Sook Ching

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Singapore | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history (pre-1819)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

British colonial era (1819–1942)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Japanese Occupation (1942–45)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Post-war period (1945–62)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal self-government (1955–63)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Merger with Malaysia (1963–65) |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Republic of Singapore (1965–present)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Sook Ching (simplified Chinese: 肃清; traditional Chinese: 肅清; pinyin: Sùqīng; Jyutping: suk1 cing1; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Siok-chheng, meaning "purge through cleansing") was a systematic purge of perceived hostile elements among the Chinese in Singapore by the Japanese military during the Japanese occupation of Singapore and Malaya, after the British colony surrendered on 15 February 1942 following the Battle of Singapore. The massacre took place from 18 February to 4 March 1942 at various places in the region. The operation was overseen by the Kempeitai secret police and subsequently extended to include the Chinese population in Malaya. Scholars agree the massacre took place, but Japanese and Singaporean sources disagree about the number of deaths. According to Hirofumi Hayashi, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs "accepted that the Japanese military had carried out mass killings in Singapore ... During negotiations with Singapore, the Japanese government rejected demands for reparations but agreed to make a 'gesture of atonement' by providing funds in other ways." Officially Japan claims that fewer than 5,000 deaths occurred, while Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's first prime minister, said "verifiable numbers would be about 70,000". In 1966 Japan agreed to pay $50 million in compensation, half of which was a grant and the rest as a loan. They did not make an official apology.

The memories of those who lived through that period have been captured at exhibition galleries in the Old Ford Motor Factory at Bukit Timah, the site of the former factory where the British surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February 1942.[1]

The Japanese referred to the Sook Ching as the Kakyō Shukusei (華僑粛清, "purging of Overseas Chinese") or as the Shingapōru Daikenshō (シンガポール大検証, "great inspection of Singapore"). The current Japanese term for the massacre is Shingapōru Kakyō Gyakusatsu Jiken (シンガポール華僑虐殺事件, "Singapore Overseas Chinese Massacre"). Singapore's National Heritage Board uses the term Sook Ching in its publications.[2][3]

Planning of the massacre

According to postwar testimony taken from a war correspondent embedded with the 25th army, Colonel Hishakari Takafumi, an order to kill 50,000 Chinese, 20% of the total, was issued by senior officials on Yamashita's Operations staff, either from Lieutenant Colonel Tsuji Masanobu, Chief of Planning and Operations, or Major Hayashi Tadahiko, Chief of Staff. [4] [5][6]

Hirofumi Hayashi, a professor of politics at a University and the Co-Director of the Center for Research and Documentation on Japan's War Responsibility, writes that the massacre was premeditated, and that "the Chinese in Singapore were regarded as anti-Japanese even before the Japanese military landed". It is also clear from the passage below that the massacre was to be extended to the Chinese in Malaya as well.

The purge was planned before Japanese troops landed in Singapore. The military government section of the 25th Army had already drawn up a plan entitled "Implementation Guideline for Manipulating Overseas Chinese" on or around 28 December 1941.[9] This guideline stated that anyone who failed to obey or co-operate with the occupation authorities should be eliminated. It is clear that the headquarters of the 25th Army had decided on a harsh policy toward the Chinese population of Singapore and Malaya from the beginning of the war. According to Onishi Satoru,[10] the Kempeitai officer in charge of the Jalan Besar screening centre, Kempeitai commander Oishi Masayuki was instructed by the chief of staff, Sōsaku Suzuki, at Keluang, Johor, to prepare for a purge following the capture of Singapore. Although the exact date of this instruction is not known, the Army headquarters was stationed in Keluang from 28 January to 4 February 1942 ...

Clearly, then, the Singapore Massacre was not the conduct of a few evil people, but was consistent with approaches honed and applied in the course of a long period of Japanese aggression against China and subsequently applied to other Asian countries. To sum up the points developed above, the Japanese military, in particular the 25th Army, made use of the purge to remove prospective anti-Japanese elements and to threaten local Chinese and others to swiftly impose military administration.[7]

After the Japanese military occupied Singapore, they were aware that the local Chinese population was loyal to the Republic of China. Some Chinese had been financing the National Revolutionary Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War through a series of fund-raising propagandist events.

