Skylab 4

The final view of Skylab, from the departing mission 4 crew, with Earth in the background | |

| Operator | NASA |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1973-090A |

| SATCAT no. | 6936 |

| Mission duration | 84 days, 1 hour, 15 minutes, 30 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 55,500,000 kilometers (34,500,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 1214 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Apollo CSM-118 |

| Manufacturer | North American Rockwell |

| Launch mass | 20,847 kilograms (45,960 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 16, 1973, 14:01:23 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn IB SA-208 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS New Orleans |

| Landing date | February 8, 1974, 15:16:53 UTC |

| Landing site | 31°18′N 119°48′W / 31.300°N 119.800°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee | 422 kilometers (262 mi) |

| Apogee | 437 kilometers (272 mi) |

| Inclination | 50.0 degrees |

| Period | 93.11 minutes |

| Epoch | January 21, 1974[1] |

| Docking with Skylab | |

| Docking port | Forward |

| Docking date | November 16, 1973, 21:55:00 UTC |

| Undocking date | February 8, 1974, 02:33:12 UTC |

| Time docked | 83 days, 4 hours, 38 minutes, 12 seconds |

|

Left to right: Carr, Gibson and Pogue Skylab program | |

Skylab 4 (also SL-4 and SLM-3[2]) was the third manned Skylab mission and placed the third and final crew aboard the first American space station.

The mission started on November 16, 1973 with the launch of three astronauts on a Saturn IB rocket from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida and lasted 84 days, one hour and 16 minutes. A total of 6,051 astronaut-utilization hours were tallied by Skylab 4 astronauts performing scientific experiments in the areas of medical activities, solar observations, Earth resources, observation of the Comet Kohoutek and other experiments.

The manned Skylab missions were officially designated Skylab 2, 3, and 4. Mis-communication about the numbering resulted in the mission emblems reading Skylab I, Skylab II, and Skylab 3 respectively.[2][3]

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gerald P. Carr Only spaceflight | |

| Science Pilot | Edward G. Gibson Only spaceflight | |

| Pilot | William R. Pogue Only spaceflight | |

With three rookies, Skylab 4 was the largest all-rookie crew launched by NASA. Following the all rookie Mercury program, there were only five more all-rookie NASA flights -- Gemini 4, Gemini 7, Gemini 8, Skylab 4 and, in 1981, STS-2.

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Vance D. Brand | |

| Science Pilot | William Lenoir | |

| Pilot | Don L. Lind | |

Support crew

Mission parameters

| Mission |

|

|---|---|

| Skylab 2 | 28 |

| Skylab 3 | 60 |

| Skylab 4 | 84 |

- Mass: 20,847 kg (45,960 lb)

- Maximum altitude: 440 km (273 mi) (November 16, 1973)

- Total distance traveled: 34.5 million miles (55,500,000 km)

- Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB

- Epoch: January 21, 1974

- Perigee: 422 km (262 mi)

- Apogee: 437 km (272 mi)

- Inclination: 50.04°

- Period: 93.11 min

Docking

- Docked: November 16, 1973 – 21:55:00 UTC

- Undocked: February 8, 1974 – 02:33:12 UTC

- Time Docked: 83 days, 4 hours, 38 minutes, 12 seconds

Space walks

Gibson and Pogue — EVA 1

- Start: November 22, 1973, 17:42 UTC

- End: November 23, 00:15 UTC

- Duration: 6 hours, 33 minutes

Carr and Pogue — EVA 2

- Start: December 25, 1973, 16:00 UTC

- End: December 25, 23:01 UTC

- Duration: 7 hours, 01 minute

Carr and Gibson — EVA 3

- Start: December 29, 1973, 17:00 UTC

- End: December 29, 20:29 UTC

- Duration: 3 hours, 29 minutes

Carr and Gibson — EVA 4

- Start: February 3, 1974, 15:19 UTC

- End: February 3, 20:38 UTC

- Duration: 5 hours, 19 minutes

Mission highlights

The all-rookie astronaut crew arrived aboard Skylab to find that they had company – three figures dressed in flight suits. Upon closer inspection, they found their companions were three dummies, complete with Skylab 4 mission emblems and name tags which had been left there by Al Bean, Jack Lousma, and Owen Garriott at the end of Skylab 3.[4]

Things got off to a bad start after the crew attempted to hide Pogue's early space sickness from flight surgeons, a fact discovered by mission controllers after downloading onboard voice recordings. Astronaut office chief Alan B. Shepard reprimanded them for this omission, saying they "had made a fairly serious error in judgement."[5]

The crew had problems adjusting to the same workload level as their predecessors when activating the workshop. The crew's initial task of unloading and stowing the thousands of items needed for their lengthy mission also proved to be overwhelming.[6] The schedule for the activation sequence dictated lengthy work periods with a large variety of tasks to be performed, and the crew soon found themselves tired and behind schedule.

