Skull Valley Indian Reservation

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

134 enrolled members, 15-20 living on reservation[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Shoshoni language, English | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Mormonism,[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Western Shoshone peoples, Ute people |

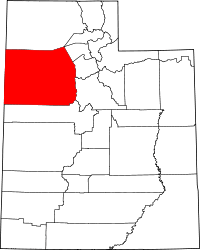

The Skull Valley Indian Reservation is located in Tooele County, Utah, United States, approximately 45 miles (72 km) southwest of Salt Lake City. It is inhabited by the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians of Utah, a federally recognized tribe. The population includes approximately 31 people in 7 households and is characterized by a high incidence of poverty.

Landbase

The reservation comprises 28.187 square miles (73.00 km2) of land in east central Tooele County, adjacent to the southwest side of the Wasatch-Cache National Forest in the Stansbury Mountains. The reservation lies in the south of Skull Valley, with another range, the Cedar Mountains bordering west.

Tribal government

The tribe is governed by a three-person executive committee.[3] A population of 31 persons resided on its territory as of the 2000 census. Tribal membership is 134, with 15 to 20 living on the reservation.[1]

History

On October 12, 1863, the band first signed a treaty with the U.S. federal government. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order established the reservation.[1]

Environmental issues

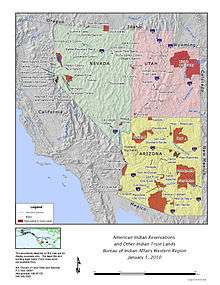

Proximity Issues

With the exception of the west side of the reservation, the immediately surrounding areas have had a long history of being used for external purposes, including: a hazardous waste landfill,[4][5] a nerve gas storage facility that treats some of the most hazardous man-made chemicals,[5] two incinerators for hazardous waste,[4] a magnesium plant that contributes significant amounts of chlorine gas,[4][5][6] and the Intermountain Power Project that releases airborne toxic chemicals.[6] Additionally, the U.S. government has tested biological weapons adjacent to Skull Valley.[5] In general, these proximity issues have an added concern because children make up more than 30% of the tribe.[6] Environmental justice issues have plagued the Goshute Band dating back to at least the 1840s when Mormon settlers would expel lepers to the area in which they lived.[6]

There have been claims that the sum of this colonial expansion of industry into Native American land (common across the country as seen with incident's like the recent Keystone XL Pipeline, and Dakota Access Pipeline) amounts to environmental racism.[6] However, the effects on the Skull Valley Band of the Goshute have not been as well reported as the previously mentioned incidents, as often occurs with smaller native populations with lower levels of political leverage than the larger tribes.[6]

Nevertheless, corporations and various levels of government have provided economic development through all of these nuclear waste sites, incinerators, and other toxic landfills.[6]

Dugway Proving Ground

The United States Army tests the extremely toxic VX nerve agent at their Dugway Proving Ground facility located in the area immediately surrounding the Skull Valley Indian Reservation.[7] The April 12, 1968 Dugway sheep incident, in which 6,000 sheep belonging to Skull Valley Goshute died after exposure to the deadly VX agent being tested at the Proving Ground, occurred on the Reservation.[7] The VX agent operates by inhibiting the body's use of the enzyme cholinesterase, an important controller of nerve function, which in turn prevents the affected person or animal from controlling their bodies leading quickly to death by asphyxiation.[7]

The event occurred during a routine test of a spraying system attached to an F-4 Jet. After successfully hitting the targets at low elevation with 80% of the loaded agent, the plane climbed up to 1,500 feet (460 m) as the remaining agent leaked out of the tanks.[7] It began to rain and snow shortly afterwards, and it is assumed that the precipitation contained the agent, and that when sheep licked up the water and snow they began to show the symptoms of VX poisoning.[8]

The Army has never admitted fault in this incident, though a 1970 report by researchers from the Edgewood Arsenal, indicates that the evidence of nerve gas was incontrovertible.[7] Due to the presence of thousands of sheep carcasses contaminated with the toxic agent, residents of the reservation have been unable to maintain stock on the land since, negatively effecting the economic viability of the reservation's rangeland. It is possible that this has contributed to the tribe's tendency to turn to waste disposal, nuclear storage and other potentially toxic activities as a means for economic development.[6] Dugway and Skull Valley have also been featured in Rage, The Andromeda Strain, Outbreak and Species.

