Sipuncula

| Sipuncula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| (unranked): | Sipuncula Rafinesque, 1814 |

| Classes, orders and families | |

| |

The Sipuncula or Sipunculida (common names sipunculid worms or peanut worms) is a group containing 144–320 species (estimates vary) of bilaterally symmetrical, unsegmented marine worms. Sipuncula signifies "little tube or siphon". Traditionally considered a phylum, they might be a subgroup of phylum Annelida based on recent molecular work.[1]

History

The first species of this phylum was described in 1827 by the French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville who named it Sipunculus vulgaris. A related species was later described as Golfingia macintoshii by E. Ray Lankester. The specimen was provided by a friend of his, Professor Mackintosh. The specimen was dissected by Lankester between rounds of golf at Saint Andrews golf club in Scotland from which the species derives its name. Golfingia is now the genus name and Sipuncula the name of the phylum to which these worms belong.

Habitat

Sipunculids are all marine. They are relatively common in shallow waters, either in burrows or in discarded shells as hermit crabs do. They are found especially below the surface on tidal flats.[2] Some bore into solid rocks to make a shelter for themselves. Although typically less than 10 cm long, some sipunculans may reach several times that length. The worms stay submerged in the sea bed between 10 and 18 hours a day and are sensitive to salinity, and thus not commonly found near estuaries.[2]

Anatomy

Sipunculans are worm-like animals ranging from 2 to 720 mm (0.1 to 28.3 in) in length, with most species being under 10 cm (4 in). The sipunculan body is divided into an unsegmented trunk and a narrower, retractable anterior section, called the "introvert". Sipunculans have a body wall somewhat similar to that of annelids (though unsegmented) in that it consists of a non-ciliated epidermis overlain by a cuticle, an outer layer of circular and an inner layer of longitudinal musculature. The body wall surrounds the coelom that is filled with fluid on which the body wall musculature acts as a hydrostatic skeleton to extend or contract the animal. When threatened, Sipunculids can retract their body into a shape resembling a peanut kernel—a practice that has given rise to the name "peanut worm". The introvert is retractable into the trunk via two pairs of retractor muscles that extend as narrow ribbons from the trunk wall to attachment points in the introvert. The introvert can be protruded from the trunk by contracting the muscles of the trunk wall, thus forcing the fluid in the body cavity forwards.[3]

The sipunculan mouth, located at the anterior end of the introvert, is surrounded by a mass of 18–24 ciliated tentacles in the Sipunculidea. In the Phascolosomatidea, the tentacles are arranged in an arc around the nuchal organ, also located at the tip of the introvert. The tentacles are used to gather organic detritus from the water or substrate, and probably also function as gills. In the family Themistidae the tentacles forms a crown, as the members of this group are specialized filter feeders, unlike the other sipunculans which are deposit feeders.[4] The tentacles at the tip of the introvert are hollow and are extended via hydrostatic pressure in a similar manner as the introvert, but have a separate system from that of the rest of the introvert; they are connected, via a system of ducts, to one or two contractile sacs next to the oesophagus.[3] Hooks are often present near the mouth on the introvert. These are proteinaceous, non-chitinous specializations of the epidermis, either arranged in rings or scattered.

Three genera (Aspidosiphon, Lithacrosiphon and Cloeosiphon) possess epidermal modifications, called the anal shield near the anteriorly located anus on the trunk just below the introvert of the animal.' In Aspidosiphon and Lithacrosiphon the anal shield is restricted to the dorsal side, causing the introvert to emerge at an angle, whereas it surrounds the anterior trunk in Cloeosiphon with the introvert emerging from its center. In Aspidosiphon the shield is a hardened, horny structure; in Lithacrosiphon it is a calcareous cone; in Cloeosiphon it is composed of separate plates. At the posterior end, a hardened caudal shield is sometimes present in Aspidosiphon.[5]

Digestive system

The digestive tract of sipunculans starts with the esophagus, located between the introvert retractor muscles. In the trunk the intestine runs posteriorly, forms a loop and turns anteriorly again. The downward and upward sections of the gut are coiled around each other, forming a double helix. At the termination of the gut coil, the rectum emerges and ends in the anus. A rectal caecum, present in most species, is a blind ending sac at the transition between intestine and rectum with unknown function. The anus is often not visible when the introvert is retracted into the trunk.[3]

Circulation

Sipunclans do not have a vascular blood system. Fluid transport and gas exchange are instead accomplished by the coelom, which contains the respiratory pigment haemerythrin, and the tentacular system. The coelomic fluid contains five types of coelomic cells: haemocytes, granulocytes, large multinuclear cells, ciliated urns and immature cells. The ciliated urn cells may also be attached to the peritoneum and assist in waste filtering from the interstitial fluid. Nitrogenous waste is excreted through a pair of metanephridia opening close to the anus, except in Phascolion and Onchnesoma, which have only a single nephridium.[3] A ciliated funnel, or nephrostome, opens into the coelomic cavity at the anterior end, close to the nephridiopore.

