Smokey Bear

| Smokey Bear | |

|---|---|

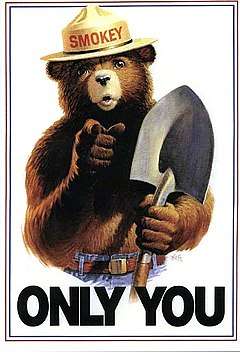

Smokey Bear in a poster based on the "Uncle Sam/Lord Kitchener" poster | |

| First appearance | 1944 |

| Created by | Advertising Council |

| Born |

Spring, 1950 Capitan, New Mexico |

| Information | |

| Species | American black bear |

| Gender | Male |

Smokey Bear is an American advertising icon created by the U.S. Forest Service with artist Albert Staehle,[1][2] possibly in collaboration with writer and art critic Harold Rosenberg.[3] In the longest-running public service advertising campaign in United States history, the Ad Council, the United States Forest Service (USFS), and the National Association of State Foresters (NASF) employ Smokey Bear to educate the public about the dangers of unplanned human-caused wildfires.[4][5]

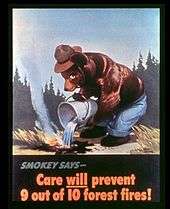

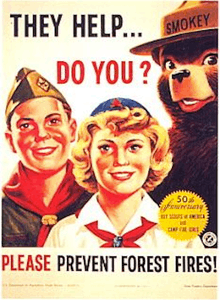

A campaign featuring Smokey and the slogan "Smokey Says – Care Will Prevent 9 out of 10 Forest Fires" began in 1944. His later slogan, "Remember... Only YOU Can Prevent Forest Fires" was created in 1947 and was associated with Smokey Bear for more than five decades.[6][7] In April 2001, the message was officially updated to "Only You Can Prevent Wildfires."[6] in response to a massive outbreak of wildfires in natural areas other than forests (such as grasslands), and to clarify that Smokey is promoting the prevention of unplanned outdoor fire versus prescribed fires.[8][4] According to the Ad Council, 80% of outdoor recreationists correctly identified Smokey Bear's image and 8 in 10 recognized the campaign PSAs.[9]

In 1952, the songwriters Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins had a successful song named "Smokey the Bear" which was performed by Eddy Arnold.[10] The pair said "the" was added to Smokey's name to keep the song's rhythm.[11] During the 1950s, that variant of the name became widespread both in popular speech and in print, including at least one standard encyclopedia, though Smokey Bear's name never officially changed.[12] A 1955 book in the Little Golden Books series was called Smokey the Bear and he calls himself by this name in the book. It depicted him as an orphaned cub rescued in the aftermath of a forest fire, which loosely follows Smokey Bear's true story. From the beginning, his name was intentionally spelled differently from the adjective "smoky".

Smokey Bear's name and image are protected by U.S. federal law, the Smokey Bear Act of 1952 (16 U.S.C. 580 (p-2); 18 U.S.C. 711).[13][14][15]

Campaign beginnings

Although the U.S. Forest Service fought wildfires long before World War II, the war brought a new importance and urgency to the effort. At the time, most able-bodied men were already serving in the armed forces and none could be spared to fight forest fires. The Forest Service began using colorful posters to educate Americans about the dangers of forest fires in the hope that local communities, with the most accurate information, could prevent them from starting in the first place.[7][16]

On August 13, 1942, Disney's fifth full-length animated motion picture Bambi premiered in New York City. Soon after, Walt Disney allowed his characters to appear in fire prevention public service campaigns. However, Bambi was only loaned to the government for a year, so a new symbol was needed.[7] After much discussion, a bear was chosen.[17] His name was inspired by "Smokey" Joe Martin, a New York City Fire Department hero who suffered burns and blindness during a bold 1922 rescue.[18]

