Animation

Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer-generated imagery (CGI). Computer animation can be very detailed 3D animation, while 2D computer animation can be used for stylistic reasons, low bandwidth or faster real-time renderings. Other common animation methods apply a stop motion technique to two and three-dimensional objects like paper cutouts, puppets or clay figures. The stop motion technique where live actors are used as a frame-by-frame subject is known as pixilation.

Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon and beta movement, but the exact causes are still uncertain. Analog mechanical animation media that rely on the rapid display of sequential images include the phénakisticope, zoetrope, flip book, praxinoscope and film. Television and video are popular electronic animation media that originally were analog and now operate digitally. For display on the computer, techniques like animated GIF and Flash animation were developed.

Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects.

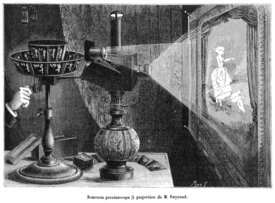

The physical movement of image parts through simple mechanics in for instance the moving images in magic lantern shows can also be considered animation. Mechanical animation of actual robotic devices is known as animatronics.

Animators are artists who specialize in creating animation.It can include from 2D games and movies(Anime) to 3D games

Etymology

The word "animation" stems from the Latin "animationem" (nominative "animatio"), noun of action from past participle stem of "animare", meaning "the action of imparting life". The primary meaning of the English word is "liveliness" and has been in use much longer than the meaning of "moving image medium".[1]

History

The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics.

A 5,200-year old pottery bowl discovered in Shahr-e Sukhteh, Iran, has five sequential images painted around it that seem to show phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree.[2][3] In 1833, the phenakistiscope introduced the stroboscopic principle of modern animation, which would also provide the basis for the zoetrope (1866), the flip book (1868), the praxinoscope (1877) and cinematography.

Charles-Émile Reynaud further developed his projection praxinoscope into the Théâtre Optique with transparent hand-painted colorful pictures in a long perforated strip wound between two spools, patented in December 1888. From 28 October 1892 to March 1900 Reynaud gave over 12,800 shows to a total of over 500.000 visitors at the Musée Grévin in Paris. His Pantomimes Lumineuses series of animated films each contained 300 to 700 frames that were manipulated back and forth to last 10 to 15 minutes per film. Piano music, song and some dialogue were performed live, while some sound effects were synchronized with an electromagnet.

When film became a common medium some manufacturers of optical toys adapted small magic lanterns into toy film projectors for short loops of film. By 1902, they were producing many chromolithography film loops, usually by tracing live-action film footage (much like the later rotoscoping technique).

Some early filmmakers, including J. Stuart Blackton, Arthur Melbourne-Cooper, Segundo de Chomón and Edwin S. Porter experimented with stop-motion animation, possibly since around 1899. Blackton's The Haunted Hotel (1907) was the first huge success that baffled audiences with objects apparently moving by themselves and inspired other filmmakers to try the technique for themselves.

J. Stuart Blackton also experimented with animation drawn on blackboards and some cutout animation in Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906).

In 1908, Émile Cohl's Fantasmagorie was released with a white-on-black chalkline look created with negative prints from black ink drawings on white paper.[4] The film largely consists of a stick figure moving about and encountering all kinds of morphing objects, including a wine bottle that transforms into a flower.[5]

Inspired by Émile Cohl's stop-motion film Les allumettes animées [Animated Matches] (1908), Ladislas Starevich started making his influential puppet animations in 1910.

Winsor McCay's Little Nemo (1911) showcased very detailed drawings. His Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) was an also an early example of character development in drawn animation.[6]

During the 1910s, the production of animated short films typically referred to as "cartoons", became an industry of its own and cartoon shorts were produced for showing in movie theaters.[7] The most successful producer at the time was John Randolph Bray, who, along with animator Earl Hurd, patented the cel animation process that dominated the animation industry for the rest of the decade.[8][9]

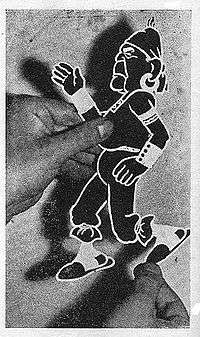

El Apóstol (Spanish: "The Apostle") was a 1917 Argentine animated film utilizing cutout animation, and the world's first animated feature film.[11][12] Unfortunately, a fire that destroyed producer Federico Valle's film studio incinerated the only known copy of El Apóstol, and it is now considered a lost film.[13][14]

The earliest extant feature-length animated film is The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) made by director Lotte Reiniger and her collaborators Carl Koch and Berthold Bartosch.

