Dakota people

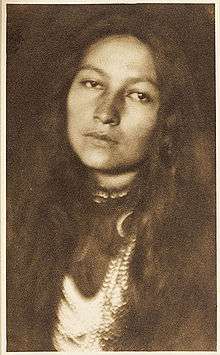

Charles Alex Eastman (1858–1939), physician, author, and co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,460 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Dakota,[1] English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), traditional tribal religion, Native American Church, Wocekiye | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lakota, Assiniboine, Stoney (Nakota), and other Sioux |

The Dakota people are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux /ˈsuː/ people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Western Dakota.

The Eastern Dakota are the Santee (Isáŋyathi or Isáŋ-athi; "knife" + "encampment", ″dwells at the place of knife flint″), who reside in the eastern Dakotas, central Minnesota and northern Iowa. They have federally recognized tribes established in several places.

The Western Dakota are the Yankton, and the Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), who reside in the Upper Missouri River area. The Yankton-Yanktonai are collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena (″Those Who Speak Like Men″). They also have distinct federally recognized tribes.

In the past the Western Dakota have been erroneously classified as Nakota, a branch of the Sioux who moved further west. The latter are now located in Montana and across the border in Canada, where they are known as Stoney.[2]

Name

The word Dakota means "ally" in the Dakota language, and their autonyms include Ikčé Wičhášta ("Indian people") and Dakhóta Oyáte ("Dakota people").[3]

Ethnic groups

The Eastern and Western Dakota are two of the three groupings belonging to the Sioux nation (also called Dakota in a broad sense), the third being the Lakota (Thítȟuŋwaŋ or Teton). The three groupings speak dialects that are still relatively mutually intelligible. This is referred to as a common language, Dakota-Lakota, or Sioux.[4]

The other two languages of the Dakotan dialect continuum, Assiniboine and Stoney (spoken by the Nakota or Nakoda peoples), have grown widely or completely unintelligible to Dakota and Lakota speakers.[5]

The Dakota include the following bands:

- Santee division (Eastern Dakota) (Isáŋyathi, meaning "knife camp"[3])[5]

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])[5]

- notable persons: Taoyateduta

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, translating to "swamp/lake/fish scale village"[3])

- Wahpekute (Waȟpékhute, "Leaf Archers")[5]

- notable persons: Inkpaduta

- Wahpeton (Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, "Leaf Village")[5]

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])[5]

- Yankton-Yanktonai division (Western Dakota) (Wičhíyena)

In the 21st century, the majority of the Santee live on reservations, reserves, and communities in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Canada. Some have moved to cities for more work opportunities. In the north woods of Minnesota, some Santee continue to live in historic communities at the Ottertail Lake and Inspiration Peak areas. Their ancestors were never sent to reservations, as they were protected by settlers whom they had befriended.

After the Dakota War of 1862, the federal government expelled the Santee from Minnesota. Many were sent to Crow Creek Indian Reservation. In 1864 some from the Crow Creek Reservation were sent to St. Louis and then by boat up the Missouri River, ultimately to the Santee Sioux Reservation.

The Bdewákaŋthuŋwaŋ (Mdewakanton) live predominantly at the Prairie Island and Shakopee reservations in Minnesota.

Most of the Yankton live on the Yankton Indian Reservation in southeastern South Dakota. Some Yankton live on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation and Crow Creek Reservation, which is also occupied by the Lower Yanktonai.

The Upper Yanktonai live in the northern part of Standing Rock Reservation, on the Spirit Lake Reservation in central North Dakota. Others live in the eastern half of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana. In addition, they reside at several Canadian reserves, including Birdtail, Oak Lake, and Whitecap (formerly Moose Woods).

History

Pre-history

It is difficult to determine exactly where the Dakota people came from before the recorded era. The most similar people to them linguistically were Great Lakes–region speakers of Chiwere, a linguistically conservative (i.e., similar to ancient proto-Siouan) Siouan language. However, the Dakota language, Lakotaiapi, is also very closely related to that of the Dhegihan and Hokan Siouan peoples — both of whom have oral histories explaining that they came west from present-day Ohio in migrations ending around the 13th century.