Smokey's debut poster was released on August 9, 1944, which is considered the character's birthday.[2][19][20] Overseen by the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Campaign (CFFP), the first poster was illustrated by Albert Staehle. In it Smokey was depicted wearing jeans and a campaign hat,[6][21] pouring a bucket of water on a campfire. The message underneath reads, "Smokey says – Care will prevent 9 out of 10 forest fires!" Knickerbocker Bears gained the license to produce Smokey Bear dolls in 1944.[22] Also in 1949, Forest Service worker Rudy Wendelin became the full-time campaign artist and he was considered Smokey Bear's "manager" until Wendelin retired in 1973.[2]

In addition, during World War II, the Empire of Japan considered wildfires as a possible weapon. During the spring of 1942, Japanese submarines surfaced near the coast of Santa Barbara, California, and fired shells that exploded on an oil field, very close to the Los Padres National Forest. U.S. planners hoped that if Americans knew how wildfires would harm the war effort, they would work with the Forest Service to eliminate the threat.[7][16] The Japanese military renewed their wildfire strategy late in the war: from November 1944 to April 1945, launching some 9,000 fire balloons into the jet stream, with an estimated 11% reaching the U.S.[23] In the end the balloon bombs caused a total of six fatalities: five school children and their teacher, Elsie Mitchell, who were killed by one of the bombs near Bly, Oregon, on May 5, 1945.[24] A memorial was erected at what today is called the Mitchell Recreation Area.

In 1947, the slogan associated with Smokey Bear for more than five decades was finally coined: "Remember ... only YOU can prevent forest fires."[25] In 2001, it was officially amended to replace "forest fires" with "wildfires", as a reminder that other areas (such as grasslands) are also in danger of burning.[26]

Living symbol

The living symbol of Smokey Bear was a five-pound, three month old American black bear cub who was found in the spring of 1950 after the Capitan Gap fire, a wildfire that burned in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico.[27][28][11] Smokey had climbed a tree to escape the blaze, but his paws and hind legs had been burned. Local crews who had come from New Mexico and Texas to fight the blaze removed the cub from the tree.[11]

At first he was called Hotfoot Teddy, but he was later renamed Smokey, after the icon. New Mexico Department of Game and Fish Ranger Ray Bell heard about the cub and took him to Santa Fe, where he, his wife Ruth, and their children Don and Judy cared for the little bear with the help of local veterinarian Dr Edwin J. Smith.[29] The story was picked up by the national news services and Smokey became a celebrity. Many people wrote and called asking about the cub's recovery. The state game warden wrote to the chief of the Forest Service, offering to present the cub to the agency as long as the cub would be dedicated to a conservation and wildfire prevention publicity program. According to the New York Times obituary for Homer C. Pickens, then assistant director of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, he kept the cub on his property for a while, as Pickens would be flying with the bear to D.C.[30][11] Soon after, Smokey was flown in a Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser airplane to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.[11] A special room was prepared for him at the St. Louis zoo for an overnight fuel stop during the trip, and when he arrived at the National Zoo, several hundred spectators, including members of the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, photographers, and media, were there to welcome him.[31]

Smokey Bear lived at the National Zoo for 26 years. During that time he received millions of visitors as well as so many letters addressed to him (more than 13,000 a week) that in 1964 the United States Postal Service gave him his own ZIP code (20252).[27][32][31] He developed a love for peanut butter sandwiches, in addition to his daily diet of bluefish and trout.[31]

Upon his death on November 9, 1976,[27] Smokey's remains were returned by the government to Capitan, New Mexico, and buried at what is now the Smokey Bear Historical Park,[33] operated by New Mexico State Forestry. This facility is now a wildfire and Smokey interpretive center. In the garden adjacent to the interpretive center is the bear's grave.[11][34] The plaque at his grave reads, "This is the resting place of the first living Smokey Bear ... the living symbol of wildfire prevention and wildlife conservation."[35]

