Sex differences in education

| This article is one of a series on: |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

| Physiology |

| Medicine |

| Neuroscience |

| Sociology |

Sex differences in education are a type of sex discrimination in the education system affecting both men and women during and after their educational experiences.[1] Men are more likely to be literate on a global average, although women are more prevalent at in some countries.[2] Men and women find themselves having gender differences when attaining their educational attainments. Although men and women can have the same level of education, it is more difficult for women to have higher management jobs, and future employment and financial worries can intensify.[3][4] Men tended to received more education than women in the past, but the gender gap in education has reversed in recent decades in most Western countries and many non-Western countries.[5]

Statistics

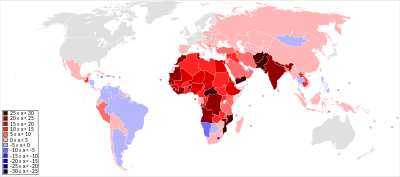

Worldwide, men are more likely to be literate, with 100 men considered literate for every 88 women. In some countries the difference is even greater; for example, in Bangladesh only 62 women are literate for every 100 men.[6]

In an OECD study of 43 developed countries, 15-year-old girls were ahead of boys in literacy skills and were more confident than boys about getting high-income jobs.. In the United States, girls are significantly ahead of boys in writing ability at all levels of primary and secondary education.[7] However, boys are slightly ahead of girls in mathematics ability.[8]

Female majority

In the US, the 2005 averages of male and female university participants were pegged at a 43-to-57 ratio.[9] Also, in 2005-2006, women earned more Associate's, Bachelor's, and master's degrees than men and earned 48.9% of Doctorate and 49.8% of first professional degrees.[10] This is repeated in other countries; for example, women make up 58% of admissions in the UK[11] and 60% in Iran. In Canada the 15% gender gap in university participation favored women.[12]

Inequalities in Education around the World

Source[13]

| Country | Mean Years of Schooling, Female (2017) | Mean Years of Schooling, Male (2017) | Population (%) with at least some Secondary Education, Female 25+ (2017) | Population (%) with at least some Secondary Education, Male 25+ (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 1.9 | 6 | 11.4 | 36.9 |

| Albania | 9.8 | 10.2 | 93.1 | 92.8 |

| Algeria | 7.6 | 8.6 | 37.5 | 37.9 |

| Andorra | 10.1 | 10.2 | 71.7 | 73.3 |

| Argentina | 10.1 | 9.7 | 65.9 | 62.8 |

| Armenia | 11.7 | 11.7 | 96.9 | 97.6 |

| Australia | 12.9 | 12.8 | 90 | 89.9 |

| Austria | 11.8 | 12.6 | 100 | 100 |

| Azerbaijan | 10.4 | 11 | 93.8 | 97.5 |

| Bahamas | 11.5 | 10.5 | 87.4 | 87.6 |

| Bahrain | 9.3 | 9.5 | 63.7 | 57.1 |

| Bangladesh | 5.2 | 6.7 | 44 | 48.2 |

| Barbados | 10.6 | 10.4 | 94.2 | 91.6 |

| Belarus | 12.2 | 12.4 | 87 | 92.2 |

| Belgium | 11.6 | 11.9 | 82.2 | 86.7 |

| Belize | 10.5 | 10.4 | 78.9 | 78.4 |

| Benin | 3 | 4.3 | 18.2 | 32.7 |

| Bhutan | 2.1 | 4.2 | 6 | 13.7 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 8.2 | 9.7 | 50.5 | 59.5 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 8.6 | 10.9 | 71.7 | 88.7 |

| Botswana | 9.2 | 9.5 | 88.8 | 89.6 |

| Brazil | 8 | 7.7 | 61 | 57.7 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 9 | 9.1 | 69.1 | 70.3 |

| Bulgaria | 11.9 | 11.8 | 93.7 | 96.1 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | 2 | 6 | 11.7 |

| Burundi | 2.7 | 3.7 | 7.5 | 10.5 |

| Cabo Verde | 5.9 | 6.4 | ||

| Cambodia | 3.8 | 5.6 | 15.1 | 28.1 |

| Cameroon | 4.7 | 7.6 | 32.5 | 39.2 |

| Canada | 13.3 | 12.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Central African Republic | 3 | 5.6 | 13.2 | 30.8 |

| Chad | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 10 |

| Chile | 10.2 | 10.5 | 79 | 80.9 |

| China | 7.6 | 8.3 | 74 | 82 |

| Colombia | 8.5 | 8.1 | 51.1 | 49.2 |

| Comoros | 3.7 | 5.6 | ||

| Congo | 5.5 | 6.7 | 46.7 | 51 |

| Congo (Democratic Republic of the) | 5.3 | 8.4 | 36.7 | 65.8 |

| Costa Rica | 8.8 | 8.5 | 53.8 | 51.9 |

| Croatia | 11.2 | 11.7 | 94.5 | 96.9 |

| Cuba | 11.6 | 12.1 | 86.7 | 88.9 |

| Cyprus | 12 | 12.2 | 76.8 | 80.7 |

| Czechia | 12.6 | 13.1 | 99.8 | 99.8 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 4 | 6.2 | 17.8 | 34.1 |

