Sex differences in psychology

| This article is one of a series on: |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

| Physiology |

| Medicine |

| Neuroscience |

| Sociology |

Sex differences in psychology are differences in the mental functions and behaviors of the sexes, and are due to a complex interplay of biological, developmental, and cultural factors. Differences have been found in a variety of fields such as mental health, cognitive abilities, personality, and tendency towards aggression. Such variation may be both innate or learned and is often very difficult to distinguish. Modern research attempts to distinguish between such differences, and to analyze any ethical concerns raised. Since behavior is a result of interactions between nature and nurture researchers are interested in investigating how biology and environment interact to produce such differences,[1][2][3] although this is often not possible.[4]

A number of factors combine to influence the development of sex differences, including genetics and epigenetics;[5] differences in brain structure and function;[6] hormones;[7] or differences in psychological traits such as emotion, motivation, cognition, and sexuality.[8][9][10][11][12] Differences in socialization of males and females may decrease or increase the size of sex differences.[1][2][11]

History

Beliefs about sex differences have likely existed throughout history.[13] In his 1859 book On the Origin of Species Charles Darwin proposed that, like physical traits, psychological traits evolve through the process of sexual selection:

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.

— Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, 1859, p. 449.

Two of his later books, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) explore the subject of psychological differences between the sexes. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex includes 70 pages on sexual selection in human evolution, some of which concerns psychological traits.[14]

Psychological traits

Development of gender identity

Individuals who are sex reassigned at birth offer an opportunity to see what happens when a child who is genetically one sex is raised as the other. An infamous sexual reassignment case was that of David Reimer. Reimer was born biologically as a male but was raised as a female following medical advice after an operation that destroyed his genitalia. The reassignment was considered to be an especially valid test of the social learning concept of gender identity for several of the unique circumstances of the case. Despite the hormone therapies and surgeries, Reimer failed to identify as a female. According to his and his parents' accounts, the gender reassignment has caused severe mental problems throughout his life. At the age of 38, Reimer committed suicide.[15][16][17]

Some individuals hold a different gender identity than that assigned at birth according to their sex, and are referred to as transgender. These cases often involve significant gender dysphoria similar to the experience of David Reimer. How these identities are formed is unknown, although some studies have suggested that male-to-female transgenderism is related to androgen levels during fetal development.[18]

Childhood play

Many different studies have been conducted on sex differences in the play behavior of young children, often yielding conflicting results. One study conducted on nineteen-month-old children revealed a male preference for stereotypically "masculine" toys, and a female preference for stereotypically "feminine" toys, with males showing more variance in play behavior.[19] A study of thirteen-month-old children supported the theory that males and females typically prefer toys typed to their gender, but instead found females showing more variance instead of males.[20] An additional study found that a gendered divide in regards to toys may express itself as early as nine-months of age.[21] Despite these apparent differences, a study of toddlers showed that both boys and girls were equally active when playing, and both sexes preferred toys that allowed them to express this.[22]

The specific cause of this sex difference has also been investigated. A study with 112 boys and 100 girls found that the difference in play behavior appeared to be semi-correlated with fetal testosterone.[23] Girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia and thus exposed to high androgen levels during pregnancy tend to play more with male-typical toys and less with female-typical ones.[24][25] However, some have argued that the characteristics of the condition itself could also result in those girls preferring different types of toys.[26][27]

One study also claimed that one-day-old girls gaze longer at a face, whereas suspended mechanical mobiles, rather than a face, keep boys' attention for longer, though this study has been criticized as having methodological flaws.[28] Research has shown that when male-typical toys are labeled as female-appropriate, young girls become significantly more likely to play with them.[29] Certain studies have concluded that many end up treating infants and toddlers differently based on their assumed gender, even if boys and girls express the same behavior.[30][31][32] Children raised by lesbian mothers were reported by the parents to be more androgynous in personality, suggesting that, if the reporting is accurate, upbringing could influence certain gendered traits.[33]

Human-like play preferences have also been observed in guenon[34] and rhesus macaques,[35] though the co-author of the latter study warned about over-interpreting the data.[36]

Sexual behavior

Psychological theories exist regarding the development and expression of gender differences in human sexuality. A number of these theories are consistent in predicting that men should be more approving of casual sex (sex happening outside a stable, committed relationship such as marriage) and should also be more promiscuous (have a higher number of sexual partners) than women:[37]

Neoanalytic theories are based on the observation that mothers, as opposed to fathers, bear the major responsibility for childcare in most families and cultures; both male and female infants therefore form an intense emotional attachment to their mother, a woman. According to feminist psychoanalytic theorist Nancy Chodorow, girls tend to preserve this attachment throughout life and define their identities in relational terms, whereas boys must reject this maternal attachment in order to develop a masculine identity. In addition, this theory predicts that women's economic dependence on men in a male-dominated society will tend to cause women to approve of sex more in committed relationships providing economic security, and less so in casual relationships.[37]

A sociobiological approach applies evolutionary biology to human sexuality, emphasizing reproductive success in shaping patterns of sexual behavior. According to sociobiologists, since women's parental investment in reproduction is greater than men's, owing to human sperm being much more plentiful than eggs, and the fact that women must devote considerable energy to gestating their offspring, women will tend to be much more selective in their choice of mates than men. It may not be possible to accurately test sociobiological theories in relation to promiscuity and casual sex in contemporary (U.S.) society, which is quite different from the ancestral human societies in which most natural selection for sexual traits has occurred.[37]

According to social learning theory, sexuality is influenced by people's social environment. This theory suggests that sexual attitudes and behaviors are learned through observation of role models such as parents and media figures, as well as through positive or negative reinforcements for behaviors that match or defy established gender roles. It predicts that gender differences in sexuality can change over time as a function of changing social norms, and also that a societal double standard in punishing women more severely than men (who may in fact be rewarded) for engaging in promiscuous or casual sex will lead to significant gender differences in attitudes and behaviors regarding sexuality.[37]

Such a societal double-standard also figures in social role theory, which suggests that sexual attitudes and behaviors are shaped by the roles that men and women are expected to fill in society, and script theory, which focuses on the symbolic meaning of behaviors; this theory suggests that social conventions influence the meaning of specific acts, such as male sexuality being tied more to individual pleasure and macho stereotypes (therefore predicting a high number of casual sexual encounters) and female sexuality being tied more to the quality of a committed relationship.[37]

The Sexual Strategies Theory by David Buss and David P. Schmitt is an evolutionary psychology theory regarding female and male short-term and long-term mating strategies which they argued are dependent on several different goals and vary depending on the environment.[38][39][40] Terri D. Conley et al. has argued that other empirical evidence support smaller or non-existing gender differences and social theories such as stigma, socialization, and double standards.[41]

Intelligence

With the advent of the concept of g, or general intelligence, some form of empirically measuring differences in intelligence, was possible, but results have been inconsistent. Studies have shown either no differences, or advantages for both sexes, with most showing a slight advantage for males.[42][43] One study did find some advantage for women in later life,[44] while another found that male advantages on some cognitive tests are minimized when controlling for socioeconomic factors.[45] The differences in average IQ between women and men are small in magnitude and inconsistent in direction,[24][46] although the variability of male scores has been found to be greater than that of females, resulting in more males than females in the top and bottom of the IQ distribution.[47]

According to the 1995 report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns by the American Psychological Association, "Most standard tests of intelligence have been constructed so that there are no overall score differences between females and males."[24] Arthur Jensen in 1998 conducted studies on sex differences in intelligence through tests that were "loaded heavily on g" but were not normed to eliminate sex differences. His conclusions he quoted were "No evidence was found for sex differences in the mean level of g. Males, on average, excel on some factors; females on others". Jensen’s results that no overall sex differences existed for g has been strengthened by researchers who assessed this issue with a battery of 42 mental ability tests and found no overall sex difference.[48]