In 1932, the first short animated film created entirely with Technicolor (using red/green/blue photographic filters and three strips of film) was Walt Disney's Flowers and Trees, directed by Burt Gillett. But, the first feature film that was done with this technique, apart from the movie The Vanities Fair (1935), by Rouben Mamoulian, was "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs", also by Walt Disney.[15]

In 1958, Hanna-Barbera released The Huckleberry Hound Show, the first half hour television program to feature only in animation.[16] Terrytoons released Tom Terrific that same year.[17][18] Television significantly decreased public attention to the animated shorts being shown in theaters.[16]

Computer animation has become popular since Toy Story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique.[19]

In 2008, the animation market was worth US$68.4 billion.[20] Animation as an art and industry continues to thrive as of the mid-2010s because well-made animated projects can find audiences across borders and in all four quadrants. Animated feature-length films returned the highest gross margins (around 52%) of all film genres in the 2004–2013 timeframe.[21]

Techniques

Traditional animation

Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century.[22] The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper.[23] To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels,[24] which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings.[25] The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by a rostrum camera onto motion picture film.[26]

The traditional cel animation process became obsolete by the beginning of the 21st century. Today, animators' drawings and the backgrounds are either scanned into or drawn directly into a computer system.[27][28] Various software programs are used to color the drawings and simulate camera movement and effects.[29] The final animated piece is output to one of several delivery media, including traditional 35 mm film and newer media with digital video.[30][27] The "look" of traditional cel animation is still preserved, and the character animators' work has remained essentially the same over the past 70 years.[31] Some animation producers have used the term "tradigital" (a play on the words "traditional" and "digital") to describe cel animation that uses significant computer technology.

Examples of traditionally animated feature films include Pinocchio (United States, 1940),[32] Animal Farm (United Kingdom, 1954), Lucky and Zorba (Italy, 1998), and The Illusionist (British-French, 2010). Traditionally animated films produced with the aid of computer technology include The Lion King (US, 1994), The Prince of Egypt (US, 1998), Akira (Japan, 1988),[33] Spirited Away (Japan, 2001), The Triplets of Belleville (France, 2003), and The Secret of Kells (Irish-French-Belgian, 2009).

Full animation

Full animation refers to the process of producing high-quality traditionally animated films that regularly use detailed drawings and plausible movement,[34] having a smooth animation.[35] Fully animated films can be made in a variety of styles, from more realistically animated works like those produced by the Walt Disney studio (The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King) to the more 'cartoon' styles of the Warner Bros. animation studio. Many of the Disney animated features are examples of full animation, as are non-Disney works, The Secret of NIMH (US, 1982), The Iron Giant (US, 1999), and Nocturna (Spain, 2007). Fully animated films are animated at 24 frames per second, with a combination of animation on ones and twos, meaning that drawings can be held for one frame out of 24 or two frames out of 24.[36]

Limited animation

Limited animation involves the use of less detailed or more stylized drawings and methods of movement usually a choppy or "skippy" movement animation.[37] Limited animation uses fewer drawings per second, thereby limiting the fluidity of the animation. This is a more economic technique. Pioneered by the artists at the American studio United Productions of America,[38] limited animation can be used as a method of stylized artistic expression, as in Gerald McBoing-Boing (US, 1951), Yellow Submarine (UK, 1968), and certain anime produced in Japan.[39] Its primary use, however, has been in producing cost-effective animated content for media for television (the work of Hanna-Barbera,[40] Filmation,[41] and other TV animation studios[42]) and later the Internet (web cartoons).

Rotoscoping

Rotoscoping is a technique patented by Max Fleischer in 1917 where animators trace live-action movement, frame by frame.[43] The source film can be directly copied from actors' outlines into animated drawings,[44] as in The Lord of the Rings (US, 1978), or used in a stylized and expressive manner, as in Waking Life (US, 2001) and A Scanner Darkly (US, 2006). Some other examples are Fire and Ice (US, 1983), Heavy Metal (1981), and Aku no Hana (2013).

