Single skating

| |

| Highest governing body | International Skating Union |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Team members | Individuals |

| Equipment | Figure skates |

| Presence | |

| Olympic |

Part of the Summer Olympics in 1908 and 1920; Part of the first Winter Olympics in 1924 to today |

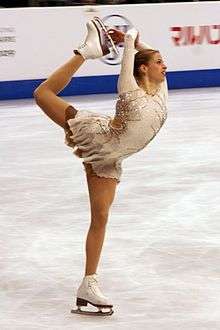

Single skating is a discipline of figure skating in which male and female skaters compete individually. Men's singles and ladies' singles[1] are both Olympic disciplines and are both governed by the International Skating Union, along with the other Olympic figure skating events, pair skating and ice dancing. Single skaters perform jumps, spins, step sequences, spirals, and other moves in the field as part of their competitive programs.

Competition segments

Short program

.jpg)

The short program is the first segment of single skating, pair skating, and synchronized skating in international competitions, including all ISU championships, the Olympic Winter Games, the Winter Youth Games, qualifying competitions for the Olympic Winter Games, and ISU Grand Prix events for both junior and senior-level skaters (including the finals).[2]:p. 9[3]:p. 7 The short program must be skated before the free skate, the second component in competitions.[2]:p. 10[3]:p. 7 The short program lasts, for both senior and junior singles and pairs, 2 minutes and 40 seconds.[2]:p. 78 Vocal music with lyrics has been allowed in single skating and in all disciplines since the 2014-2015 season.[4] Yuzuru Hanyu from Japan holds the highest single men's short program score of 112.72 points, which he earned at the 2017 CS Autumn Classic International in Montreal, Quebec.[5] Russian skater Alina Zagitova holds the highest single women's short program score of 82.92, which she earned at the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang, South Korea.[6][4]

The short program for senior single skaters consists of seven required elements. The sequence of the elements is optional. Skaters can choose their own music, but their programs must be skated in harmony with it. Men single senior skaters must have the following elements in their short program: a double or triple axel; one triple or quadruple jump; a jump combination consisting of either a double jump and a triple jump, two triple jumps, a quadruple jump and a double jump, or a triple jump; one flying spin; a camel spin or sit spin with just one change of foot; a spin combination with just one change of foot; and a step sequence using the entire ice surface.[2]:p. 103 Women single senior skaters must perform seven elements in their short program: a double or triple axel; one triple jump; a jump combination consisting of either a double jump and a triple jump, or two triple jumps; one flying spin; either a layback/sideways leaning spin or a sit or camel spin without a change of foot; a spin combination with just one change of foot; and a step sequence using the entire ice surface.[2]:p. 104[7] Junior single skaters also have seven required elements.[2]:pp. 104-105

Free skating

Free skating, also called the free skate or long program, is the second segment in single skating, pair skating, and synchronized skating in international competitions, including all ISU championships, the Olympic Winter Games, the Winter Youth Games, qualifying competitions for the Olympic Winter Games, and ISU Grand Prix events for both junior and senior-level skaters (including the finals).[2]:p. 9 Its duration, across all disciplines, is 4 minutes for senior skaters and teams, and 3 1/2 minutes for junior skaters.[2]:p. 79 Russian skater Mikhail Kolyada holds the highest single men's free skating program score of 177.55, which he earned at the 2018 CS Ondrej Nepela Trophy.[8] Alina Zagitova, also from Russia, holds the highest single women's free skating score of 158.50, which she earned at the 2018 CS Nebelhorn Trophy.[9]

According to the ISU, free skating "consists of a well balanced program of Free Skating elements, such as jumps, spins, steps and other linking movements".[2]:p. 108 A well-balanced free skate for both senior men and women single skaters must consist of the following: up to seven jump elements, one of which has to be an axel jump; up to three spins, one of which has to be a spin combination (one a spin with just one position, and one flying spin with a flying entrance); only one step sequence; and only one choreographic sequence.[2]:pp. 108-109 Junior men and women single skaters have the same requirements, except that they do not have to perform a choreographic sequence.[2]:p. 109