Although most of the tests showed no difference, there were some that did. For example, they found females performed better on verbal abilities while males performed better on visuospatial abilities.[48] One female advantage is in verbal fluency where they have been found to perform better in vocabulary, reading comprehension, speech production and essay writing.[49] Males have been specifically found to perform better on spatial visualization, spatial perception, and mental rotation.[49] Researchers had then recommended that general models such as fluid and crystallized intelligence be divided into verbal, perceptual and visuospatial domains of g, because when this model is applied then females excel at verbal and perceptual tasks while males on visuospatial tasks.[48]

There are however also differences in the capacity of males and females in performing certain tasks, such as rotation of objects in space, often categorized as spatial ability. Other traditionally male advantages, such as in the field of mathematics are less clear.[28] Although females have lesser performance in spatial abilities, they have better performance in processing speed involving letters, digits and rapid naming tasks,[50] object location memory, verbal memory,[51] and also verbal learning.[52]

Memory

The results from research on sex differences in memory are mixed and inconsistent, with some studies showing no difference, and others showing a female or male advantage.[53] Most studies have found no sex differences in short term memory, the rate of memory decline due to aging, or memory of visual stimuli.[53] Females have been found to have an advantage in recalling auditory and olfactory stimuli, experiences, faces, names, and the location of objects in space.[53][54] However, males show an advantage in recalling "masculine" events.[53] A study examining sex differences in performance on the California Verbal Learning Test found that males performed better on Digit Span Backwards and on reaction time, while females were better on short-term memory recall and Symbol-Digit Modalities Test.[45] Females have also demonstrated to have better verbal memory.[51]

A study was conducted to explore regions within the brain that are activated during working memory tasks in males versus females. Four different tasks of increasing difficulty were given to 9 males and 8 females. Functional magnetic resonance imaging was used to measure brain activity. The lateral prefrontal cortices, the parietal cortices and caudates were activated in both genders.[55] With more difficult tasks, more brain tissue was activated. The left hemisphere was predominantly activated in females' brains, whereas there was bilateral activation in males' brains.[55]

Aggression

Although research on sex differences in aggression show that males are generally more likely to display aggression than females, how much of this is due to social factors and gender expectations is unclear. Aggression is closely linked with cultural definitions of "masculine" and "feminine". In some situations, women show equal or more aggression than men, although less physical; for example, women are more likely to use direct aggression in private, where other people cannot see them, and are more likely to use indirect aggression in public.[56] Men are more likely to be the targets of displays of aggression and provocation than females. Studies by Bettencourt and Miller show that when provocation is controlled for, sex differences in aggression are greatly reduced. They argue that this shows that gender-role norms play a large part in the differences in aggressive behavior between men and women.[57] Psychologist Anne Campbell argues that females are more likely to use indirect aggression, and that "cultural interpretations have 'enhanced' evolutionarily based sex differences by a process of imposition which stigmatises the expression of aggression by females and causes women to offer exculpatory (rather than justificatory) accounts of their own aggression".[58]

According to the 2015 International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, sex differences in aggression is one of the most robust and oldest findings in psychology.[59] Past meta-analyses in the encyclopedia found males regardless of age engaged in more physical and verbal aggression while small effect for females engaging in more indirect aggression such as rumor spreading or gossiping.[59] It also found males tend to engage in more unprovoked aggression at higher frequency than females.[59] This replicated another 2007 meta-analysis of 148 studies in the journal of Child Development which found greater male aggression in childhood and adolescence.[60] This analysis also conforms with the Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology which reviewed past analysis and found greater male use in verbal and physical aggression with the difference being greater in the physical type.[61] A meta-analysis of 122 studies published in the journal of Aggressive Behavior found males are more likely to cyber-bully than females.[62] Difference also showed that females reported more cyber bullying behaviour during mid-adolescence while males showed more cyber bullying behaviour at late adolescence.[62]

The relationship between testosterone and aggression is unclear, and a causal link has not been conclusively shown.[63] Some studies indicate that testosterone levels may be affected by environmental and social influences.[64] The relationship is difficult to study since the only reliable measure of brain testosterone is from a lumbar puncture which is not done for research purposes and many studies have instead used less reliable measures such as blood testosterone. In humans, males engage in crime and especially violent crime more than females. The involvement in crime usually rises in the early teens to mid teens which happen at the same time as testosterone levels rise. Most studies support a link between adult criminality and testosterone although the relationship is modest if examined separately for each sex. However, nearly all studies of juvenile delinquency and testosterone are not significant. Most studies have also found testosterone to be associated with behaviors or personality traits linked with criminality such as antisocial behavior and alcoholism.[65]

In species that have high levels of male physical competition and aggression over females, males tend to be larger and stronger than females. Humans have modest general body sexual dimorphism on characteristics such as height and body mass. However, this may understate the sexual dimorphism regarding characteristics related to aggression since females have large fat stores. The sex differences are greater for muscle mass and especially for upper body muscle mass. Men's skeleton, especially in the vulnerable face, is more robust. Another possible explanation, instead of intra-species aggression, for this sexual dimorphism may be that it is an adaption for a sexual division of labor with males doing the hunting. However, the hunting theory may have difficulty explaining differences regarding features such as stronger protective skeleton, beards (not helpful in hunting, but they increase the perceived size of the jaws and perceived dominance, which may be helpful in intra-species male competition), and greater male ability at interception (greater targeting ability can be explained by hunting).[66]

There are evolutionary theories regarding male aggression in specific areas such as sociobiological theories of rape and theories regarding the high degree of abuse against stepchildren (the Cinderella effect). Another evolutionary theory explaining gender differences in aggression is the male warrior hypothesis, which explains that males have psychologically evolved for intergroup aggression in order to gain access to mates, resources, territory and status.[67][68]

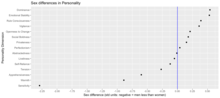

Personality traits

Cross-cultural research has shown gender differences on the tests measuring sociability and emotionality. For example, on the scales measured by the Big Five personality traits women consistently report higher Neuroticism, agreeableness, warmth (an extraversion facet[69]) and openness to feelings, and men often report higher assertiveness (a facet of extraversion[69]) and openness to ideas as assessed by the NEO-PI-R.[70] Gender differences in personality traits are largest in prosperous, healthy, and egalitarian cultures in which women have more opportunities that are equal to those of men. Differences in the magnitude of sex differences between more or less developed world regions were due to differences between men, not women, in these respective regions. That is, men in highly developed world regions were less neurotic, extroverted, conscientious and agreeable compared to men in less developed world regions. Women, on the other hand tended not to differ in personality traits across regions. Researchers have speculated that resource poor environments (that is, countries with low levels of development) may inhibit the development of gender differences, whereas resource rich environments facilitate them. This may be because males require more resources than females in order to reach their full developmental potential.[71] The authors argued that due to different evolutionary pressures, men may have evolved to be more risk-taking and socially dominant, whereas women evolved to be more cautious and nurturant. Hunter-gatherer societies in which humans originally evolved may have been more egalitarian than later agriculturally oriented societies. Hence, the development of gender inequalities may have acted to constrain the development of gender differences in personality that originally evolved in hunter-gatherer societies. As modern societies have become more egalitarian again it may be that innate sex differences are no longer constrained and hence manifest more fully than in less developed cultures. Currently, this hypothesis remains untested, as gender differences in modern societies have not been compared with those in hunter-gatherer societies.[71]

A personality trait directly linked to emotion and empathy where gender differences exist (see below) is Machiavellianism. Individuals who score high on this dimension are emotionally cool; this allows them to detach from others as well as values, and act egoistically rather than driven by affect, empathy or morality. In large samples of US college students males are on average more Machiavellian than females; in particular, males are over-represented among very high Machiavellians, while females are overrepresented among low Machiavellians.[73][74] A 2014 meta-analysis by researchers Rebecca Friesdorf and Paul Conway found that men score significantly higher on narcissism than women and this finding is robust across past literature.[75] The meta-analysis included 355 studies measuring narcissism across participants from the US, Germany, China, Netherlands, Italy, UK, Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Australia and Belgium as well as measuring latent factors from 124 additional studies.[75] The researchers noted that gender differences in narcissism is not just a measurement artifact but also represents true differences in the latent personality traits such as men’s heightened sense of entitlement and authority.[75]