Live-action/animation

Live-action/animation is a technique combining hand-drawn characters into live action shots or live action actors into animated shots.[45] One of the earlier uses was in Koko the Clown when Koko was drawn over live action footage.[46] Other examples include Allegro Non Troppo (Italy, 1976), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (US, 1988), Space Jam (US, 1996) and Osmosis Jones (US, 2001).

Stop motion animation

Stop-motion animation is used to describe animation created by physically manipulating real-world objects and photographing them one frame of film at a time to create the illusion of movement.[47] There are many different types of stop-motion animation, usually named after the medium used to create the animation.[48] Computer software is widely available to create this type of animation; traditional stop motion animation is usually less expensive but more time-consuming to produce than current computer animation.[48]

- Puppet animation typically involves stop-motion puppet figures interacting in a constructed environment, in contrast to real-world interaction in model animation.[49] The puppets generally have an armature inside of them to keep them still and steady to constrain their motion to particular joints.[50] Examples include The Tale of the Fox (France, 1937), The Nightmare Before Christmas (US, 1993), Corpse Bride (US, 2005), Coraline (US, 2009), the films of Jiří Trnka and the adult animated sketch-comedy television series Robot Chicken (US, 2005–present).

- Puppetoon, created using techniques developed by George Pal,[51] are puppet-animated films that typically use a different version of a puppet for different frames, rather than simply manipulating one existing puppet.[52]

- Clay animation, or Plasticine animation (often called claymation, which, however, is a trademarked name), uses figures made of clay or a similar malleable material to create stop-motion animation.[47][53] The figures may have an armature or wire frame inside, similar to the related puppet animation (below), that can be manipulated to pose the figures.[54] Alternatively, the figures may be made entirely of clay, in the films of Bruce Bickford, where clay creatures morph into a variety of different shapes. Examples of clay-animated works include The Gumby Show (US, 1957–1967), Mio Mao (Italy, 1974-2005), Morph shorts (UK, 1977–2000), Wallace and Gromit shorts (UK, as of 1989), Jan Švankmajer's Dimensions of Dialogue (Czechoslovakia, 1982), The Trap Door (UK, 1984). Films include Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Chicken Run and The Adventures of Mark Twain.[55]

- Strata-cut animation, Strata-cut animation is most commonly a form of clay animation in which a long bread-like "loaf" of clay, internally packed tight and loaded with varying imagery, is sliced into thin sheets, with the animation camera taking a frame of the end of the loaf for each cut, eventually revealing the movement of the internal images within.[56]

- Cutout animation is a type of stop-motion animation produced by moving two-dimensional pieces of material paper or cloth.[57] Examples include Terry Gilliam's animated sequences from Monty Python's Flying Circus (UK, 1969–1974); Fantastic Planet (France/Czechoslovakia, 1973) ; Tale of Tales (Russia, 1979), The pilot episode of the adult television sitcom series (and sometimes in episodes) of South Park (US, 1997) and the music video Live for the moment, from Verona Riots band (produced by Alberto Serrano and Nívola Uyá, Spain 2014).

- Silhouette animation is a variant of cutout animation in which the characters are backlit and only visible as silhouettes.[58] Examples include The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Weimar Republic, 1926) and Princes et princesses (France, 2000).

- Model animation refers to stop-motion animation created to interact with and exist as a part of a live-action world.[59] Intercutting, matte effects and split screens are often employed to blend stop-motion characters or objects with live actors and settings.[60] Examples include the work of Ray Harryhausen, as seen in films, Jason and the Argonauts (1963),[61] and the work of Willis H. O'Brien on films, King Kong (1933).

- Go motion is a variant of model animation that uses various techniques to create motion blur between frames of film, which is not present in traditional stop-motion.[62] The technique was invented by Industrial Light & Magic and Phil Tippett to create special effect scenes for the film The Empire Strikes Back (1980).[63] Another example is the dragon named "Vermithrax" from Dragonslayer (1981 film).[64]

- Object animation refers to the use of regular inanimate objects in stop-motion animation, as opposed to specially created items.[65]

- Graphic animation uses non-drawn flat visual graphic material (photographs, newspaper clippings, magazines, etc.), which are sometimes manipulated frame-by-frame to create movement.[66] At other times, the graphics remain stationary, while the stop-motion camera is moved to create on-screen action.