Targeted groups

The Japanese military authorities defined the following as "undesirables":[8]

- Activists in the China Relief

- Wealthy philanthropists who had contributed generously to the China Relief Fund, such as modernist architect, Ho Kwong Yew, who designed and built many houses of note in Singapore for the wealthy Chinese community of the time.

- Adherents of Tan Kah Kee, leader of the Nanyang National Salvation Movement

- Hainan people, who were perceived to be communists

- Chinese-born Chinese who came to Malaya after the Second Sino-Japanese War

- Men with tattoos, who were perceived to be triad members

- Chinese who joined the Singapore Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Volunteer Army

- Civil servants and those who were likely to sympathise with the British, such as the Justices of the Peace and members of the legislative council

- People who possessed weapons and were likely to disrupt public security

The massacre

The "screening"

After the fall of Singapore, Masayuki Oishi, commander of No. 2 Field Kempeitai, set up his headquarters in the YMCA Building at Stamford Road as the Kempeitai East District Branch. The Kempeitai prison was in Outram with branches in Stamford Road, Chinatown and the Central Police Station. A residence at the intersection of Smith Street and New Bridge Road formed the Kempeitai West District Branch.

Under Oishi's command were 200 regular Kempeitai officers and another 1000 auxiliaries, who were mostly young and rough peasant soldiers. Singapore was divided into sectors with each sector under the control of an officer. The Japanese set up designated "screening centres" all over Singapore to gather and "screen" Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50.[9][10] Those who were thought to be "anti-Japanese" would be eliminated. Sometimes, women and children were also sent for inspection as well.

The following passage is from an article from the National Heritage Board:

The inspection methods were indiscriminate and non-standardised. Sometimes, hooded informants identified suspected anti-Japanese Chinese; other times, Japanese officers singled out "suspicious" characters at their whim and fancy. Those who survived the inspection walked with "examined" stamped on their faces, arms or clothing; some were issued a certificate. The unfortunate ones were taken to remote places like Changi and Punggol, and unceremoniously killed in batches.[3]

According to the A Country Study: Singapore published by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress:

All Chinese males from ages eighteen to fifty were required to report to registration camps for screening. The Japanese or military police arrested those alleged to be anti-Japanese, meaning those who were singled out by informers or who were teachers, journalists, intellectuals, or even former servants of the British. Some were imprisoned, but most were executed.[11]

The ones who passed the "screening" [9] received a piece of paper bearing the word "examined" or have a square ink mark stamped on their arms or shirts. Those who failed were stamped with triangular marks instead. They were separated from the others and packed into trucks near the centres and sent to the killing sites.

Execution

There were several sites for the killings, the most notable ones being Changi Beach, Punggol Point and Sentosa (or Pulau Belakang Mati).

| Massacre sites: | Description |

|---|---|

| Punggol Point | The Punggol Point Massacre saw about 300 to 400 Chinese shot on 28 February 1942 by the Hojo Kempei firing squad. The victims were some of the 1,000 Chinese men detained by the Japanese after a door-to-door search along Upper Serangoon Road. Several of these had tattoos, a sign that they might be triad members. |

| Changi Beach/Changi Spit Beach | On 20 February 1942, 66 Chinese males were lined up along the edge of the sea and shot by the military police. The beach was the first of the killing sites of the Sook Ching. Victims were from the Bukit Timah/Stevens Road area. |

| Changi Road 8-mile section (ms) | Massacre site found at a plantation area (formerly Samba Ikat village) contained remains of 250 victims from the vicinity. |

| Hougang 8 ms | Six lorry loads of people were reported to have been massacred here. |

