Slovak Three

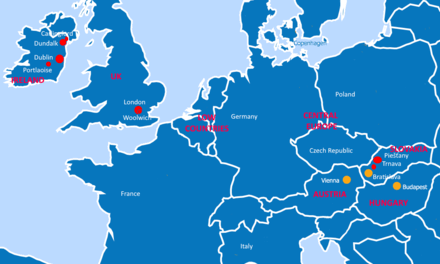

The Slovak Three[1][note 1] were three Irishmen—Michael Christopher McDonald, Declan John Rafferty and Fintan Paul O'Farrell[2]—who were members of the Real IRA. They were arrested in a MI5 sting operation in Slovakia, after they were caught attempting to buy arms for their campaign in 2001. They believed that they were purchasing weapons from Iraqi intelligence agents and that Saddam Hussein was to play a similar role to their organisation as Colonel Gadaffi had to their predecessors, the Provisional IRA. After months of meetings and telephone calls—all intercepted and overheard by MI6—the three men met in Piešťany, a spa town in Western Slovakia. MI5, believing their case to be now fireproof, had passed on the details of the men and their intentions to the Slovak authorities, who, on the evening of 5 July 2001 ambushed the three men after their meeting. They were arrested and imprisoned in the expectation that Slovakia would receive a formal extradition request fro the UK.

They were extradited and eventually sentenced at Woolwich Crown Court to 30 years imprisonment; unusually for IRA men in British courts, they pled guilty. In 2006 they were transferred to Ireland to serve the remainder of their sentence in Portlaoise Prison. However, in 2014 it was discovered that some prisoners who had been transferred from the English penal system to the Irish one had not had their warrants adjusted to take into account the fact that Ireland had no facility to release prisoners on licence. This resulted in anomalies between what they had been sentenced to in England and what they were expected to serve in Ireland; after an appeal, the Irish High Court released them in September.

Background

In July 1997 the Provisional IRA, which had been waging an armed campaign against the British government for the previous 30 years, called a ceasefire. Subsequently, at an IRA Convention in County Donegal, the organisation's Quartermaster and Executive member, Michael McKevitt denounced the ceasefire and the fledgling Northern Ireland peace process, urging for a return to the armed struggle. However, he was outmanoeuvred and isolated by the Adams-McGuinness leadership,[3][4] and, along with his supporters, resigned.[5] In November the same year, McKevitt and his supprters formed a new group, the Real IRA,[6] which attracted disaffected Republicans from across the country.[7][8]

McKevitt, as Quartermaster, had access to the IRA's major arms dumps, and when he left he took with him a small amount[9] of materiel, including Semtex, various guns including Uzi submachine guns, AK-47 and AK-74, and detonators and timing devices.[10][8] Within a few years, the group was able to supplement its equipment with imported arms and explosives. Much of this came from the former Yugoslavia,[11] which at the time had a flourishing black market in weaponry following the Yugoslav Wars of the previous decade.[12] The group was not always successful: in July 2000, the Croatian police[13] successfully seized a large quantity of weapons destined for Dublin in Dobranje.[12] By the following year, a number of RIRA arms dumps had been discovered in Ireland, most of the seized weapons were from Eastern Europe.[12][14] As well as Irish Republicans, Ulster loyalist groups also obtained arms from the same region, but by 2001 the countries concerned were attempting to stem the practice as part of the process of joining the European Union.[12][note 2] The RIRA, for their part, wished to receive the sponsorship of a rogue state and believed that with Saddam Hussein's Iraq[19] they would receive both guns and money for their cause[20] and create a supply line for the future.[21][note 3] The group had recently carried out some high-profile attacks in England the previous year, bombing BBC Television Center in White City in March,[23] Hammersmith Bridge in June 2000,[24] and Ealing Broadway in August, [25] In September the same year they launched a rocket-propelled grenade on the MI6 headquarters in Vauxhall;[26] the RPG-18 used in the attack may have been purchased in the Balkans.[17]

