Slovak–Hungarian War

| Slovak-Hungarian Border War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Interwar period | |||||||||

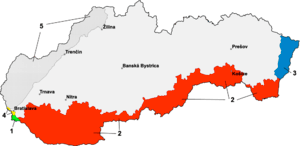

Territorial changes of Slovakia: land ceded to Hungary before (red) and after (blue) the war (Carpatho-Ukraine not shown) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Jozef Tiso Augustín Malár |

Miklós Horthy András Littay | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

3 infantry regiments 2 artillery regiments 9 armoured cars 3 tanks |

5 infantry battalions 2 cavalry battalions 1 motorized battalion 3 armoured cars 70 tankettes 5 light tanks | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Slovak military: 22 killed, 360 Slovak and 311 Czech POW 9 Avia B534 destroyed or damaged Slovak civilians: 36 killed |

Hungarian military: 8 killed, 30 wounded Several vehicles and artillery pieces destroyed 1 Fiat CR.32 shot down Hungarian civilians: 15 killed | ||||||||

The Slovak–Hungarian War, or Little War (Hungarian: Kis háború, Slovak: Malá vojna), was a war fought from 23 March to 31 March 1939 between the First Slovak Republic and Hungary in eastern Slovakia.

Prelude

After the Munich Pact, which weakened Czech lands to the west, Hungarian forces remained poised threateningly on the Slovak border. They reportedly had artillery ammunition for only 36 hours of operations, and were clearly engaged in a bluff, but it was one that Germany had encouraged, and one that they would have been obliged to support militarily if the much larger and better equipped Czechoslovak Army chose to fight. The Czechoslovak army had built 2,000 small concrete emplacements along the border wherever there was no major river obstacle.

The Hungarian Minister of the Interior, Miklós Kozma, had been born in Carpathian Ruthenia, and in mid-1938 his ministry armed the Rongyos Gárda ("Ragged Guard"), which began to infiltrate into southern Slovakia and Carpatho-Ukraine. The situation was now verging on open war. From the German and Italian points of view, this would be premature, so they pressured the Czechoslovak government to accept their joint Arbitration of Vienna. On 2 November 1938 this found largely in favour of Hungary and obliged Czechoslovakia to cede to Hungary 11,833 km² of the south part of Slovakia, which was mostly Hungarian-populated (according to the not objective 1910 census[2]). The partition also cost Slovakia Košice, its second largest city, and left the capital, Bratislava, vulnerable to further Hungarian pressure.

The First Vienna Award did not fully satisfy Hungary, so this was followed by 22 border clashes between 2 November 1938 and 12 January 1939.

In March 1939, a new crisis hit the political scene in Czechoslovakia. President of Czechoslovakia Emil Hácha dismissed the Slovak government of Jozef Tiso and appointed a new Slovak prime-minister Karol Sidor. Hitler decided to take advantage of the situation and inflict a final blow to the weakened Czechoslovak state. His emissary approached Sidor with the goal to divide Czechs and Slovaks to make the final blow easier. Hitler made it absolutely clear that either Slovakia would declare independence immediately and place itself under Nazi Germany's "protection" or he would let Hungary, whose forces were – reported by Ribbentrop – gathering on the border, to take over even more land. However, Sidor refused the coercion and what would be considered treason. Hitler then asked the dismissed prime-minister Tiso. On the evening of 13 March 1939, Tiso and Ferdinand Ďurčanský met Hitler, von Ribbentrop, and Generals Walther von Brauchitsch and Wilhelm Keitel in Berlin. During this time, being aware of the German position, Hungary was preparing for action on the adjacent Ruthenian border.

During the afternoon and night of 14 March, the parliament of Slovakia proclaimed Slovakia's independence from Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovak president Hácha, in an attempt to save the country, travelled to Berlin to persuade Hitler not to intervene in Czechoslovak affairs. Instead, Hitler made him to surrender the army and accept the occupation. At 5:00 am on March 15 Hitler declared that the unrest in Czechoslovakia was a threat to German security, sending his troops into Bohemia and Moravia, which gave virtually no resistance.

Slovakia was surprised when Hungary recognized its new state as early as 15 March. However, Hungary was not satisfied with their frontier with Slovakia and, according to Slovak sources, weak elements of their 20th Infantry Regiment and frontier Guards had to repulse a Hungarian attempt to seize Hill 212.9 opposite Uzhhorod (Ungvar). In this and the subsequent shelling and bombing of the border villages of Nižné Nemecké and Vyšné Nemecké, Slovakia claimed to have suffered 13 dead, and it promptly petitioned Germany, invoking Hitler's promise of protection.