The tentacular system connects the tentacles at the tip of the introvert to a ring canal at their base, from which a contractile vessel that runs along the esophagus and ends blindly posteriorly. Some evidence points towards their involvement in ultrafiltration.[6]

Nervous system

The nervous system consists of a nerve ring (the cerebral ganglion) around the oesophagus, which functions as a brain, and a single ventral nerve cord that runs the length of the body.

In some species, there are simple light-sensitive ocelli associated with the brain. Two organs, likely functioning as a unit for chemoreception are located near the anterior margin of the cerebral ganglion: the non-ciliated cerebral organ, which possesses bipolar sensory cells, and the nuchal organ, located posterior to the cerebral organ.[3] Similar light-sensing tubes have been reported in the Fauvelopsid annelids.[7] In addition, all sipunculans have numerous sensory nerve endings on the body, especially at the forward end of the introvert.[3]

Reproduction

Both asexual and sexual reproduction can be found in sipunculans, although asexual reproduction is uncommon. Sipunculans reproduce asexually via transverse fission followed by regeneration of vital body components.

Most sipunculan species are dioecious. Their gametes are produced in the coelomic lining, where they are released into the coelom to mature. These gametes are then picked up by the metanephridia system and released into the aquatic environment, where fertilisation takes place.[3]

Life cycle

Although some species hatch directly into the adult form, many have a trochophore larva, which metamorphoses into the adult after anything from a day to a month, depending on species. In a few species, the trochophore does not develop directly into the adult, but into an intermediate pelagosphaera stage, that possesses a greatly enlarged metatroch (ciliated band).[8]

Metamorphosis occurs only in the presence of suitable sediment, and is triggered by the presence of adults.[9][10]

Taxonomy

The phylogenetic placement of this phylum in the past has proved troublesome. Originally classified as annelids, despite the complete lack of segmentation, bristles and other annelid characters, the phylum Sipuncula was later allied with the Mollusca, mostly on the basis of developmental and larval characters. Currently these two phyla have been included in a larger group, the Lophotrochozoa, that also includes the annelids, the ribbon worms and several other phyla. Phylogenetic analyses based on 79 ribosomal proteins indicated a position of Sipuncula within Annelida.[11] Subsequent analysis of the mitochondrion's DNA has confirmed their close relationship to the Myzostomida and Annelida (including echiurans and pogonophorans).[12] It has also been shown that a rudimentary neural segmentation similar to that of annelids occurs in the early larval stage, even if these traits are absent in the adults.[13]

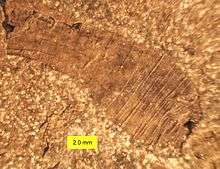

Fossil record

Fossils of sipunculans are extremely rare, and are only known from a few genera:

- Archaeogolfingia and Cambrosipunculus appear in the Cambrian Chengjiang biota in China. These fossils appear to belong to the crown group,[14][15] and demonstrate that sipunculans have changed little (morphologically) since the early Cambrian, about 520 million years ago.[14]

- An unnamed worm from the Burgess Shale in Alberta, Canada.[16]

- The Silurian/Carboniferous Lecthaylus.[17]

- Others[14]

Some scientists once hypothesized a close relationship between sipunculans and the extinct hyoliths, operculate shells from the Palaeozoic with which they share a helical gut; but this hypothesis has since been discounted.[18]

As food

Sipunculid worm jelly (土笋凍) is a delicacy in southeast Fujian province of China, originally from Anhai Town of Quanzhou, the starting point of the recent Chinese initiative, the "maritime Silk Road" .

A sipunculid worm dish is also a delicacy in the islands of the Visayas region, Philippines. This is usually prepared by cleaning the muscle and soaking it in vinegar and spices in a style similar to ceviche. It is a common meal for fisherfolk and is a sought-after but not so common appetizer in city restaurants. This style of food preparation is locally called kilawin or kinilaw, and is also done for fish, conch, and vegetables.