MI5 chose the Iraqi storyline for their sting in the belief that it "might prove alluring". The so-called political wing of the RIRA, the 32 County Sovereignty Movement (32CSM), had recently published articles on their website condemning Britain for bombing Iraq in 1998.[27] The fake Iraqi gunrunners first established contact with the Republicans through the 32CSM's press officer, Joe Dillon, reported The Daily Telegraph.[27] At first, they claimed to be Iraqi journalists, merely interested in the Real IRA[27] and British imperialism; they left a mobile phone to be contacted on.[28] Only later did they claim to be Iraqi intelligence personnel.[27]

O'Farrell, Rafferty and McDonald

All three were from the Cooley Peninsula in County Louth:[29] O'Farrell and Rafferty from Carlingford McDonald from Dundalk.[20] Their IRA activities were known to the Gardai.[12] An old friendship existed between the three, as well as between their families, and it was later suggested in court that they may have been inspired as much by loyalties to each other as to politics.[28] McDonald had a reputation for violence and was suspected by the Gardaí of at least one killing.[30] He may have been second-in-command to McKevitt in Ireland within the group,[31] and also led the team in Slovakia.[27] At their later trial, all three were described as being "leading figures"[22] in the organization.[22] O'Farrell and Rafferty were 35 and 41 years of age respectively when they were arrested.[27]

Operation Samnite

The Real IRA's plans for the continent were originally discovered by Slovak intelligence in 2000, which informed MI5.[32] The British operation, called Operation Samnite,[33] took six months to come to fruition in the following year,[12] and involved up to 50 members of MI5.[22] The RIRA had "an extensive shopping list"[34] of weaponry it wished to acquire.[34] Having agreed to meet who they thought was an Iraqi agent named Sami, another Louth man—and close associate of McKevitt—made the first trip to Slovakia. He was under surveillance from the beginning.[29] The Irishmen believed that they were negotiating with Iraqi intelligence agents sent by Saddam Hussein,[35] from whom they believed they were buying 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) of semtex plastic explosive, 2000 detonators, 200 grenade and 500 pistols.[30][note 4] MacDonald may have had hopes of obtaining a variety of supergun that the Iraqi government was suspected to possess. Such a weapon, combined with wire-guided missiles— also requested by McDonald—would have enabled the Real IRA[30] to have pierced everything from armour plating to the bulletproof vests worn by the Police Service of Northern Ireland[1] and the British army.[1]

Following the purchase, they intended to make two shipments[30] to Ireland overland through Central Europe[14] and the Low Countries.[30] The first shipment was to bring 2,000 kilograms (4,400 lb) of plastic explosives, 100 grenades, 125 pistols and 125 automatic weapons. Another shipment was to bring the remainder.[30]

The sting

Five meetings took place[30] between the RIRA team and the supposed gunrunners in Dublin, Austria and Budapest[19] in which both parties established a working relationship.[27] Phone calls between England, the Irish Republic, Austria and Hungary were tapped and the meetings were bugged.[22] The Daily Telegraph later reported that O'Farrell and Rafferty told the agents that they had been part of the team which had attacked MI6's headquarters the previous year.[27] Rafferty stated that the organization was held back by its "lack of funds and hardware",[28] telling the agents that "[h]ad we got the proper tools we would have done something more, more worse than that", referring to the RPG attack.[28] McDonald suggested they "could do better with more advanced kit",[27] telling the agents that what they would do with it would "bring a smile to your face".[31]

Richard Barrett and Tom Parker, 2018

Two[36] MI5 agents of Middle Eastern appearance arranged to meet the trio in an Arab restaurant[27] in Piešťany,[19] western Slovakia,[2] a spa town which had had a large Arabian community since the 1970s.[30][22][note 5] The Guardian noted that it popular not only with wealthy Arabs, but also with ex-KGB arms dealers.[9] Afraid of being overheard, the Irishmen presented their list of requests to the MI5 men written on a restaurant napkin.[28][1] McDonald did not intend to let the agents keep the list, but one of them forestalled his attempts to retrieve it by taking it from the table, pretending to blow his nose on it and subsequently pocketing the napkin.[27][28]