- Brickfilm are a subgenre of object animation involving using Lego or other similar brick toys to make an animation.[67][68] These have had a recent boost in popularity with the advent of video sharing sites, YouTube and the availability of cheap cameras and animation software.[69]

- Pixilation involves the use of live humans as stop motion characters.[70] This allows for a number of surreal effects, including disappearances and reappearances, allowing people to appear to slide across the ground, and other effects.[70] Examples of pixilation include The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb and Angry Kid shorts, and the academy award-winning Neighbours by Norman McLaren.

Computer animation

Computer animation encompasses a variety of techniques, the unifying factor being that the animation is created digitally on a computer.[29][71] 2D animation techniques tend to focus on image manipulation while 3D techniques usually build virtual worlds in which characters and objects move and interact.[72] 3D animation can create images that seem real to the viewer.[73]

2D animation

2D animation figures are created or edited on the computer using 2D bitmap graphics and 2D vector graphics.[74] This includes automated computerized versions of traditional animation techniques, interpolated morphing,[75] onion skinning[76] and interpolated rotoscoping.

2D animation has many applications, including analog computer animation, Flash animation, and PowerPoint animation. Cinemagraphs are still photographs in the form of an animated GIF file of which part is animated.[77]

Final line advection animation is a technique used in 2D animation,[78] to give artists and animators more influence and control over the final product as everything is done within the same department.[79] Speaking about using this approach in Paperman, John Kahrs said that "Our animators can change things, actually erase away the CG underlayer if they want, and change the profile of the arm."[80]

3D animation

3D animation is digitally modeled and manipulated by an animator. The animator usually starts by creating a 3D polygon mesh to manipulate.[81] A mesh typically includes many vertices that are connected by edges and faces, which give the visual appearance of form to a 3D object or 3D environment.[81] Sometimes, the mesh is given an internal digital skeletal structure called an armature that can be used to control the mesh by weighting the vertices.[82][83] This process is called rigging and can be used in conjunction with keyframes to create movement.[84]

Other techniques can be applied, mathematical functions (e.g., gravity, particle simulations), simulated fur or hair, and effects, fire and water simulations.[85] These techniques fall under the category of 3D dynamics.[86]

3D terms

- Cel-shaded animation is used to mimic traditional animation using computer software.[87] Shading looks stark, with less blending of colors. Examples include Skyland (2007, France), The Iron Giant (1999, United States), Futurama (Fox, 1999) Appleseed Ex Machina (2007, Japan), The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2002, Japan), The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017, Japan)

- Machinima – Films created by screen capturing in video games and virtual worlds. The term originated from the software introduction in the 1980s demoscene, as well as the 1990s recordings of the first-person shooter video game Quake.

- Motion capture is used when live-action actors wear special suits that allow computers to copy their movements into CG characters.[88][89] Examples include Polar Express (2004, US), Beowulf (2007, US), A Christmas Carol (2009, US), The Adventures of Tintin (2011, US) kochadiiyan (2014, India)

- Photo-realistic animation is used primarily for animation that attempts to resemble real life, using advanced rendering that mimics in detail skin, plants, water, fire, clouds, etc.[90] Examples include Up (2009, US), How to Train Your Dragon (2010, US)

Mechanical animation

- Animatronics is the use of mechatronics to create machines that seem animate rather than robotic.

- Audio-Animatronics and Autonomatronics is a form of robotics animation, combined with 3-D animation, created by Walt Disney Imagineering for shows and attractions at Disney theme parks move and make noise (generally a recorded speech or song).[91] They are fixed to whatever supports them. They can sit and stand, and they cannot walk. An Audio-Animatron is different from an android-type robot in that it uses prerecorded movements and sounds, rather than responding to external stimuli. In 2009, Disney created an interactive version of the technology called Autonomatronics.[92]

- Linear Animation Generator is a form of animation by using static picture frames installed in a tunnel or a shaft. The animation illusion is created by putting the viewer in a linear motion, parallel to the installed picture frames.[93] The concept and the technical solution were invented in 2007 by Mihai Girlovan in Romania.

- Chuckimation is a type of animation created by the makers of the television series Action League Now! in which characters/props are thrown, or chucked from off camera or wiggled around to simulate talking by unseen hands.[94]

- The magic lantern used mechanical slides to project moving images, probably since Christiaan Huygens invented this early image projector in 1659.

Other animation styles, techniques, and approaches

- Hydrotechnics: a technique that includes lights, water, fire, fog, and lasers, with high-definition projections on mist screens.