Meta-analytic studies have also found males on average to be more assertive and having higher self-esteem. Females were on average higher than males in extraversion, anxiety, trust, and, especially, tender-mindedness (e.g., nurturance).[76] Women have also been found to be more punishment sensitive and men higher in sensation seeking and behavioural risk-taking. Deficits in effortful control also showed a very modest effect size in the male direction.[77]

A meta-analysis of scientific studies concluded that men prefer working with things and women prefer working with people. When interests were classified by RIASEC type Holland Codes (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, Conventional), Men showed stronger Realistic and Investigative interests, and women showed stronger Artistic, Social, and Conventional interests. Sex differences favoring men were also found for more specific measures of engineering, science, and mathematics interests.[78]

Empathy

Current literature find that women demonstrate more empathy across studies.[79] Women perform better than men in tests involving emotional interpretation, such as understanding facial expressions, and empathy.[80][81][82][83][84]

Some studies argue that this is related to the subject's perceived gender identity and gender expectations.[28] Additionally, culture impacts gender differences in the expression of emotions. This may be explained by the different social roles women and men have in different cultures, and by the status and power men and women hold in different societies, as well as the different cultural values various societies hold.[85] Some studies have found no differences in empathy between women and men, and suggest that perceived gender differences are the result of motivational differences.[86][87] Some researchers argue that because differences in empathy disappear on tests where it is not clear that empathy is being studied, men and women do not differ in ability, but instead in how empathetic they would like to appear to themselves and others.[28][88]

A review published in the journal Neuropsychologia found that women are better at recognizing facial effects, expression processing and emotions in general.[89] Men were only better at recognizing specific behaviour which includes anger, aggression and threatening cues.[89] A 2006 meta-analysis by researcher Rena A Kirkland from the North American Journal of Psychology found significant sex differences favouring females in "Reading of the mind" test. "Reading of the mind" test is an ability measure of theory of mind or cognitive empathy in which Kirkland's analysis involved 259 studies across 10 countries.[90] Another 2014 meta-analysis in the journal of Cognition and Emotion, found overall female advantage in non-verbal emotional recognition across 215 samples.[91]

An analysis from the journal of Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews found that there are sex differences in empathy from birth which remains consistent and stable across lifespan.[79] Females were found to have higher empathy than males while children with higher empathy regardless of gender continue to be higher in empathy throughout development.[79] Further analysis of brain tools such as event related potentials found that females who saw human suffering had higher ERP waveforms than males .[79] Another investigation with similar brain tools such as N400 amplitudes found higher N400 in females in response to social situations which positively correlated with self-reported empathy.[79] Structural fMRI studies found females have larger grey matter volumes in posterior inferior frontal and anterior inferior parietal cortex areas which are correlated with mirror neurons in fMRI literature.[79] Females were also found to have stronger link between emotional and cognitive empathy.[79] The researchers found that the stability of these sex differences in development are unlikely to be explained by any environment influences but rather might have some roots in human evolution and inheritance.[79]

An evolutionary explanation for the difference is that understanding and tracking relationships and reading others' emotional states was particularly important for women in prehistoric societies for tasks such as caring for children and social networking.[92] Throughout prehistory, females nurtured and were the primary caretakers of children so this might have led to an evolved neurological adaptation for women to be more aware and responsive to non-verbal expressions. According to the Primary Caretaker Hypothesis, prehistoric males did not have same selective pressure as primary caretakers so therefore this might explain modern day sex differences in emotion recognition and empathy. .[93]

Emotion

When measured with an affect intensity measure, women reported greater intensity of both positive and negative affect than men. Women also reported a more intense and more frequent experience of affect, joy, and love but also experienced more embarrassment, guilt, shame, sadness, anger, fear, and distress. Experiencing pride was more frequent and intense for men than for women.[85] In imagined frightening situations, such as being home alone and witnessing a stranger walking towards your house, women reported greater fear. Women also reported more fear in situations that involved "a male's hostile and aggressive behavior" (281)[85] In anger-eliciting situations, women communicated more intense feelings of anger than men. Women also reported more intense feelings of anger in relation to terrifying situations, especially situations involving a male protagonist.[94] Emotional contagion refers to the phenomenon of a person's emotions becoming similar to those of surrounding people. Women have been reported to be more responsive to this.[95]

Women are stereotypically more emotional and men are stereotypically angrier.[85][96] When lacking substantial emotion information they can base judgments on, people tend to rely more on gender stereotypes. Results from a study conducted by Robinson and colleagues implied that gender stereotypes are more influential when judging others' emotions in a hypothetical situation.[97]

There are documented differences in socialization that could contribute to sex differences in emotion and to differences in patterns of brain activity. An American Psychological Association article states that, "boys are generally expected to suppress emotions and to express anger through violence, rather than constructively". A child development researcher at Harvard University argues that boys are taught to shut down their feelings, such as empathy, sympathy and other key components of what is deemed to be pro-social behavior. According to this view, differences in emotionality between the sexes are theoretically only socially-constructed, rather than biological.[98]

Context also determines a man or woman's emotional behavior. Context-based emotion norms, such as feeling rules or display rules, "prescribe emotional experience and expressions in specific situations like a wedding or a funeral", independent of the person's gender. In situations like a wedding or a funeral, the activated emotion norms apply to and constrain every person in the situation. Gender differences are more pronounced when situational demands are very small or non-existent as well as in ambiguous situations. During these situations, gender norms "are the default option that prescribes emotional behavior" (290-1).[85]

Scientists in the field distinguish between emotionality and the expression of emotion: Associate Professor of Psychology Ann Kring said, "It is incorrect to make a blanket statement that women are more emotional than men, it is correct to say that women show their emotions more than men." In two studies by Kring, women were found to be more facially expressive than men when it came to both positive and negative emotions. These researchers concluded that women and men experience the same amount of emotion, but that women are more likely to express their emotions.[99]

Women are known to have anatomically differently shaped tear glands than men as well as having more of the hormone prolactin, which is present in tear glands, as adults. While girls and boys cry at roughly the same amount at age 12, by age 18, women generally cry four times more than men, which could be explained by higher levels of prolactin.[100]

Women show a significantly greater activity in the left amygdala when encoding and remembering emotionally disturbing pictures (such as mutilated bodies[101]). Men and women tend to use different neural pathways to encode stimuli into memory. While highly emotional pictures were remembered best by all participants in one study, as compared to emotionally neutral images, women remembered the pictures better than men. This study also found greater activation of the right amygdala in men and the left amygdala in women.[102] On average, women use more of the left cerebral hemisphere when shown emotionally arousing images, while men use more of their right hemisphere. Women also show more consistency between individuals for the areas of the brain activated by emotionally disturbing images.[101]

A 2003 worldwide survey by the Pew Research Center found that overall women stated that they were somewhat happier than men with their lives. Compared to the previous report five years earlier women more often reported progress with their lives while men were more optimistic about the future. Women were more concerned about home and family issues than men who were more concerned about issues outside the home. Men were happier than women regarding the family life and more optimistic regarding the children's future.[103]

Ethics and moral orientation

Meta-analysis on sex differences of moral orientation have found that women tend towards a more care based morality while men tend towards a more justice based morality.[104] This is usually based on the fact that men have a more slight utilitarian reasoning while women have more deontological reasoning which is largely because of greater female affective response and rejection of harm-based behaviours.[105] A meta-analysis published in the 2013 journal of Ethics and Behaviour after reviewing 19 primary studies also found women have greater moral sensitivity than men.[106]