Warrants had been issued under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, reported The Daily Telegraph, "relating to the illegal membership of a proscribed organisation, entering into arrangements for the purposes of terrorism, fundraising for the purposes of terrorism and conspiracy charges".[12] The three were arrested on Thursday[12] 5 July 2001[37] by Slovak police[38] implementing the British warrants[29] and in expectation of an extradition request,[39] since the UK has an extradition treaty with Slovakia.[12] The chief of Slovak Interpol compared the arrests to a scene "just like you see in films",[1] as Slovak commandos had set up roadblocks which they used to force the Irishmen's car off the road and ambush them. "All three were taken down in a matter of seconds", he said.[1]

Slovak Chief Prosecutor Milan Hanzel did not acknowledge that the men were IRA militants for a week. Following questioning in Bratislava,[39] they were imprisoned in Trnava on an international arrest warrant.[22] Their names were not publicly released for more than a week.[39] While in Slovak custody, according to El Mundo, the three confessed to having met with Osama bin Laden's European finance manager, Hamid Aich.[note 6] Additionally, The Slovak Spectator reported, they received a large amount of money from him, which was "to be deposited in banks in Santander, Bilbao and Vitori, likely to be used by the Spanish terrorist organisation ETA".[17] Interior Minister Ivan Šimko denied any knowledge of the possibility, but also admitted that even if he did, he would not have answered.[17]

Extradition

Slovakia agreed to extradite the three to England in August 2001,[39] although only after a lengthy legal dispute.[40] The men's Slovak lawyer, Jan Gereg,[41] argued that their rights had been violated while in Slovak custody. There had been insufficient time, the legal team argued, for the court to reach an independent decision on the extradition request, and further that the court which examined the request was too minor to make such a decision. Gereg said, ""Even when you're dealing with the worst kind of terrorist, you have to keep to at least the basic principles of law".[1] Their solicitors also claimed that MI5 had illegally used covert surveillance devices, including bugs and hidden cameras. The Slovak court denied their appeal and allowed the extraditions to go ahead;[1][1][22] Alica Klimesova, a justice ministry spokesperson, stated: "the court ruled that the extradition of the three is legally acceptable, and now only the minister will decide".[41] The men were flown to London on 30 August 2001.[42]

On arrival in the UK, the three were held at a "central London police station", and then in November appeared at Old Bailey Number Two Court, under an armed guard, for arraignment.[43] Their trial was set for April 2002 and was expected to last between six to eight weeks. While in police custody, the three men confessed to attempting to purchase arms for use in terrorist attacks.[16] Gardaí searched their homes in Dundalk but did not arrest anyone as a result,.[2]

Reactions

The 32CSM accused those involved in the peace process of having a "sinister agenda"[44] regarding other Republicans, and announced a campaign for the three men's immediate release.[44] Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble "welcomed" the arrests. He suggested it could indicate the start of a period of increased cooperation between the UK and Eastern Europe, although he also stated that "there has been a delay or a reluctance in the past by the Irish authorities to move against" dissident Republicans.[44] The Slovak government. meanwhile, announced that in the wake of the joint operation, "if we ever had such a reputation [for gunrunning] such events [as the arrest of the Irishmen] help to make that a thing of the past".[1]

Sentencing and imprisonment

Kathy Donaghy and Clodagh Sheehy , 2001

McDonald, Rafferty and O'Farrell stood trial at Woolwich Crown Court[22] in May 2002.[31] They were not expected to plead; usually Irish Republicans, when on trial in British courts, refuse to recognise the court's jurisdiction and ignore the proceedings.[27] However, on this occasion, not only did they plead, but they pleaded guilty—possibly the first time this had happened in the course of The Troubles.[27][28][note 7] Rafferty's counsel called it a "momentous" occasion and said that, on their behalf, he urged the Judge to sentence the men as soon as possible; they were, he said, "extremely anxious now to know their fate".[22] The judge acknowledged that they may have been "pressures upon you coming from the accident of where you lived and loyalty to those you know",[28] but said this was outweighed by the severity of what they had intended to do.[28] The three pled guilty to various charges under the Terrorism Act 2000 and conspiracy to cause explosions.[46] They also claimed to have been planning to bomb either Ireland or London on their successful return.[1] Friends and relatives of the accused were in the public gallery.[47] They were sentenced on 7 May[1] to 30 years' imprisonment each.[20] The 32CSM announced that it was "shocked by the length of the sentence, considering the three men had changed their pleas to guilty just before the trial was due to start".[47]