- Drawn on film animation: a technique where footage is produced by creating the images directly on film stock, for example by Norman McLaren,[95] Len Lye and Stan Brakhage.

- Paint-on-glass animation: a technique for making animated films by manipulating slow drying oil paints on sheets of glass,[96] for example by Aleksandr Petrov.

- Erasure animation: a technique using traditional 2D media, photographed over time as the artist manipulates the image. For example, William Kentridge is famous for his charcoal erasure films,[97] and Piotr Dumała for his auteur technique of animating scratches on plaster.

- Pinscreen animation: makes use of a screen filled with movable pins that can be moved in or out by pressing an object onto the screen.[98] The screen is lit from the side so that the pins cast shadows. The technique has been used to create animated films with a range of textural effects difficult to achieve with traditional cel animation.[99]

- Sand animation: sand is moved around on a back- or front-lighted piece of glass to create each frame for an animated film.[100] This creates an interesting effect when animated because of the light contrast.[101]

- Flip book: a flip book (sometimes, especially in British English, called a flick book) is a book with a series of pictures that vary gradually from one page to the next, so that when the pages are turned rapidly, the pictures appear to animate by simulating motion or some other change.[102][103] Flip books are often illustrated books for children,[104] they also be geared towards adults and employ a series of photographs rather than drawings. Flip books are not always separate books, they appear as an added feature in ordinary books or magazines, often in the page corners.[102] Software packages and websites are also available that convert digital video files into custom-made flip books.[105]

- Character animation

- Multi-sketching

- Special effects animation

Animator

An animator is an artist who creates a visual sequence (or audio-visual if added sound) of multiple sequential images that generate the illusion of movement, that is, an animation. Animations are currently in many areas of technology and video, such as cinema, television, video games or the internet. Generally, these works require the collaboration of several animators. The methods to create these images depend on the animator and style that one wants to achieve (with images generated by computer, manually ...).

Animators can be divided into animators of characters (artists who are specialized in the movements, dialogue and acting of the characters) and animators of special effects (for example vehicles, machinery or natural phenomena such as water, snow, rain).

Production

The creation of non-trivial animation works (i.e., longer than a few seconds) has developed as a form of filmmaking, with certain unique aspects.[106] Traits common to both live-action and animated feature-length films are labor-intensity and high production costs.[107]

The most important difference is that once a film is in the production phase, the marginal cost of one more shot is higher for animated films than live-action films.[108] It is relatively easy for a director to ask for one more take during principal photography of a live-action film, but every take on an animated film must be manually rendered by animators (although the task of rendering slightly different takes has been made less tedious by modern computer animation).[109] It is pointless for a studio to pay the salaries of dozens of animators to spend weeks creating a visually dazzling five-minute scene if that scene fails to effectively advance the plot of the film.[110] Thus, animation studios starting with Disney began the practice in the 1930s of maintaining story departments where storyboard artists develop every single scene through storyboards, then handing the film over to the animators only after the production team is satisfied that all the scenes make sense as a whole. [111] While live-action films are now also storyboarded, they enjoy more latitude to depart from storyboards (i.e., real-time improvisation).[112]

Another problem unique to animation is the requirement to maintain a film's consistency from start to finish, even as films have grown longer and teams have grown larger. Animators, like all artists, necessarily have individual styles, but must subordinate their individuality in a consistent way to whatever style is employed on a particular film.[113] Since the early 1980s, teams of about 500 to 600 people, of whom 50 to 70 are animators, typically have created feature-length animated films. It is relatively easy for two or three artists to match their styles; synchronizing those of dozens of artists is more difficult.[114]

This problem is usually solved by having a separate group of visual development artists develop an overall look and palette for each film before animation begins. Character designers on the visual development team draw model sheets to show how each character should look like with different facial expressions, posed in different positions, and viewed from different angles.[115][116] On traditionally animated projects, maquettes were often sculpted to further help the animators see how characters would look from different angles.[31][115]

Unlike live-action films, animated films were traditionally developed beyond the synopsis stage through the storyboard format; the storyboard artists would then receive credit for writing the film.[117] In the early 1960s, animation studios began hiring professional screenwriters to write screenplays (while also continuing to use story departments) and screenplays had become commonplace for animated films by the late 1980s.