The Washington Post ran a semi-humorous obituary for Smokey, labeled "Bear", calling him a transplanted New Mexico native who had resided for many years in Washington, D.C., with many years of government service. It also mentioned his family, including his wife, Goldie Bear, and "adopted son" Little Smokey. The obituary noted that Smokey and Goldie were not blood-relatives, despite the fact that they shared the same "last name" of "Bear".[36] The Wall Street Journal included an obituary for Smokey Bear on the front page of the paper, on November 11, 1976,[31] and so many newspapers included articles and obituaries that the National Zoo archives include four complete scrapbooks devoted to them (Series 12, boxes 66-67).[37]

Smokey Bear II

In 1962, Smokey was paired with a female bear, "Goldie Bear", with the hope that perhaps Smokey's descendants would take over the Smokey Bear title.[35] In 1971, when the pair still had not produced any young, the zoo added "Little Smokey", another orphaned bear cub from the Lincoln Forest, to their cage—announcing that the pair had "adopted" this cub.

On May 2, 1975, Smokey Bear officially "retired" from his role as living icon, and the title, "Smokey Bear II", was bestowed upon Little Smokey in an official ceremony.[31] Little Smokey died August 11, 1990.[11][35]

Smokey's Mission: Wildfire Prevention

It is always fire season somewhere in the United States and every region of the country can experience unplanned wildfires. Nearly nine out of every 10 wildfires in the United States are human-caused, which underscores a main part of Smokey Bear’s message: most of our wildfires can be prevented.[38]

In recent years, Smokey Bear has expanded his digital presence, cultivating robust communities to communicate his wildfire prevention messaging. He provides education and tips on his website, SmokeyBear.com, and social media channels (Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram). Some include:

Campfire Safety: Including how to pick a campfire spot, how to prepare your campfire pit, how to build your campfire and how to maintain and extinguish your campfire.[39]

Equipment Use and Maintenance: Proper use and maintenance of outdoor equipment and vehicles can help prevent sparks that can cause a wildfire. Smokey shares lawn care and vehicle safety tips, as well as how to prepare your home for wildfire.[40]

Backyard Debris Burning: Get information on the proper conditions for burning, what (and what not) to burn, clearance tips, preparing your pile, and other at-home safety tips. To learn whether there are burn restrictions in place near you, check local ordinances.[41]

Popularity

The character became a notable part of American popular culture in the 1950s. He appeared on radio programs, in comic strips, and in cartoons.

In 1952, after Smokey Bear attracted considerable commercial interest, the Smokey Bear Act, an act of Congress, was passed to remove the character from the public domain and place it under the control of the Secretary of Agriculture. The act provided for the use of Smokey's royalties for continued education on the subject of forest wildfire prevention.

A Smokey Bear doll was produced by Ideal Toys beginning in 1952; the doll included a mail-in card for children to become Junior forest rangers. Children could also apply by writing the U.S. Forest Service or Smokey Bear at his zip code.[42][43][11] Within three years half a million children had applied.

In 1955, the first children's book was published, followed by many sequels and coloring books. Soon thousands of dolls, toys, and other collectibles were on the market.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Ad Council sponsored radio advertisements, featuring Smokey Bear "in conversation" with prominent American celebrities such as Bing Crosby, Art Linkletter, Dinah Shore, and Roy Rogers.[44][45][46]

Smokey's name and image are used for the Smokey Bear Awards, which are awarded by the U.S. Forest Service, the National Association of State Foresters (NASF), and the Ad Council, to "recognize outstanding service in the prevention of human-caused wildfires and to increase public recognition and awareness of the need for continuing fire prevention efforts." [47][48]

The Beach Boys bring a reminder of Smokey the Bear on their 1964 album "All Summer Long" in the song "Drive-In" in the lines "If you say you watch the movie you're a couple of liars and 'Remember only you can prevent forest fires'".