| Denmark | 12.7 | 12.4 | 90.1 | 91.3 |

| Dominican Republic | 8.1 | 7.5 | 58.6 | 54.4 |

| Ecuador | 8.6 | 8.8 | 52.1 | 52.2 |

| Egypt | 6.5 | 7.9 | 58.2 | 70.7 |

| El Salvador | 6.7 | 7.3 | 42.2 | 47.9 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 4 | 7.3 | ||

| Estonia | 13 | 12.2 | 100 | 100 |

| Eswatini (Kingdom of) | 6.1 | 6.9 | 30 | 32.7 |

| Ethiopia | 1.6 | 3.8 | 11.2 | 21.4 |

| Fiji | 10.9 | 10.7 | 77.3 | 68.3 |

| Finland | 12.6 | 12.3 | 100 | 100 |

| France | 11.3 | 11.8 | 80.6 | 85.6 |

| Gabon | 7.4 | 9.1 | 65.6 | 49.8 |

| Gambia | 2.9 | 4.3 | 29 | 42.3 |

| Georgia | 12.8 | 12.8 | 95.1 | 96 |

| Germany | 13.6 | 14.5 | 96.2 | 96.8 |

| Ghana | 6.3 | 7.9 | 54.6 | 70.4 |

| Greece | 10.5 | 11 | 65.4 | 73.2 |

| Guatemala | 6.4 | 6.5 | 38.4 | 37.2 |

| Guinea | 1.5 | 3.9 | ||

| Guyana | 8.4 | 8.4 | 70.9 | 55.5 |

| Haiti | 4.3 | 6.6 | 26.9 | 39.9 |

| Honduras | 6.6 | 6.5 | 36.8 | 33.5 |

| Hong Kong, China (SAR) | 11.6 | 12.5 | 75.7 | 81.8 |

| Hungary | 11.7 | 12.1 | 95.7 | 98 |

| Iceland | 12.3 | 12.7 | 100 | 100 |

| India | 4.8 | 8.2 | 39 | 63.5 |

| Indonesia | 7.5 | 8.4 | 44.5 | 53.2 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 9.7 | 9.9 | 65.8 | 70.9 |

| Iraq | 5.4 | 7.8 | 38.7 | 56.7 |

| Ireland | 12.7 | 12.1 | 90.2 | 86.3 |

| Israel | 13 | 13 | 87.8 | 90.5 |

| Italy | 10 | 10.4 | 75.6 | 83 |

| Jamaica | 10 | 9.5 | 69.9 | 62.4 |

| Japan | 12.9 | 12.5 | 94.8 | 91.9 |

| Jordan | 10.1 | 10.6 | 81.4 | 85.8 |

| Kazakhstan | 11.8 | 11.7 | 98.5 | 99.1 |

| Kenya | 5.7 | 7.1 | 29.2 | 36.6 |

| Korea (Republic of) | 11.4 | 12.9 | 89.8 | 95.6 |

| Kuwait | 8 | 6.9 | 54.8 | 49.3 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 10.9 | 10.8 | 98.6 | 98.3 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 4.6 | 5.7 | 33.6 | 45.2 |