Mental health

Childhood conduct disorder and adult antisocial personality disorder as well as substance use disorders are more common in men. Many mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders are more common in women. One explanation is that men tend to externalize stress while women tend to internalize it. Gender differences vary to some degree for different cultures.[107] Women are more likely than men to show unipolar depression. One 1987 study found little empirical support for several proposed explanations, including biological ones, and argued that when depressed women tend to ruminate which may lower the mood further while men tend to distract themselves with activities. This may develop from women and men being raised differently.[108]

Men and women do not differ on their overall rates of psychopathology; however, certain disorders are more prevalent in women, and vice versa. Women have higher rates of anxiety and depression (internalizing disorders) and men have higher rates of substance abuse and antisocial disorders (externalizing disorders). It is believed that divisions of power and the responsibilities set upon each sex are critical to this predisposition. Namely, women earn less money than men do, they tend to have jobs with less power and autonomy, and women are more responsive to problems of people in their social networks. These three differences can contribute to women's predisposition to anxiety and depression. It is believed that socializing practices that encourage high self-regard and mastery would benefit the mental health of both women and men.[109]

One study interviewed 18,572 respondents, aged 18 and over, about 15 phobic symptoms. These symptoms would yield diagnoses based on criteria for agoraphobia, social phobia, and simple phobia. Women had significantly higher prevalence rates of agoraphobia and simple phobia; however, there were no differences found between men and women in social phobia. The most common phobias for both women and men involved spiders, bugs, mice, snakes, and heights. The biggest differences between men and women in these disorders were found on the agoraphobic symptoms of "going out of the house alone" and "being alone", and on two simple phobic symptoms, involving the fear of "any harmless or dangerous animal" and "storms", with relatively more women having both phobias. There were no differences in the age of onset, reporting a fear on the phobic level, telling a doctor about symptoms, or the recall of past symptoms.[110]

One study interviewed 2,181 people in Detroit, aged 18–45, seeking to explain gender differences in exposure to traumatic events and in the development or emergence of post traumatic stress disorder following this exposure. It was found that lifetime prevalence of traumatic events was a little higher in men than in women. However, following exposure to a traumatic event, the risk for PTSD was two times higher in women. It is believed this difference is due to the greater risk women have of developing PTSD after a traumatic event that involved assaultive violence. In fact, the probability of a woman developing PTSD following assaultive violence was 36% compared to 6% of men. The duration of PTSD is longer in women, as well.[111]

Women and men are both equally likely at developing symptoms of schizophrenia, but the onset occurs earlier for men. It has been suggested that sexually dimorphic brain anatomy, the differential effects of estrogens and androgens, and the heavy exposure of male adolescents to alcohol and other toxic substances can lead to this earlier onset in men. It is believed that estrogens have a protective effect against the symptoms of schizophrenia. Although, it has been shown that other factors can contribute to the delayed onset and symptoms in women, estrogens have a large effect, as can be seen during a pregnancy. In pregnancy, estrogen levels are rising in women, so women who have had recurrent acute episodes of schizophrenia did not usually break down. However, after pregnancy, when estrogen levels have dropped, women tend to suffer from postpartum psychoses. Also, psychotic symptoms are exacerbated when, during the menstrual cycle, estrogen levels are at their lowest. In addition, estrogen treatment has yielded beneficial effects in patients with schizophrenia.[112]

Pathological gambling has been known to have a higher prevalence rate, 2:1, in men to women. One study chose to identify gender-related differences by examining male and female gamblers, who were using a gambling helpline. There was 562 calls placed, and of this amount, 62.1% were men, and 37.9% were women. Male gamblers were more likely to report problems with strategic forms of gambling (blackjack or poker), and female gamblers were more likely to report problems with nonstrategic forms, such as slots or bingo. Male gamblers were also more likely to report a longer duration of gambling than women. Female gamblers were more likely to report receiving mental health treatment that was not related to gambling. Male gamblers were more likely to report a drug problem or being arrested on account of gambling. There were high rates of debt and psychiatric symptoms related to gambling observed in both groups of men and women.[113]

There are also differences regarding gender and suicide. Males in Western societies are much more likely to die from suicide despite females having more suicide attempts.

The "extreme male brain theory" views autism as an extreme version of male-female differences regarding "systemizing" and empathizing abilities.[114] The "imprinted brain theory" argues that autism and psychosis are contrasting disorders on a number of different variables and that this is caused by an unbalanced genomic imprinting favoring paternal genes (autism) or maternal genes (psychosis).[115][116]

Cognitive control of behavior

Females tend to have a greater basal capacity to exert inhibitory control over undesired or habitual behaviors than males and respond differently to modulatory environmental contextual factors.[117] For example, listening to music tends to significantly improve the rate of response inhibition in females, but reduce the rate of response inhibition in males.[117] A 2010 meta-analyses found that women have small, but persistent, advantages in punishment sensitivity and effortful control across cultures.[118] A 2014 review found that In humans, women discount more steeply than men, but sex differences on measures of impulsive action depend on tasks and subject samples.[119]

Possible causes

Biology

Genetics

Psychological traits can vary between the sexes through sex-linkage. That is to say, what causes a trait may be related to the chromosomal sex of the individual.[120] In contrast, there are also[121] "sex-influenced" (or sex-conditioned) traits, in which the phenotypic manifestation of a gene depends on the sex of the individual.[122] Even in a homozygous dominant or recessive female the condition may not be expressed fully. "Sex-limited" traits are characteristics only expressed in one sex. They may be caused by genes on either autosomal or sex chromosomes.[122]

Evidence exists that there are sex-linked differences between the male and female brain.[123] Epigenetic changes have also been found to cause sex-based differentiation in the brain.[124] The extent and nature of these differences are not fully characterised.[28][123][124]

Brain structure and function

When it comes to the brain there are many similarities but also a number of differences in structure, neurotransmitters, and function.[125][126] However, some argue that innate differences in the neurobiology of women and men have not been conclusively identified.[28][127]

Structurally adult male brains are on average 11–12% heavier and 10% bigger than female brains.[128][129] Despite this, because of relative difference in body size the brain-to-body mass ratio does not differ between the sexes.[130][131]Other studies have stated bigger male brain size can only be partly accounted by body size.[132] Researchers also found greater cortical thickness and cortical complexity in females and greater female cortical surface area after adjusting for brain volumes.[132] Given that cortical complexity and cortical features are positively correlated with intelligence, researchers postulated that these differences might have evolved for females to compensate for smaller brain size and equalize overall cognitive abilities with males.[132] Women have a greater developed neuropil or the space between neurons, which contains synapses, dendrites and axons[129] and the cortex has neurons packed more closely together in the temporal and prefrontal cortex.[129] Females also have greater cortical thickness in posterior temporal and inferior parietal regions compared to males independent of differences in brain or body size.[129]

Though statistically there are sex differences in white matter and gray matter percentage, this ratio is directly related to brain size, and some argue these sex differences in gray and white matter percentage are caused by the average size difference between men and women.[133][134][135][136] Others argue that these differences remain after controlling for brain volume.[126]

In a 2013 meta-analysis, researchers found on average males had larger grey matter volume in bilateral amygdalae, hippocampi, anterior parahippocampal gyri, posterior cingulate gyri, precuneus, putamen and temporal poles, areas in the left posterior and anterior cingulate gyri, and areas in the cerebellum bilateral VIIb, VIIIa and Crus I lobes, left VI and right Crus II lobes.[137] On the other hand, females on average had larger grey matter volume at the right frontal pole, inferior and middle frontal gyri, pars triangularis, planum temporale/parietal operculum, anterior cingulate gyrus, insular cortex, and Heschl's gyrus; bilateral thalami and precuneus; the left parahippocampal gyrus and lateral occipital cortex (superior division).[137] The meta-analysis found larger volumes in females were most pronounced in areas in the right hemisphere related to language in addition to several limbic structures such as the right insular cortex and anterior cingulate gyrus.[137]