Criticism

Criticism of animation has been common in media and cinema since its inception. With its popularity, a large amount of criticism has arisen, especially animated feature-length films.[118] Many concerns of cultural representation, psychological effects on children have been brought up around the animation industry, which has remained rather politically unchanged and stagnant since its inception into mainstream culture.[119]

Awards

As with any other form of media, animation too has instituted awards for excellence in the field. The original awards for animation were presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for animated shorts from the year 1932, during the 5th Academy Awards function. The first winner of the Academy Award was the short Flowers and Trees,[120] a production by Walt Disney Productions.[121][122] The Academy Award for a feature-length animated motion picture was only instituted for the year 2001, and awarded during the 74th Academy Awards in 2002. It was won by the film Shrek, produced by DreamWorks and Pacific Data Images.[123] Disney/Pixar have produced the most films either to win or be nominated for the award. The list of both awards can be obtained here:

Several other countries have instituted an award for best animated feature film as part of their national film awards: Africa Movie Academy Award for Best Animation (since 2008), BAFTA Award for Best Animated Film (since 2006), César Award for Best Animated Film (since 2011), Golden Rooster Award for Best Animation (since 1981), Goya Award for Best Animated Film (since 1989), Japan Academy Prize for Animation of the Year (since 2007), National Film Award for Best Animated Film (since 2006). Also since 2007, the Asia Pacific Screen Award for Best Animated Feature Film has been awarded at the Asia Pacific Screen Awards. Since 2009, the European Film Awards have awarded the European Film Award for Best Animated Film.

The Annie Award is another award presented for excellence in the field of animation. Unlike the Academy Awards, the Annie Awards are only received for achievements in the field of animation and not for any other field of technical and artistic endeavor. They were re-organized in 1992 to create a new field for Best Animated feature. The 1990s winners were dominated by Walt Disney, however, newer studios, led by Pixar & DreamWorks, have now begun to consistently vie for this award. The list of awardees is as follows:

See also

- 12 basic principles of animation

- Animated war film

- Animation department

- Animation software

- Anime

- Architectural animation

- Avar (animation variable)

- Computer-generated imagery

- Independent animation

- International Animated Film Association

- International Tournée of Animation

- List of motion picture topics

- Model sheet

- Motion graphic design

- Society for Animation Studies

- Tradigital art

- Wire-frame model

References

Citations

- ↑ http://www.dictionary.com/browse/animation

- ↑ Cohn, Neil (February 15, 2006). "The Visual Linguist: Burnt City animation VL". The Visual Linguist.

- ↑ Ball, Ryan (March 12, 2008). "Oldest Animation Discovered In Iran". Animation Magazine.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, p. 42

- ↑ Canemaker 2005, p. 171.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 28.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 24.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 34.

- ↑ Bendazzi 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ Finkielman 2004.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, p. 378.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Bendazzi 1996.

- ↑ "¿Cuál fue la primera película en color?". Esquire (in Spanish). 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- 1 2 Bendazzi 1994, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 432.

- ↑ Board of Investments 2009.

- ↑ McDuling 2014.

- ↑ White 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 153.

- ↑ Thomas & Johnston 1981, pp. 277–279.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, p. 203.

- ↑ White 2006, pp. 195–201.

- 1 2 Buchan 2013.

- ↑ White 2006, p. 394.

- 1 2 Culhane 1990, p. 296.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 35–36, 52–53.

- 1 2 Williams 2001, pp. 52–57.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Culhane 1990, p. 71.

- ↑ Culhane 1990, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 142.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Ledoux 1997, p. 24, 29.

- ↑ Lawson & Persons 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 241.

- ↑ Lawson & Persons 2004, p. xxi.

- ↑ Crafton 1993, p. 158.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Beck 2004, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Solomon 1989, p. 299.

- 1 2 Laybourne 1998, p. 159.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 171.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Beck 2004, p. 70.

- ↑ Beck 2004, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 150-151.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 151–154.

- ↑ Beck 2004, p. 250.

- ↑ Furniss 1998, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Culhane 1990, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, pp. 222–226

- ↑ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, p. 18

- ↑ Smith 1986, p. 90.

- ↑ Watercutter 2012.

- ↑ Smith 1986, pp. 91–95.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 51–57.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, p. 128.

- ↑ Paul 2005, pp. 357–363.

- ↑ Herman 2014.

- ↑ Haglund 2014.

- 1 2 Laybourne 1998, pp. 75–79.

- ↑ Serenko 2007.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 405.

- ↑ Serenko 2007, p. 482.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 165.