| Katong 7 ms | 20 trenches for burying the bodies of victims were dug here. |

| Beach opposite 27 Amber Road | Two lorry loads of people were said to have been massacred here. The site later became a car park. |

| Tanah Merah Beach/Tanah Merah Besar Beach | 242 victims from Jalan Besar were massacred here. The site later became part of the Changi airport runway. |

| Sime Road off Thomson Road | Massacre sites found near a golf course and villages in the vicinity. |

| Katong, East Coast Road | 732 victims from Telok Kurau School. |

| Siglap area | Massacre site near Bedok South Avenue/Bedok South Road (previously known as Jalan Puay Poon). |

| Belakang Mati Beach, off the Sentosa Golf Course | Surrendered British gunners awaiting Japanese internment buried some 300 bullet-ridden corpses washed up on the shore of Sentosa. They were civilians who were transported from the docks at Tanjong Pagar to be killed at sea nearby.[12] |

In a quarterly newsletter, the National Heritage Board published the account of the life story of a survivor named Chia Chew Soo, whose father, uncles, aunts, brothers and sisters were bayoneted one by one by Japanese soldiers in Simpang Village.[13]

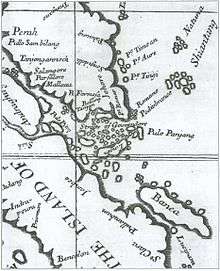

Extension to Malaya

At the behest of Masanobu Tsuji, the Japanese High Command's Chief of Planning and Operations, Sook Ching was extended to the rest of Malaya. However, due to a far wider population distribution across urban centres and vast rural regions, the Chinese population in Malaya was less concentrated and more difficult to survey. Lacking sufficient time and manpower to organise a full "screening", the Japanese opted instead to conduct widespread and indiscriminate massacres of the Chinese population.[14][15] The primary bulk of the killings were conducted between February to March, and were largely concentrated in the southern states of Malaya, closer to Singapore.

Specific incidents were Kota Tinggi, Johore (28 February 1942) – 2,000 killed; Gelang Patah, Johor (4 March) – 300 killed; Benut, Johor (6 March) – number unknown; Johore Baharu, Senai, Kulai, Sedenak, Pulai, Renggam, Kluang, Yong Peng, Batu Pahat, Senggarang, Parit Bakau, and Muar (February–March) – estimated up to 25,000 Chinese were killed in Johor; Tanjung Kling, Malacca (16 March) – 142 killed; Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan (15 March) – 76 killed; Parit Tinggi, Negeri Sembilan (16 March) – more than 100 killed (the entire village);[16] Joo Loong Loong (now known as Titi) (18 March) – 990 killed (the entire village was eliminated by Major Yokokoji Kyomi and his troops);[17] and Penang (April) – several thousand killed by Major Higashigawa Yoshimura. Further massacres were instigated as a result of increased guerilla activity in Malaya, most notably at Sungei Lui, a village of 400 in Jempol District, Negeri Sembilan, which was wiped out on 31 July 1942 by troops under a Corporal Hashimoto.

Death toll

The figures of the death toll vary. Official Japanese statistics show fewer than 5,000 while the Singaporean Chinese community claims the numbers to be around 100,000. Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's first prime minister, said in a Discovery Channel programme that the estimated death toll was "Somewhere between 50,000 to 100,000 young men, Chinese".[10]

In an interview on 6 July 2009 with National Geographic, Lee said:

I was a Chinese male, tall and the Japanese were going for people like me because Singapore had been the centre for the collection of ethnic Chinese donations to Chongqing to fight the Japanese. So they were out to punish us. They slaughtered 70,000 – perhaps as high as 90,000 but verifiable numbers would be about 70,000. But for a stroke of fortune, I would have been one of them.[18]

Hirofumi Hayashi wrote in another paper that the death toll "needs further investigation".