Amber Ruigrok's 2013 meta-analysis also found greater grey matter density in the average male left amygdala, hippocampus, insula, pallidum, putamen, claustrum and right cerebellum.[137] The meta-analysis also found greater grey matter density in the average female left frontal pole.[137]

According to the neuroscience journal review series Progress in Brain Research, it has been found that males have larger and longer planum temporale and Sylvian fissure while females have significantly larger proportionate volumes to total brain volume in the superior temporal cortex, Broca's area, the hippocampus and the caudate.[132] The midsagittal & fiber numbers in the anterior commissure that connect the temporal poles and mass intermedia that connects the thalami is also larger in women.[132]

In the cerebral cortex, it has been observed that there is greater intra-lobe neural communication in male brains and greater inter-lobe (between the left and right hemispheres of the cerebral cortex) neural communication in female brains. In the cerebellum, the region of the brain that plays an important role in motor functions, males showed higher connectivity between hemispheres, and females showed higher connectivity within hemispheres. This potentially provides a neural basis for previous studies that showed sex-specific difference in certain psychological functions. Females on average outperform males on emotional recognition and nonverbal reasoning tests, while males outperform females on motor and spatial cognitive tests.[138][139][140][141]

In the work of[142] Szalkai et al. have computed structural (i.e., anatomical) connectomes of 96 subjects of the Human Connectome Project, and they have shown that in several deep graph-theoretical parameters, the structural connectome of women is significantly better connected than that of men. For example, women's connectome has more edges, higher minimum bipartition width, larger eigengap, greater minimum vertex cover than that of men. The minimum bipartition width (or the minimum balanced cut (see Cut (graph theory))) is a well-known measure of quality of computer multistage interconnection networks, it describes the possible bottlenecks in network communication: the higher this value is, the better is the network. The larger eigengap shows that the female connectome is a better expander graph than the connectome of males. The better expanding property, the higher minimum bipartition width and the greater minimum vertex cover show deep advantages in network connectivity in the case of female braingraph. Szalkai et al.[143] have also shown that most of the deep graph theoretical differences remain in effect if big-brained women and small-brained men are compared: i.e., the graph theoretical differences are due to sex, and not the brain volume-differences of the subjects.

Hormones

Testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation in male primates, including humans. The elimination of testosterone in adulthood has been shown to reduce sexual motivation in both male humans and male primates.[144] Male humans who had their testicular function suppressed with a GnRH anatagonist displayed decreases in sexual desire and masturbation two weeks following the procedure.[145] It is also suggested that levels of testosterone in men are related to the type of relationship in which they are involved. Men involved in polyamorous relationships display higher levels of testosterone than men involved in either a single partner relationship or single men.[146]

Research on the ovulatory shift hypothesis explores differences in female mate preferences across the ovulatory cycle. Non-pill using heterosexual females who are ovulating (high levels of estrogens) were shown to have a preference for the scent of males with low levels of fluctuating asymmetry.[147] Certain research has also indicated that ovulating heterosexual females display a preference toward masculine faces and report greater sexual attraction to males other than their current partner,[148] though this has been called into question. A meta-analysis of 58 studies concluded that there was no evidence to support this theory.[149] A different meta-analysis partially supported the hypothesis, but only in regards to "short-term" attractiveness.[150] A later study of Finnish twins found that the influence of "context-dependent" factors (such as ovulation) on a female's attraction to masculine faces was less than one-percent.[151] Additionally, a 2016 paper suggested that any possible changes in preferences during ovulation would be moderated by the relationship quality itself, even to the point of inversion in favor of the female's current partner.[152]

Culture

Fundamental sex differences in genetics, hormones and brain structure and function may manifest as distal cultural phenomena (e.g., males as primary combatants in warfare, the primarily female readership of romance novels, etc.).[8][153] In addition, differences in socialization of males and females may have the effect of decreasing or increasing the magnitude of sex differences.[1][2]

Controversy

In January 2005, Lawrence Summers, president of Harvard University, unintentionally provoked a public controversy when several attendees discussed with reporters some statements he made during his lunchtime presentation at an economics conference at the National Bureau of Economic Research.[154][155][156] In analyzing the disproportionate numbers of men over women in high-end science and engineering jobs he suggested that part of discrepancy may be due in part to the conflict between employers' demands for high time commitments and women's disproportionate role in the raising of children. He also suggested that well documented greater variability among men (in comparison to women) on tests of cognitive abilities[157][158][159] may be due to intrinsic factors,[154] adding that he "would like nothing better than to be proved wrong". The controversy generated a great deal of media attention; it contributed to the resignation of Summers the following year,[160] and led Harvard to commit $50 million to the recruitment and hiring of women faculty.[161] Stimulated by this controversy, in May 2005, Harvard University psychology professors Steven Pinker and Elizabeth Spelke debated "The Science of Gender and Science".[162]

In 2006, Danish psychologist and intelligence researcher Helmuth Nyborg was temporarily suspended from his position at Aarhus University, after being accused of scientific misconduct in relation to the documentation of a peer-reviewed paper appearing in the journal Personality and Individual Differences, in which he showed a 3.15-point IQ advantage of men over women.[43] This led to a review of his work by an investigative committee. Nyborg was defended — and the university criticized — by other researchers in the intelligence field.[100][163][164]

In July 2012, IQ researcher Jim Flynn was widely misquoted in the media as claiming that women had surpassed men on IQ tests for the first time in a century.[165] In a 2012 lecture, Flynn responded by denouncing the media reports as distortions, and made it clear that his data instead showed a rough parity between the sexes in a few countries on the Raven's Matrices for boys and girls between the ages of 14 and 18. Women, he argued, had previously scored lower than men on the Raven's tests, but reached equality with men in these nations as a result of exposure to modernity by entering the professions and being allowed greater educational access. Flynn stated that the minute variations that did appear were statistically negligible and were not attributable to differences in cognitive ability.[165][166]

Definition

Psychological sex differences refer to emotional, motivational or cognitive differences between the sexes.[167][168] Examples include a greater male tendencies toward violence,[169] or the belief that female brain is hardwired for empathy.[170]

The terms "sex differences" and "gender differences" are at times used interchangeably, sometimes to refer to differences in male and female behaviors as either biological ("sex differences") or environmental/cultural ("gender differences").[171] This distinction is difficult to make owing to failures of parsing one from the other.[171]

References

- 1 2 3 Lippa, R. A. (2009). Gender, Nature, and Nurture. NY: LEA.

- 1 2 3 Halpern, D. F. (2011). Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities (4th Edition). NY: Psychology Press

- ↑ Fausto-Sterling, A., (2012). Sex/Gender: Biology in a Social World. NY: Routledge.

- ↑ Halpern, Diane F. (2011). Sex differences in cognitive abilities (4 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 9781848729414. .

- ↑ Richardson, S. S. (2013) Sex Itself: The Search for Male and Female in the Human Genome Hardcover. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- ↑ Becker, J.B., Berkley, K. J., Geary, N., & Hampson, E. (2007) Sex Differences in the Brain: From Genes to Behavior by NY: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Helmuth, N. (1994). Hormones, Sex, and Society. NY: Praeger.

- 1 2 Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Wilson, M. & Daly, M. (1983) Sex, evolution and behavior.

- ↑ Low, B. (2000). Why sex matters. NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 1 2 Geary, D. C. (2009) Male, Female: The Evolution of Human Sex Differences. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association

- ↑ Gray, P. B. (2013). Evolution and Human Sexual Behavior. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Halpern, D. (2012). Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities (4th Ed.). NY: Psychology Press. p. 2.

- ↑ Miller, Geoffrey (2000). The Mating Mind. Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc. (First Anchor Books Edition, April 2001). New York, NY. Anchor ISBN 038549517X

- ↑ Colapinto, John (2006-08-08). As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0061120565.