| Latvia | 13.2 | 12.5 | 99.4 | 99.1 |

| Lebanon | 8.5 | 8.9 | 53 | 55.4 |

| Lesotho | 7 | 5.5 | 31.8 | 24.2 |

| Liberia | 3.5 | 6.1 | 18.5 | 39.6 |

| Libya | 7.7 | 7 | 69.4 | 45 |

| Lithuania | 13 | 13 | 91.8 | 96.4 |

| Luxembourg | 11.7 | 12.4 | 100 | 100 |

| Madagascar | 6.7 | 6.1 | ||

| Malawi | 4 | 5.1 | 16.7 | 25.4 |

| Malaysia | 10 | 10.3 | 78.9 | 81.3 |

| Maldives | 6.2 | 6.4 | 44.9 | 49.3 |

| Mali | 1.7 | 3 | 7.3 | 16.4 |

| Malta | 11 | 11.6 | 73.2 | 82 |

| Marshall Islands | 10.7 | 11.1 | 91.6 | 92.5 |

| Mauritania | 3.5 | 5.5 | 12.2 | 24.5 |

| Mauritius | 9.1 | 9.5 | 64.3 | 67.3 |

| Mexico | 8.4 | 8.8 | 57.8 | 61 |

| Moldova (Republic of) | 11.5 | 11.7 | 95.5 | 97.4 |

| Mongolia | 10.6 | 9.8 | 91.2 | 86.3 |

| Montenegro | 10.7 | 12 | 87 | 96.4 |

| Morocco | 4.5 | 6.5 | 28 | 34.8 |

| Mozambique | 2.5 | 4.6 | 16.1 | 27.3 |

| Myanmar | 4.9 | 4.8 | 28.7 | 22.3 |

| Namibia | 7.2 | 6.6 | 39.9 | 41 |

| Nepal | 3.6 | 6.4 | 27.3 | 43.1 |

| Netherlands | 11.9 | 12.5 | 86.4 | 90.4 |

| New Zealand | 12.7 | 12.5 | 99 | 98.8 |

| Nicaragua | 6.9 | 6.4 | 48.3 | 46.6 |

| Niger | 1.5 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 8.9 |

| Nigeria | 5 | 7.3 | ||

| Norway | 12.6 | 12.5 | 96.3 | 95.1 |

| Oman | 10.4 | 9.2 | 73.5 | 63.7 |

| Pakistan | 3.8 | 6.5 | 27 | 47.3 |

| Palestine, State of | 8.9 | 9.3 | 58.5 | 62.3 |

| Panama | 10.4 | 9.9 | 72.7 | 68.4 |

| Papua New Guinea | 3.8 | 5.3 | 9.5 | 15 |

| Paraguay | 8.4 | 8.3 | 47 | 49.2 |

| Peru | 8.7 | 9.7 | 57.1 | 67.5 |

| Philippines | 9.5 | 9.2 | 76.6 | 72.4 |

| Poland | 12.3 | 12.3 | 81.1 | 86.9 |

| Portugal | 9.2 | 9.2 | 52.1 | 53.4 |

| Qatar | 10.8 | 9.5 | 70.9 | 68 |

| Romania | 10.6 | 11.3 | 86.5 | 92.7 |

| Russian Federation | 12 | 12.1 | 95.8 | 95.3 |

| Rwanda | 3.7 | 4.7 | 12.6 | 17 |

| Saint Lucia | 9.4 | 8.7 | 48.2 | 42 |

| Samoa | 79.1 | 71.6 | ||

| Sao Tome and Principe | 5.6 | 7.1 | 31.1 | 45.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 8.8 | 9.9 | 67.8 | 75.5 |

| Senegal | 2.4 | 3.8 | 11.1 | 20.1 |

| Serbia | 10.7 | 11.6 | 84.6 | 93 |

| Sierra Leone | 2.7 | 4.3 | 19.2 | 32.3 |

| Singapore | 11 | 12.1 | 76.1 | 82.9 |

| Slovakia | 12.3 | 12.6 | 99.1 | 100 |

| Slovenia | 12.2 | 12.3 | 97.4 | 98.9 |

| South Africa | 9.9 | 10.4 | 74.2 | 77.4 |

| South Sudan | 4 | 5.3 | ||

| Spain | 9.7 | 10 | 72.2 | 77.6 |

| Sri Lanka | 10.3 | 11.4 | 82.6 | 83.1 |

| Sudan | 3.1 | 4.1 | 14.7 | 19.3 |

| Suriname | 8.3 | 8.6 | 58.7 | 57.8 |

| Sweden | 12.5 | 12.3 | 88.4 | 88.7 |

| Switzerland | 13.9 | 12.9 | 96.4 | 97.2 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 4.6 | 5.6 | 37.1 | 42.6 |

| Tajikistan | 10.7 | 10.2 | 98.9 | 87 |

| Tanzania (United Republic of) | 5.4 | 6.2 | 11.9 | 16.9 |

| Thailand | 7.4 | 7.8 | 42.4 | 47.5 |

| The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | 8.9 | 9.9 | 40.5 | 56 |

| Timor-Leste | 3.6 | 5.3 | ||

| Togo | 3.3 | 6.5 | 26.3 | 52.5 |

| Tonga | 11.2 | 11.1 | 92.7 | 92.3 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 11 | 10.8 | 74.4 | 69.1 |

| Tunisia | 6.3 | 7.9 | 41.2 | 52.7 |

| Turkey | 7.1 | 8.8 | 44.9 | 66 |

| Uganda | 4.7 | 7.2 | 26.7 | 32.4 |

| Ukraine | 11.3 | 11.3 | 94.5 | 95.6 |

| United Arab Emirates | 11.9 | 9.7 | 78.8 | 65.7 |

| United Kingdom | 12.8 | 13.5 | 82.4 | 85.2 |

| United States | 13.4 | 13.3 | 95.5 | 95.2 |

| Uruguay | 9 | 8.4 | 55.8 | 52.1 |

| Uzbekistan | 11.2 | 11.8 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 10.7 | 10 | 71.7 | 66.6 |

| Viet Nam | 7.9 | 8.5 | 66.2 | 77.7 |

| Yemen | 1.9 | 4.2 | 18.7 | 34.8 |

| Zambia | 6.5 | 7.4 | 39.2 | 52.4 |

| Zimbabwe | 7.5 | 8.9 | 55.9 | 66.3 |

Forms of sex discrimination in education

Sex discrimination in education is applied to women in several ways. First, many sociologists of education view the educational system as an institution of social and cultural reproduction .[14]The existing patterns of inequality, especially for gender inequality, are reproduced within schools through formal and informal processes.[1] In Western societies, these processes can be traced all the way back to preschool and elementary school learning stages. Research such as May Ling Halim et al.’s 2013 study has shown that children are aware of gender role stereotypes from a young age, with those who are exposed to higher levels of media, as well as gender stereotyped behavior from adults holding the strongest perception of gender stereotypical roles, regardless of ethnicity.[15] Indeed, Sandra Bem’s gender schema theory identifies that children absorb gender stereotypes by observing the behavior of humans around them and then imitate the actions of those they deem to be of their own gender.[16] Thus, if children attain gender cues from environmental stimuli, it stands to reason that the early years of a child’s education are some of the most formative for developing ideas about gender identity and can potentially be responsible for reinforcing harmful notions of disparity in the roles of males and females. Jenny Rodgers identifies that gender stereotypes exist in a number of forms in the primary classroom, including the generalization of attainment levels based upon sex and teacher attitudes towards gender appropriate play.[17]