According to the diary of the Singapore garrison commander, Major General Kawamura Saburo, the total number reported to him as killed by the various Kempeitai section commanders on 23 February was five thousand. This was the third day of mop-up operations when executions were mostly finished. It is said in Singapore that the total number killed was forty or fifty thousand; this point needs further investigations.[19]

Having witnessed the brutality of the Japanese, Lee made the following comments:

But they also showed a meanness and viciousness towards their enemies equal to the Huns'. Genghis Khan and his hordes could not have been more merciless. I have no doubts about whether the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary. Without them, hundreds of thousands of civilians in Malaya and Singapore, and millions in Japan itself, would have perished.[20]

Prominent victims

Chinese film pioneer Hou Yao moved to Singapore in 1940 to work for the Shaw brothers. Because Hou had directed and written a number of "national defence" films against the Japanese invasion of China, he was targeted by the Japanese and killed at the beginning of the Sook Ching massacre.[21][22]

Aftermath

In 1947, after the Japanese surrender, British authorities in Singapore held a war crimes trial for the perpetrators of the Sook Ching. Seven Japanese officers: Takuma Nishimura, Saburo Kawamura, Masayuki Oishi, Yoshitaka Yokata, Tomotatsu Jo, Satoru Onishi, and Haruji Hisamatsu, were charged with conducting the massacre. Staff officer Masanobu Tsuji was the mastermind behind the massacre, and personally planned and carried it out, but at the time of the war crimes trials he had not been arrested. As soon as the war ended, Masanobu Tsuji escaped from Thailand to China. The accused seven persons who followed Tsuji's commands were on trial.[6]

During the trial, one major problem was that the Japanese commanders did not pass down any formal written orders for the massacre. Documentation of the screening process or disposal procedures had also been destroyed. Besides, the Japanese military headquarters' order for the speedy execution of the operation, combined with ambiguous instructions from the commanders, led to suspicions being cast on the accused, and it became difficult to accurately establish their culpability.

Saburo Kawamura and Masayuki Oishi received the death penalty while the other five received life sentences, though Takuma Nishimura was later executed following conviction by an Australian military court for his role in the Parit Sulong Massacre in 1951. The court accepted the defence statement of "just following orders" by those put on trial.[8]The condemned were hanged on 26 June 1947. The British authorities allowed only six members of the victims' families to witness the executions of Kawamura and Oishi, despite calls for the hangings to be made public.[23]

The mastermind behind the massacre, Masanobu Tsuji, escaped. Tsuji, later after the trial and the execution, appeared in Japan and became a politician there. Tsuji evaded trial, but later disappeared, presumedly killed in Laos in 1961. Tomoyuki Yamashita, the general from whose headquarters the order seems to have been issued, was put on another trial in the Philippines and executed in 1946. Other staff officers, who planned the massacre, were Shigeharu Asaeda and Sōsaku Suzuki. But, as Shigeharu Asaeda was captured in Russia after the war and Sōsaku Suzuki was killed in action in 1945 before the end of the war, they were not put on trial.

The reminiscences of Saburo Kawamura were published in 1952 (after his death) and, in the book, he expressed his condolences to the victims of Singapore and prayed for the repose of their souls.[6]

Mamoru Shinozaki (February 1908 – 1991), a former Japanese diplomat, has been described as instrumental as key prosecution witness during the Singapore War Crimes Trial between 1946 and 1948.[24] Shinozaki remains a controversial figure, with some blaming him for saying positive things about the accused (despite being a prosecuting witness)[25]; views on him continue to vary, with opinions ranging from calling him the "wire-puller" of the massacre[26] or criticizing him for "self-praise" in his autobiography[27] to calling him a life-saving "Schindler" of Singapore.[28]

When Singapore gained full self-government from the British colonial government in 1959, waves of anti-Japanese sentiments arose within the Chinese community and they demanded reparations and an apology from Japan. The British colonial government had demanded only war reparations for damage caused to British property during the war. The Japanese Foreign Ministry declined Singapore's request for an apology and reparations in 1963, stating that the issue of war reparations with the British had already been settled in the San Francisco Treaty in 1951 and hence with Singapore as well, which was then still a British colony.