- ↑ "Dr. Money And The Boy With No Penis". BBC Science & Nature - Horizon. BBC. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ Diamond, Milton; Sigmundson, HK (March 1997). "Sex reassignment at birth. Long-term review and clinical implications". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 151 (3): 298–304. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400084015. PMID 9080940. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ SCHNEIDER, H; PICKEL, J; STALLA, G. "Typical female 2nd–4th finger length (2D:4D) ratios in male-to-female transsexuals—possible implications for prenatal androgen exposure". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31 (2): 265–269. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.07.005.

- ↑ Alexander, Gerianne M.; Saenz, Janet (2012-09-01). "Early androgens, activity levels and toy choices of children in the second year of life". Hormones and Behavior. 62 (4): 500–504. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.08.008.

- ↑ Beek, Cornelieke van de; Goozen, Stephanie H. M. van; Buitelaar, Jan K.; Cohen-Kettenis, Peggy T. (2009-02-01). "Prenatal Sex Hormones (Maternal and Amniotic Fluid) and Gender-related Play Behavior in 13-month-old Infants". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 38 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9291-z. ISSN 0004-0002.

- ↑ Todd, Brenda K.; Barry, John A.; Thommessen, Sara A. O. (2017-05-01). "Preferences for 'Gender-typed' Toys in Boys and Girls Aged 9 to 32 Months". Infant and Child Development. 26 (3): n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/icd.1986. ISSN 1522-7219.

- ↑ O'brien, Marion; Huston, Aletha C. (1985-12-01). "Activity Level and Sex-Stereotyped Toy Choice in Toddler Boys and Girls". The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 146 (4): 527–533. doi:10.1080/00221325.1985.10532472. ISSN 0022-1325. PMID 3835231.

- ↑ Auyeung, B.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Ashwin, E.; Knickmeyer, R.; Taylor, K.; Hackett, G.; Hines, M. (2009). "Fetal testosterone predicts sexually differentiated childhood behavior in girls and in boys". Psychol. Sci. 20 (2): 144–148. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02279.x. PMC 2778233. PMID 19175758.

- 1 2 3 Neisser, Ulric; Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J., Jr.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert; et al. (1996). "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns". American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77.

- ↑ Berenbaum, Sheri A.; Hines, Melissa (1992). "Early Androgens Are Related to Childhood Sex-Typed Toy Preferences". Psychological Science. 3 (3): 203–6. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00028.x. JSTOR 40062786.

- ↑ "Biology doesn't justify gender divide for toys". New Scientist. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ↑ Jordan-Young, Rebecca M. (June 2012). "Hormones, context, and "brain gender": a review of evidence from congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Social Science & Medicine. 74 (11): 1738–1744. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.026. ISSN 1873-5347. PMID 21962724.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fine, Cordelia (2010). Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393068382.

- ↑ Weisgram, Erica S.; Fulcher, Megan; Dinella, Lisa M. (2014-09-01). "Pink gives girls permission: Exploring the roles of explicit gender labels and gender-typed colors on preschool children's toy preferences". Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 35 (5): 401–409. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.06.004.

- ↑ Clearfield, Melissa W.; Nelson, Naree M. (2006-01-01). "Sex Differences in Mothers' Speech and Play Behavior with 6-, 9-, and 14-Month-Old Infants". Sex Roles. 54 (1–2): 127–137. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-8874-1. ISSN 0360-0025.

- ↑ Donovan, Wilberta; Taylor, Nicole; Leavitt, Lewis. "Maternal self-efficacy, knowledge of infant development, sensory sensitivity, and maternal response during interaction". Developmental Psychology. 43 (4): 865–876. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.865.

- ↑ Mondschein, Emily R.; Adolph, Karen E.; Tamis-LeMonda, Catherine S. "Gender Bias in Mothers' Expectations about Infant Crawling". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 77 (4): 304–316. doi:10.1006/jecp.2000.2597.

- ↑ Goldberg, Abbie E.; Garcia, Randi L. (October 2016). "Gender-typed behavior over time in children with lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parents". Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43). 30 (7): 854–865. doi:10.1037/fam0000226. ISSN 1939-1293. PMC 5048516. PMID 27416364.

- ↑ Alexander, G.M.; Hines, M. (2002). "Sex differences in response to children's toys in nonhuman primates (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus)". Evolution & Human Behavior. 23 (6): 467–479. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(02)00107-1.

- ↑ Hassett, J.M.; Siebert, E.R.; Wallen, K. (2008). "Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children". Hormones and Behavior. 54 (3): 359–364. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.008. PMC 2583786. PMID 18452921.

- ↑ "Male monkeys prefer boys' toys". New Scientist. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oliver, Mary Beth; Hyde, Janet S. (2001). "Gender Differences in Sexuality: A Meta-Analysis". In Baumeister, Roy F. Social Psychology and Human Sexuality: Essential Readings. Psychology Press. pp. 29–43. ISBN 978-1-84-169019-3.

- ↑ Schuett, Wiebke; Tregenza, Tom; Dull, Sasha R. X. (2009-08-19). "Sexual selection and animal personality". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 217–246. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00101.x. PMID 19922534.

- ↑ Buss, David Michael; Schmitt, David P. (2011). "Evolutionary Psychology and Feminism". Sex Roles. 64 (9–10): 768–787. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9987-3.

- ↑ Petersen, JL; Hyde, JS (January 2010). "A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993-2007". Psychological Bulletin. 136 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1037/a0017504. PMID 20063924.

- ↑ Conley, T. D.; Moors, A. C.; Matsick, J. L.; Ziegler, A.; Valentine, B. A. (2011). "Women, Men, and the Bedroom: Methodological and Conceptual Insights That Narrow, Reframe, and Eliminate Gender Differences in Sexuality". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20 (5): 296–300. doi:10.1177/0963721411418467.

- ↑ Studies:

- Lynn, Richard (1999). "Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A developmental theory". Intelligence. 27: 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00009-4.

- Lynn, Richard; Irwing, Paul (2004). "Sex differences on the progressive matrices: A meta-analysis". Intelligence. 32 (5): 481–498. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.06.008.

- Irwing, Paul; Lynn, Richard (2005). "Sex differences in means on the progressive matrices in university students: A meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychology. 96 (4): 505–24. doi:10.1348/000712605X53542. PMID 16248939.

- Lynn, Richard (1994). "Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A paradox resolved". Personality and Individual Differences. 17 (2): 257–71. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90030-2.

- Blinkhorn, Steve (2005). "Intelligence: A gender bender". Nature. 438 (7064): 31–2. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...31B. doi:10.1038/438031a. PMID 16267535.

- Irwing, Paul; Lynn, Richard (2006). "Intelligence: Is there a sex difference in IQ scores?". Nature. 442 (7098): E1, discussion E1–2. Bibcode:2006Natur.442E...1I. doi:10.1038/nature04966. PMID 16823409.

- Jackson, Douglas N.; Rushton, J. Philippe (2006). "Males have greater g: Sex differences in general mental ability from 100,000 17- to 18-year-olds on the Scholastic Assessment Test". Intelligence. 34 (5): 479–486. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.03.005.

- 1 2 Nyborg, Helmuth (2005). "Sex-related differences in general intelligence g, brain size, and social status". Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (3): 497–509. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.011.

- ↑ Keith, Timothy Z.; Reynolds, Matthew R.; Patel, Puja G.; Ridley, Kristen P. (2008). "Sex differences in latent cognitive abilities ages 6 to 59: Evidence from the Woodcock–Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities". Intelligence. 36 (6): 502–25. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.11.001.

- 1 2 Jorm, Anthony F.; Anstey, Kaarin J.; Christensen, Helen; Rodgers, Bryan (2004). "Gender differences in cognitive abilities: The mediating role of health state and health habits". Intelligence. 32: 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.08.001.

- ↑ Studies:

- Baumeister, Roy F (2001). Social psychology and human sexuality: essential readings. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-019-3.

- Baumeister, Roy F. (2010). Is There Anything Good About Men?: How Cultures Flourish By Exploiting Men. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537410-0.