On 17 March, the Hungarian Foreign Ministry told Germany that Hungary wanted to negotiate with the Slovaks over the eastern Slovak boundary on the pretext that the existing line was only an internal Czechoslovak administrative division, not a recognized international boundary, and therefore needed defining now that Carpatho-Ukraine had passed to Hungary. It enclosed a map of their proposal that shifted the frontier about 10 km (6 mi) west of Uzhhorod, beyond Sobrance, and then ran almost due north to the Polish border.

The Hungarian claim partly relied on the 1910 census, which stated that Hungarians and Ruthenians, not Slovaks, formed the majority in north-eastern Slovakia. In addition to the demographic issue, Hungary also had another purpose in mind: protecting Uzhhorod and the key railway to Poland up the Uzh River, which was within view of the current Slovak border. Therefore it resolved to push the frontier back a safe distance beyond the western watershed of the Uzh Valley.

Germany let Hungary know that it would acquiesce to such a border revision and told Bratislava so. On 18 March, the Slovak leaders, in Vienna for the signing of the Treaty of Protection, were forced to accept this, though grudgingly, and Bratislava ordered Slovak civil and military authorities to pull back. All other potential Hungarian requests were supposed to be illegal in Slovakia.

Hungary was aware that Slovakia had signed a treaty guaranteeing Slovakia's borders on 18 March and that it would come into force when Germany countersigned it. It, therefore, decided to act immediately and take advantage of the disorganized Slovak army, which had not yet fully consolidated. Thus, their forces in the western Carpatho-Ukraine began to advance from the River Uzh into eastern Slovakia at dawn on 23 March, some six hours before Joachim von Ribbentrop countersigned the Treaty of Protection in Berlin.

Order of battle

War

Land war

At dawn on 23 March 1939 Hungary suddenly attacked Slovakia from Carpatho-Ukraine with instructions being to "proceed as far to the west as possible". Hungary attacked Slovakia without any declaration of war, catching the Slovak army unprepared because many Slovak soldiers were in transit from the Czech region and had not reached their Slovak units yet. Czech soldiers were leaving newly established Slovakia, but many of them decided to support their former units in Slovakia after the Hungarian attack.

In the north, opposite Stakčín, Major Matějka assembled an infantry battalion and two artillery batteries. In the south, around Michalovce, Štefan Haššík, a reserve officer and a local Slovak People's Party secretary, gathered a group of about four infantry battalions and several artillery batteries. Further west, opposite the passive, but threatening Košice – Prešov front where Hungary maintained an infantry brigade, Major Šivica assembled a third Slovak concentration. To the rear, a cavalry group and some tanks were thrown together at Martin, and artillery detachments readied at Banská Bystrica, Trenčin and Bratislava. However, German interference disrupted or paralysed their movement, especially in the V Corps. The Slovak defence was tied down, as the Hungarian annexations the last autumn had transferred the only railway line to Michalovce and Humenné to Hungary, thereby delaying all Slovak reinforcements.

Hungarian troops advanced quickly into eastern Slovakia, which surprised both Slovakia and Germany. Despite the confusion caused by the hurried mobilization and acute shortage of officers, the Slovak force in Michalovce had coalesced enough to attempt a counter-attack by the next day. This was largely due to a Czech Major Kubíček, who had taken over command from Haššik and begun to get a better grip on the situation. Because they were based on a widely available civilian truck, spares were soon found to repair five of the sabotaged OA vz. 30 armoured cars in Prešov, and they reached Michalovce at 05:30 on 24 March. Their Czech crews had been replaced by scratch teams of Slovak signallers from other technical armed forces. They were immediately sent to reconnoitre Budkovce, some 15 km (9 mi) south of Michalovce, but could not find any trace of the Hungarians.

The Slovaks decided to counter-attack eastwards where the most advanced Hungarian outpost was known to be some 10 km (6 mi) away at Závadka. The road-bound armoured cars engaged the Hungarian pocket from the front whilst Slovak infantry worked round their flanks. Soon they forced the heavily outnumbered Hungarians to fall back from Závadka towards their main line on the River Okna/Akna, just in front of Nižná Rybnica.