While serving their sentences in England, they were held in HM Prison Belmarsh; the Irish Republican Prisoners' Welfare Association protested the conditions they claimed the men were being held under.[1] The IRPWA claimed that the men were "confined to their cells for 26 hours at a time they are not allowed any exercise periods, use of the gym is also proscribed—as are visits to the prison shop and library. As a result, all three men are suffering physically with serious weight-loss".[1]

The three men appealed against their sentences in July 2005. One of their solicitors, Julian Knowles, accused the British government of "bypass[ing] fundamental legal principles"[40] in order to secure their extradition from Slovakia, and thus, that their extradition had been illegal.[40] Another counsel, Ben Emmerson, described the original sentences as "manifestly excessive"[48] because the trio were only "foot soldiers".[48] Emmerson also reminded the court that, in Ireland, Michael McKevitt had recently been convicted of leading the Real IRA, but was only sentenced to 20 years. Although Emmerson stopped short of accusing MI5 of entrapment, he did suggest that it was a "ruse conducted in the public interest",[48] and called the prosecution of the Slovak Three an "abuse of process".[48] News outlets at the time suggested that if the appeal had succeeded, it could have impacted on the ability of MI5 to perform such sting operations in the future.[40] However, the Court of Appeal refused to overturn their convictions, instead reducing each man's sentence by two years[48] on account of their original guilty pleas.[49] According to Lord Justice Hooper, the court reduced the sentences "not without some reluctance".[48] In 2006, the three prisoners were transferred, under the Transfer of Sentenced Persons Acts,[50] to Portlaoise Prison, in County Laois, to complete their sentences in Ireland.[20]

Aftermath

Operation Samnite was the first operation by MI5—officially a domestic intelligence service—to be based solely on evidence gathered abroad.[19] It has since been described as illustrating the advantages of close cooperation between national security agencies.[33] It was also in stark contrast to previous operations MI5 had attempted, some of which have been described as "too cavalier" in their approach.[27]

Release

In July 2014 the three men instructed their solicitors to challenge the legality of their sentencing and continued detention.[38][note 8] In September that year Judge Gerard Hogan ordered the immediate release of O'Farrell, Rafferty and McDonald:[20]

After finding the High Court had no jurisdiction to retrospectively adapt, so as to achieve compatibility with Irish law, the defective warrants under which the three were detained here following their transfer from English prisons in 2006.[20]

The men's relatives were in court to hear the ruling; they were freed within hours of his announcement[38] on the evening of 11 September 2014,[46] having served 12 years of their 28-year sentence.[50] The State appealed both the decision and the men's immediate release, in an attempt to keep them imprisoned until October 2016.[20] The appeal was held that year. The Supreme Court upheld Hogan's ruling by a majority of 4/3.[note 9] Although the judgment noted that it was a "troubling case", and even that "many would say, having committed these very serious crimes" the three should be made to serve every year of their imposed sentences, the procedure by which they had had their sentences transferred had been "fundamentally defective" and incompatible with Irish law as it then stood. The warrants were, it concluded, void ab initio. Further, they stated that the legal deficiencies were beyond mend either by the law as it stood or by the Irish courts.[20] The disputing judges had disagreed on this last point, believing that it was legally possible to adjust the warrants after the fact; the judgment placed responsibility for resolving potential disparity with the sentencing guidelines of another state with the sentencing state, in this case, England.[20] The fundamental discrepancy was that under English law, any prisoner serving a custodial sentence of between one and 50 years automatically qualifies for release after serving two-thirds of the sentence. Irish law, on the other hand, only allows for 25% remission[20] and no release on licence.[46] As such, had the trio remained in England, they would have been liable to release after 18 years. Further, not only did the warrants themselves record an incorrect sentence (28, rather than 30 years), but the sentence itself did not exist in Irish sentencing guidelines: conspiracy, while carrying a 20-year penalty in England, has a maximum term of 20 years in Ireland.[20]