Seven days into their mission, a problem developed in the Skylab gyroscopic attitude control system, which threatened to bring an early end to the mission. Skylab depended upon three large gyroscopes, sized so that any two of them could provide sufficient control and maneuver Skylab as desired. The third acted as a backup in the event of failure of one of the others[7]. The gyroscope failure was attributed to insufficient lubrication. Later in the mission, a second gyroscope showed similar problems,[8][9] but special temperature control and load reduction procedures kept the second one operating, and no further problems occurred.

On Thanksgiving Day, Gibson and Pogue accomplished a 6½ hour spacewalk. The first part of their spacewalk was spent deploying experiments and replacing film in the solar observatory. The remainder of the time was used to repair a malfunctioning antenna. During the experience, Gibson remarked, "Boy if this isn't the great outdoors! Inside, you're just looking out through a window. Here, you're right in it."[10] The crew reported that the food was good, but slightly bland. The quantity and type of food consumed was rigidly controlled because of their strict diet. Although the crew would have preferred to use more condiments to enhance the taste of the food, and the amount of salt they could use was restricted for medical purposes, by the third mission the NASA kitchen had increased the availability of condiments, and salt and pepper was in liquid solutions (granular salt and pepper brought aboard by the second crew was little more than "air pollution"). [11]

On December 13, the crew sighted Comet Kohoutek and trained the solar observatory and hand-held cameras on it. They gathered spectra on it using the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph.[12] They continued to photograph it as it approached the Sun. On December 30, as it swept out from behind the Sun, Carr and Gibson spotted it as they were performing a spacewalk.

As Skylab work progressed, the astronauts complained of being pushed too hard, and ground controllers complained they weren't getting enough work done. NASA determined major contributing factors were a large number of new tasks added shortly before launch with little or no training, and searches for equipment out of place on the station.[13][14][15] There was a radio conference to air frustrations[16] which led to the workload schedule being modified, and by the end of their mission the crew had completed even more work than originally planned.

The experiences of the crew and ground controllers provided important lessons in planning subsequent manned spaceflight work schedules. At the same time, in the years following the mission the mistakes and disagreements received added scrutiny. Several writers embellished the more dramatic aspects that led to the radio conference, introducing both “strike” and “mutiny” to the interpretation of events. These and other controversial terms continue to be used, even if inaccurately, to describe the hours leading up to the conference between astronauts and mission control.

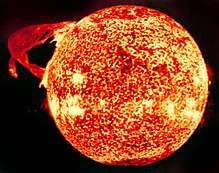

Apart from the controversies, Skylab 4 was noted for several important science contributions. The crew spent many hours studying the Earth. Carr and Pogue alternately manned controls, operating the sensing devices which measured and photographed selected features on the Earth's surface. Gibson and the other crew made solar observations, recording about 75,000 new telescopic images of the Sun. Images were taken in the X-ray, ultraviolet, and visible portions of the spectrum.[13][17]

As the end of their mission drew closer, Gibson continued his watch of the solar surface. On January 21, 1974, an active region on the Sun's surface formed a bright spot which intensified and grew.[13] Gibson quickly began filming the sequence as the bright spot erupted. This film was the first recording from space of the birth of a solar flare.

The crew also photographed the Earth from orbit. Despite instructions not to do so, the crew (perhaps inadvertently) photographed Area 51, causing a minor dispute between various government agencies as to whether the photographs showing this secret facility should be released. In the end, the picture was published along with all others in NASA's Skylab image archive, but remained unnoticed for years.[18]

The Skylab 4 astronauts completed 1,214 Earth orbits and four EVAs totaling 22 hours, 13 minutes. They traveled 34.5 million miles (55,500,000 km) in 84 days, 1 hour and 16 minutes in space. Skylab 4 was the last Skylab mission, the station fell from orbit in 1979.

The three astronauts had joined NASA in the mid-1960s, during the Apollo program, with Pogue and Carr becoming part of the likely crew for the cancelled Apollo 19. Ultimately none of the crew of Skylab 4 flew in space again, as none of the three had been selected for Apollo-Soyuz and all of them retired from NASA before the first Space Shuttle launch. Gibson, who had trained as a scientist-astronaut, resigned from NASA in December 1974 to do research on Skylab solar physics data, as a senior staff scientist with the Aerospace Corp. of Los Angeles, California.

Gallery

Commander Gerald Carr flies a Manned Maneuvering Unit prototype.

Commander Gerald Carr flies a Manned Maneuvering Unit prototype. Carr "balances" Bill Pogue as a demonstration of zero-G.