Though Smokey was originally drawn wearing the campaign hat of the U.S. Forest Service, the hat itself later became famous by association with the Smokey cartoon character. As such, it is sometimes today called a "Smokey Bear" hat by both the military service branches and state police who still employ it.[49]

Legacy

For Smokey’s 40th anniversary in 1984, he was honored with a U.S. postage stamp that pictured a cub hanging onto a burned tree. It was illustrated by Rudy Wendelin.[50] The commercial for his 50th anniversary portrayed woodland animals about to have a surprise birthday party for Smokey, with a cake with candles. When Smokey comes blindfolded, he smells smoke, not realizing it is birthday candles for his birthday. He uses his shovel to destroy the cake. When he takes off his blindfold, he sees that it was a birthday cake for him and apologizes.[51] That same year, a poster of the bear with a cake full of extinguished candles was issued. It reads, 'Make Smokey's Birthday Wish Come True.'[52]

In 2004, Smokey's 60th anniversary was celebrated in several ways, including a Senate resolution designating August 9, 2004, as "Smokey Bear 60th Anniversary", calling upon the President to issue a proclamation "calling upon the people of the United States to observe the day with appropriate ceremonies and activities." [53]

According to Richard Earle, author of The Art of Cause Marketing, the Smokey Bear campaign is among the most powerful and enduring of all public service advertising: "Smokey is simple, strong, straightforward. He's a denizen of those woods you're visiting, and he cares about preserving them. Anyone who grew up watching Bambi realizes how terrifying a forest fire can be. But Smokey wouldn't run away. Smokey's strong. He'll stay and fight the fire if necessary, but he'd rather have you douse it and cover it up so he doesn't have to."[54]

On the anniversary of finding Smokey Bear in the Capitan Gap fire, Marianne Gould from the Smokey Bear Ranger District, Eddie Tudor from the Smokey Bear Museum and Neal Jones from the local Ruidoso, New Mexico radio station created "Smokey Bear Days" starting in 2004.[55] The event celebrates the fire prevention message from the Smokey Bear campaign as well as wilderness environment conservation with music concerts, chainsaw carving contests, a firefighter's "muster" competition, food, vendors and a parade. The "Smokey Bear Days" celebration is held in Smokey's hometown of Capitan, New Mexico the first weekend of May every year.[56]

In 2008 through 2011, new public service announcements (PSAs) featuring Smokey rendered in CGI were released.[57] In 2010, the PSAs encouraged young adults to “Get Your Smokey On” – that is, to become like Smokey and speak up appropriately when others are acting carelessly.[58] In 2011, the campaign launched its first mobile application, or app, to provide critical information about wildfire prevention, including a step-by-step guide to safely building and extinguishing campfires, as well as a map of current wildfires across America.[59]

In 2012, NASA, the U.S. Forest Service, the Texas Forest Service, and Smokey Bear teamed up to celebrate Smokey's 68th birthday at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston. The popular mascot toured the center and recorded a promotional announcement for NASA Television. NASA astronaut Joe Acaba and the Expedition 31 crew chose a plush Smokey doll to be the team's launch mascot, celebrating their trip to the International Space Station. During his tour about 250 miles above Earth, Smokey turned 68 years old.[60]

In 2014, the campaign celebrated Smokey’s 70th birthday, with new birthday-themed television, radio, print, outdoor, and digital PSAs that continued the 2013 campaign “Smokey Bear Hug.” The campaign depicted Smokey rewarding his followers with a hug, in acknowledgement of using the proper actions to prevent wildfires. In return, outdoor–loving individuals across the nation were shown reciprocating with a birthday bear hug in honor of his 70 years of service. Audiences were encouraged to join in by posting their own #SmokeyBearHug online. The campaign also did a partnership with Disney’s Planes that same year.[61]

In 2016, the campaign launched a new series of PSAs that aimed to increase awareness about less commonly known ways that wildfires can start. The new “Rise from the Ashes” campaign featured art by Bill Fink, who used wildfire ashes as an artistic medium to illustrate the devastation caused by wildfires and highlight less obvious wildfire causes.[62]