As a result of the disparity revealed by the 2016 appeal decision, the Irish government ceased processing application requests from Irish prisoners in foreign prisons. In April 2018, the Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan confirmed that there were 36 outstanding requests awaiting consideration, and another five had been released. Flanagan confirmed that the High Court's ruling was directly responsible for the delay,[52] saying that all such future releases were "on hold"[51] while the implications of the three men's release were considered and the possibility of adjusting the law was weighed.[51] The Irish Council for Prisoners Overseas, however, complained that this left prisoners in a legal "limbo".[52]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The moniker "Slovak three" was originally bestowed upon the men by the Irish Republican Prisoners' Welfare Association, a support group for imprisoned RIRA men and their families.[1]

- ↑ Terrorism itself, for example, was not made illegal in Slovakia until after the 11 September attacks,[15] and a Slovak government agent commented anonymously that "the world looks very negatively on the fact that our arms traders falsify licenses and end-user certificates and are supplying global terrorists with weapons and systems" and that Slovakia was "a high-risk country from the viewpoint of trading in arms".[16] Czechoslovakia was one of the busiest weapons producers of the Warsaw Pact, and the fall of communism led to weapons factories closing. Those that continued to produce weapons paid sufficiently low wages as to make staff susceptible to bribery.[17] The Slovak Spectator reported that within a few years, military production had declined by 90% and 50,000-60,000 people previously employed in the arms-manufacturing industry had lost their jobs.[18]

- ↑ This was an attempt to have a similar source of weapons and money that the Provisionals had found in Colonel Gadaffi's Libya. Gadaffi had, however, by now entered into a "cautious rapprochement with the West".[22]

- ↑ For context, reported a Slovakian news agency, the usual amount of semtex required for a car bomb was around 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb).[30]

- ↑ The Slovak Spectator described Piešťany thus: "The spa town of Piešťany has long been a European health retreat for wealthy Arabs. Under the former communist regime, middle-east oil magnates and sheikhs would come to the town for its special health centres and natural springs. An Arab influence has remained in the town, and hotels in Piešťany receive Arab TV stations, including TV Kuwait."[17]

- ↑ According to the The Slovak Spectator, Aich, who resided in Dublin at the time, had founded the Agency for Mercy and Sympathy, which security services suspected of being the financial hub of 22 global terrorist organisations.[17]

- ↑ A side-effect of the trio's guilty pleas was that a covert tape recording of Michael McKevitt in conversation that was due to be played to the court was never heard, and would not be until McKevitt himself was on trial for directing acts of terrorism the following year.[45]

- ↑ This followed what was called the Sweeney case[51]—officially Sweeney v. Governor of Loughan House Open Centre IESC 42[50]—in 2015. Irishman Vincent Sweeney had received 16 years imprisonment in Britain in 2006 and was transferred to Ireland two years later. He then challenged the grounds of his continued imprisonment in Ireland, claiming he should be released. Although his appeal to the High Court failed, his subsequent appeal to the Supreme Court succeeded and he was released the same day. Sweeney's case set the precedent for the Slovak Three's successful appeal,[51] because "Judge Hogan "appl[ied] the principles identified in Sweeney".[50]

- ↑ In the majority were Justices William McKechnie, John MacMenamin, Mary Laffoy, Iseult O'Malley; supporting the State's appeal were the Chief Justice Susan Denham, Frank Clarke and Donal O'Donnell.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Nicholson 2002a.

- 1 2 3 4 Donaghy & Sheehy 2001.

- ↑ Harnden 1999, pp. 429–431.

- ↑ English 2003, p. 296.

- ↑ Mooney & O'Toole 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ Mooney & O'Toole 2004, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Mooney & O'Toole 2004, p. 47.

- 1 2 Boyne 1996, pp. 382–383.