Carr "balances" Bill Pogue as a demonstration of zero-G. Ed Gibson floats out of the Multiple Docking Adapter connecting the station to the crew's Command Module.

Ed Gibson floats out of the Multiple Docking Adapter connecting the station to the crew's Command Module. Carr and Gibson look through the length of the station from the trash airlock.

Carr and Gibson look through the length of the station from the trash airlock. Carr floats with limbs outstretched to show the effects of zero-G.

Carr floats with limbs outstretched to show the effects of zero-G. The Pogue Seiko, a 'Seiko Automatic-Chronograph' Cal. 6139, the first automatic chronograph in space, used by Bill Pogue.[19][20]

The Pogue Seiko, a 'Seiko Automatic-Chronograph' Cal. 6139, the first automatic chronograph in space, used by Bill Pogue.[19][20] Gibson at the controls of the Apollo Telescope Mount.

Gibson at the controls of the Apollo Telescope Mount. Gibson during an EVA.

Gibson during an EVA.

Spacecraft location

The Skylab 4 command module is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Mission insignia

The triangular emblem features a large number 3 and a rainbow circling three areas of study the astronauts pursued. At the time of the flight, the astronauts issued the following description:

"The symbols in the patch refer to the three major areas of investigation in the mission. The tree represents man's natural environment and refers to the objective of advancing the study of earth resources. The hydrogen atom, as the basic building block of the universe, represents man's exploration of the physical world, his application of knowledge, and his development of technology. Since the sun is composed primarily of hydrogen, the hydrogen symbol also refers to the Solar Physics mission objectives. The human silhouette represents mankind and the human capacity to direct technology with a wisdom tempered by his regard for his natural environment. It also relates to the Skylab medical studies of man himself. The rainbow, adopted from the Biblical story of the Flood, symbolizes the promise that is offered to man. It embraces man and extends to the tree and hydrogen atom, emphasizing man's pivotal role in the conciliation of technology with nature by a humanistic application of our scientific knowledge." Some versions of the patch included a comet in the top curve because of studies made of the comet Kohoutek.

See also

References

- ↑ McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- 1 2 "Skylab Numbering Fiasco". Living in Space. William Pogue Official WebSite. 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ↑ Pogue, William. "Naming Spacecraft: Confusion Reigns". collectSPACE. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Photo-sl3-113-1587". spaceflight.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (November 18, 1973). "Skylab Astronauts Are Reprimanded In 1st Day Aboard". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Astronauts Try to Make Up Time". New York Times. Associated Press. November 19, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "A Skylab Gyroscope Fails, Leaving Only 2 for Control". New York Times. Associated Press. November 24, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Gyro on Skylab Is Erratic; Officials Are Not Alarmed". New York Times. Associated Press. December 8, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Skylab Gyroscope Falters, Puzzling Ground Engineers". New York Times. United Press International. January 4, 1974. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Two Astronauts fix Skylab Antenna". New York Times. Associated Press. November 23, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ http://www.voicesofoklahoma.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Pogue_Transcript.pdf Voices of Oklahoma (2013 pg 33), Wm Pogue

- ↑ "SP-404 Skylab's Astronomy and Space Sciences". Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Canby, Thomas (October 1974). "Skylab, Outpost on the Frontier of Space". National Geographic Magazine. 146: 441–493. :468

- ↑ "Lethargy of Skylab 3 Crew Is Studied". Reuters. December 12, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Skylab Crew Takes Day Off for Rest". New York Times. Associated Press. November 25, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ "Astronauts Debate Work Schedules With Controllers". New York Times. Associated Press. December 31, 1973. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ↑ https://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/gibson-eg.html

- ↑ The Space Review: Secret Apollo published November 26, 2007

- ↑ William Pogue's Seiko 6139 Watch Flown on Board the Skylab 4 Mission, from his Personal Collection... The First Automatic Chronograph to be Worn in Space.

- ↑ The “Colonel Pogue” Seiko 6139, dreamchrono.com.

Further reading

- Gilles Clement, Fundamentals of Space Medicine, Microcosm Press, 2003. pp. 212.

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did was Fly to the Moon. Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 0-9611228-0-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skylab 4. |

- Skylab: Command service module systems handbook, CSM 116 – 119 (PDF) April 1972

- Skylab Saturn 1B flight manual (PDF) September 1972

- NASA Skylab Chronology

- Marshall Space Flight Center Skylab Summary

- Skylab 4 Characteristics SP-4012 NASA HISTORICAL DATA BOOK

- Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident

- Skylab, "The Third Manned Period", NASA History (History.nasa.gov )

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with William Pogue. First person interview conducted with William Pogue on August 8, 2012. Original audio and transcript archived with Voices of Oklahoma oral history project.