Siege of Turin

| Siege of Turin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

The Prussians break the French line at Stura, outside Turin 7 September 1706 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Garrison; 14,500 plus 8,000 militia Relief force; 30,000 | 40,000–48,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,000–11,000 dead or wounded |

16,000–18,000 dead or wounded 6,000 captured[1] | ||||||

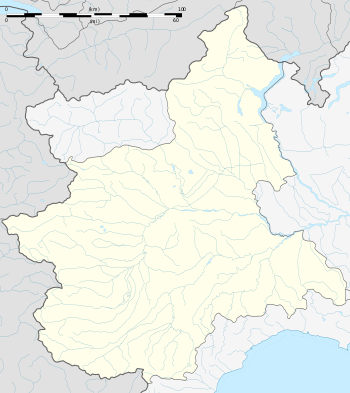

The Siege of Turin lasted from June to September 1706 when a French-led force besieged the Savoyard capital of Turin during the War of the Spanish Succession. The siege was broken when a combined Savoyard/Imperial army relieved the city in September; this was a major turning point for the war in Italy.

Background

By October 1705, France and its allies controlled most of Northern Italy, as well as the Savoyard territories of Villefranche and the County of Savoy, now in modern-day France. Victor Amadeus retained only his capital Turin but Vendôme decided it was too late in the year for a full-scale assault, which was delayed until 1706.[2]

On 19 April, Vendôme defeated Imperial forces at Calcinato in Lombardy, driving them into the Trentino valley which he hoped would prevent them interfering at Turin. The Austrian commander Prince Eugene returned from Vienna and quickly restored order, taking his remaining forces around Lake Garda and into the Province of Verona.[lower-alpha 1] This left 30,000 Imperial troops around Verona facing 40,000 French spread between the Mincio and Adige rivers.[3]

Marshall Louis de La Feuillade and 48,000 men arrived before Turin on 12 May, although it was not until 19 June that they completed their blockade of the city.[4] However, the strategic position changed with the disastrous French defeat at Ramillies on 23 May; Vendôme returned to France and on 8 July Philippe II, Duke of Orléans assumed command in Italy, with Marshal Ferdinand de Marsin as his advisor.[5]

The siege

As was customary, Turin's defences were divided between the outer City which held the residential and commercial areas with the Citadel at its core. La Feuillade and Vendôme planned to dig trenches around the City at a distance of 300-400 metres, then blast the Citadel into submission but the French engineer Vauban argued it was too strong for this to work.[lower-alpha 2] The Citadel had been significantly improved, based on advice provided by Vauban himself and much of it was underground; he recommended taking the City first, which would allow the artillery to target the base of the Citadel's walls, rather than the higher parts.[6] The French commanders ignored this and Vauban allegedly offered to have his throat cut if Turin were to be captured using this approach.[7]

Leaving Philipp von Daun in command of the garrison, Victor Amadeus left the city on 17 June with 6,000 cavalry, seeking to disrupt French supply lines and buy time for Prince Eugene's relief force to reach him. La Feuillade spent most of the next month chasing him around Southern Piedmont but by the end of July, it was clear the siege was moving too slowly. As Vauban predicted, the bombardment inflicted considerable damage but the Citadel walls remained intact and on 15 August Prince Eugene began his advance on Turin. Orléans' covering force failed to stop him and joined La Feuillade; their combined forces assaulted the Citadel three times between 27 August and 3 September but were all repulsed with heavy loss.[lower-alpha 3]

On 29 August Prince Eugene reached Carmagnola, where he was joined by Victor Amadeus. Often overlooked, this was perhaps the most remarkable achievement of this campaign and shows why the Austrian was so well regarded. Having taken over a battered and defeated army, he first reorganised it then ...marched 200 miles in 24 days...crossed four major rivers, pierced lines drawn between the mountains to the seas to stop him...and drove superior numbers of the enemy before him.[8]

Although outnumbered 30,000 to 42,000, the Savoyard/Imperial troops were concentrated while the French were dispersed around the city. Morale was low; Orléans and La Feuillade knew even if they captured Turin, holding it required resources needed in Flanders, while their troops had taken heavy casualties.