The armoured cars continued down the road a little past Závadka whilst the Slovak infantry fanned out and began to deploy on a front of some 4 km (2.5 mi) on either side of them, between the villages of Úbrež and Vyšné Revištia. The infantry first came under Hungarian artillery fire during the occupation of Ubrež, north of the road. At 23:00 a general attack was launched on the main Hungarian line at Nižná Rybnica. The Hungarian response was fierce and effective. The Slovaks had advanced across open ground to within a kilometre of the Akna River when they began taking fire by Hungarian field and anti-tank artillery.

One armoured car was hit in the engine and had to be withdrawn, while a second was knocked out in the middle of the road by a 37mm anti-tank cannon. The raw infantry, unfamiliar with their new officers, first went to ground and then began to retreat, which soon turned into a panic that for some could not be stopped before Michalovce, 15 km (9.3 mi) to the rear. The armoured cars covered the retreating infantry with their machine guns to forestall any possible Hungarian pursuit.

Late on 24 March, four more OA vz.30 armoured cars and three LT vz.35 light tanks and a 37mm anti-tank cannon arrived in Michalovce from Martin to find total confusion. Early on 25 March they headed eastwards, sometimes steadying the retreating infantry by firing over their heads, thereby ensuring the reoccupation of everywhere up to the old Úbrež – Vyšné Revištia line, which the Hungarians had not occupied. However, the anti-tank section mistakenly drove past the knocked-out armoured car and ran straight into the Hungarian line, where it was captured.

By now, elements of the 41st Infantry Regiment and a battery of 202nd Mountain Artillery Regiment had begun to reach Michalovce, and Kubíček planned a major counter-attack for noon, to be spearheaded by the newly arrived tanks and armoured cars. However, German pressure brought about a ceasefire before it could go in. On 26 March, the rest of 202nd Mountain Artillery Regiment and parts of the 7th and 17th Infantry Regiments began to arrive. There were now some 15,000 Slovak troops in and around Michalovce but, even with these reinforcements, a second counter-attack had little better prospect of success than the first, because the more numerous and cohesive Hungarians were well dug-in and had more than enough 37mm anti-tank cannons to deal effectively with the three modern light tanks that represented the only, slight, advantage possessed by the Slovaks.

Air war

Slovak Air Force

After the splitting of Czechoslovakia, the six regiments of the former Czechoslovak Air Force were also divided. The core of this air force on Slovak territory was the 3rd Air Regiment of Milan Rastislav Štefánik, which came under Slovak Ministry of Defence control. However, most of the officers, experienced pilots and aviation experts were Czechs.

Before 14 March, the Slovak Air Force (Slovenské vzdušné zbrane) had about 1,400 members. After the split, Czechoslovakia had only 824 left.[3] Returning crews from occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia only slowly reinforced the nascent Slovak Air Force. The tactical situation was most critical in eastern Slovakia, at the airport of Spišská Nová Ves. The two fighter squadrons at that airport only had nine pilots, and there were only three officers at the airport headquarters. Additionally, the situation was becoming more and more critical as Hungarian attacks were increasing.[3] Many pilots flying together in those days were collected from different parts of Slovakia and had no time to train together, which put them at a marked disadvantage against the prepared and complete Hungarian squadrons.

The best Slovak fighter plane of the time was the Czech Avia B-534.

Occupation of Spišská Nová Ves airport at 22 March 1939:[3]

| Squadron | Planes | Crew |

|---|---|---|

| 49th (fighters), part of II/3 wing | 10 × Avia B-534 | 5 pilots |

| 12th (patrols), part of II/3 wing | 5 × Aero Ap.32, 5 × Letov Š-328 | 9 pilots, 6 sentries |

| 13th (patrols), part of II/3 wing | 10 × Letov Š-328 | |

| 45th (fighters), part of III/3 wing | 10 × Avia B-534 | 7 pilots |

Other elements of the 3rd Air Regiment of Milan Rastislav Štefánik were at airfields in Vajnory, Piešťany, Nitra, Žilina and Tri Duby. However, a lack of pilots greatly hampered its effectiveness. Some crews from Piešťany and Žilina were sent to support Spišská Nová Ves. In this state, the Slovak Air Force had to support ground units in combat and interfere with Hungarian supplies. To do this, they had to fly low and, as they had no armour, become an easy target for Hungarian artillery or even ground unit soldiers.