Singapore's first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew responded by saying that the British colonial government did not represent the voice of Singaporeans. In September 1963, the Chinese community staged a boycott of Japanese imports (refusing to unload aircraft and ships from Japan), but it lasted only seven days.[29][30]

With Singapore's full independence from Malaysia on 9 August 1965, the Singapore government made another request to Japan for reparations and an apology. On 25 October 1966, Japan agreed to pay S$50 million in compensation, half of which was a grant and the rest as a loan. Japan did not make an official apology.

The remains of the victims of the Sook Ching were unearthed by locals for decades after the massacre. The most recent finding was in late-1997, when a man looking for earthworms to use as fishing bait found a skull, two gold teeth, an arm and a leg. The massacre sites of Sentosa, Changi and Punggol Point were marked as heritage sites by the National Monuments of Singapore in 1995 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of the Japanese occupation.[31]

Legacy

The massacre and its post-war judicial handling by the colonial British administration incensed the Chinese community. The Discovery Channel programme commented about its historic impact on local Chinese: "They felt the Japanese spilling of so much Chinese blood on Singapore soil has given them the moral claim to the island that hasn't existed before the war". Lee Kuan Yew said on the Discovery Channel programme, "It was the catastrophic consequences of the war that changed the mindset, that my generation decided that, 'No ... this doesn't make sense. We should be able to run this [island] as well as the British did, if not better.'"[32] "The Asiatics had looked to them for leadership, and they had failed them."[33]

Germaine Foo-Tan writes in an article carried on the Singapore Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) website:[34]

While the quick defeat of the British in Singapore was a shocking revelation to the local population, and the period of the Japanese Occupation arguably the darkest time for Singapore, these precipitated the development of political consciousness with an urgency not felt before. The British defeat and the fall of what was regarded as an invincible fortress rocked the faith of the local population in the ability of the British to protect them. Coupled with the secret and sudden evacuation of British soldiers, women and children from Penang, there was the uneasy realisation that the colonial masters could not be relied upon to defend the locals. The Japanese slogan "Asia for Asians" awoke many to the realities of colonial rule, that "however kind the masters were, the Asians were still second class in their own country". Slowly, the local population became more aware of the need to have a bigger say in charting their destinies. The post-war years witnessed a political awakening and growing nationalistic feelings among the populace which in turn paved the way for the emergence of political parties and demands for self-rule in the 1950s and 1960s.

See also

References

- ↑ Access to Archives Online – Our Recent Publications Archived 4 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Memories At Old Ford Factory – National Archives of Singapore, National Heritage Board Archived 10 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Sook Ching Centre Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Yuma Totani, Justice in Asia and the Pacific Region, 1945–1952: Allied War Crimes Prosecutions, Cambridge University Press, 2015

- ↑ Kevin Blackburn, ‘The Collective Memory of the Sook Ching Massacre and the Creation of the Civilian War Memorial of Singapore,’ Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 73, No. 2 (279)(2000), pp. 71-90, p.73.

- 1 2 3 Hayashi Hirofumi, 'Massacre of Chinese in Singapore and Its Coverage in Postwar Japan,' in [Akashi Yoji & Yoshimura Mako (eds.),New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, Singapore, National University of Singapore Press, 2008 Chapter 9 .

- ↑ "The Battle of Singapore, the Massacre of Chinese and Understanding of the Issue in Postwar Japan". Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- 1 2 WaiKeng Essay 'Justice Done? Criminal and Moral Responsibility Issues in the Chinese Massacres Trial Singapore, 1947'

Genocide Studies Program. Working Paper No. 18, 2001. Wai Keng Kwok, Branford College/ Yale university - 1 2 Japanese Occupation – Massacre of Chinese Populace Archived 22 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 History Of Singapore 新加坡的歷史 (II) Part 2. YouTube. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+sg0027) Singapore – Shonan: Light of the South

