Soho Square

Soho Square is a garden square in Soho, London which has been de facto since 1954 a public park leased to the council at its centre. It was originally called King Square after Charles II. Its statue of Charles II has stood since the square's 1681 founding (one year after the restoration of the monarchy) except between 1875 and 1938; it is today well-weathered. By the time of the drawing of a keynote map of London in 1746 the newer name for the square had gained sway. During the summer, Soho Square hosts open-air free concerts.

At its centre is a listed mock "market cross" building completed in 1926 to hide the above-ground features of a contemporary electricity substation; small, octagonal, with Tudorbethan timber framing. During the statue's absence arranged by resident business Crosse & Blackwell it was privately displayed at Grim's Dyke, a country house where it was kept by painter Frederick Goodall then dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator W. S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan fame.

Initial residents were relatively significant landowners and merchants. Some of the use remains residential. From the 1820s to 1860s at least eleven artists who qualified for major exhibitions are recorded as resident aside from permanent residents, some of whom were more accomplished artists, who paid the rates; by the end of that century charities, music, art and other creative design businesses had taken several premises along the square. A legacy of creative design and philanthropic occupants lingers including the British Board of Film Classification, 20th Century Fox, Dolby Europe Ltd, Tiger Aspect Productions, Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church which provides many social outreach projects to local homeless and addicts, the French Protestant Church of London and the House of St Barnabas a members' club since 2013 which fundraises and hosts events and exhibitions for homeless-linked good causes.

History

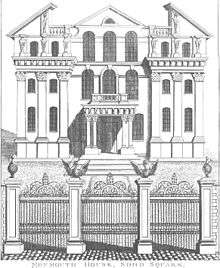

Built in the late 1670s, Soho Square was in its early years one of the most fashionable places to live in London. It was originally called King's Square, for King Charles II. The statue of Charles II was carved by Danish sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber during the King's reign in 1681 and made the centrepiece of the Square; since it has returned it has not been in the centre.[1] The development lease to convert the immediately surrounding fields, for 53 1⁄4 years, was granted in 1677 to Richard Frith, citizen (elector of the Corporation of London) and bricklayer.[2] Ratebooks (of the vestry) continued to call the square King Square until the first decade of the 19th century, however John Rocque's Map of London, 1746 and Richard Horwood's in 1792–9 mark it as Soho Square.[2]

By the early 19th century, the statue, fountain and attendant figures was described as 'in a most wretched mutilated state; and the inscriptions on the base of the pedestal quite illegible'.[1] In 1875, it was removed during alterations in the square by Thomas Blackwell, of Crosse & Blackwell, the condiment firm (who had premises at 20-21 Soho Square from the late 1830s until the early 1920s), who gave it for safekeeping to his friend, artist Frederick Goodall, with the intention that it might be restored.[1] Goodall placed the statue on an island in his lake at Grim's Dyke, where it remained when dramatist W. S. Gilbert purchased the property in 1890, and there it stayed after Gilbert's death in 1911. In her will, Lady Gilbert directed that the statue be returned, and it was restored to Soho Square in 1938.[3]

William Thomas Beckford was born on 29 September 1760 in his family's London home at 22 Soho Square.

In the 1770s, the naturalist Joseph Banks who had circumvented the globe with James Cook, moved into 32 Soho Square in the south-west corner of the square. In 1778, Banks was elected president of the Royal Society and his home became a kind of scientific salon hosting scientists visiting from around the world. His library and herbarium containing many plants gathered during his travels were open to the general public.

Between 1778 and 1801 the Square was home to the infamous White House brothel at the Manor House, 21 Soho Square.[4] In 1852 the Hospital for Women, begun nine years before at Red Lion Square, moved to 30 Soho Square to accommodate 20 more beds. Twelve years later it bought 2 Frith Street; the old site was remodelled in 1908. It moved and merged in 1989 into the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Obstetric Hospital, Euston Road.[5] Eleven artists whose addresses are given as being in Soho Square in exhibition catalogues, whose names do not appear in the vestry ratebooks, are listed by the 1966 Survey of London by historian F H W Sheppard.[2]

A common for commercial/high demand areas sequence of house rebuilding and renovation which had begun in the 1730s, when many of the houses built in the 1670s and 1680s were becoming dilapidated and old fashioned, continued for the next one and a half centuries. After the 1880s the rate of change was considerably faster. Between 1880 and 1914, 11 of the 38 old houses in the square were rebuilt or considerably altered. The majority of the new buildings provided office accommodation only and the residential, mercantile and manufacturing elements in the square declined. However, three of the eleven houses were demolished to make way for church buildings.[2]

Two of the original houses, nos. 10 and 15, still stand. At nos. 8 and 9 is the French Protestant Church of London, built in 1891–3. Fauconberg House was on the north side of the square until its demolition in 1924.[6]

A 200-person air raid shelter was built under the park during World War II, one of dozens in central London. In 2015 Westminster Council announced plans to put it up for sale.[7] In April 1951 the residents' Soho Square Garden Committee leased the garden to the Westminster City Council for 21 years; the garden was not restored and opened to the public until April 1954. New iron railings and gates were provided in 1959 by the Soho Square Garden Committee with the assistance of Westminster City Council.[1]

Residents

In 1862 the charity House of St Barnabas moved around the corner from Rose Street to its present base, 1 Greek Street.[2]

Wilfrid Voynich had his antiquarian bookshop at no. 1 Soho Square from 1902. The publisher Rupert Hart-Davis was at no. 36 from about 1947.

