Battle of Malplaquet

The Battle of Malplaquet was a battle of the War of the Spanish Succession, fought on 11 September 1709, which opposed the Bourbons of France and Spain against an alliance whose major members were the Habsburg Monarchy, the United Provinces, Great Britain and the Kingdom of Prussia.

The Dutch-British army (the Dutch forming the vast majority of the troops) and Austrians were led by the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugène of Savoy, while the French were commanded by Marshal Villars and Marshal Boufflers. Each side had about 90,000 troops, and were encamped within cannon range of each other near the Belgian border. The Austrians attacked at 9am, pushing the French back into the forest behind them. The Dutch broke off to attack the French right flank and succeeded with heavy casualties to distract Boufflers enough so that he could not come to Villars' aid.

Villars was able to regroup his forces, but Marlborough and Eugène attacked again and forced Villars to retreat by 3pm. The Allies had suffered so many casualties in their attack that they could not pursue him. By this time they had lost 20,000 men, twice as many as the French. It was the bloodiest battle of the war, and prevented the Allies from invading northern France.

Prelude

After a late start to the campaigning season owing to the unusually harsh winter preceding it, the allied campaign of 1709 began in mid June. Unable to bring the French army under Marshal Villars to battle owing to strong French defensive lines and the Marshal's orders from Versailles not to risk battle, the Duke of Marlborough concentrated instead on taking the fortresses of Tournai and Ypres. Tournai fell after an unusually long siege of almost 70 days, by which time it was early September, and rather than run the risk of disease spreading in his army in the poorly draining land around Ypres, Marlborough instead moved eastwards towards the lesser fortress of Mons, hoping by taking it to outflank the French defensive lines in the west. Villars moved after him, under new orders from Louis XIV to prevent the fall of Mons at all costs – effectively an order for the aggressive Marshal to give battle. After several complicated manoeuvres, the two armies faced each other across the gap of Malplaquet, south-west of Mons.

Battle

The Allied army, mainly consisting of Dutch and Austrian troops, but also with considerable British and Prussian contingents, was led by the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy, while the French were commanded by Villars and Marshal Boufflers. Boufflers was officially Villars' superior but voluntarily serving under him. The allies had about 86,000 troops and 100 guns[1] and the French had about 75,000 and 80 guns,[2] and they were encamped within cannon range of each other near what is now the France/Belgium border.[3] At 9.00 am on 11 September, the Austrians attacked with the support of Prussian and Danish troops under the command of Count Albrecht Konrad Finck von Finckenstein, pushing the French left wing back into the forest behind them. Prince Eugene was wounded twice in the fighting.[4] The Dutch under command of John William Friso, Prince of Orange, on the Allied left wing, attacked the French right flank half an hour later, and succeeded with heavy casualties in distracting Boufflers enough so that he could not come to Villars' aid.

Villars was able to regroup his forces, but Marlborough and Savoy attacked again, assisted by the advance of a detachment under General Henry Withers advancing on the French left flank, forcing Villars to divert forces from his centre to confront them. At around 1.00 pm Villars was badly wounded by a musket ball which smashed his knee, and command passed to Boufflers. The decisive final attack was made on the now weakened French centre by British infantry under the command of the Earl of Orkney, which managed to occupy the French line of redans. This enabled the Allied cavalry to advance through this line and confront the French cavalry behind it. A fierce cavalry battle now ensued, in which Boufflers personally led the elite troops of the Maison du Roi. He managed six times to drive the Allied cavalry back upon the redans, but every time the French cavalry in its turn was driven back by British infantry fire. Finally, by 3.00 pm Boufflers, realising that the battle could not be won, ordered a retreat, which was made in good order. The Allies had suffered so many casualties in their attack that they could not pursue him. By this time they had lost over 24,000 men, including 6,500 killed, almost twice as many as the French.[4][5] Villars himself remarked on the enemy's Pyrrhic victory via the flip-side of King Pyrrhus' famous quote: "If it please God to give your majesty's enemies another such victory, they are ruined."[6][7]

First-hand account

A first-hand account of the Battle of Malplaquet is given in the book Amiable Renegade: The Memoirs of Peter Drake (1671–1753) on pages 163 to 170. Captain Drake, an Irishman who spent most of his life as a mercenary in the service of various European armies, served the French cause in the battle and was wounded several times. Drake wrote his memoirs at an advanced age (another Irish émigré, Féilim Ó Néill, died in the battle).

Aftermath

By the norms of warfare of the era, the battle was an allied victory, because the French withdrew at the end of the day's fighting, and left Marlborough's army in possession of the battlefield, but with double the casualties. In contrast with the Duke's previous victories, however, the French army was able to withdraw in good order and relatively intact, and remained a potent threat to further allied operations. Villars claimed that a few more such French defeats would destroy the allied armies[8] and the historian John A. Lynn in his book The Wars of Louis XIV 1667–1714 terms the battle a Pyrrhic victory,[9][10] but the attempt to save Mons failed and the fortress fell on 20 October. News of Malplaquet, the bloodiest battle of the eighteenth century, stunned Europe; a rumour abounded that even Marlborough had died.

For the last of his four great battlefield victories, the Duke of Marlborough received no personal letter of thanks from Queen Anne. Richard Blackmore's Instructions to Vander Beck was virtually alone among English poems in attempting to celebrate the "victory" of Marlborough at Malplaquet, while it moved the English Tory party to begin agitating for a withdrawal from the alliance as soon as they formed a government the next year.

Gallery

Location in modern northern France (yellow)

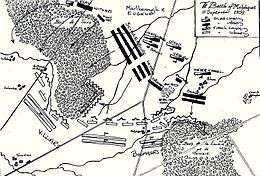

Location in modern northern France (yellow) Map of forces. Upper right: Allied. Lower left: French

Map of forces. Upper right: Allied. Lower left: French

Citations

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV 1667–1714, p. 332

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV 1667–1714, p. 331

- ↑ At the time the area was still part of the Spanish Netherlands

- 1 2 Clodfelter 2017, p. 72.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV 1667–1714, p. 334

- ↑

- ↑ Weir, p. 95

- ↑ In a letter to Louis XIV, Villars wrote: "Si Dieu nous fait la grâce de perdre encore une pareille bataille, Votre Majesté peut compter que tous ses ennemis seront détruits." ["If God gives us the grace of losing such a battle again, Your Majesty may expect that all his enemies will be destroyed."]; Anquetil, Louis-Pierre, Histoire de France depuis les Gaulois jusqu'à la mort de Louis XVI (1819), Paris: Chez Janet et Cotelle, p. 241.

- ↑ Lynn, 1999, p. 334: "Marlborough's triumph proved to be a Pyrrhic victory".

- ↑ Delbrück, History of the Art of War, p. 370: "Malplaquet was what has been termed with the age-old expression a "Pyrrhic victory..."

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Malplaquet. |

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Delbrück, Hans (1985). History of the Art of War, Volume IV: The Dawn of Modern Warfare. Translated by Renfroe, Walter J. Eastport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 0-8032-6586-7.

- Drake, Peter (1960). Amiable Renegade: The Memoirs of Captain Peter Drake (1671–1753). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804700222.

- Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-05629-2.

- Weir, William (2006) [1993]. Fatal Victories. New York: Pegasus. ISBN 1933648120.