The worms, especially in dried form, are considered a delicacy in Vietnam as well, where they are caught on the coasts of Minh Chao island, in Van Don District.[19] The high market price of the worms have made them a significant source of income for the local population of fishermen families.[2]

A plate of Sipunculid worm jelly.

A plate of Sipunculid worm jelly. This sipunculid worm dish is made by adding vinegar and local spices. Taken in Cebu, Philippines.

This sipunculid worm dish is made by adding vinegar and local spices. Taken in Cebu, Philippines.

References

- ↑ Struck, T. H.; Paul, C.; Hill, N.; Hartmann, S.; Hösel, C.; Kube, M.; Lieb, B.; Meyer, A.; Tiedemann, R.; Purschke, G. N.; Bleidorn, C. (3 March 2011). "Phylogenomic analyses unravel annelid evolution". Nature. 471 (7336): 95–98. doi:10.1038/nature09864. PMID 21368831.

- 1 2 3 Nguyen, Thi Thu Ha, et al. "The distribution of peanut-worm (Sipunculus nudus) in relation with geo-environmental characteristics." (2007).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 863–870. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ↑ The Sipuncula: Their Systematics, Biology, and Evolution

- ↑ Schulze, A.; et al. (March 2005). "Reconstructing the phylogeny of the Sipuncula". Hydrobiologia. 535/536: 277–296. doi:10.1007/s10750-004-4404-3.

- ↑ Pilger, J. F. & Rice, M. E. (1987). "Ultrastructural evidence for the contractile vessel of sipunculans as a possible ultrafiltration site". American Zoology. 27: 810a.

- ↑ Purschke, Günter (2011). "Sipunculid‐like ocellar tubes in a polychaete, Fauveliopsis cf. adriatica (Annelida, Fauveliopsidae): implications for eye evolution". Invertebrate Biology. 130 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2011.00226.x.

- ↑ Rice, M. E. (1976). Larval development and metamorphosis in Sipuncula. American Zoologist, 16, 563–571.

- ↑ Pechenik, J. A., & Rice, M. E. (1990). Influence of delayed metamorphosis on postsettlement survival and growth in the sipunculan ~Apionsoma misakianum~. Invertebrate Biology, 120(1), 50–57. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7410.2001.tb00025.x

- ↑ Rice, M. E. (1986). Factors influencing larval metamorphosis in ~Golfingia misakiana~ (Sipuncula). Bulletin of Marine Science, 39(2), 362–375.

- ↑ Hausdorf, B.; et al. (2007). "Spiralian Phylogenomics Supports the Resurrection of Bryozoa Comprising Ectoprocta and Entoprocta". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (12): 2723–2729. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm214. PMID 17921486.

- ↑ Shen, X.; Ma, X.; Ren, J.; Zhao, F. (2009). "A close phylogenetic relationship between Sipuncula and Annelida evidenced from the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Phascolosoma esculenta". BMC Genomics. 10: 136. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-136. PMC 2667193. PMID 19327168.

- ↑ Wanninger, Andreas; Kristof, Alen; Brinkmann, Nora (Jan–Feb 2009). "Sipunculans and segmentation". Communicative and Integrative Biology. 2 (1): 56–59. doi:10.4161/cib.2.1.7505. PMC 2649304. PMID 19513266.

- 1 2 3 Huang, D. -Y.; Chen, J. -Y.; Vannier, J.; Saiz Salinas, J. I. (22 August 2004). "Early Cambrian sipunculan worms from southwest China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1549): 1671–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2774. PMC 1691784. PMID 15306286.

- ↑ Eibye-Jacobsen, D.; Vinther, J. (February 2012). "Reconstructing the ancestral annelid". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 50: 85–87. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2011.00651.x.

- ↑ Caron, J. -B.; Gaines, R. R.; Mangano, M. G.; Streng, M.; Daley, A. C. (2010). "A new Burgess Shale-type assemblage from the "thin" Stephen Formation of the southern Canadian Rockies". Geology. 38 (9): 811–814. doi:10.1130/G31080.1.

- ↑ Muir, L. A.; Botting, J. P. (2007). "A Lower Carboniferous sipunculan from the Granton Shrimp Bed, Edinburgh". Scottish Journal of Geology. 43: 51–56. doi:10.1144/sjg43010051.

- ↑ Moysiuk,Joseph; Smith, Martin R.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2017). "Hyoliths are Palaeozoic lophophorates". Nature. 541: 394–397. doi:10.1038/nature20804.

- ↑ "Women earn a living digging for peanut worms in northern Vietnam - Tuoi Tre News".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sipuncula. |