Number 22 was home to British Movietone[8] and Kay (West End) Film Laboratories,[9] having been re-built to its current form between 1913 and 1914.[10]

For almost 40 years from 1955, Soho Square housed the official headquarters of animator Richard Williams.

Present day

Soho Square is home to several media organisations, including the British Board of Film Classification, 20th Century Fox, Bare Escentuals, Deluxe Entertainment Services Group, Dolby Europe Ltd, Fin London, Paul McCartney's MPL Communications, Tiger Aspect Productions, Wasserman Media Group and See Tickets. Past businesses include Sony Music; the linked record label Sony Soho Square is renamed S2 Records.

The Football Association was headquartered at No 25 from October 2000 until 2009.

The square is home to St Patrick's Church, a large Roman Catholic parish church partially on the site of Carlisle House with extensive catacombs that spread deep under the Square and further afield.

Six streets run off the square, counted clockwise from the north

- Soho Street

- Sutton Row

- Greek Street

- Batemans Buildings

- Frith Street

- Carlisle Street.

At the square's centre is a black-and-white, half-timbered, rustic gardener's hut with a steep hipped roof, a squat upper storey which overhangs (jettying), supported by timber columns. Its details use "Tudorbethan" style, built to appear as an octagonal market cross building. It was built in 1926 incorporating 17th or 18th century beams to hide the above-ground features of a contemporary electricity substation.[11][12]

Cultural references

In the book A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Soho Square is where Lucie and her father, Doctor Manette, reside. It is believed that their house is modelled on the House of St Barnabas which Dickens used to visit, and it is for this reason that the street running behind the House from Greek Street is called Manette Street (it was formerly Rose Street).

In the song "Why Can't The English?" from the musical My Fair Lady, Professor Henry Higgins laments, "Hear them down in Soho Square/Dropping H's everywhere."

In the novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke, the eponymous Jonathan Strange and his wife Arabella maintain a home in Soho Square as their residence in London.[13]

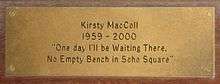

The Soho Square garden contains a bench that commemorates the singer Kirsty MacColl, who wrote the song "Soho Square" for her album Titanic Days. After her death in 2000, fans bought a memorial bench in her honour, inscribing the lyrics: "One day I'll be waiting there / No empty bench in Soho Square".[14]

The Lindisfarne album Elvis Lives On the Moon also includes a song named "Soho Square".[15]

Nearby places (not adjoining)

- Tottenham Court Road tube station

- Oxford Street, to the North

- Charing Cross Road, to the East

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "Soho Square Area: Portland Estate: Soho Square Garden" in Survey of London volumes 33 and 34 (1966) St Anne Soho, pp. 51–53. Date accessed: 12 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sheppard, F. H. W (1966). Survey of London XXXIII Parish of St Anne Soho - Soho Square Area: Portland Estate: Introduction. 2 Gower Street, London: The Athlone Press University of London. p. 89.

- ↑ Photo of the statue Archived 30 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ During, Simon (2004). Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic. Harvard University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-674-01371-1.

... the famous magic brothel, the White House at Soho Square, in which commercial sex was enhanced by dark, baroque special-effects and natural magic devices

- ↑ Christopher Hibbert Ben Weinreb; John & Julia Keay (9 May 2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition). Pan Macmillan. pp. 287–. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

- ↑ Christopher Hibbert Ben Weinreb; John & Julia Keay (9 May 2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition). Pan Macmillan. pp. 287–. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

- ↑ "Bomb shelter under Soho Square could be London's next top restaurant venue, London Evening Standard, 2015

- ↑ Terry Gallacher. "Movietone News, the first days". Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Terry Gallacher. "British Movietonews – the process from idea to screen". Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ "British History Online: No. 22 Soho Square". University of London & History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "Central timber framed arbour/tool shed (1249910)". National Heritage List for England.

- ↑ http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/housecentersohosquare.html

- ↑ http://hurtfew.wikispaces.com/Jonathan+Strange

- ↑ "Bench in Soho Square". Kirsty MacColl. 2001-08-12. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ http://www.lindisfarne.co.uk/discography/elvis-lives-on-the-moon.htm

External links

- Pictures of Soho Square