Skomorokh

A skomorokh (скоморох in Russian, скоморохъ in Old East Slavic, скоморaхъ in Church Slavonic) was a medieval East Slavic harlequin, or actor, who could also sing, dance, play musical instruments and compose for oral/musical and dramatic performances. The etymology of the word is not completely clear.[1] There are hypotheses that the word is derived from the Greek σκώμμαρχος (cf. σκῶμμα, "joke"); from the Italian scaramuccia ("joker", cf. English scaramouch); from the Arabic masẋara; and many others.

The skomorokhs appeared in Kievan Rus no later than the mid-11th century, but fresco depictions of skomorokh musicians in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev date to the 11th century.

The Primary Chronicle on skomorokhs concurs with the period. The monk chronicler denounced them as devil servants. Furthermore, the Orthodox Church often railed against them and other elements of popular culture as being irreverent, detracting from the worship of God or being downright diabolical. For example Theodosius of Kiev, one of the co-founders of the Caves Monastery in the 11th century, called the skomorokhs "evils to be shunned by good Christians".[2] Their art was related and addressed to the common people and usually opposed the ruling groups, who considered them not just useless but even ideologically detrimental and dangerous by both the feudalists and the clergy.

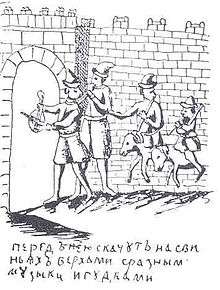

They were persecuted in the years of the Mongol yoke, when the church strenuously propagated ascetic living. Its art reached its peak in the 15th to the 17th centuries. Their repertoire included mock songs, dramatic and satirical sketches, called glumy (глумы), performed in masks and skomorokh dresses to the sounds of domra, balalaika, gudok, bagpipes or buben (a kind of tambourine). The appearance of Russian puppet theatre was directly associated with skomorokh performances.

Skomorokhs performed in the streets and city squares, engaging with the spectators to draw them into their play. Usually, the main character of the skomorokh performance was a fun-loving saucy muzhik (мужик) of comic simplicity. In the 16 and 17th centuries, skomorokhs would sometimes combine their efforts and perform in a vataga (ватага, big crowd) numbering 70 to 100 people. The skomorokhs were often persecuted by the Russian Orthodox Church and civilian authorities.

In 1648 and 1657, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich issued ukases banning skomorokh art as blasphemous, but actors would still occasionally perform during popular celebrations. In the 18th century, skomorokh art gradually died away; passing on some of its traditions to the balagans (балаган) and rayoks (раёк).

See also

References

- ↑ Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary entry for skomorokh

- ↑ Feodosii Pecherskii, Sochinenia, I. I. (Izmail Ivanovich) Sreznevksii, ed., in Ucheniia zapiski vtorogo otdelenie Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk, Vol. 2, no. 2, (St. Petersburg: Tipografii Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk, 1856), 195; See Russell Zguta, "Skomorokhi: The Russian Minstrel-Entertainers", Slavic Review 31 No. 2 (June 1972), 297–298; Idem, Russian Minstrels: A History of the Skomorokhi (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978).

External links

- Skomorokhi, the Troubadours of Old Rus