- Hedges, L.; Nowell, A (1995). "Sex differences in mental test scores, variability, and numbers of high-scoring individuals". Science. 269 (5220): 41–5. Bibcode:1995Sci...269...41H. doi:10.1126/science.7604277. PMID 7604277.

- Colom, R; García, LF; Juan-Espinosa, M; Abad, FJ (2002). "Null sex differences in general intelligence: Evidence from the WAIS-III". The Spanish journal of psychology. 5 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1017/s1138741600005801. PMID 12025362.

- ↑ Deary, Ian J.; Irwing, Paul; Der, Geoff; Bates, Timothy C. (2007). "Brother–sister differences in the g factor in intelligence: Analysis of full, opposite-sex siblings from the NLSY1979". Intelligence. 35 (5): 451–6. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.003.

- 1 2 3 Nisbet, Richard E (2012). "Intelligence New Findings and Theoretical Developments" (PDF). American Psychologist. 67 (2): 130–159. doi:10.1037/a0026699. PMID 22233090.

- 1 2 (us), National Academy of Sciences; (us), National Academy of Engineering; Engineering, and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and (2006-01-01). "Women in Science and Mathematics".

- ↑ Roivainen, Eka (2011). "Gender differences in processing speed: A review of recent research". Learning and Individual Differences. 21 (2): 145–149. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.021.

- 1 2 Li, Rena (2014-09-01). "Why women see differently from the way men see? A review of sex differences in cognition and sports". Journal of Sport and Health Science. 3 (3): 155–162. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2014.03.012. PMC 4266559. PMID 25520851.

- ↑ Wallentin, Mikkel (2009-03-01). "Putative sex differences in verbal abilities and language cortex: A critical review". Brain and Language. 108 (3): 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2008.07.001. PMID 18722007.

- 1 2 3 4 Ellis, Lee, Sex differences: summarizing more than a century of scientific research, CRC Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8058-5959-4, ISBN 978-0-8058-5959-1

- ↑ Halpern, Diane F., Sex differences in cognitive abilities, Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8058-2792-7, ISBN 978-0-8058-2792-7

- 1 2 Speck, Oliver; Ernst, Thomas; Braun, Jochen; Koch, Christoph; Miller, Eric; Chang, Linda (2000). "Gender differences in the functional organization of the brain for working memory". NeuroReport. 11 (11): 2581–5. doi:10.1097/00001756-200008030-00046. PMID 10943726.

- ↑ Chrisler, Joan C; Donald R. McCreary. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. Springer, 2010. ISBN 9781441914644.

- ↑ Bettencourt, B. Ann; Miller, Norman (1996). "Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 119 (3): 422–47. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.422. PMID 8668747.

- ↑ Campbell, Anne (1999). "Staying alive: Evolution, culture, and women's intrasexual aggression". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 22 (2): 203–14. doi:10.1017/S0140525X99001818. PMID 11301523.

- 1 2 3 "Gender Differences in Personality and Social Behavior". ResearchGate. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25100-3. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ↑ Card, Noel A.; Stucky, Brian D.; Sawalani, Gita M.; Little, Todd D. (2008-10-01). "Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment". Child Development. 79 (5): 1185–1229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. ISSN 1467-8624. PMID 18826521.

- ↑ Campbell, Anne (2007), "Sex differences in aggression", in Barrett, Louise; Dunbar, Robin (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198568308.

- 1 2 Barlett, Christopher; Coyne, Sarah M. (2014-10-01). "A meta-analysis of sex differences in cyber-bullying behavior: the moderating role of age". Aggressive Behavior. 40 (5): 474–488. doi:10.1002/ab.21555. ISSN 1098-2337. PMID 25098968.

- ↑ Studies:

- Baron, Robert A., Deborah R. Richardson, Human Aggression: Perspectives in Social Psychology, Springer, 2004, ISBN 0-306-48434-X, 9780306484346

- Albert, D.J.; Walsh, M.L.; Jonik, R.H. (1993). "Aggression in humans: What is its biological foundation?". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 17 (4): 405–25. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80117-4. PMID 8309650.

- Coccaro, Emil F.; Beresford, Brendan; Minar, Philip; Kaskow, Jon; Geracioti, Thomas (2007). "CSF testosterone: Relationship to aggression, impulsivity, and venturesomeness in adult males with personality disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 41 (6): 488–92. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.04.009. PMID 16765987.

- Constantino, John N.; Grosz, Daniel; Saenger, Paul; Chandler, Donald W.; Nandi, Reena; Earls, Felton J. (1993). "Testosterone and Aggression in Children". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 32 (6): 1217–22. doi:10.1097/00004583-199311000-00015. PMID 8282667.

- ↑ Hillbrand, Marc, Nathaniel J. Pallone, The psychobiology of aggression: engines, measurement, control: Volume 21, Issues 3-4 of Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 1-56024-715-0, ISBN 978-1-56024-715-9

- ↑ Handbook of Crime Correlates; Lee Ellis, Kevin M. Beaver, John Wright; 2009; Academic Press

- ↑ Puts, David A. (2010). "Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans". Evolution and Human Behavior. 31 (3): 157–175. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.005.

- ↑ McDonald, Melissa M.; Navarrete, Carlos David; Vugt, Mark Van (2012-03-05). "Evolution and the psychology of intergroup conflict: the male warrior hypothesis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1589): 670–679. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0301. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3260849. PMID 22271783.

- ↑ Vugt, Mark van (2006). "Gender Differences in Cooperation and Competition:The Male-Warrior Hypothesis" (PDF). Psychological Science. 18 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01842.x. PMID 17362372.

- 1 2 Facets of the Big Five

- ↑ Costa, Paul, Jr.; Terracciano, Antonio; McCrae, Robert R. (2001). "Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (2): 322–31. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322. PMID 11519935.

- 1 2 Schmitt, David P.; Realo, Anu; Voracek, Martin; Allik, Jüri (2008). "Why can't a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (1): 168–82. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168. PMID 18179326.

- ↑ Giudice, Marco Del; Booth, Tom; Irwing, Paul (2012-01-04). "The Distance Between Mars and Venus: Measuring Global Sex Differences in Personality". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29265. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729265D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029265. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ Christie, R. & Geis, F. (1970) "Studies in Machiavellianism". NY: Academic Press.

- ↑ Gunnthorsdottir, Anna; McCabe, Kevin; Smith, Vernon (2002). "Using the Machiavellianism instrument to predict trustworthiness in a bargaining game". Journal of Economic Psychology. 23: 49–66. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(01)00067-8.

- 1 2 3 Grijalva, Emily; Newman, Daniel A.; Tay, Louis; Donnellan, M. Brent; Harms, P. D.; Robins, Richard W.; Yan, Taiyi (2015). "Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 141 (2): 261–310. doi:10.1037/a0038231. PMID 25546498.

- ↑ Feingold, A. (1994-11-01). "Gender differences in personality: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 116 (3): 429–456. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 7809307.

- ↑ Cross, Catharine P.; Copping, Lee T.; Campbell, Anne (2011-01-01). "Sex differences in impulsivity: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 137 (1): 97–130. doi:10.1037/a0021591. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 21219058.

- ↑ Su, Rong; Rounds, James; Armstrong, Patrick (2009). "Men and Things, Women and People: A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Interests". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (6): 859–884. doi:10.1037/a0017364. PMID 19883140.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Christov-Moore, Leonardo; Simpson, Elizabeth A.; Coudé, Gino; Grigaityte, Kristina; Iacoboni, Marco; Ferrari, Pier Francesco (2014). "Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 46: 604–627. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001. PMC 5110041. PMID 25236781.

- ↑ Hall, Judith A. (1978). "Gender effects in decoding nonverbal cues". Psychological Bulletin. 85 (4): 845–857. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.4.845.