A single line of older history seems to have survived from the Dakotas — that they had come to live with the Winnebago, but the Winnebago soon became angry and ordered them to leave. Combining this with the histories of the Dhegihans, it is possible to surmise that the ancestors of the Dakota people may have also been refugees from further east who started taking refuge with other Siouan allies — possibly even predating the move of the Dhegihan Sioux peoples. The Winnebago may have been forced to send the Dakota off to find a new homeland because of overcrowding or because the Dhegihans' arrival on the Plains disrupted commerce and trading along the Mississippi River. Either explanation, however, can only be an educated guess.[7]

First contacts with Europeans

The Dakota Oyate are said to have lived in Minnesota prior to the 18th century.[3][8] Most of their early history was recorded (haphazardly) by a white man named James Walker close to the end of the 19th century, as he offered aid among the Lakota/Dakota people. He recorded much of what he knew in three books: Lakota Myth, Lakota Belief and Ritual, and Lakota Society. According to Walker, the group was originally one people with one chief, which grew and developed four sub-factions over time, each with their own equal chiefs. In these two groups there also evolved two distinct dialects of the original language, Nakota and Dakota. Their capitol was situated at a place known as Ble Wakan (recorded as "Boo-reh wah-kaw"), which is currently identified as Lake Mille Lac (known in Dakota as Bde Wakan).[9]

Late in the 17th century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants.[10] The French were trying to gain an advantage in the struggle for the North American fur trade against the English, who had recently established the Hudson's Bay Company. While many people believe that the name "Sioux" derives from an Ojibwe racial slur directed towards them, it is far more likely that the title Sioux came from the early French explorers. They originally named the Mississippi River the direct French translation for the Ojibwe name, "Great River," which was Sioux Tango, at least, before the other Ojibwe name for the river, Michi Ziibi, managed to stick. The Dakota were known to be directly related to the source of the Mississippi.

Though details are scarce, sometime near the end of the 17th century, some sort of war occurred between Siouan and Algonquian peoples between Lake Superior and the Mississippi River. The Dakota were driven away from the river and off onto the Great Plains, where they were forced to wage a long military campaign to displace several lesser-known tribes in the region of present-day North and South Dakota. Also affected in this original war were the Fox/Menominee people (who moved from the western shore of Lake Superior to the region of the Michigan–Wisconsin border), the Winnebago, and the Illinois Confederacy (who broke up and were moved across the Mississippi River by the French). Displaced local Algonquian, Caddoan, Chiwere and Dhegihan peoples already on the Plains fought back fiercely for decades before the situation settled. Many tribes were completely, or nearly, wiped out during this time.

After this, there was apparently a split among the Dakota people and two new groups — the Hohe and the Lakota — split off from them. While these groups originally operated as their own separate nations, it appears that they eventually merged back together to form the Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Fire Council, by the early to mid-19th century.[11] The Hohe returned to Minnesota, where they earned the nickname Asinii Bwaan, or Stone Sioux, from the Ojibwe (from their use of hot stones to boil water).[12][13] To this day, the Hohe are primarily known as the Assiniboine. Many of those who left were part of the Nakota and, which caused the Nakota to lose their military superiority to the Santee Dakota. It was roughly around this point that all these peoples began to generally refer to themselves as the Dakota People.[11] After their far later defeat by the United States, the Nakota would dissolve and merge with the Lakota and Dakota, and the Dakota would shrink. Only the smallest of the four groups, the Lakota, managed to thrive and grow in the enclosed space allowed them by the U.S. government. Despite this, all four dialects of the Lakotaiapi language have managed to survive into the modern day.

According to Lakota Society, the names of the seven tribes seem to have been divided as such:

- Nakota: Mdewakan and Wahepetonwan (Leaf Shooter)

- Dakota: Isáŋ-athi (Santee) and Sissetonwan

- Hohe: Yankton (Crooked Ones) and Yanktonai (Followed the Crooked Ones)

- Lakota: Titonwan

Confusion stems from the reorganization of the tribes afterward, and the fact that many of them went my multiple nicknames — even to the point that Walker misidentified the three names of the Dakota people as the Teton, Sicangu and Brule. Also, the Wahepeton are currently associated with the Dakota, as are the Mdewakan. Moreover, many people associated with this confederation fled to Canada when they lost hope of victory over the U.S., and peoples were thus split across borders.