Royal Hungarian Air Force

Hungary concentrated its aerial assets on targets in eastern Slovakia:[4]

| Unit | Planes | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1/1 vadászszázad (fighters) | 9 × Fiat CR.32 | Ungvár / Uzhhorod |

| 1/2 vadászszázad (fighters) | 9 × CR.32 | Miskolc |

| 1/3 vadászszázad (fighters) | 9 × CR.32 | Csap / Chop |

| 3/3 bombázószázad (bombers) | 6 × Ju-86K-2 | Debrecen |

| 3/4 bombázószázad (bombers) | 6 × Ju-86K-2 | Debrecen |

| 3/5 bombázószázad (bombers) | 6 × Ju-86K-2 | Debrecen |

| VII felderítőszázad (patrols) | 9 × WM-21 | Miskolc |

| VI felderítőszázad (patrols) | 9 × WM-21 | Debrecen |

The best plane in the Royal Hungarian Air Force was the Fiat CR.32 fighter. It did not have as powerful an engine as the Slovak-operated Avia, so Hungarian pilots tried to fight at horizontal levels, while the Slovaks tried to take the combat into the vertical plane. The Fiats could be handled better, especially if the Avias were flying with bombs under their wings, making them more clumsy. The Fiat CR.32 had better machine guns.

Combat

On 15 March the Royal Hungarian Air Force did a thorough reconnaissance of eastern Slovakia. The next day Hungarian squadrons were moved to airfields closer to the borders of Slovakia and put on alert.

On the morning of 23 March two Slovak patrol squadrons operating from Spišská Nová Ves searched for the enemy, but ineffectually, as these missions were not yet coordinated with ground units. Later on 23 March Slovak headquarters gave orders for a complete aerial reconnaissance of all areas. Patrols spotted wide movement of Hungarians on Slovak territory. At 13:00 a flight of three Letov Š-328 reconnaissance aircraft was sent to attack the enemy in the area of Ulič, Ubľa, and Veľký Bereznyj. The mission failed when pilots could not positively identify the enemy because of fog. It later turned out that they were Hungarians moving from Ubľa to Kolonica.

After that, another two fighter squadrons of three B-534s were sent on missions. The first discovered Hungarian troops at the railway station in Ulič and destroyed some artillery pieces and other material in an attack. The second, also sent to Ulič, successfully destroyed a few Hungarian vehicles and damaged more equipment, but one plane was shot down and its pilot, Ján Svetlík, killed. Another Slovak squadron was sent to the area, this time to support Slovak ground units. It encountered Hungarian machine gun fire, and another B-534 was shot down. The pilot managed to land, but died a few minutes later. The plane was then destroyed by Slovak soldiers. Two other B-534s attacked Hungarian troops, and, heavily damaged and out of ammunition, returned to Spišská Nová Ves. The last Slovak mission of March 23 consisted of one Š-328, which destroyed an unknown number of Hungarian tanks and vehicles near Sobrance. Its pilot was injured and had to land near Sekčovice. Slovak pilots did not encounter the Hungarian Air Force that day.

In the first day the Slovak Air Force suffered two B-534s destroyed, another four heavily damaged, and two pilots killed. But it had helped slow the Hungarian advance and inflicted significant damage. The next day, the situation rapidly changed.

On the morning of 24 March, one squadron of three B-534s took off to support Slovak units at Vyšné Remety. After reaching the area they were surprised by three Hungarian Fiat CR.32s, and two of the Slovak planes were shot down, with one pilot killed. At 07:00 six B-534s from Piešťany landed in Spišská Nová Ves; three of them then took off to support infantry near Sobrance. Two were shot down, and one Slovak pilot was captured.

Near Michalovce, nine Hungarian fighters shot down three B-534s, which were covering three Letov Š-328s as they bombed Hungarian infantry. One Š-328 was also shot down and the pilot killed. Another had to land because of mechanical problems. From a six-plane formation, only one returned to Spišská Nová Ves.

Bombing of Spišská Nová Ves

On the same day, 24 March, the Royal Hungarian Air Force also bombed Spišská Nová Ves, which was the base of all Slovak air operations. 36 bombers supported by 27 fighters were assigned to the mission, but due to poor organization, faulty navigation, mechanical problems, and last-minute changes, only about 10 bombers actually took part in the attack. Because Slovakia lacked an early-warning system, the Hungarians found the airfield's defences unprepared. Anti-aircraft guns were without crews and ammunition. Most of the Hungarian bombs missed the air operations base, but several hit the airfield, a storage facility, a hangar, a brickworks, and a barracks-yard.[5] Many of the bombs landed in mud and failed to explode.