In 2017, the campaign launched new socially-optimized videos and artwork inspired by beloved Smokey Bear posters to continue to raise awareness of lesser known wildfire starts. The new artwork was created by Brian Edward Miller, Evan Hecox, Janna Mattia, and Victoria Ying, portraying Smokey Bear in each of their unique styles.[63]

Voices

Washington, D.C., radio station WMAL personality Jackson Weaver served as the primary voice representing Smokey until Weaver's death in October 1992.[64] In June 2008, the Forest Service launched a new series of public service announcements voiced by actor Sam Elliott, simultaneously giving Smokey a new visual design intended to appeal to young adults.[65] Patrick Warburton provides the voice of an anonymous park ranger.[66]

Adaptations

Smokey Bear—and parodies of the character—have been appearing in animation for more than fifty years. In 1956, he made a cameo appearance in the Walt Disney short film In the Bag with a voice provided by Jackson Weaver.[67]

Rankin/Bass Productions, in cooperation with Tadahito Mochinaga's MOM Production in Japan, produced an "Animagic" stop motion animated television special, called The Ballad of Smokey the Bear, narrated by James Cagney.[68] It aired on Thanksgiving Day, November 24, 1966 as part of the General Electric Fantasy Hour on NBC.[69] This same day, a Smokey Bear balloon was featured in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, so it was advertised as "Thanksgiving is Smokey Bear Day on NBC TV." [69] During the 1969–1970 television season, Rankin/Bass also produced a weekly Saturday Morning cartoon series for ABC, called The Smokey Bear Show.[70] This series is animated by Toei Animation in Japan.

Despite his real name being Smokey Bear, the name "Smokey the Bear" has been perpetuated in popular culture. Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins's song "Smokey the Bear" has been covered by the group Canned Heat, among others. The track is on their CD The Boogie House Tapes 1969-1999.

The online battle royale game Fortnite: Battle Royale parodies Smokey and his motto in a loading screen featuring Cuddle Team Leader, a woman dressed in a teddy bear costume replacing Smokey and doing his signature finger-pointing pose. Below her is the message "Only YOU can prevent V-Buck scams", warning players not to risk security compromises by attempting to obtain free virtual currency offered by hackers as bait.

Fire ecology

The Smokey Bear campaign has been criticized by wildfire policy experts in cases where decades of fire suppression and the indigenous fire ecology were not taken into consideration, contributing to unnaturally dense forests with too many dead standing and downed trees, brush, and shrubs often referred to as "fuel".[71][72] Periodic low-intensity wildfires are an integral component of certain ecosystems that evolved to depend on natural fires for vitality, rejuvenation, and regeneration. Examples are chaparral and closed-cone pine forest habitats, which need fire for cones to open and seeds to sprout. Wildfires also play a role in the preservation of pine barrens, which are well adapted to small ground fires and rely on periodic fires to remove competing species.

When a brushland, woodland, or forested area is not affected by fire for a long period, large quantities of flammable leaves, branches and other organic matter tend to accumulate on the forest floor and above in brush thickets. When a forest fire eventually does occur, the increased fuel creates a crown fire, which destroys all vegetation and affects surface soil chemistry. Frequent and small 'natural' ground fires prevent the accumulation of fuel and allow large, slow-growing vegetation (e.g. trees) to survive.

Although the goal of reducing human-caused wildfires has never changed, the tagline of the Smokey Bear campaign was adjusted in the 2000s, from "Only you can prevent forest fires" to "Only you can prevent wildfires". The main reason was to accurately expand the category beyond just forests to include all wildlands, including grasslands. Another reason was to respond to the criticism, and to distinguish 'bad' intentional or accidental wildfires from the needs of sustainable forests via natural 'good' fire ecology.[71]

SmokeyBear.com’s current site has a section on “Benefits of Fire” that includes this information: “Fire managers can reintroduce fire into fire-dependent ecosystems with prescribed fire. Under specific, controlled conditions, the beneficial effects of natural fire can be recreated, fuel buildup can be reduced, and we can prevent the catastrophic losses of uncontrolled, unwanted wildfire.” Prescribed or controlled fire is an important resource management tool. It is a way to efficiently and safely provide for fire’s natural role in the ecosystem. However, the goal of Smokey Bear will always be to reduce the number of human-caused wildfires and reduce the loss of resources, homes and lives.[73]

See also

![]()

References

- ↑ "About the Campaign". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

On August 9, 1944, the creation of Smokey Bear was authorized by the Forest Service, and the first poster was delivered on October 10 by artist Albert Staehle.