- 1 2 Norton-Taylor 2001.

- ↑ Mooney & O'Toole 2004, p. 321.

- ↑ Boyne 1996, pp. 382,440.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cracknell & Murray 2001.

- ↑ Boyne 1996, p. 384.

- 1 2 Holt 2001.

- ↑ USDS 2004, p. 53.

- 1 2 HRW 2004, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Holt 2001b.

- ↑ Nicholson 2002b.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barrett & Parker 2018, p. 244.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Carolan 2016.

- ↑ Tonge 2012, p. 464.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Millward 2002.

- ↑ BBC News 2001b.

- ↑ Staff writer 2000.

- ↑ BBC Home 2001.

- ↑ Beurkle 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Johnston 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Norton-Taylor 2002.

- 1 2 3 Staff writer 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Petrovič & Wáclav 2018.

- 1 2 3 Steele 2002.

- ↑ Medvecký & Sivoš 2016, p. 344.

- 1 2 Parker 2010, p. 28.

- 1 2 Richards 2007, p. 89.

- ↑ Harris et al. 2001.

- ↑ LMFN 2014.

- ↑ Holt 2001, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Carolan 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 BBC News 2001a.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff writer 2005.

- 1 2 RTÉ 2001.

- ↑ Hopkins 2001.

- ↑ Evening Standard 2001.

- 1 2 3 Edwards 2013, p. 131.

- ↑ Henry & Erwin 2008.

- 1 2 3 O'Faolain 2014.

- 1 2 RTÉ 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Irish Times 2005.

- ↑ BBC News 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Connolly 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Russell 2015.

- 1 2 McCárthaigh 2018.

Bibliography

- Barrett, R.; Parker, P. (2018). "Acting Ethically in the Shadows: Intelligence Gathering and Human Rights". In Nowak M. Using Human Rights to Counter Terrorism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 236–265. ISBN 978-1-784715-27-4.

- BBC Home (3 August 2001). "2001: Car bomb in west London injures seven". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2001.

- BBC News (6 July 2001a). "Slovakia confirms 'republican' arrests". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- BBC News (4 March 2001b). "Bomb blast outside BBC". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- BBC News (15 July 2005). "Real IRA men have terms reduced". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Beurkle, T. (22 September 2000). "Attack on MI6 Snarls Central London: Missile Hits the Home of British Intelligence". The New York Times. OCLC 960428092. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Boyne, S. (1996). "The Real IRA: after Omagh, what now?". Jane's Intelligence Review. OCLC 265523367.

- Carolan, M. (11 September 2014). "Judge directs immediate release of three dissident republicans". The Irish Times. OCLC 740962663. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Carolan, M. (12 July 2016). "State loses appeal against release of dissident republicans". The Irish Times. OCLC 740962663. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Connolly, R. (14 July 2016). "Supreme Court rules against the State in appeal over the release of dissident republicans". Irish Legal News. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Cracknell, D.; Murray, A. (8 July 2001). "Three men held in Slovakia over IRA gunrunning". The Daily Telegraph. OCLC 14995167. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Donaghy, K.; Sheehy, C. (10 August 2001). "RIRA suspects face extradition from Slovakia". The Irish Independent. OCLC 18699751. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Edwards, R. D. (2013). Aftermath: The Omagh Bombing and the Families' Pursuit of Justice. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-44648-578-1.

- English, R. (2003). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-33049-388-8.

- Evening Standard (12 November 2001). "'Real IRA'men come to court". Evening Standard. OCLC 55942689. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Harnden, T. (1999). Bandit Country. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-34071-736-3.

- Harris, P.; McDonald, H.; Thompson, T.; Bright, M. (5 August 2001). "The Irish Traveller with a chilling taste for terror". The Observer. OCLC 302341888. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Henry, L.; Erwin, A. (3 October 2008). "Court may hear tape of Real IRA chief". The Belfast Telegraph. OCLC 725218560. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Holt, E. (19 October 2001). "POLITICS-SLOVAKIA: New Laws to Tighten Flows of Money and Arms". IPS. Inter-Press Service. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Holt, E. (22 October 2001b). "Bio-terrorism panic hits Slovakia". The Slovak Spectator. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Hopkins, N. (31 Aug 2001). "Real IRA suspects extradited from Slovakia guns deal" (The Guardian). OCLC 614761493. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- HRW (2004). "Stemming Slovakia's Ams Trade with Human Rights Abusers". Human Rights Watch. 16. OCLC 150343575.