Hidden curriculum

In her 1978 quantitative study, Katherine Clarricoates conducted field observations and interviews with British primary school teachers from a range of schools located in both rural and urban and wealthy and less wealthy areas.[18] Her study confirms that Rodgers’ assertions about gender stereotypes and discrimination were widely seen in the classrooms. In an extract from one of the interviews, a teacher claimed that it is “subjects like geography…where the lads do come out…they have got the facts whereas the girls tend to be a bit more woollier in most of the things”. [19] Meanwhile other teachers claimed that “they (girls) haven’t got the imagination that most of the lads have got” and that “I find you can spark the boys a bit easier than you can the girls…Girls have got their own set ideas – it’s always ‘…and we went home for tea’… Whereas you can get the boys to write something really interesting…”. [19] In another interview, a teacher perceived gender behavioral differences, remarking “…the girls seem to be typically feminine whilst the boys seem to be typically male…you know, more aggressive... the ideal of what males ought to be”, [20] while another categorized boys as more “aggressive, more adventurous than girls”. [21] When considering Bem’s gender schema theory in relation to these statements, it is not difficult to see how male and female pupils may pick up various behavioral cues from their teachers’ gender differentiation and generalizations which then manifest themselves in gendered educational interests and levels of attainment. Clarricoates terms this bias the “hidden curriculum” as it is deviant from the official curriculum which does not discriminate based on gender. [22] She notes that it arises from a teacher’s own underlying beliefs about gendered behavior and causes them to act in favor of the boys but to the detriment of the girl pupils. This ultimately leads to the unfolding of a self-fulfilling prophecy in the academic and behavioral performances of the students.[23] Citing Patricia Pivnick’s 1974 dissertation on American primary schools, Clarricoates posits that

- It is possible that by using a harsher tone for controlling the behavior of boys than for girls, the teachers actually foster the independent and defiant spirit which is considered ‘masculine’ in our culture…At the same time, the ‘femininity’ which the teachers reinforced in girls may foster the narcissism and passivity which results in lack of motivation and achievement in girls.[24]

This analysis highlights the lifelong hinderances that the “hidden curriculum” of teachers can inflict on both genders.

Linguistic sexism

Another element of the “hidden curriculum” Clarricoates identifies is linguistic sexism. She defines this term as the consistent and unconscious use of words and grammatical forms by teachers that denigrate women and emphasize the assumed superiority of men, not only in lesson content but also in situations of disciplinary procedure. [21] One example of this she cites is the gendering of animal and inanimate characters. She states that teachers, together with TV presenters and characters as well as curricular materials all refer to dinosaurs, pandas, squirrels and mathematical characters as “he”, conveying to young children that these animals all only come in the male gender. Meanwhile, only motherly figures such as ladybirds, cows and hens are referred to as “she”. As a result, school books, media and curriculum content all give students the impression that females do not create history which contributes to the damaging assumption that females cannot transform the world, whereas men can. [21]

In addition, Clarricoates discusses the linguistic sexism inherent to the adjective choice of teachers when admonishing or rewarding their pupils. She notes that “if boys get out of hand they are regarded as ‘boisterous’, ‘rough’, ‘assertive’, ‘rowdy’ and ‘adventurous’”, whereas girls were referred to as “‘fussy’, ‘bitchy’, giggly’, ‘catty’ and ‘silly’”. According to Clarricoates' previously stated observations, the terms applied to boys imply positive masculine behavior, meanwhile the categories used for girls are more derogatory.[21] This difference in teachers’ reactions to similar behaviors can again be seen as contributing to the development of gender stereotyped behaviors in young pupils. Another element of linguistic sexism that Clarricoates identifies is the difference in the treatment of male and female pupils’ use of “improper language” by their teachers; girls tended to be censured more harshly compared to boys, due to unconscious biases about gender appropriate behavior. While girls were deemed as “unladylike” for using “rough” speech, the same speech uttered by their male counterparts was regarded as a part of normal masculine behavior, and they were thus admonished less harshly. This creates a linguistic double standard which can again be seen to contribute to long-term gender disparities in behavior. [21]

Clarricoates concludes her study by observing that there is a “catch 22” situation for young female pupils. If a girl conforms to institutional ideals by learning her lessons well, speaking appropriately and not bothering the teacher then her success is downplayed in comparison to the equivalent behavior in a male pupil. Indeed, she is regarded as “passive”, or a “goody-goody” and as “lesser” than her male pupils. As a result, this reinforcement will foster submissiveness and self-depreciation; qualities which society does not hold in great esteem. However, if she does not conform then she will be admonished more harshly than her equivalent male pupils and also be viewed in a more negative light. She will be regarded as problematic and disruptive to the class, which may ultimately impact her academic performance and career prospects in the future. Furthermore, if she is able to survive the school institution as an assertive and confident individual then she will still face many challenges in the workplace, where these characteristics in women are often perceived as “bossy” or “overbearing”. [25]

