Southwest Airlines Flight 1380

.jpg) N772SW, the aircraft involved in the accident photographed in 2013 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | April 17, 2018 |

| Summary | Engine failure, under investigation |

| Site | Over Pennsylvania[1] |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 737-7H4 |

| Operator | Southwest Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | WN1380 |

| ICAO flight No. | SWA1380 |

| Call sign | SOUTHWEST 1380 |

| Registration | N772SW |

| Flight origin |

LaGuardia Airport, New York City, New York |

| Destination |

Dallas Love Field, Dallas, Texas |

| Occupants | 149 |

| Passengers | 144 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Injuries | 8 |

| Survivors | 148 |

|

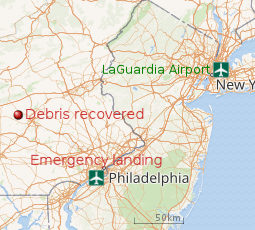

Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 was a Boeing 737-700 that experienced an engine failure after departing from New York–LaGuardia Airport en route to Dallas Love Field on April 17, 2018. Debris from the failed engine damaged the fuselage, causing rapid depressurization of the aircraft after damaging a cabin window. The crew conducted an emergency descent and diverted to Philadelphia International Airport. One passenger was partially ejected from the aircraft and later died. Eight other passengers received minor injuries. The aircraft was substantially damaged.[2] It was the first fatal airline accident involving a U.S. passenger carrier since the crash of Colgan Air Flight 3407 in February 2009.

Background

Flight 1380 was a regularly scheduled passenger flight from New York-LaGuardia Airport to Dallas Love Field.[2] The aircraft was a Boeing 737-7H4[lower-alpha 1] with the registration N772SW, in service with Southwest Airlines since its manufacture in 2000.[3] It was powered by CFM56-7B engines.[2]

Tammie Jo Shults, a former United States Navy pilot, was the captain of the flight;[4] and Darren Ellisor, a former United States Air Force pilot, was the first officer.[5] There were 144 passengers and a total of five crew members on board.[2]

Accident

At 11:03 Eastern Daylight Time, the aircraft was at about flight level 320 (an altitude of approximately 32,000 feet (9,800 m)) and climbing when the left engine failed. As a result most of the engine inlet and parts of the cowling broke off. Fragments from the inlet and cowling struck the wing and fuselage, damaging a passenger window which then failed, causing a rapid depressurization. The flight crew conducted an emergency descent of the aircraft and diverted it to Philadelphia International Airport. One passenger sitting adjacent to the failed window received fatal injuries and eight passengers received minor injuries. The aircraft sustained substantial damage.[2]

The flight crew stated the departure and climb from LaGuardia were normal with no indications of any problems; the first officer was flying and the captain was monitoring. They reported that the aircraft yawed with several cockpit alarms; there was a "gray puff of smoke" and a sudden change in cabin pressure. They donned their oxygen masks, and the first officer began a descent. Flight data recorder (FDR) data showed that the left engine parameters all dropped simultaneously, vibration increased, and, within five seconds, the cabin altitude alert activated. The FDR also indicated that the aircraft rolled left to about 40 degrees before the flight crew was able to counter the roll with control inputs. The flight crew reported that the aircraft exhibited handling difficulties throughout the remainder of the flight. The captain took over flying duties and the first officer began to carry out the emergency checklist procedures. The captain requested a diversion from the air traffic controller; she first requested the nearest airport but quickly decided on Philadelphia. The controller provided vectors to the airport with no delay. The flight crew reported initial communications difficulties because of the loud sounds, distraction, and wearing masks, but, as the aircraft descended, the communications improved. The captain initially was planning on a long final approach to make sure they completed all the checklists, but when they learned of the passenger injuries, she decided to shorten the approach and expedite landing.[2]

Three flight attendants were assigned to the flight, and an additional Southwest Airlines employee was also traveling as a passenger. All four reported that they heard a loud sound and felt a vibration. The oxygen masks automatically deployed in the cabin. The flight attendants retrieved portable oxygen bottles and began moving through the cabin to assist passengers with their masks. As they moved toward the mid-cabin, they found the passenger in row 14 partially out of the window and attempted to pull her inside. They were able to retrieve her with the help of two passengers,[2] and other passengers performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[6] The passenger, later identified as Jennifer Riordan, age 43, was removed from the aircraft alive but died in a local hospital.[7]