Additionally, the Dugway Proving Ground's experiments with viruses 14 miles (23 km) from the reservation; since the materials produced at this military experiment center are not well known, the future health risks to the residents of the reservation cannot be determined.[6]

Nuclear waste storage debate

The question of the storage of nuclear waste on the reservation is one that divided the tribe for many years.[9][10]

In 1987, the United States Congress created the Office of Nuclear Waste Negotiator in order to facilitate land deals with states, counties, and Native American tribes.[11] In 1991, the first negotiator, David H. Leroy, sent out letters with offers up to millions of dollars to every federally recognized tribe in the country, offering millions of dollars in exchange for contracts permitting the storage of high-level nuclear waste on native land.[11] The Skull Valley Band of Goshutes received a Phase I study grant in 1992 and a Phase II-A grant in 1993; by the later date, the tribe was one of just four tribes that remained interested.[11] Congress eliminated the Office of Nuclear Waste Negotiator in 1994, but a private consortium of utility companies continued to negotiate over nuclear-waste storage deals with the Skull Valley Band and the Mescalero Apaches.[11] In December 1996, Skull Valley Goshute Tribe chairman Leon Bear, signed a preliminary lease on behalf of the tribe with the consortium,[11] providing for the storage of 40,000 tons of nuclear waste at the reservation.[9] The utility companies stated that storage of nuclear waste would be an interim measure until the opening of the planned Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada.[12] However, the Yucca Mountain project was killed due to political opposition, heightening the need for a high-level nuclear waste repository.[12]

The nuclear-waste agreement was a politically controversial issue. Some tribal members supported the $3 billion project[10] for its economic benefits while others (some of whom were members of Ohngo Gaudadeh Devia (OGD), a group of tribal members[6]) were strongly opposed, with some calling it environmental racism.[9][13] Utah's congressional delegation and three successive Utah governors also objected to a nuclear-waste facility in the area,[12][14] Other opponents included group of 71 Indian tribes from across the country; a number of environmentalist groups, including the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, the Sierra Club, and National Environmental Coalition of Native Americans;[3] the anti-nuclear Nuclear Information and Resource Service;[15] and individual activists.[16]

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) approved the lease in March 1997, but the agreement was not in effect as of 2006 "amid a mountain of lawsuits, regulatory hurdles and bitter opposition."[9] In 2006, legislation sponsored by Utah congressman Rob Bishop was signed into law by President George W. Bush, declaring 100,000 acres in the region as wilderness area, thereby cutting off "the only practical route for a rail spur delivering heavy steel casks of spent fuel rods to the Goshute reservation."[14] The legislation was supported by the Secretary of the Air Force;[17] the U.S. Air Force uses Skull Valley as a flight path to the Utah Test and Training Range, and objections were raised to the risks of locating a nuclear-waste site at a location in which an aircraft crash could result in the accidental release of radiation.[14][10]

On safety, the DEIS stated that leakage from casks is highly unlikely, that shipping nuclear waste cargo is no more dangerous than shipping any other cargo, and that the Goshute people of Skull Valley will not be affected disproportionally by the cask container storage facility. However, OGD believes that there could be cumulative impacts from many toxic activities on and near the reservation that could potentially affect the Goshute people.[5]

