Krokodeilos Kladas

- Demetrio Reres

- Matthew Spanoudes (or Spadugnino), a stradioti who earned the title of "Count and Knight of the Holy Roman Empire" from Emperor Frederick III[37]

- Palaiologos (also Paleologos) family:

- Graitzas Palaiologos, a leader of the stradioti.[38]

- Manolis Paleologos, Nicolos Paleologos[39]

- Teodoros Paleologos ("capo"), Ioannes (Zuan) Paleologos, Alexandros Paleologos[40]

- Demetrios Laskaris, son of Isaakios, unit commander[41]

- Isaakios Laskaris, killed in the battle of Fornovo (1495) (Sathas)

- Panagiotis Doxaras, horseman by the Venetian army and painter (1662-1729)

- Thomas of Argos, captain of a battalion of 550 Greek stratioti who served in the English army in the era of Henry VIII. Thomas was injured in the Siege of Boulogne (1546) fighting victoriously against a unit of more than 1,000 French (Moustoxydes, 1856).

- Michael Tarchaniota Marullus, Renaissance scholar, poet and humanist

Notes

- ↑ Cramer’s translation of A.Noukios' work stops exactly where the text starts referring to Thomas of Argos. A Greek historian, Andreas Moustoxydes, published the missing part of the original Greek text, based on a manuscript kept in the Ambrosian Library (Milan). After Cramer's asterisks (end of his translation) the text continues as follows:

[Hence, indeed, Thomas also, the general of the Argives from Peloponnesus, with those about him ***] spoke to them so:

“Comrades, as you see we are in the extreme parts of the world, under the service of a King and a nation in the farthest north. And nothing we brought here from our country other than our courage and bravery. Thus, bravely we stand against our enemies, …. Because we are children of the Greeks and we are not afraid of the barbarian flock. …. Therefore, courageous and in order let us march to the enemy, … , and the famous since olden times virtue of the Greeks let us prove with our action.“

(*) Έλληνες in the original Greek text. This incident happened during the Sieges of Boulogne (1544–1546).

References

- ↑ Nicolle & McBride 1988, p. 44.

- ↑ Tardivel 1991, p. 134.

- ↑ Liddell H., Scott R., A Greek-English Lexicon, στρατιώτης (e.g. Herodotus 4,134, Xenophon, Cyrus An. 7, ch. 1, 4 etc.)

- ↑ Trecanni (ed.), Grande Enciclopedia Italiana, "Stradioti": "dal basso greco στρατιώται"; Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici 2005, p. 3: "dal greco stratiòta".

- 1 2 3 4 Pappas (Sam Houston State University).

- ↑ Folengo & Mullaney 2008, p. 491.

- ↑ Nicolle, 1989.

- ↑ B. N. Floria, "Vykhodtsy iz Balkanakh stran na russkoi sluzhbe," Balkanskia issledovaniia. 3. Osloboditel'nye dvizheniia na Balkanakh (Moscow, 1978), pp. 57-63.

- ↑ Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568 by David Nicolle, Angus McBride: "John Comnenus [...] settled Serbs as stratioti around Izmir..."

- ↑ Nicol, Donald M. (1988). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural relations. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 37. "Young men recruited from among Greeks and Albanians. They were known as stradioti from the Greek word for soldier."

- ↑ Nicolle, 2002: p. 16

- ↑ Setton 1976, p. 494; Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 16.

- ↑ Detrez & Plas 2005, p. 134.

- ↑ Detrez & Plas 2005, p. 134, Footnote #24.

- 1 2 English Historical Review 2000, p. 192.

- ↑ Alex N. Dragnich (1994). Serbia's Historical Heritage. East European Monographs. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-88033-244-6.

- ↑ Modern Greek Studies Association (1976). Hellenism and the first Greek war of liberation (1821-1830): continuity and change. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 72.

- ↑ Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue françoise, vol. 1

- ↑ Daniel R.P.G. (1724) Histoire de la milice francoise, et des changemens qui s'y sont ... , Amsterdam, vol. 1, pp. 166-171.

- ↑ Virol M. (2007) Les oisivetes de monsieur de Vauban, edition integrale, Champ Vallon, Seyssel, p. 988, footnote 3.

- ↑ La Grand Encyclopedie, Eole-Fanucci, Paris (undated), vol. 16, article "Argoulet"

- ↑ Hall, Edward, Chronicle (1809), p. 543, 550

- ↑ Bonaparte N. Études sur le passé et l'avenir de l'artillerie, Paris, 1846, vol. 1, p. 161

- ↑ Boyer Abel (1710) The history of the reign of Queen Anne, year the eight, London, p. 86. A list of French captured by the British at the battle of Tasnieres (1709) includes an officer of the "Royal Carabins"

- ↑ Monter 2007, p. 76.

- ↑ Historia del Rey Don Fernando el Catolico: De las empresas y ligas de Italia, book V, p. 3.

- ↑ LA GUARDIA REAL Archived 2010-11-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Higham 1972, p. 171.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Nicander Nucius, The second book of the travels of Nicander Nucius of Corcyra, ed. by Rev. J.A. Cramer, 1841, London, p.90. See also Note 1.

- ↑ Moustoxydes Andreas (1856) Nikandros Noukios, in the periodical Pandora, vol. 7, No. 154, 15 Augh. 1856, p. 222 In Greek language.

Andreas Moustoxydes was a Greek historian and politician. - ↑ Howard 2009, p. 77.

- ↑ Downing 1992, p. 66.

- ↑ Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ DeCommines, Philippe, Lettres et Negotiations, with comments by Kervyn De Lettenhove, ed. 1868, V. Devaux et Cie. Bruxelles, vol. 2, p. 200, 220: "quinze cents estradiotes grecs ou albanais, "vaillans hommes" qui recevaient in ducat par tete d' ennemi qu'ils rapportaient a leurs chefs".