Investigation

Initial investigation

The participants in the investigation include the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB),[8] the United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Boeing, Southwest Airlines, GE Aviation, the Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association, the Southwest Airlines Pilots’ Association, the Transport Workers Union of America, and UTC Aerospace Systems.[2] Because the manufacturer of the failed engine – CFM International (CFM) – is a US-French joint venture, the French Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile (Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety; BEA) sent its experts to assist.[9] Technical teams from CFM[10] are assisting with the investigation as well. The full investigation is likely to take 12 to 15 months.[11]

NTSB investigators analyzed a recording of the air traffic radar plots and observed that the radar had shown debris falling from the aircraft, and used wind data to predict where ground searchers could find it.[12] Parts from the engine's nacelle were found in the predicted area at several locations near the town of Bernville, Berks County, Pennsylvania,[1] some 60 miles (100 km; 50 nmi) northwest of Philadelphia.[13][14]

On April 20, 2018, CFM issued Service Bulletin 72-1033 applicable to the CFM56-7B-series engines recommending ultrasonic inspections of all fan blades on engines that have accumulated 20,000 engine cycles and subsequently at intervals not to exceed 3,000 engine cycles.[2]

On April 20, 2018, the FAA issued emergency airworthiness directive (EAD) 2018-09-51[15][16] based on the CFM service bulletin. The EAD required CFM56-7B engine fleet fan blade inspections for engines with 30,000 or greater cycles. The EAD required that within 20 days of issuance that all CFM56-7B engine fan blade configurations to be ultrasonically inspected for cracks per the instructions provided in CFM SB 72-1033, and, if any crack indications were found, the affected fan blade must be removed from service before further flight. This inspection was issued as a one time inspection requirement.[15] On the same day, EASA also issued EAD 2018-0093E[17] (superseding EASA AD 2018-0071) that required the same ultrasonic fan blade inspections to be performed.[2] The engine manufacturer estimated the new directive affected 352 engines in the US and 681 engines worldwide.[15]

On April 23, 2018, Southwest Airlines announced that it was voluntarily going beyond the FAA EAD requirement and performing ultrasonic inspections on all CFM engines in its fleet, including two each on approximately 700 Boeing 737-700 and 737-800 aircraft.[18]

On April 30, 2018, the aircraft involved in the accident was released by the NTSB, and was flown by Southwest Airlines to a service facility performing major services on Boeing aircraft at Paine Field in Everett, Washington for repairs.[19]

On May 2, 2018, the FAA issued a follow up airworthiness directive, AD 2018-09-10,[20] which expanded the inspections on CFM56-7B engines beyond the original EAD 2018-09-51. The new AD required inspections of engines with lower cycles, and introduces repeat inspection requirements as well. Effective with the issuance of this AD, operators are required to perform detailed inspections on each fan blade before the fan blade accumulates 20,000 cycles since new, or within 113 days, whichever occurs later. If cycles since new on a fan blade is unknown, to perform an initial inspection within 113 days from the effective date of this AD. Thereafter, repeat this inspection no later than 3,000 cycles since the last inspection. If any unserviceable parts were found, the affected fan blade must be removed from service before further flight. The FAA estimates this AD affects 3,716 engines installed on aircraft of U.S. registry at an estimated cost of US$8,585 per blade replacement.

On June 7, 2018, the aircraft involved in the accident was flown from a service facility performing major services on Boeing aircraft at Paine Field in Everett, Washington to Southern California Logistics Airport in Victorville, California for storage. It has not been flown since.[21]

On July 24, 2018, the NTSB announced an investigative hearing will be held on Nov. 14, 2018.[22]

Preliminary findings

On May 3, 2018, the NTSB released an investigative update with preliminary findings:[2]

- Initial examination of the aircraft revealed that the majority of the inlet cowl was missing, including the entire outer barrel, the aft bulkhead, and the inner barrel forward of the containment ring. The inlet cowl containment ring was intact but exhibited numerous impact witness marks. Examination of the fan case revealed no through-hole fragment exit penetrations; however, it did exhibit a breach hole that corresponded to one of the fan blade impact marks and fan case tearing.