In 2006, following ten years of review,[12] the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issued a license for the Private Fuel Storage (PFS) project, which the State of Utah challenged in federal court.[14] Subsequently, further development was administratively blocked, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit overturned these obstacles,[12] giving the project a chance at viability.[10] However, the BIA refused to approve lease agreement between the PFS and the Goshute tribune, and U.S. Bureau of Land Management denied an application of a right-of-way that would have been necessary "for offloading the waste and hauling it to the reservation."[10] In December 2012, however, following these renewed obstacles, the project was finally killed as Private Fuel Storage requested the termination of its NRC license.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Skull Valley Band Goshute Tribal Profile". indian.utah.gov. Utah Division of Indian Affairs. Archived from the original on 4 Jun 2013. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017 – via web.archive.org.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- 1 2 Fedarko, Kevin (1 May 2000). "In the Valley of the Shadow". Outside. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Mariah Media. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 Endres, Danielle (15 Oct 2009). "From wasteland to waste site: the role of discourse in nuclear power's environmental injustices". Local Environment. Abingdon-on-Thames, England: Routledge. 14 (10): 917–937. doi:10.1080/13549830903244409.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoffman, Steven M. (1 Dec 2001). "Negotiating Eternity: Energy Policy, Environmental Justice, and the Politics of Nuclear Waste". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 21 (6): 456–472. doi:10.1177/027046760102100604.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hanson, Randel D. (Nov 2001). "An Experiment in (Toxic) Indian Capitalism?: The Skull Valley Goshutes, New Capitalism, and Nuclear Waste". PoLAR. 24 (2): 25–38. doi:10.1525/pol.2001.24.2.25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allen, Dr. Steven J. (4 Mar 2014). "A mighty wind: Nerve gas, six thousand dead sheep, and Soviet trickery". capitalresearch.org. Washington, D.C.: Capital Research Center. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- ↑ El-Attar, L.; Dhaliwal, W.; Howard, C.R.; Bridger, J.C. "Rotavirus Cross-Species Pathogenicity: Molecular Characterization of a Bovine Rotavirus Pathogenic for Pigs" (PDF). Virology. 291 (1): 172–182. doi:10.1006/viro.2001.1222. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Hebert, H. Josef (27 Jun 2006). "Store nuclear waste on reservation? Tribe split: Utah leaders also join battle, seek to block shipments". nbcnews.com. New York: NBCNews.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fahys, Judy (21 Dec 2012). "Utah N-waste site backers call it quits: Environment • Opponents welcome the end of the Skull Valley storage plan". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City: Paul Huntsman. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Radioactive Racism: The History of Targeting Native American Communities with High-Level Atomic Waste Dumps" (PDF). nirs.org. Takoma Park, Maryland: Nuclear Information and Resource Service and Public Citizen (jointly). 2005. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fahys, Judy (1 Dec 2012). "Feds still on the hunt for high-level N-waste storage: Temporary storage • N.M. town clamoring for a facility; Utah may still be in the running". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City: Paul Huntsman. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- ↑ Jim Martin-Schramm,"Skull Valley: Nuclear Waste, Tribal Sovereignty, and Environmental Racism". Journal of Lutheran Ethics. Chicago: Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 5 (10). Oct 2005. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Nuclear waste? Utah says not in our wilderness: Lawmakers get designation as way to stop proposed storage site". nbcnews.com. New York: NBCNews.com. Associated Press. 5 Feb 2006. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- ↑ "Environmental Racism, Tribal Sovereignty and Nuclear Waste". nirs.org. Takoma Park, Maryland: Nuclear Information and Resource Service. 15 Feb 2001.

- ↑ Gilbert, Cathleen (13 Sep 2007). "Public Comment on Draft Environmental Impact Statement dated June 2000" (PDF). nrc.gov. North Bethesda, Maryland: Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

- ↑ "Air Force secretary supports efforts to block Skull Valley waste site". The Daily Herald. Provo, Utah. Associated Press. 8 Dec 2005. p. B7. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skull Valley Indian Reservation. |

- Skull Valley Reservation, Utah, United States Census Bureau

- Skull Valley Band of Goshutes on Facebook