- ↑ Judith A. Hall (1984): Nonverbal sex differences. Communication accuracy and expressive style. 207 pp. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Judith A. Hall, Jason D. Carter & Terrence G. Horgan (2000): Gender differences in nonverbal communication of emotion. Pp. 97 - 117 i A. H. Fischer (ed.): Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Agneta H. Fischer & Anthony S. R. Manstead (2000): The relation between gender and emotions in different cultures. Pp. 71 - 94 i A. H. Fischer (ed.): Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Koirikivi, Iivo (April 2014). "Measurement of affective empathy with Pictorial Empathy Test (PET)" (PDF). Digital Repository of the University of Helsinki. Department of Behavioral Sciences. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Niedenthal, P.M., Kruth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2006). Psychology and emotion. (Principles of Social Psychology series). ISBN 1-84169-402-9. New York: Psychology Press

- ↑ Ickes, W. (1997). Empathic accuracy. New York: The Guilford Press.

- ↑ Klein, K. J. K.; Hodges, S. D. (2001). "Gender Differences, Motivation, and Empathic Accuracy: When it Pays to Understand". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 27 (6): 720–730. doi:10.1177/0146167201276007.

- ↑ Schaffer, Amanda (July 2, 2008). "The Sex Difference Evangelists". Slate.

- 1 2 Kret, M. E.; De Gelder, B. (2012-06-01). "A review on sex differences in processing emotional signals". Neuropsychologia. 50 (7): 1211–1221. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis reveals adult female superiority in "Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test"". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- ↑ Thompson, Ashley E.; Voyer, Daniel (2014-10-03). "Sex differences in the ability to recognise non-verbal displays of emotion: A meta-analysis". Cognition and Emotion. 28 (7): 1164–1195. doi:10.1080/02699931.2013.875889. ISSN 0269-9931. PMID 24400860.

- ↑ Geary, David C. (1998). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. American Psychological Association. ISBN 1-55798-527-8.

- ↑ Christov-Moore, Leonardo (2014). "Empathy:Gendereffects in brain and behavior". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 46: 604–627. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001. PMC 5110041. PMID 25236781.

- ↑ Brody, Leslie R.; Lovas, Gretchen S.; Hay, Deborah H. (1995). "Gender differences in anger and fear as a function of situational context". Sex Roles. 32: 47–78. doi:10.1007/BF01544757.

- ↑ Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J.T., & Rapson, R.L. (1994) Emotional contagion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Wilson, Tracy V. "How Women Work" How Stuff Works. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael D.; Johnson, Joel T.; Shields, Stephanie A. (1998). "The Gender Heuristic and the Database: Factors Affecting the Perception of Gender-Related Differences in the Experience and Display of Emotions". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 20 (3): 206–219. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2003_3.

- ↑ Murray, Bridgett "Boys to Men: Emotional Miseducation". APA.

- ↑ Reeves, Jamie Lawson "Women more likely than men to but emotion into motion". Vanderbilt News. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- 1 2 Wood, Samual; Wood, Ellen; Boyd Denise (2004). "World of Psychology, The (Fifth Edition)", Allyn & Bacon ISBN 0-205-36137-4

- 1 2 Motluk, Alison. "Women's better emotional recall explained". NewScientist. July 22, 2002. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Canli, T.; Desmond, J. E.; Zhao, Z.; Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2002). "Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (16): 10789–10794. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910789C. doi:10.1073/pnas.162356599. PMC 125046. PMID 12145327.

- ↑ Global Gender Gaps: Women Like Their Lives Better, Pew Research Center October 29, 2003, http://www.pewglobal.org/2003/10/29/global-gender-gaps/

- ↑ Jaffee, Sara; Hyde, Janet Shibley (2000). "Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 126 (5): 703–726. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.703.

- ↑ Friesdorf, R.; Conway, P.; Gawronski, B. (2015). "Gender Differences in Responses to Moral Dilemmas: A Process Dissociation Analysis". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 41 (5): 696–713. doi:10.1177/0146167215575731. PMID 25840987.

- ↑ "Gender Differences in Moral Sensitivity: A Meta-Analysis | Ethics Education Library". ethics.iit.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-18.

- ↑ Afifi, M (2007). "Gender differences in mental health". Singapore medical journal. 48 (5): 385–91. PMID 17453094.

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (1987). "Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory". Psychological Bulletin. 101 (2): 259–82. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.259. PMID 3562707.

- ↑ Rosenfield, Sarah. "Gender and mental health: Do women have more psychopathology, men more, or both the same (and why)?". In Horwitz, Allan V.; Scheid, Teresa L. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 348–60.

- ↑ Bourdon, Karen H.; Boyd, Jeffrey H.; Rae, Donald S.; Burns, Barbara J.; Thompson, James W.; Locke, Ben Z. (1988). "Gender differences in phobias: Results of the ECA community survey". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2 (3): 227–241. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(88)90004-7.

- ↑ Breslau, N. "Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder". Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Seeman, Mary. "Psychopathology in Women and Men: Focus on Female Hormones". Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Potenza, Marc. "Gender-Related Differences in the Characteristics of Problem Gamblers Using a Gambling Helpline". Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Edited by Robin Dunbar and Louise Barret, Oxford University Press, 2007, Chapter 16 The evolution of empathizing and systemizing: assortative mating of two strong systemizers and the cause of autism, Simon Baron-Cohen.

- ↑ Schlomer, Gabriel L.; Del Giudice, Marco; Ellis, Bruce J. (2011). "Parent–offspring conflict theory: An evolutionary framework for understanding conflict within human families". Psychological Review. 118 (3): 496–521. doi:10.1037/a0024043. PMID 21604906.

- ↑ Badcock, Christopher; Crespi, Bernard (2008). "Battle of the sexes may set the brain". Nature. 454 (7208): 1054–5. Bibcode:2008Natur.454.1054B. doi:10.1038/4541054a. PMID 18756240.

- 1 2 Mansouri FA, Fehring DJ, Gaillard A, Jaberzadeh S, Parkington H (2016). "Sex dependency of inhibitory control functions". Biol Sex Differ. 7: 11. doi:10.1186/s13293-016-0065-y. PMC 4746892. PMID 26862388.

Inhibition of irrelevant responses is an important aspect of cognitive control of a goal-directed behavior. Females and males show different levels of susceptibility to neuropsychological disorders such as impulsive behavior and addiction, which might be related to differences in inhibitory brain functions. ... Here, we show a significant difference in executive control functions and their modulation by contextual factors between females and males

- ↑ Catharine P. Cross, Lee T. Copping and Anne Campbell. "Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis." PB 2009-0265-rrr 8/24/10. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5974/b6ef9af8cf03bcef5582d75aed8bb51e76a5.pdf

- ↑ Jessica Weafer, and Harriet de Wit. "Sex differences in impulsive action and impulsive choice." Addict Behav. 2014 Nov; 39(11): 1573–1579. Published online 2013 Nov 6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.033. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4012004/.

- ↑ King, Robert C. (2012). A dictionary of genetics (8. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 9780199766444.

- ↑ Zirkle, Conrad 1946. The discovery of sex-influenced, sex limited and sex-linked heredity. In Ashley Montagu M.F. (ed) Studies in the history of science and learning offered in homage to George Sarton on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. New York: Schuman, p167–194.

- 1 2 King R.C; Stansfield W.D. & Mulligan P.K. 2006. A dictionary of genetics. 7th ed, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530761-5

- 1 2 Sánchez FJ1 Vilain E.; Vilain, E (2010). "Genes and brain sex differences". Prog Brain Res. 186 (2010, 186): 65–76. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00005-1. PMID 21094886.

- 1 2 Margaret M. McCarthy; Anthony P. Auger; Tracy L. Bale; Geert J. De Vries; Gregory A. Dunn; Nancy G. Forger; Elaine K. Murray; Bridget M. Nugent; Jaclyn M. Schwarz; Melinda E. Wilson (Oct 14, 2009). "The Epigenetics of Sex Differences in the Brain". J. Neurosci. 29 (29(41)): 12815–12823. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3331-09.2009. PMC 2788155. PMID 19828794.