Dakota War of 1862

By 1862, shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and one trader, Andrew Myrick, went so far as to say, "If they're hungry, let them eat grass."[14] On August 17, 1862, the Dakota War began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family. They inspired further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. The Santee attacked the trading post. Later settlers found Myrick among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass.[15]

On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in courts-martial, 303 Santee Dakota were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of American settlers. They were sentenced to be hanged. No attorneys or witness were allowed as a defense for the accused, and many were convicted in less than five minutes of court time with the judge.[16] President Abraham Lincoln commuted the death sentence of 284 of the warriors, while signing off on the execution of 38 Santee men by hanging on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota. Forty-three-year-old Alexander Wilkin commanded the executions, which together amounted to the largest single mass execution in U.S. history.[17]

Afterwards, the US suspended treaty annuities to the Dakota for four years and awarded the money to the white victims and their families. The men remanded by order of President Lincoln were sent to a prison in Iowa, where more than half died.[16]

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota to Canada, or settled in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri.[16] A few joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military.[16]

Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the 21st century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some ended up in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Tribe today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri.

Those who fled to Canada now have descendants residing on nine small Dakota Reserves, five of which are located in Manitoba (Sioux Valley, Dakota Plains, Dakota Tipi, Birdtail Creek, and Oak Lake [Pipestone]) and the remaining four (Standing Buffalo, Moose Woods [White Cap], Round Plain [Wahpeton], and Wood Mountain) in Saskatchewan.

Reserves and First Nations

In Minnesota, the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851 left the Dakota with a reservation 20 miles (32 km) wide on each side of the Minnesota River.

In Canada, the Canadian government recognizes the tribal community as First Nations. The land holdings of these First Nations are called Indian Reserves.

Modern reservations, reserves, and communities of the Sioux

| Reserve/Reservation[18] | Community | Bands residing | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fort Peck Indian Reservation | Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes | Hunkpapa, Upper Yanktonai (Pabaksa), Sisseton, Wahpeton, and the Hudesabina (Red Bottom), Wadopabina (Canoe Paddler), Wadopahnatonwan (Canoe Paddlerrs Who Live on the Prairie), Sahiyaiyeskabi (Plains Cree-Speakers), Inyantonwanbina (Stone People) and Fat Horse Band of the Assiniboine | Montana, United States |

| Spirit Lake Reservation

(Formerly Devil's Lake Reservation) |

Spirit Lake Tribe

(Mni Wakan Oyate) |

Wahpeton, Sisseton, Upper Yanktonai | North Dakota, USA |

| Standing Rock Indian Reservation | Standing Rock Sioux Tribe | Upper Yanktonai, Hunkpapa | North Dakota, South Dakota, USA |

| Lake Traverse Indian Reservation | Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate | Sisseton, Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Flandreau Indian Reservation | Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Crow Creek Indian Reservation | Crow Creek Sioux Tribe | Lower Yanktonai | South Dakota, USA |

| Yankton Sioux Indian Reservation | Yankton Sioux Tribe | Yankton | South Dakota, USA |

| Upper Sioux Indian Reservation | Upper Sioux Community

(Pejuhutazizi Oyate) |

Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton | Minnesota, USA |

| Lower Sioux Indian Reservation | Lower Sioux Indian Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Shakopee-Mdewakanton Indian Reservation

(Formerly Prior Lake Indian Reservation) |

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Prairie Island Indian Community | Prairie Island Indian Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Santee Indian Reservation | Santee Sioux Nation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Nebraska, USA |

| Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Sioux Valley First Nation | Sisseton, Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute | Manitoba, Canada |

| Dakota Plains Indian Reserve 6A | Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Dakota Tipi 1 Reserve | Dakota Tipi First Nation | Wahpeton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Birdtail Creek 57 Reserve, Birdtail Hay Lands 57A Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Birdtail Sioux First Nation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation, Oak Lake 59A Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation | Wahpekute, Wahpeton, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Standing Buffalo 78 Reserve | Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation | Sisseton, Wahpeton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Whitecap 94 Reserve | Whitecap Dakota First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Dakota Plains Wahpeton Reserve | Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation | Wahpeton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Wood Mountain 160 Reserve, Treaty Four Reserve Grounds Indian Reserve No. 77* | Wood Mountain | Hunkpapa | Saskatchewan, Canada |