- ↑ Hoerder 2002, p. 63: "Throughout Europe footmen replaced knights, that is, cavalry. They used new weapons and came with regionally varying skills: English archers and crossbowmen, Swiss pikemen, Flemish burgher forces, and, later, Italian gunfighters or exiled Albanian and Greek stradioti on light horse (from Italian strada: street). Mercenaries hired on for pay under "military enterprisers" received wages only as long as work was available."

- ↑ Nicol 1994, p. 104; Nicol 1992, p. 417; Nicol 1968, p. 231.

- ↑ Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 16.

- ↑ Cronaca Cittadina II

- ↑ Medin, Antonio. La Obsidione di Padua del MDIX, ed. Romagnoli. Bologna, 1892.

- ↑ Sathas 1867, p. 97.

Sources

Primary sources

- Bembi, Petri (1551). Historiae Venetae. Venetiis: Apud Aldi Filios,. Available online in Latin language.

- Bembo, Pietro (1780). Storia Veneta. Venice, Italy. In Italian language.

- De Commines, Philip. Memoirs.

first published in 1524.

- Battle of Fornovo: Memoirs, 1856 edition, London, vol. 2, p. 201.

Secondary sources

- Bugh, Glenn Richard (2002). Andrea Gritti and the Greek stradiots of Venice in the early 16th century. 32. Thesaurismata (Bulletin of the Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini di Venezia). pp. 81–94.

- Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (2005). Developing Cultural Identity in the Balkans: Convergence vs Divergence. Peter Lang. ISBN 90-5201-297-0.

- English Historical Review (2000). "Shorter Notice. Greek Emigres in the West, 1400-1520. Jonathan Harris". 115 (460). Oxford Journals: 192–193. doi:10.1093/ehr/115.460.192.

- Downing, Brian M. (1992). The Military Revolution and Political Change: Origins of Democracy and Autocracy in Early Modern Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02475-8.

- Floria, B. N. (1978). "Vykhodtsy iz Balkanakh stran na russkoi sluzhbe". Balkanskia issledovaniia 3, Osloboditel'nye dvizheniia na Balkanakh. Moscow: 57–63.

- Folengo, Teofilo; Mullaney, Ann E. (2008). Baldo, Books 13-15. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03124-1.

- Hammer, Paul E. J. (2003). Elizabeth's Wars: War, Government, and Society in Tudor England, 1544-1604. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-91942-4.

- Higham, Robin D. S. (1972). A Guide to the Sources of British Military History. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7251-1.

- Hoerder, Dirk (2002). Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2834-8.

- Howard, Michael (2009). War in European History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954619-0.

- Monter, E. William (2007). A Bewitched Duchy: Lorraine and its Dukes, 1477-1736. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-01165-5.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42894-7.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1994). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45531-6.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (2002). The Immortal Emperor: The Life and Legend of Constantine Palaiologos, Last Emperor of the Romans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89409-3.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1968). The Byzantine Family of Kantakouzenos (Cantacuzenus) ca. 1100-1460: A Genealogical and Prosopographical Study. Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University.

- Nicolle, David; McBride, Angus (1988). Hungary and the Fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-833-1.

- Nicolle, David; Rothero, Christopher (1989). The Venetian Empire 1200-1670. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-899-4.

- Pappas, Nicholas C. J. "Stradioti: Balkan Mercenaries in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Italy". Sam Houston State University. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- Sathas, Konstantinos (1867). Hellenika Anekdota (Volume 1) (in Greek). Available online

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204-1571): The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (Volume 1). American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

- Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici (2005). "Sul Tutto: Periodico della Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici, No. 3" (PDF).

- Tardivel, Louis (1991). Répertoire des emprunts du français aux langues étrangères (in French). Québec: Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 2-921114-51-8.

- Wright, Diana Gilliland (1999). Bartolomeo Minio: Venetian Administration in 15th-century Nauplion. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America.

Further reading

- Curt Johnson: The French Army of the Early Italian Wars

- Lopez, R. Il principio della guerra veneto-turca nel 1463. "Archivio Veneto", 5 serie, 15 (1934), pp. 47–131.

- Μομφερράτου, Αντ. Γ. Σιγισμούνδος Πανδόλφος Μαλατέστας. Πόλεμος Ενετών και Τούρκων εν Πελοποννήσω κατά 1463-6. Αθήνα, 1914.

- Sathas, K. N. Documents inédits relatifs à l' histoire de la Grèce au Moyen Âge, publiés sous les auspices de la Chambre des députés de Grèce. Tom. VI: Jacomo Barbarigo, Dispacci della guerra di Peloponneso (1465-6), Paris, 1880–90, pp. 1-116.

- Κορρέ Β. Κατερίνα,"Έλληνες στρατιώτες στο Bergamo. Οι πολιτικές προεκτάσεις ενός εκκλησιαστικού ζητήματος", Θησαυρίσματα 28 (2008), 289-336.

- Stathis Birtachas, «La memoria degli stradioti nella letteratura italiana del tardo Rinascimento», in Tempo, spazio e memoria nella letteratura italiana. Omaggio ad Antonio Tabucchi / Χρόνος, τόπος και μνήμη στην ιταλική λογοτεχνία. Τιμή στον Antonio Tabucchi, a cura di Z. Zografidou, Salonicco, Università Aristotele di Salonicco – Aracne – University Studio Press, 2012, pp. 124–142. Online: https://www.academia.edu/2770159/La_memoria_degli_stradioti_nella_letteratura_italiana_del_tardo_Rinascimento

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stratioti. |