Although the bombers damaged six planes and several buildings, their mission was not fully successful, as the airfield continued to operate until the end of the conflict.

On 27 March, 13 victims of the bombing – some of them civilians – were buried, arousing intense anti-Hungarian sentiment.

The sole Hungarian Air Force loss of the entire conflict was a Fiat fighter who was accidentally shot down by Hungarian artillery. but the Hungarian Air Force failed to take control of the skies over eastern Slovakia. After the bombing of Spišská Nová Ves, Major Ján Ambruš arrived there on 25 March to organize a revenge air strike on Budapest. The war ended before it could be carried out.

Losses

- Sum total: 807 casualties on both sides, 81 dead (30 military, 51 civilian); 55+ injured (unknown breakdown). 671 POWS (All Czech/Slovak, 46.3% Czech 53.7% Slovak)

- Hungarians: 8 military, 15 civilian dead, 55 injured, no PoWs

- Slovaks: 22 military and 36 civilian dead, unknown injured, 360 Slovak military PoWs + 311 PoWs of Czech (Bohemian and Moravian) origin.

Aftermath

Slovakia had signed a protection treaty with Germany, but Germany violated the treaty by refusing to help the country. Nor did Germany support Slovakia during the Slovak – Hungarian negotiations in early April. As a result, by a treaty signed on 4 April in Budapest, Slovakia was forced to cede to Hungary a strip of eastern Slovak territory (1,697 km², 69,930 inhabitants, 78 municipalities), corresponding today to the area around the towns of Stakčín and Sobrance. The war killed 36 Slovak citizens.

The two sides' claims were contradictory. At the time, Hungary announced the capture of four light tanks and an armoured car. But no Slovak light tanks ever entered action and a medal was awarded to the man who recovered the one knocked-out armoured car from no man's land in the night. On the other hand, there is no doubt that in March the Hungarians did capture at least one LT vz.35 light tank and one OA vz.27 armoured car. The contradictions are attributable to a combination of the fog of war, propaganda and confusion between Hungarian captures in Carpatho-Ukraine and eastern Slovakia.

Slovak casualties are officially recorded as 22 dead – all were named. On 25 March, Hungary announced its own losses as 8 dead and 30 wounded. Two days later it gave a figure of 23 dead and 55 wounded – a total that may include their earlier losses occupying Carpatho-Ukraine. It also reported that it was holding 360 Slovak and 311 Czech prisoners. Many of the Slovaks presumably belonged to the two companies reportedly surprised asleep in the barracks in the first minutes of the invasion. The Czechs were stragglers from the garrison of Carpatho-Ukraine.

Notes

- ↑ A truce was agreed on 24 March, but fighting continued until 31 March.

- ↑ Deák 2002

- 1 2 3 Šipeky, Michal (11 February 2007). "Účasť slovenského letectva vo vojenskom konflikte s Maďarskom 23. marca 1939 – 28. marca 1939". „Malá vojna“ a účasť slovenského letectva v nej (in Czech). Valka.

- ↑ "Druhasvetova". Archived from the original on 24 November 2010.

- ↑ Šipeky, Michal (11 February 2007). ""Malá vojna" a účasť slovenského letectva v nej 3. časť". „Malá vojna“ a účasť slovenského letectva v nej (in Czech). Valka.

Bibliography

- Axworthy, Mark WA (2002). Axis Slovakia – Hitler's Slavic Wedge, 1938–1945. Bayside: Axis Europa Books. ISBN 1-891227-41-6.

- Deák, Ladislav (1993). Malá vojna (in Slovak). Bratislava. ISBN 80-88750-02-4.

- Deák, Ladislav (2002). "Viedenská arbitráž: 2. November 1938". Dokumenty I. Matica slovenská (in Slovak). Martin.

- Niehorster, Dr Leo WG (1998). The Royal Hungarian Army 1920–1945. 1. New York: Axis Europa Books. ISBN 1-891227-19-X.

External links

- "The Slovak-Hungarian Frontier, 1918–1939". Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. – brief overview of the historical context

- Šipeky, Michal (11 February 2007). "Vojenský konflikt". „Malá vojna“ a účasť slovenského letectva v nej (in Czech). Valka.