(* Reserves shared with other First Nations)

Daily life

Hints from legends claim that they were originally more settled and did farm corn, earth beans and pumpkins in their original homeland. They also harvested local plants, such as Tipsila (a wild North American turnip), American Wild Rice, Various types of nuts and berries and some form of wild potato and hunted animals like the Buffalo, whom the native people always held in high regard. As per the rumors, they always tried to use every part of the Buffalo and never be wasteful. Their homes would have still been tipis, or something alike a tipi that was more permanent. Technically, these homes are called Ti, or Oti. Tipi would be plural.[9]

After being driven onto the plains, life was harder. The people were unable to farm the land and took to yearly migration cycles, following the Buffalo closely. Despite having separate homelands, the migrations would often take certain groups into the territories of one another. This made acquiring things like corn and Tobacco extremely difficult. Tobacco, usually used as incense for holy ceremonies and habitually smoked, had to be reserved for very special occasions and was often replaced by the abundant sweet grass found on the Plains. Many of their ceremonies, such as one holiday that took place during the first planting season, no longer held any relevance and the culture diverged from its original form greatly. Hope did come, however, with the horse. The Lakota managed to win a major conflict with the Cheyenne and got horses in the deal. This revelation made many aspects of life far easier and all the Dakota people quickly evolved into a horse-riding culture. Their word for horse is Sunkawakan, or Holy Dog.

Each of the seven tribes were said to have been divided into smaller and smaller subgroups that eventually came down to individual camps and there was a hierarchy of chiefs going back up to the main seven High Chiefs. Similar to the idea of Moieties from eastern native peoples, a child was considered a relative of both his father and mother's camps and could marry no one from either. Since the migrations generally brought them into closer proximity to the same camps over and over again, this quickly caused serious problems for the legality of marriage. Some of the peoples chose to forego the law, but most were disturbed by the possibility, likening it to incest in their minds, and refused. It's probably because of this, as well as constant warfare, that the acquisition of women as conquest and slave property became more and more common among the Dakota Oyate. The women did have their own rights, but it seems like most of these were in place more to preserve the honor of their men as warriors and not to really protect them. Unless they had close relatives who they could reach, or were able to maneuver themselves to get help from another man, these women were basically trapped. Polygamy was also allowed, as it was among most native peoples in one form or another.

The ordering of camps was fairly simple. The tents were always organized into circles with the entrance facing the rising sun and the most important home centered directly at the west end. The families within these tents also slept in a similar manner, with the head of household directly across from the door, the eldest son to one side, the second eldest to the right, and little general order beyond that. The ordering of the tents would get more and more complicated, depending on what all groups happened to be camping together.

The chiefs could be male or female (although female chiefs were rare) and were counseled by an ever-changing group of elders, depending on the situation. Apparently, these councilors were almost always male. A type of police force known as the Akicita were organized to keep the peace and other military and religious societies and organizations provided different services to the community in both war and peace-times. The Chief elected the lead Akicita, and this person nominated his officers as he saw fit, as did the other groups. Seemingly, it was also considered a crime to turn down an offer to take on a title, with the exception of chief, once publicly nominated. Men and women both were also allowed to be nominated to any position. Punishments for crime were said to have been beatings, destruction of property, posting bail and, in worst-case scenarios, death. For whatever reason, posting bail was generally looked down upon as the cowards' way out.[11]

Language

The Dakota language is a Mississippi Valley Siouan language, belonging to the greater Siouan-Catawban language family. It is closely related to and mutually intelligible with the Lakota language, and both are also more distantly related to the Stoney and Assiniboine languages. Dakota is written in the Latin script and has a dictionary and grammar.[1]

- Eastern Dakota (also known as Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

- Western Dakota (or Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta)

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Upper Yanktonai (Wičhíyena)

Modern geographic divisions

The Dakota maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North America: in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Montana in the United States; and in Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Dakota identified them in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. After the introduction of the horse in the early 18th century, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land—from present day Central Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Powder River country.[19]

Santee (Isáŋyathi or Eastern Dakota)

The Santee migrated north and westward from the Southeast United States, first into Ohio, then to Minnesota. Some came up from the Santee River and Lake Marion, area of South Carolina. The Santee River was named after them, and some of their ancestors' ancient earthwork mounds have survived along the portion of the dammed-up river that forms Lake Marion. In the past, they were a Woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and farming.