Dominance of heteronormativity

Rodgers identifies that another challenge to gender equality in the elementary school classroom is the dominance of heteronormativity and heterosexual stereotypes. Citing the research of Guasp, she maintains that heteronormative discourse still remains the norm, both in schools and in wider western society.[26][27] She notes that gender and heterosexual stereotypes are intrinsically linked, due to expectations of females being sexually attracted to males and vice versa, as part of their gender performance. Thus, one of the major challenges to gender equality is the concealment of sexual diversity under the dominance of heteronormativity. [28] Rodgers identifies that although the 1988 Education Reform Act in the United Kingdom helped to increase opportunities for gender diversity by ensuring that both sexes study the same core subjects, on the other hand, heterosexual stereotyping was exacerbated by the passing of Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which decreed homosexuality “as a pretended family relationship.” This caused a significant hinderance in the widespread acceptance of homosexuality and thus, the progression of gender equality in schools. [29] Despite the 2003 repeal of this act, [30] the pupils most at risk of discrimination as a result of gender biases in the “hidden curriculum”, are still those who do not conform to gender and heterosexual stereotypes. Indeed, Rodgers cites these teaching approaches as conforming to hegemonic masculinity, and attributes this method to the marginalization of students who do not conform to their stereotypical gender roles. [29]

Another way the educational system discriminates towards females is through course-taking, especially in high school. This is important because course-taking represents a large gender gap in what courses males and females take, which leads to different educational and occupational paths between males and females. For example, females tend to take fewer advanced mathematical and scientific courses, thus leading them to be ill-equipped to pursue these careers in higher education. This can further be seen in technology and computer courses.[1]

Cultural norms may also be a factor causing sex discrimination in education. For example, society suggests that women should be mothers and responsible for the bulk of child rearing. Therefore, women feel compelled to pursue educational pathways that lead to occupations that allow for long leaves of absence, so they can be stay-at-home mothers.[1] Child marriages can be another determining factor in ending the formal education and literacy rates of women in various parts of the world.[31] According to research conducted by UNICEF in 2013, one out of three girls across the developing world is married before the age of 18.[32] As an accepted practice in many cultures, the investment in a girl's education is given little importance, whereas emphasis is placed on men and boys to be the 'breadwinners.'[33]

A hidden curriculum may further add to discrimination in the educational system. Hidden curriculum is the idea that race, class, and gender have an influence on the lessons that are taught in schools.[34] Moreover, it is the idea that certain values and norms are instilled through curriculum. For example, U.S. history often emphasizes the significant roles that white males played in the development of the country. Some curriculum have even been rewritten to highlight the roles played by white males. An example of this would be the way wars are talked about. Curriculum's on the Civil War, for instance, tend to emphasize the key players as Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, and Abraham Lincoln. Whereas woman or men of color such as Harriet Tubman as a spy for the Union, Harriet Beecher Stowe or Frederick Douglass, are downplayed from their part in the war.[35] Another part is that the topics being taught are masculine or feminine. Shop classes and advanced sciences are seen as more masculine, whereas home economics, art, or humanities are seen as more feminine. The problem comes when students receive different treatment and education because of his or her gender or race.[35] Students may also be socialized for their expected adult roles through the correspondence principle laid out by sociologists including Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis. Girls may be encouraged to learn skills valued in female-dominated fields, while boys might learn leadership skills for male-dominated occupations. For example, as they move into the secondary and post-secondary phases of their education, boys tend to gravitate more toward STEM courses than their female classmates.[36]

Consequences of sex discrimination in education

Discrimination results for the most part, being in low status, sex-stereotyped occupations, which in part is due to gender differences in majors.[37] They also have to endure the main responsibilities of domestic tasks, even though their labor force participation has increased. Sex discrimination in high school and college course-taking also results in women not being prepared or qualified to pursue more prestigious, high paying occupations. Sex discrimination in education also results in women being more passive, quiet, and less assertive, due to the effects of the hidden curriculum.[1]

However, in 2005, USA Today reported that the "college gender gap" was widening, stating that 57% of U.S. college students are female.[38] This gap has been gradually widening, and as of 2014, almost 45% of women had a bachelor's degree, compared to 32% of men with a bachelor's degree.[39]

Classroom interactions can also have unseen consequences. Because gender is something we learn, day-to-day interactions shape our understandings of how to do gender.[34] Teachers and staff in an elementary may reinforce certain gender roles without thinking. Their communicative interactions may also single out other students. For example, a teacher may call on one or two students more than the others. This causes those who are called on less to be less confidant. A gendered example would be a teacher expecting a girl to be good at coloring or a boy to be good at building. These types of interactions restrict a student to the particular role assigned to them.[35]

Other consequences come in the form of what is communicated as appropriate behaviors for boys and girls in classes like physical education. While a teacher may not purposely try to communicate these differences, they may tend to make comments based on gender physical ability.[40] For example, a male may be told that he throws like a girl which perpetuates him to become more masculine and use brute force. A female, on the other hand, might be told she is too masculine looking to where she becomes more reserved and less motivated.[41]