- 1 2 3 Smokey Bear at Don Markstein's Toonopedia Archived from the original on June 5, 2017.

- ↑ Howe, Irving (1984). A Margin of Hope. Harvest Books. ISBN 978-0156572453.

excerpted in "Arguing the World". (official website) PBS.

Harold Rosenberg had an enviable part-time job at the Advertising Council, where he created Smokey the [sic] Bear. (The sheer deliciousness of it: this cuddly artifact of commercial folklore as the creature of our unyielding modernist!)

The official Smokey Bear website the by Ad Council does not mention Rosenberg. No mention is made of Smokey Bear at Rosenberg's obituary at Russell, John (July 13, 1978). "Harold Rosenberg Is Dead at 72 Art Critic for The New Yorker". The New York Times. - 1 2 "About Wildfires". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Newswire, MultiVu - PR. "Creative features new digital-first videos and artwork in a continuation of the longest running PSA campaign in U.S. history". Multivu. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- 1 2 3 "Explore Smokey Bear's History (1940s)". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "About the Campaign". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Wildfire Prevention". AdCouncil. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Wildfire Prevention". AdCouncil. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "The REAL Smokey Bear". The Unwritten Record. 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Orphan Cub". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ World Book Encyclopedia. Fire prevention. 1960.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Act of 1952" (PDF). U.S. Public Law 82-359, 66 Stat. 92. Government Printing Office. May 23, 1952. p. 92.

- ↑ "History of Smokey Bear". U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

- ↑ "Conservation Education - Smokey Bear - USDA Forest Service". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Campaign History — Forest Fire Prevention". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Morrison, Ellen Earnhardt (1989). Guardian of the forest : a history of the Smokey Bear program (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Morielle Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 0962253731. OCLC 20405393.

- ↑ Ralph Blumenthal (November 20, 2002). "Books of the Times: Their Battle Is Joined With an Inhuman Enemy". The New York Times. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Celebrates 70th Birthday Awards Smokey Bear Hugs In New Wildfire Prevention PSAs". AdCouncil. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Kelly, John (2010-04-25). "The biography of Smokey Bear: the cartoon came first". ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "The story of the creation of Smokey Bear, told by the late Albert Staehle's wife". South-florida.us. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Knickerbocker Bears antique teddy bear encyclopedia". Luckybears.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Japan's Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs". 2013-05-27. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Japanese balloon bomb killed six 60 years ago today". Herald and News. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Campaign History — American Icon". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Homer Pickens, 91 - Saved Smokey Bear". The New York Times. February 23, 1995. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Alex Hawes (December 2002). "Smokey Comes to Washington". Zoogoer. Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, John (2010-04-25). "The biography of Smokey Bear: the cartoon came first". ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Lawter, William Clifford (1994). Smokey Bear 20252 : a biography (1st ed.). Alexandria, VA: Lindsay Smith Publishers. p. 136. ISBN 0964001705. OCLC 30027766.

- ↑ Lawter, William Clifford (1994). Smokey Bear 20252 : a biography (1st ed.). Alexandria, VA: Lindsay Smith Publishers. p. 202. ISBN 0964001705. OCLC 30027766.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tad Bennicoff (May 27, 2010). "Bearly Survived to become an Icon". The Bigger Picture. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "About Smokey". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Welcome to Smokey Bear Historical Park!". Smokeybearpark.com. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Smokey's Grave Image".