- The No.13 fan blade had separated at the root; the dovetail remained installed in the fan disk. Examination of the No. 13 fan blade dovetail exhibited features consistent with metal fatigue initiating at the convex side near the leading edge. Two pieces of the fan blade were recovered from within the engine, between the fan blades and the outlet guide vanes. One piece was part of the blade airfoil root that mated with the dovetail that remained in the fan disk; it was about 12 inches (30 cm) spanwise and full width and weighed about 6.825 pounds (3.096 kg). The other piece, identified as another part of the airfoil, measured about 2 inches (10 cm) spanwise, appeared to be full width, was twisted, and weighed about 0.650 pounds (0.295 kg). All the remaining fan blades exhibited a combination of trailing edge airfoil hard body impact damage, trailing edge tears, and missing material. Some also exhibited airfoil leading edge tip curl or distortion. After the general in situ engine inspection was completed, the remaining fan blades were removed from the fan disk and an ultrasonic inspection was performed, with no other cracks found.

- The No. 13 fan blade was examined further at the NTSB Materials Laboratory. The fatigue fracture propagated from multiple origins at the convex side and were centered about 0.568 inches (14.43 mm) aft of the leading edge face of the dovetail and were located 0.610 inches (15.49 mm) outboard of the root end face. The origin area was located outboard of the dovetail contact face coating, and the visual condition of the coating appeared uniform with no evidence of spalls or disbonding. The fatigue region extended up to 0.483 inches (12.27 mm) deep through the thickness of the dovetail and was 2.232 inches (5.669 cm) long at the convex surface. Six crack arrest lines (not including the fatigue boundary) were observed within the fatigue region and striations consistent with low-cycle fatigue crack growth were observed.

- The accident engine's fan blades had accumulated more than 32,000 engine cycles[lower-alpha 2] since new. Maintenance records showed that the fan blades had been periodically lubricated as required, and that they were last overhauled 10,712 engine cycles before the accident. At the time of the last blade overhaul (November 2012), they were inspected using visual and fluorescent penetrant inspections. After an August 27, 2016, accident in Pensacola, Florida, in which a fan blade fractured, eddy current inspections were incorporated into the overhaul process requirements. In the time since the fan blades' overhaul, the blade dovetails had been lubricated six times. At the time each of these fan blade lubrications occurred, the fan blade dovetail was visually inspected as required.

- The remainder of the airframe exhibited significant impact damage to the leading edge of the left wing, left side of the fuselage, and left horizontal stabilizer. A large gouge impact mark, consistent in shape to a recovered portion of fan cowl and latching mechanism, was adjacent to the row 14 window, which was missing. No window-, structural-, or engine material was found inside the cabin.

Reactions

On April 17, 2018, Elaine Chao, the United States Secretary of Transportation, made a statement to "commend the pilots who safely landed the aircraft, and the crew and fellow passengers who provided support and care for the injured, preventing what could have been far worse."[24]

On April 19, 2018, Martha McSally, a member of the United States House of Representatives from Arizona, and former Air Force combat pilot introduced a resolution in Congress commending Shults.[25]

On May 1, 2018, President Donald Trump welcomed the crew members and selected passengers in a ceremony at the Oval Office of the White House, thanking them all for their heroism.[26] Present were Captain Tammie Jo Shults, First Officer Darren Ellisor, Flight Attendant Rachel Fernheimer, Flight Attendant Seanique Mallory, Flight Attendant Kathryn Sandoval; passenger Tim McGinty with his wife Kristin McGinty, passenger Andrew Needum with his wife Stephanie Needum, and passenger Peggy Phillips.[26]

Aftermath

Southwest Airlines gave each passenger $5,000 and a $1,000 voucher for future travel with the airline.[7][27]

Southwest Airlines bookings fell following the accident, resulting in a projected decline in revenue for the airline for the second quarter of 2018.[28]

Lawsuit

Following the accident, Lila Chavez, a passenger on board the flight, filed a lawsuit against Southwest Airlines, claiming that the accident gave her post traumatic stress disorder.[29]