- ↑ National Library Board, Singapore. "Operation Sook Ching". Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Newsletter of the National Heritage Board April – June 2003 p.5 Memories of War – National Archives of Singapore Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lords of the Rim by Sterling Seagrave

- ↑ Southeast Asian culture and heritage in a globalising world: diverging identities in a dynamic region: heritage, culture, and identity eds. Brian J. Shaw, Giok Ling Ooi. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Chapter 6 "Nation-Building, Identity and War Commenmoration Spaces in Malaysia and Singapore", article by Kevin Blackburn, pp.93–111

- ↑ Jap General to face a firing squad, The Straits Times, 14 October 1947, Page 1

- ↑ 990 killings alleged, The Straits Times, 3 January 1948, Page 8

- ↑ "TRANSCRIPT OF MINISTER MENTOR LEE KUAN YEW'S INTERVIEW WITH MARK JACOBSON FROM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ON 6 JULY 2009 (FOR NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE JAN 2010 EDITION)". 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Japanese Treatment of Chinese Prisoners, 1931–1945, Hayashi Hirofumi Archived 11 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lee Kuan Yew. The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore: Times, 1998. [59–60]

- ↑ Zhang, Yingjin (2012). A Companion to Chinese Cinema. John Wiley & Sons. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4443-3029-8.

- ↑ 早期香港电影──国防电影与侯曜 [Early Hong Kong cinema — National Defence Film and Hou Yao]. Ta Kung Pao (in Chinese). 13 February 2014.

- ↑ Sook-Ching (essay) Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Also found in the book "Lords of the Rim", by Sterling Seagrove

- ↑ Tan Sai Siong (27 June 1997). "Japanese official saved many from wartime pogrom". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Nanyang Siang Pau 3 April 1947, Page 5

- ↑ Nanyang Siang Pau 6 April 1947, Page 3

- ↑ Tanaka 1976, p. 237.

- ↑ 'Japanese saviour, the Schindler of S'pore', The Straits Times, 12 September 2005, page.5.

- ↑ Singapore airport workers join in the big boycott Straits Times 25 September 1963 Pg 1

- ↑ "'Blood debt': Now Malaya". Straits Times. 25 September 1963. p. 14. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Singapore's Slaughter beach Archived 20 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (First published in The New Paper, 10 February 1998)

- ↑ History Of Singapore 新加坡的歷史 (II) Part 3. YouTube. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Lee Kuan Yew. The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore: Times, 1998

- ↑ "MINDEF - Page Not Found". Retrieved 10 May 2015.

Further reading

- Akashi, Yoji. "Japanese policy towards the Malayan Chinese, 1941–1945". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 1, 2 (September 1970): 61–89.

- Blackburn, Kevin. "The Collective Memory of the Sook Ching Massacre and the Creation of the Civilian War Memorial of Singapore". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 73, 2 (December 2000), 71–90.

- Blackburn, Kevin. "Nation-Building, Identity And War Commenmoration Spaces in Malaysia And Singapore", Southeast Asian culture and heritage in a globalising world: diverging identities in a dynamic region Heritage, culture, and identity eds. Brian J. Shaw, Giok Ling Ooi. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Chapter 6 pp. 93–111.

- Kang, Jew Koon. "Chinese in Singapore during the Japanese occupation, 1942–1945." Academic exercise – Dept. of History, National University of Singapore, 1981.

- Seagrove, Sterling. Lords of the Rim

- Turnbull, C. M. A History of Singapore: 1819–1988. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1989, Chapter 5.

- National Heritage Board (2002), Singapore's 100 Historic Places, National Heritage Board and Archipelago Press, ISBN 981-4068-23-3

- Singapore – A Pictorial History

- Shinozaki, Mamoru (1982). Syonan—My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Singapore: Times Books International. ISBN 981-204-360-8.

External links

| Library resources about Sook Ching |

- Discovery Channel programme, History of Singapore History Of Singapore 新加坡的歷史 (II) Part 2 History Of Singapore 新加坡的歷史 (II) Part 3