Migrations of Ojibwe people from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Dakota further into Minnesota and west and southward. The US gave the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi River and up to its headwaters.[20]

Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yankton-Yanktonai or Western Dakota)

The Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, also known by the anglicized spelling Yankton (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ: "End village") and Yanktonai (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna: "Little end village") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the Lower Yanktonai (Húŋkpathina).[20]

They were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, they were recorded as living in the Mankato (Maka To – Earth Blue/Blue Earth) region of southwestern Minnesota along the Blue Earth River.[21]

Notable Dakota people

Historical

- Inkpaduta (Scarlet Point/Red End), Wahpekute Dakota war chief

- Ištáȟba (Sleepy Eye), Sisseton Dakota chief

- Ohíyes'a (Charles Eastman), Dakota author, physician and reformer

- Tamaha (One Eye/Standing Moose), Mdewekanton Dakota chief

- Thaóyate Dúta (Little Crow/His Red Nation), Mdewakanton Dakota chief and warrior

- Wanata, War Eagle, Húŋkpathina

- Waŋbdí Tháŋka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton Dakota chief

- Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, 1876–1938), Yankton author, educator, musician and political activist

Contemporary

- Ella Cara Deloria (1889 – 1971), author, ethnographer, linguist

- Vine Deloria Jr. (1933–2005), Standing Rock author, activist, historian and theologian

- Floyd Red Crow Westerman/Kanghi Duta (1936–2007), Sisseton Wahpeton actor

- John Trudell (1946–2015), Santee activist, American Indian Movement leader

Contemporary Sioux people are also listed under the tribes to which they belong:

By individual tribe

- Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe of the Crow Creek Reservation

- Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe of the Lower Brule Reservation

- Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community

- Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota

- Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 "Dakota." Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ For a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming the Yankton and the Yanktonai as "Nakota", see the article Nakota

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barry M. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000; pg. 316

- ↑ Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L., "The Siouan languages"; in DeMallie, R.J. (ed) (2001). Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114) [W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.)]. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution: pp. 97 ff; ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ullrich, Jan (2008). New Lakota Dictionary (Incorporating the Dakota Dialects of Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton). Lakota Language Consortium. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-9761082-9-1.

- ↑ not to be confused with the Oglala thiyóšpaye bearing the same name, "Húŋkpathila"

- ↑ Louis F. Burns, "Osage" Archived January 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, retrieved 2 March 2009

- ↑ Hyde, George E. (1984). Red Cloud's Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8061-1520-3.

- 1 2 DeMallie, Raymond J. & Jahner, Elaine A. "Lakota Myth (Second Edition)" 2006.

- ↑ van Houten, Gerry (1991). Corporate Canada An Historical Outline. Toronto: Progress Books. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-919396-54-2.

- 1 2 3 DeMallie, Raymond J. & Jahner, Elaine A. "Lakota Society" 1992.

- ↑ Nichols, John & Nyholm, Earl "Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe" 1994.

- ↑ Bryce, George (1893). The Assiniboine River and its Forts. Trans. Roy. Soc. Canada. pp. Section II, p. 69.

- ↑ Dillon, Richard (1993). North American Indian Wars. City: Booksales. p. 126. ISBN 1-55521-951-9.

- ↑ Steil, Mark; Tim Post (2002-09-26). "Let them eat grass". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- 1 2 3 4 War for the Plains. Time-Life Books. 1994. ISBN 0-8094-9445-0.

- ↑ Steil, Mark; Tim Post (2002-09-26). "Execution and expulsion". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael (2000). The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Osprey Publishing Oxford. ISBN 1-85532-878-X.

- ↑ Mails, Thomas E. (1973). Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-13-217216-X.

- 1 2 Riggs, Stephen R. (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Washington Government Printing Office, Ross & Haines, Inc. ISBN 0-87018-052-5.

- ↑ OneRoad, Amos E.; Alanson Skinner (2003). Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-453-X.

Further reading

- Catherine J. Denial, Making Marriage: Husbands, Wives, and the American State in Dakota and Ojibwe Country. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dakota (Sioux). |