See also

- National Airlines Flight 27, a 1973 accident involving an uncontained engine failure and a passenger being ejected from the aircraft through a window

- British Airways Flight 5390, a 1990 accident in which a crew member was partially ejected from a window in flight

- Delta Air Lines Flight 1288, a 1996 accident involving an uncontained engine failure and two fatalities from pieces of the engine penetrating the aircraft fuselage

- Southwest Airlines Flight 3472, a 2016 accident involving the same airline with an uncontained engine failure with a similar aircraft and engine

Notes

- ↑ The aircraft was a Boeing 737-700 model; Boeing assigns a unique code for each company that buys one of its aircraft, which is applied as an infix to the model number at the time the aircraft is built, hence "737-7H4" designates a 737-700 built for Southwest Airlines (customer code H4).

- ↑ In aviation, an engine cycle generally consists of an engine start, an aircraft takeoff, an aircraft landing and an engine shutdown. Engine starts without the aircraft flying are not counted as cycles.[23]

References

- 1 2 Gamiz Jr., Manuel (April 19, 2018). "Worker who found Southwest plane debris: 'What! How does airplane stuff fall out of the sky'". The Morning Call. Tronc. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "5/3/2018 Investigative Update Accident No: DCA18MA142". ntsb.gov. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "N772SW Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ Lee, Tracy (April 17, 2018). "Who is Tammie Jo Shults? The pilot who reportedly landed Southwest flight safely". Newsweek. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Glowatz, Elana. "Who Is Darren Ellisor? Co-Pilot During Fatal Southwest Flight With Engine Failure Identified". Newsweek.com. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Healy, Jack; Hauser, Christine (April 18, 2018). "Inside Southwest Flight 1380, 20 Minutes of Chaos and Terror". Nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Karimi, Faith. "Southwest gives $5,000 checks to passengers on Flight 1380". CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ "NTSB_Newsroom on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Bureau d'Enquêtes & d'Analyses on Twitter". Twitter (in French). Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "CFM International on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "One dead after Southwest Airlines jet engine 'explosion'". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt. Second media briefing on Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 investigation. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Debris from Southwest plane recovered in Berks County". 6abc.com. WPVI-TV Philadelphia. April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt (April 17, 2018). First media briefing on Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 investigation. YouTube. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "FAA Emergency Airworthiness Directive 2018-09-51" (PDF). www.faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ "FAA Statement on Issuing Airworthiness Directive (AD)". www.faa.gov. April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Emergency Airworthiness Directive AD No.: 2018-0093-E" (PDF). easa.europa.eu. European Aviation Safety Agency. April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Martin, Hugo (April 23, 2018). "Southwest Airlines inspecting virtually its entire fleet of planes following fatal accident". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Sundell, Allison (April 30, 2018). "Southwest jet in fatal explosion in Everett for repairs". KING 5 News. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ↑ "FAA Airworthiness Directive 2018-09-10" (PDF). www.faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ↑ url=https://flightaware.com/live/flight/N772SW

- ↑ "Engine Failure Subject of NTSB Investigative Hearing" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. Jul 24, 2018.

- ↑ Eggeling, Helmuth (Fall 2013). "Flying the Engine – How Are You Counting Engine Cycles?". Flight Levels Online. Twin Commander LLC. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Statement from U.S. Secretary of Transportation Elaine L. Chao on Southwest Airlines Flight 1380". transportation.gov. April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "McSally to Introduce Congressional Resolution to Honor Southwest Pilot Tammie Jo Shults for Her Life-Saving Heroism" (Press release). Congresswoman Martha McSally. April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- 1 2 News, A. B. C. (May 1, 2018). "Trump meets with Southwest Flight 1380 crew, passengers". ABC News. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Southwest Airlines Gives $5,000 to Passengers on Fatal Flight". April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018 – via bloomberg.com.

- ↑ Gilbertson, Dawn (April 26, 2018). "Southwest Airlines: Bookings fell after fatal accident". azcentral.com. The Arizona Republic. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "A Passenger Who Survived the Fatal Southwest Flight Is Now Suing the Airline". Fortune. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southwest Airlines Flight 1380. |