- ↑ Sito 2013, pp. 32, 70, 132.

- ↑ Priebe 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ White 2006, p. 392.

- ↑ Lowe & Schnotz 2008, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Masson 2007, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Beck 2012.

- 1 2 Masson 2007, p. 88.

- ↑ Sito 2013, p. 208.

- ↑ Masson 2007, pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Sito 2013, p. 285.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 96.

- ↑ Lowe & Schnotz 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ "Cel Shading: the Unsung Hero of Animation?". Animator Mag. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Sito 2013, pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 204.

- ↑ Parent 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ Pilling 1997, p. 249.

- ↑ O'Keefe 2014.

- ↑ Parent 2007, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Kenyon 1998.

- ↑ Faber & Walters 2004, p. 1979.

- ↑ Pilling 1997, p. 222.

- ↑ Carbone 2010.

- ↑ Neupert 2011.

- ↑ Pilling 1997, p. 204.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 7.

- ↑ Furniss 1998, pp. 30–33.

- 1 2 Laybourne 1998, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, p. xiv.

- ↑ White 2006, p. 203.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, p. 117.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 274.

- ↑ White 2006, p. 151.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, p. 339.

- ↑ Culhane 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Solomon 1989, p. 120.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Masson 2007, p. 94.

- ↑ Beck 2004, p. 37.

- 1 2 Williams 2001, p. 34.

- ↑ Culhane 1990, p. 146.

- ↑ Laybourne 1998, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Amidi 2011.

- ↑ Nagel 2008.

- ↑ Walt Disney Family Museum 2013.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, p. 37.

- ↑ Shaffer 2010, p. 211.

- ↑ Beckerman 2003, pp. 84–85.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Joseph and Barbara (Spring 1993). "Journal of Film and Video". The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited. University of Central Arkansas. 45 (1): 3–13. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.

- Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art. State University of New York Press. pp. 58, 86, 143, 151, 176, 201, 226, 243, 292, 304. ISBN 0-87395-602-8.

- Beck, Jerry (2004). Animation Art: From Pencil to Pixel, the History of Cartoon, Anime & CGI. Fulhamm London: Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84451-140-2.

- Beckerman, Howard (2003). Animation: The Whole Story. Allworth Press. ISBN 1-58115-301-5.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1994). Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20937-4.

- Buchan, Suzanne (2013). Pervasive Animation. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-80723-4.

- Canemaker, John (2005). Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (Revised ed.). Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-5941-5.

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898–1928. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11667-0.

- Culhane, Shamus (1990). Animation: Script to Screen. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-05052-6.

- Drazin, Charles (March 17, 2011). The Faber Book of French Cinema. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21849-3.

- Finkielman, Jorge (2004). The Film Industry in Argentina: An Illustrated Cultural History. North Carolina: McFarland. p. 20. ISBN 0-7864-1628-9.

- Furniss, Maureen (1998). Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. Indiana University Press. ISBN 1-86462-039-0.

- Faber, Liz; Walters, Helen (2004). Animation Unlimited: Innovative Short Films Since 1940. London: Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 1-85669-346-5.

- Godfrey, Bob; Jackson, Anna (1974). The Do-It-Yourself Film Animation Book. BBC Publications. ISBN 978-0-563-10829-0.

- Harryhausen, Ray; Dalton, Tony (2008). A Century of Model Animation: From Méliès to Aardman. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-0-8230-9980-1.

- Laybourne, Kit (1998). The Animation Book: A Complete Guide to Animated Filmmaking– from Flip-books to Sound Cartoons to 3-D Animation. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-88602-2.

- Lawson, Tim; Persons, Alisa (2004). The Magic Behind the Voices [A Who's Who of Cartoon Voice Actors]. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-696-4.

- Ledoux, Trish (1997). Complete Anime Guide: Japanese Animation Film Directory and Resource Guide. Tiger Mountain Press. ISBN 0-9649542-5-7.

- Lowe, Richard; Schnotz, Wolfgang, eds. (2008). Learning with Animation. Research implications for design. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85189-3.

- Masson, Terrence (2007). CG101: A Computer Graphics Industry Reference. Unique and personal histories of early computer animation production, plus a comprehensive foundation of the industry for all reading levels. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Digital Fauxtography. ISBN 978-0-9778710-0-1.

- Needham, Joseph (1962). "Science and Civilization in China". Physics and Physical Technology. IV. Cambridge University Press.