- 1 2 3 John Kelly (April 25, 2010). "The biography of Smokey Bear: the cartoon came first". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ Larry Bleiberg (June 29, 1997). "New Mexico -- Town Still Celebrates Smokey Bear's Legend". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "National Zoological Park, Office of Public Affairs, Records". Record Unit 365. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ "National Association of State Foresters | Wildfire Prevention Tips and Campaign History". National Association of State Foresters. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Build a Campfire". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Equipment Use". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Backyard Burning". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Morrison, Ellen Earnhardt (1989). Guardian of the forest : a history of the Smokey Bear program (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Morielle Press. pp. 898–899. ISBN 0962253731. OCLC 20405393.

- ↑ "Letters to Smokey Bear Reveal Promise of Hope for the Future". USDA. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Explore Smokey Bear's History (1950s)". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Explore Smokey Bear's History (1960s)". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Forest Fire Prevention-Smokey Bear (1944-Present)". AdCouncil. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "About the Awards". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Awards Fact Sheet" (PDF). National Symbols Cache. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2006. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Index of /im/directives/fsh/1309.13". www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ Kathryn Sosbe (7 August 2014). "Smokey Bear, Iconic Symbol of Wildfire Prevention, Still Going Strong at 70". USDA. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Explore Smokey Bear's History (1990s)". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Explore Smokey Bear's History (1980s)". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ↑ Congressional Record, Senate, July 22, 2004. Books.google.com. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Richard Earle (2000). The Art of Cause Marketing. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 230.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Days -- Capitan, New Mexico". www.smokeybeardays.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ Neal Jones, originator of "Smokey Bear Days" 2000

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Returns to Remind Americans... "Only You Can Prevent Wildfires"". multivu.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Returns to Remind Americans ... "Only You Can Prevent Wildfires"". multivu.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Returns to Remind Americans..." AdCouncil. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear To Celebrate 68th Birthday At Mission Control". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Characters from Disney's Planes: Fire & Rescue Join Smokey Bear in New Wildfire Prevention PSAs". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "National Association of State Foresters | Wildfire Prevention Resource: New Smokey Bear PSAs Unveiled". National Association of State Foresters. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ Newswire, MultiVu - PR. "Creative features new digital-first videos and artwork in a continuation of the longest running PSA campaign in U.S. history". Multivu. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ "Jackson Weaver, 72, Voice of Smokey Bear". The New York Times. October 22, 1992. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ↑ Fisher, Ellyn (August 7, 2014). "SMOKEY BEAR CELEBRATES 70th BIRTHDAY AND REMINDS AMERICANS... "ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT WILDFIRES"" (Press release). Ad Council. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Smokey Bear Updates Part of New Ad Campaign". USDA Radio News. U.S. Dept of Agriculture. July 30, 2009. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Walt Disney - In The Bag - 1956, retrieved 2018-07-06

- ↑ dandydeal (2016-01-11), The Ballad of Smokey the Bear (1966), retrieved 2018-07-06

- 1 2 Morrison, Ellen Earnhardt (1995). Guardian of the forest : a history of Smokey Bear and the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Program (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Morielle Press. p. 61. ISBN 0962253758. OCLC 34884664.

- ↑ The Smokey Bear Show, Carl Banas, Billie Mae Richards, Paul Soles, retrieved 2018-07-06

- 1 2 Mike Anton (July 24, 2009). "At 65, Smokey Bear is still fighting fires". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ Swenson, Kyle (August 15, 2018). "Was Smokey Bear wrong? How a beloved character may have helped fuel catastrophic fires". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ↑ "Fire's Legacy". SmokeyBear.com. The Ad Council. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

External links

- SmokeyBear.com

- A collection of Smokey Bear-related media

- The Real Smokey Bear - slideshow by Life magazine

- Inventory of the Rudolph Wendelin Papers, 1930 - 2005 in the Forest History Society Library and Archives, Durham, NC

- Smokey Bear Days

- The short film History of Smokey Bear (ncwg.gov) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Smokey's Story, from the Texas Archive of the Moving Image