Some gender discrimination, whether intentional or not, also effects the positions students may strive for in the future. Females may not find interest in science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM), because they have not been exposed to those types of classes. This is because interactions within the school and society are pushing them towards easier, more feminine classes, such as home economics or art. They also might not see many other women going into the STEM field. This then lowers the number of women in STEM, further producing and continuing this cycle.[42] This also has a similar effect on males. Because of interactions from teachers, such as saying boys do not usually cook, males may then be less likely to follow careers such as a chef, an artist, or a writer.[41]

Since the 1990s, enrollment on university campuses across Canada has risen significantly. Most notable is the soaring rates of female participants, which has surpassed the enrollment and participation rates of their male counterparts.[12] Even in the United States, there is a significant difference in the male to female ratio in campuses across the country, where the 2005 averages saw male to female university participants at 43 to 57.[9] Although it is important to note that the rates of both sexes participating in post-secondary studies is increasing, it is equally important to question why female rates are increasing more rapidly than male participation rates. Christofides, Hoy, and Yang study the 15% male to female gap in Canadian universities with the idea of the University Premium.[12] Drolet further explains this phenomenon in his 2007 article, "Minding the Gender Gap": "A university degree has a greater payback for women relative to what they could have earned if they only had a high-school diploma because men traditionally have had more options for jobs that pay well even without post-secondary education."[43]

Gender gap in literacy

Critics of the gender gap in education often focus on the advantage males have over females in science and math, but fail to recognize the falling behind of males to females in literacy. In fact, the latest national test scores, collected by the NAEP assessment, show that girls have met or exceeded the reading performance of boys at all age levels. The literacy gap in fourth grade is equivalent to males being developmentally two years behind the average girl in reading and writing. At the middle school level, statistics from the Educational Testing Service show that the gap between eight-grade males and females is more than six times greater than the differences in mathematical reasoning, mathematical reasoning favoring males. These findings have spanned across the globe as the International Association for Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) found gender to be the most powerful predictor of performance in a study of 14 countries.[44]

Studies have attributed these disparities to several main factors. First of these is an innate difference in the brain function of males and females. Females have the advantage in their left hemisphere with speaking, reading and writing. Their right hemisphere allows females to feel empathy and to better understand and reflect on their feelings and the feelings of others. Both hemispheres are actively contributing to necessary literacy practices. On the other hand, boys use their left hemisphere to recall facts and rules and to categorize, while their right-hemisphere is used with visual-spatial and visual-motor skills, which enables them to excel in topics like geography, science, and math. Additionally hindering literacy instruction for males is an unwritten "Boy Code" society has placed on males keeping them from feeling and/or expressing their emotions. Males are therefore less likely to share opinions about literature and less likely to express to a teacher when having difficulty, feeling frustrated or just plain not understanding the material. Instead, males fidget, get distracted, receive reprimands, and often quit altogether.[45]

Booth, Johns, and Bruce state that at both national and international levels "male students do not do as well as girls in reading and writing and appear more often in special education classes, dropout rates and are less likely to go to university".[46][47] Boys face a multitude of difficulties when it comes to literacy and the article lists some of the possible areas of literacy education where these difficulties could stem from. These include, but are not limited to, their own gender identity, social and cultural issues, religion, technology, school cultures, teaching styles, curriculum, and the failures of pre-service and in-service teaching courses.[1]

It is also important to consider two aspects of boys and literacy education as raised in the Booth article, which draws from the 2002 work of Smith and Wilhelm. The first is achievement; boys typically take longer to learn than girls do, although they excel over females when it comes to "information retrieval and work-related literacy tasks".[48] It is important, therefore, for the teacher to provide the appropriate activities to highlight boys' strengths in literacy and properly support their weaknesses. Also, boys tend to read less than girls in their free time. This could play a role in the fact that girls typically "comprehend narrative and expository texts better than boys do".[48] In his 2009 book Grown Up Digital, Tapscott writes that there are other methods to consider in order to reach boys when it comes to literacy: "Boys tend to be able to read visual images better... study from California State University (Hayword) saw test scores increase by 11 to 16% when teaching methods were changed to incorporate more images".[49] Smith and Wilhelm say that boys typically have a "lower estimation of their reading abilities" than girls do.[48]

Possible solutions and implementation

One attempted change made to literacy instruction has been the offering of choice in classroom gender populations. In Hamilton, Ontario, Cecil B. Stirling Elementary/Junior School offered students in grades 7 and 8, and their parents, a choice between enrolling in a boys-only, girls-only or co-ed literacy course. Single-gender classes were most popular, and although no specific studies have shown a statistical advantage to single-gender literacy classes, the overall reaction by boys was positive: "I like that there's no girls and you can't be distracted. [. . .] You get better marks and you can concentrate more."[50] However a 2014 meta-analysis based on 84 studies representing the testing of 1.6 million students in Grades K-12 from 21 nations published in the journal of Psychological Bulletin, found no evidence that the view single sex schooling is beneficial over co-gendered schools.[51]

With boys-only classrooms not always being possible, it then becomes the responsibility of the literacy instructor to broaden the definition of literacy from fiction-rich literacy programs to expose students to a variety of texts including factual and nonfiction texts (magazines, informational texts, etc.) that boys are already often reading; provide interest and choice in literacy instruction; expand literacy teaching styles to more hands-on, interactive and problem-solving learning, appealing to a boy's strengths; and to provide a supportive classroom environment, sensitive to the individual learning pace of each boy and providing of a sense of competence.[44]