Compulsory figures

Compulsory figures, also called school figures, are the "circular patterns which skaters trace on the ice to demonstrate skill in placing clean turns evenly on round circles".[10] Until 1947, for approximately the first half of the existence of figure skating as a sport, compulsory figures made up for 60 percent of the total score at most competitions around the world.[11] After World War II, the numbers of figures skaters had to perform during competitions decreased, and after 1968, they began to be progressively devalued, until the ISU voted to remove them from all international competitions in 1990.[11][12]:p. 82 Despite the apparent demise of compulsory figures from the sport of figure skating, coaches continued to teach figures and skaters continued to practice them because figures gave skaters an advantage in developing alignment, core strength, body control, and discipline.[13] The World Figure Sport Society has conducted festivals and competitions of compulsory figures, endorsed by the Ice Skating Institute, since 2015.[14]

Judging

Figure skaters competing in an ISU-sanctioned event are judged under the ISU Judging System.[15][16][17][18]

Music, clothing, and skates

Competitors often choose music in consultation with their coach and choreographer.[19] For long programs, skaters generally search for music with different moods and tempos.[19] In competitive programs, vocal music was previously allowed only if it contained no lyrics or words, but in June 2012, the International Skating Union voted to allow music with words in competitive programs beginning in the 2014–15 season.

Figure skates for single skaters possess a larger set of jagged teeth called toe picks on the front of the blade than skates used by ice dancers. The toe picks are used primarily in jumping and footwork. The inside edge of the blade is on the side closest to the skater; the outside edge of the blade is on the side farthest from the skater. In figure skating it is always desirable to skate on only one edge of the blade, never on both at the same time (which is referred to as a flat). The apparently effortless power and glide across the ice exhibited by elite figure skaters fundamentally derives from efficient use of the edges to generate speed.

Skaters and family members may design their own costumes or turn to professional designers.[20][21][22]

References

- ↑ Note: Women are referred to as ladies in International Skating Union regulations.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2018". International Skating Union. June 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Synchronized Skating 2016". International Skating Union. June 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- 1 2 Root, Tik (8 February 2018). "How to watch figure skating at the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "Personal Best: Men". International Skating Union. 24 March 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "Personal Best: Ladies". International Skating Union. 24 March 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "Figure Skating 101: Get to Know the Rules and Scoring". NBC Washington.com. NBC Universal Media. 18 February 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Personal Best: Men". International Skating Union. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Personal Best: Ladies". International Skating Union. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Special Regulations For Figures" (PDF). U.S. Figure Skating Association. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- 1 2 Loosemore, Sandra (16 December 1998). "'Figures' don't add up in competition anymore". CBS SportsLine. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- ↑ Sausa, Christie (1 September 2015). "Figures revival". Lake Placid News. Lake Placid, N.Y. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "World Figure Championship & Figure Festival coming to Lake Placid, NY" (Press release). Lake Placid, N.Y.: World Figure Sport Society. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "Communication No. 1861: Single & Pair Skating Scale of Values, Levels of Difficulty and Guidelines for marking Grade of Execution" (PDF). International Skating Union. 28 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "Special Regulations & Technical Rules: Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2012" (PDF). International Skating Union. June 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ "S&P Deductions - Deductions: Who is responsible?" (PDF). International Skating Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010.

- ↑ "ISU: Single and Pair Skating: Technical Panel Handbooks, Communications, Questions and Answers". Archived from the original on 24 July 2013.

- 1 2 Brannen, Sarah S. (23 April 2012). "Beyond 'Carmen': Finding the right piece of music". Ice Network. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Brannen, Sarah S. (20 August 2012). "Fashion forward: Designers, skaters on costumes". Icenetwork.

- ↑ Golinsky, Reut (14 September 2012). "Costumes on Ice, Part II: Ladies". Absolute Skating.

- ↑ Golinsky, Reut (4 October 2012). "Costumes on Ice, Part III: Men". Absolute Skating.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Single skating. |