- Parent, Rick (November 1, 2007). Computer Animation: Algorithms & Techniques. Ohio State University: Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-532000-9.

- Paul, Joshua (2005). Digital Video Hacks. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00946-1.

- Pilling, Jayne (1997). Society of Animation Studies, ed. A Reader in Animation Studies. Indiana University Press. ISBN 1-86462-000-5.

- Priebe, Ken A. (2006). The Art of Stop-Motion Animation. Thompson Course Technology. ISBN 1-59863-244-2.

- Neupert, Richard (2011). French Animation History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3836-2.

- Rojas, Carlos; Chow, Eileen (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-998844-0.

- Herman, Sarah (2014). Brick Flicks: A Comprehensive Guide to Making Your Own Stop-Motion LEGO Movies. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62914-649-2.

- Serenko, Alexander (2007). "Computers in Human Behavior" (PDF). The development of an instrument to measure the degree of animation predisposition of agent users. 23 (1): 478–495.

- Shaffer, Joshua C. (September 24, 2010). Discovering The Magic Kingdom: An Unofficial Disneyland Vacation Guide. Indiana: Author House. ISBN 978-1-4520-6312-6.

- Solomon, Charles (1989). Enchanted Drawings: The History of Animation. New York: Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-394-54684-1.

- Thomas, Bob (1958). Walt Disney, the Art of Animation: The Story of the Disney Studio Contribution to a New Art. Walt Disney Studios. Simon and Schuster.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1981). Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life. Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-89659-233-2.

- Zielinski, Siegfried (1999). Audiovisions: Cinema and Television as Entr'actes in History. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-303-2.

- Sito, Tom (2013). Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation. Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01909-5.

- Smith, Thomas G. (1986). Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-32263-0.

- White, Tony (2006). Animation from Pencils to Pixels: Classical Techniques for the Digital Animator. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-240-80670-9.

- Williams, Richard (2001). The Animator's Survival Kit. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20228-7.

Online sources

- Amidi, Amid (2 December 2011). "NY Film Critics Didn't like a Single Animated Film This Year". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Ball, Ryan (March 12, 2008). "Oldest Animation Discovered In Iran". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Beck, Jerry (July 2, 2012). "A Little More About Disney's "Paperman"". Cartoon Brew.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1996). "The Untold Story of Argentina's Pioneer Animator". Animation World Network. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- Bhattacgarjee, Subhankar (December 2, 2015). "A short history of Animation, before Disney". Medium. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Animation" (PDF). boi.gov.ph. Board of Investments. November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Brown, Margery (2003). "Experimental Animation Techniques" (PDF). Olympia, Washington: Evergreen State Collage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 2005-11-11.

- Carbone, Ken (February 24, 2010). "Stone-Age Animation in a Digital World: William Kentridge at MoMA". Fast Company. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Haglund, David (7 February 2014). "The Oldest Known LEGO Movie". Slate. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "World's Oldest Animation?". theheritagetrust.wordpress.com. The Heritage Trust. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015.

- Kenyon, Heather (February 1, 1998). "How'd They Do That?: Stop-Motion Secrets Revealed". Animation World Network. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Nagel, Jan (May 21, 2008). "Gender in Media: Females Don't Rule". Animation World Network. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- McDuling, John (3 July 2014). "Hollywood Is Giving Up on Comedy". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- McLaughlin, Dan (2001). "A RATHER INCOMPLETE BUT STILL FASCINATING". Film Tv. UCLA. Archived from the original on November 19, 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- O'Keefe, Matt (November 11, 2014). "6 Major Innovations That Sprung from the Heads of Disney Imagineers". Theme Park Tourist. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Watercutter, Angela (May 24, 2012). "35 Years After Star Wars, Effects Whiz Phil Tippett Is Slowly Crafting a Mad God". Wired. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- Zohn, Patricia (February 28, 2010). "Coloring the Kingdom". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "Walt Disney's Oscars". The Walt Disney Family Museum. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- "Władysław Starewicz - Biography". culture.pl. Adam Mickiewicz Institute. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Animation |

| Look up animation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Animations. |

| Library resources about Animation |

- The making of an 8-minute cartoon short

- Importance of animation and its utilization in varied industries

- "Animando", a 12-minute film demonstrating 10 different animation techniques (and teaching how to use them).

- 19 types of animation techniques and styles

- Animation at Curlie (based on DMOZ)