Other everyday practices that attempt to "close the gender gap" of literacy in the classroom can include:[45]

- Tapping into visual-spatial strengths of boys. (Filmstrips/Comics)

- Using hands-on materials. (Websites, handouts)

- Incorporating technology. (Computer Learning Games, Cyberhunts)

- Allowing time for movement. (Reader's Theaters and plays, "Active" Mnemonics)

- Allowing opportunities for competition. (Spelling Bees, Jeopardy, Hangman)

- Choosing books that appeal to boys. ("Boy's Rack" in Classroom Library)

- Providing male role models. (High-school Boys Tutoring Younger Boys in Reading, Reading/Speaking Guests)

- Boys-only reading programs. (Boys-only Book Club)

The gender gap and homeschooled children

Schools are not philosophical, social or cultural vacuums. The social structure of many schools do not produce adequate results for many boys. Many parents who home school their children observe that there is a smaller gender divide in academic test results. One study by the HSLDA revealed homeschooled boys (87th percentile) and girls (88th percentile) scored equally well. Racial disparity and disparity based on socioeconomic background is also less pronounced. A major factor in student achievement is whether a parent had attained a tertiary education.[52]

Sex differences in academics

A 2014 meta-analysis of sex differences in scholastic achievement published in the journal of Psychological Bulletin found females outperformed males in teacher-assigned school marks throughout elementary, junior/middle, high school and at both undergraduate and graduate university level.[53] The meta-analysis done by researchers Daniel Voyer and Susan D. Voyerwas from the University of New Brunswick drew from 97 years of 502 effect sizes and 369 samples stemming from the year 1914 to 2011, and found that the magnitude of higher female performance was not affected by year of publication, thereby contradicted recent claims of “boy crisis” in school achievement.[53] Another 2015 study by researchers Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary from the journal of Intelligence found that girl's overall education achievement is better in 70 percent of all the 47-75 countries that participated in PISA.[54] The study consisting of 1.5 million 15-year-olds found higher overall female achievement across reading, mathematics, and science literacy and better performance across 70% of participating countries, including many with considerable gaps in economic and political equality, and they fell behind in only 4% of countries.[54] In summary, Stoet and Geary said that sex differences in educational achievement are not reliably linked to gender equality.[54]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pearson, Jennifer. "Gender, Education and." Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Ritzer, George (ed). Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Blackwell Reference Online. 31 March 2008 <http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9781405124331_chunk_g978140512433113_ss1-16>

- ↑ Davies, Bronwyn (2007). "Gender economies: literacy and the gendered production of neo-liberal subjectivities". Gender and Education. 19.1: 1–20. doi:10.1080/09540250601087710.

- ↑ Grummel, Bernie (2009). "The care-less manager: Gender, care, and new managerialism in higher education". Gender and Education. 21.2: 191–208. doi:10.1080/09540250802392273.

- ↑ Cullen, Deborah L (2003). "Women mentoring in academe: Addressing the gender gap in higher education". Gender and Education. 5.2: 125–137.

- ↑ Van Bavel, Jan; Schwartz, Christine R.; Esteve, Albert (2018-05-16). "The Reversal of the Gender Gap in Education and its Consequences for Family Life". Annual Review of Sociology. 44 (1). doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041215. ISSN 0360-0572.

- ↑ "Illiteracy 'hinders world's poor'". BBC News. 9 November 2005. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Percentage of students attaining writing achievement levels, by grade level and selected student characteristics: 2002

- ↑ Average mathematics scale scores of 4th-, 8th-, and 12th-graders, by selected student and parent characteristics and school type: 2000, 2003, and 2005

- 1 2 Marklein, Mary Beth (19 October 2005). "College gender gap widens: 57% are women". USA Today. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Historical summary of faculty, students, degrees, and finances in degree-granting institutions: Selected years, 1869-70 through 2005-06

- ↑ Berliner, Wendy (17 May 2004). "Where have all the young men gone?". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Christofides, Louis N.; Hoy, Michael; Yang, Ling (2009). "The Determinants of University Participation in Canada (1977–2003)". Canadian Journal of Higher Education. 39 (2): 1–24.

- ↑ "Human Development Data (1990-2017) | Human Development Reports". www.hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ↑ Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (Vol. 4). Sage.

- ↑ Halim, May Ling (2013). "Four-year-olds' Beliefs About How Others Regard Males and Females". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 31 (1): 128–135. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835x.2012.02084.x.

- ↑ Bem, Sandra (1981). "Gender Schema Theory: A Cognitive Account of Sex Typing". Psychological Review. 88 (4): 354–364. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.88.4.354.

- ↑ Rodgers, Jenny (2014). "Aspirational Practice: Gender Equality The challenge of gender and heterosexual stereotypes in primary Education". The STeP Journal. 1 (1): 58–68.

- ↑ Clarricoates, Katherine (1978). "'Dinosaurs in the Classroom'--A Re-examination of Some Aspects of the 'Hidden' Curriculum in Primary Schools". Women’s Studies International Quarterly. 1: 353–364. doi:10.1016/s0148-0685(78)91245-9.

- 1 2 Clarricoates 1978, p. 357.

- ↑ Clarricoates 1978, p. 355.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clarricoates 1978, p. 360.