On 5 September, the Allied forces took up position close to Collegno, which lay between the Dora Riparia and the Stura di Lanzo rivers near a weak spot in the French lines. They launched their attack around 10:00 am on 7 September; after three failed attempts, Prussian infantry under the Prince of Anhalt-Dessau broke the French right wing and their position began to collapse.[9] Both Marsin and Orléans were wounded, Marsin fatally; the French lost 2,000 dead and 6,000 captured,[lower-alpha 4] the relief force 1,800 dead and 4,000 wounded.[10] While French positions around the rest of Turin remained intact, the siege was broken; they retreated east towards Pinerolo and Victor Amadeus re-entered his capital the same day.

Aftermath

On 8 September, a French detachment in Lombardy under the Count of Médavy defeated a Hessian corps at Castiglione but this did not affect the strategic position. Although the French still had substantial numbers of men in both Pinerolo and Susa, Victor Amadeus correctly calculated they would not conduct offensive operations. His Duchy was enlarged by the new territory of Montferrat but Nice and the County of Savoy were not returned until 1713 while Savoyard ambitions to gain Milan remained unfulfilled for another 150 years.[11]

To the fury of his Allies, in March 1707, Emperor Joseph signed the Convention of Milan with France ending the war in Italy. The French withdrew their remaining garrisons, ceding control of Milan and Mantua to Austria but given free passage to France, allowing them to be redeployed elsewhere.[12] Prince Eugene agreed to support Allied operations in Spain by attacking the French naval base at Toulon but the Austrians then diverted 10,000 troops to capture the Spanish-held Kingdom of Naples, making it the dominant power in Italy.[lower-alpha 5]

The Siege of Turin and the death of the Piedmontese hero Pietro Micca became significant parts of the history first of the Savoyard and then the Italian state. This was portrayed in the 1938 Italian film Pietro Micca. On its third centenary in 2006, a number of studies were published to mark the occasion including Le Aquile e i Gigli. Una storia mai scritta.[13]

Footnotes

- ↑ Although part of the Republic of Venice and thus technically neutral, this was ignored in practice.

- ↑ Their approach was known as the 'Coehoorn method', popularised by Vauban's rival, Dutch military engineer Menno van Coehoorn

- ↑ The Piedmontese hero Pietro Micca was killed during the second assault on 31 August.

- ↑ These figures assume most of the French wounded were left behind and captured.

- ↑ Without significant naval forces of its own, Austria could not take Sicily and both were recaptured by Spain in 1734.

References

- ↑ Frey, Linda, Frey, Marsha (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 446. ISBN 0313278849.

- ↑ Symcox, Geoffrey (1983). Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730. University of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 0520049748.

- ↑ Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714. Longman. p. 309. ISBN 0582056292.

- ↑ Symcox, Geoffrey (1983). Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730. University of California Press. p. 150. ISBN 0520049748.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (ed) (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 701. ISBN 1851096671. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ Duffy, Christopher (1985). The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great 1660-1789 (2017 ed.). Routledge. pp. 50–51. ISBN 1138924644.

- ↑ Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714. Longman. p. 309. ISBN 0582056292.

- ↑ Somerville, Thomas (1795). The History of Great Britain During the Reign of Queen Anne (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 137. ISBN 1333572379.

- ↑ Symcox, Geoffrey (1983). Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730. University of California Press. p. 151. ISBN 0520049748.

- ↑ Frey, Linda, Frey, Marsha (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 446. ISBN 0313278849.

- ↑ Symcox, Geoffrey (1983). Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730. University of California Press. pp. 152–1523. ISBN 0520049748.

- ↑ Sundstrom, Roy A (1992). Sidney Godolphin: Servant of the State. EDS Publications Ltd. p. 196. ISBN 0874134382.

- ↑ Giovanni Cerino Badone, ed. (2007). Le Aquile e i Gigli. Una storia mai scritta. Turin. ISBN 978-88-7241-512-2.

Sources

- Bevilacqua, P and Zannoni, F; "Mastri da muro e piccapietre al servizio del Duca;

- Bodart, G; Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905); (CW Stern, 1908);

- Duffy, Christopher; The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great 1660-1789; (Routledge, 2017 ed)

- Frey, Linda & Frey, Marsha; The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary; (Greenwood, 1995);

- Lynn, John; The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714; (Longman, 1999);

- Somerville, Thomas; The History of Great Britain During the Reign of Queen Anne; (Forgotten Books, 1795 2017 ed);

- Sundstrom, Roy A; Sidney Godolphin: Servant of the State; (EDS Publications Ltd, 1992);

- Symcox, Geoffrey; Victor Amadeus II: Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730; (University of California Press, 1983);

External links

- Pages about the siege (in Italian) (in English) (in German)

- Pietro Micca and Siege of Turin Museum (in Italian)