- Johnston, P. (3 May 2002). "Tip-off that set up Real IRA 'Arab sting'". The Daily Telegraph. OCLC 14995167. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- LMFN (12 September 2014). ""Slovakia Three" freed from prison after High Court ruling". Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- McCárthaigh, S. (11 April 2018). "Irish inmates abroad 'left in limbo' by transfer system". The Times. OCLC 34539152. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Medvecký, M.; Sivoš, J. (2016). "Slovakia: State Security and Intelligence Since 1945". In de Graaff, B.; Nyce, J. M. Handbook of European Intelligence Cultures. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 335–346. ISBN 978-1-44224-942-4.

- Millward, D. (3 May 2002). "Irish terrorists admit bomb plot after falling into MI5 trap". The Telegraph. OCLC 14995167. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Norton-Taylor, R. (16 Jul 2001). "MI5 posed as Iraqi arms dealers to snare Real IRA". The Guardian. OCLC 614761493. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Norton-Taylor, R. (8 May 2002). "30 years in jail for Real IRA trio". The Guardian. OCLC 614761493. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- O'Faolain, A. (23 September 2014). "RIRA trio go free due to flawed arrest warrants". The Irish Independent. OCLC 18699751. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Mooney, J.; O'Toole, M. (2004). Black Operations: The Secret War Against the Real IRA. London: Maverick House. ISBN 978-0-95429-459-5.

- Nicholson, T. (13 May 2002a). "Real IRA's 'Slovak three' get 30 years each". The Slovak Spectator. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Nicholson, T, (28 October 2002b). "From cheerleader to referee: The state and Slovak arms exports, 1993-2002". The Slovak Spectator. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Parker, T. (2010). "United Kingdom: Once More Unto the Breach". In Schmitt G. J. Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism: American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism. Washington, DC: AEI Press. pp. 8–31. ISBN 978-0-84474-350-9.

- Petrovič, J.; Wáclav, P. (24 January 2018). "Slovensko na mape teroristov: ako sme pomohli zadržať členov Pravej IRA". Aktuality.sk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Richards, A. (2007). "The Domestic Threat: The Cases of Northern Ireland and Animal Rights Extremism". In Wilkinson P. Homeland Security in the UK: Future Preparedness for Terrorist Attack since 9/11. London: Routledge. p. 89114. ISBN 978-1-13417-609-0.

- RTÉ (7 May 2002). "Men jailed for Real IRA arms offences". RTÉ News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- RTÉ (9 Aug 2001). "Slovak court rules extradition is legal". RTÉ. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Russell, C. (4 May 2015). "Prisoners using loophole to get out of jail early". The Journal. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Staff writer (1 June 2000). "Bomb explodes on Hammersmith bridge". The Guardian. OCLC 614761493. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Staff writer (7 July 2001). "International fight against `Real IRA' is stepped up". The Irish Times. OCLC 34539152. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Staff writer (13 July 2005). "Extradition of Real IRA activists 'bypassed legal codes'". The Irish Independent. OCLC 18699751. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Steele, J. (8 May 2002). "Real IRA men snared by MI5 given 30 years". The Daily Telegraph. OCLC 14995167. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- The Irish Times (16 July 2005). "'Real IRA' men's sentence cut in London appeal" (The Irish Times). OCLC 34539152. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Tonge, J. (2012). ""They Haven't Gone Away You Know": Irish republican "Dissidents"t and "Armed Struggle"". In Horgan, H.; Braddock, K. Terrorism Studies: A Reader. London: Routledge. pp. 454–468. ISBN 978-0-41545-504-6.

- USDS (2004). Patterns of Global Terrorism. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State. OCLC 54055955.