- ↑ Clarricoates 1978, p. 353.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Robert; Jacobsen, Lenore (1968). Pygmalion in the Classroom. London: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- ↑ Pivnick, Patricia (1974). "Sex Role Socialisation: Observations in a First Grade Classroom (It's Hard to Change Your Image Once You're Typecast)". Thesis of Doctorate of Education at the University of Rochester: 159.

- ↑ Clarricoates 1978, p. 363.

- ↑ Guasp, April (2009). Homophobic Bullying in Britain’s Schools: The Teachers’ Report. London: Stonewall.

- ↑ Guasp, April (2009). Different Families: The Experiences of Children with Lesbian and Gay Parents. London: Stonewall.

- ↑ Rodgers 2014, p. 59.

- 1 2 Rodgers 2014, p. 61.

- ↑ Rodgers 2014, p. 60.

- ↑ Psaki, S. Prospects (2016) 46: 109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-016-9379-0

- ↑ McCleary-Sills, Jennifer, et al. "Child Marriage: A Critical Barrier to Girls' Schooling and Gender Equality in Education." The Review of Faith & International Affairs, vol. 13, no. 3, 2015, pp. 69-80.

- ↑ Zuo, Jiping, and Shengming Tang. “Breadwinner Status and Gender Ideologies of Men and Women Regarding Family Roles.” Sociological Perspectives, vol. 43, no. 1, 2000, pp. 29–43. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1389781.

- 1 2 Esposito, Jennifer (2011). "Negotiating the gaze and learning the hidden curriculum: a critical race analysis of the embodiment of female students of color at a predominantly white institution". Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies.

- 1 2 3 DeFrancisco, Victoria P. (2014). Gender in Communication. Los Angeles: Sage. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-1-4522-2009-3.

- ↑ Kevin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. (2009) Educational Psychology 2nd Edition. "Chapter 4: Student Diversity." pp. 73

- ↑ Jacobs, J. A. (1996). "Gender Inequality and Higher Education". Annual Review of Sociology. 22: 153–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.153.

- ↑ "College gender gap widens: 57% are women". USA Today. 19 October 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Bidwell, Allie (2014-10-31). "Women More Likely to Graduate College, but Still Earn Less Than Men". US News & World Report. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ↑ Solmon, Melinda A., Lee, Amelia M. (Jan 200). "Research on Social Issues in Elementary School Physical Education". Elementary School Journal. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Cooper, Brenda (2002-03-01). "Boys Don't Cry and female masculinity: reclaiming a life & dismantling the politics of normative heterosexuality". Critical Studies in Media Communication. 19 (1): 44–63. doi:10.1080/07393180216552. ISSN 1529-5036.

- ↑ Cassese, Erin C.; Bos, Angela L.; Schneider, Monica C. (2014-07-01). "Whose American Government? A Quantitative Analysis of Gender and Authorship in American Politics Texts". Journal of Political Science Education. 10 (3): 253–272. doi:10.1080/15512169.2014.921655. ISSN 1551-2169.

- ↑ Droulet, D. (2007, September) Minding the Gender Gap. Retrieved from University Affairs website: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- 1 2 Taylor, Donna Lester (2004). ""Not just boring stories": Reconsidering the gender gap for boys". Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 48 (4): 290–298. doi:10.1598/JAAL.48.4.2.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011. , additional text.

- ↑ Booth D., Bruce F., Elliott-Johns S. (February 2009) Boys' Literacy Attainment: Research and related practice. Report for the 2009 Ontario Education Research Symposium. Centre for Literacy at Nipissing University. Retrieved from Ontario Ministry of Education website: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/research/boys_literacy.pdf

- ↑ Martino W. (April 2008) Underachievement: Which Boys are we talking about? What Works? Research into Practice. The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat. Retrieved from Ontario Ministry of Education website: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Martino.pdf

- 1 2 3 Smith, Michael W.; Jeffrey D. Wilhelm (2002). "Reading don't fix no Chevys" : literacy in the lives of young men. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann. ISBN 0867095091.

- ↑ Tapscott, D. (2009) Grown Up Digital. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ "Boy's Own Story", Reporter: Susan Ormiston, Producer: Marijka Hurko, 25 November 2003.

- ↑ Pahlke, Erin; Hyde, Janet Shibley; Allison, Carlie M. (2014-07-01). "The effects of single-sex compared with coeducational schooling on students' performance and attitudes: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (4): 1042–1072. doi:10.1037/a0035740. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 24491022.

- ↑ "New Study Shows Homeschoolers Excel Academically". Home School Legal Defense Association. 10 August 2009.

- 1 2 Voyeur, Daniel (2014). "Gender Differences in Scholastic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 140: 1174–1204. doi:10.1037/a0036620. PMID 24773502.

- 1 2 3 Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (2015-01-01). "Sex differences in academic achievement are not related to political, economic, or social equality". Intelligence. 48: 137–151. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2014.11.006.

References

- Clarricoates, Katherine (1978). 'Dinosaurs in the Classroom'-- A Re-examination of Some Aspects of the 'Hidden' Curriculum in Primary Schools.

- Rodgers, Jenny (2014). Aspirational Practice: Gender Equality The challenge of gender and heterosexual stereotypes in primary Education.