Selkie

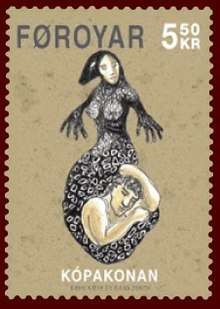

A Faroese stamp | |

| Grouping | Mythological |

|---|---|

| Similar creatures | |

| Habitat | Water |

Selkies (also spelled silkies, sylkies, selchies) or Selkie folk (Scots: selkie fowk) meaning "Seal Folk"[lower-alpha 1] are mythological beings capable of therianthropy, changing from seal to human form by shedding their skin.

These selkie folk are recounted in Scottish folklore, sourced mainly from Orkney and Shetland.

The folk-tales frequently revolve around female selkies being coerced into relationships with humans by someone stealing and hiding their sealskin, thus exhibiting the tale motif of the swan maiden type.

While "selkies" is the proper term for such shapeshifters according to an Orcadian folklorist, treatises on Shetland refer to them merely as mermen or merwomen.

There are counterparts in Faroese and Icelandic folklore that speak of seal-women and seal-skin. In some instances the Irish mermaid (merrow) is regarded as a half-seal, half-human being.

Terminology

The Scots word selkie is diminutive for selch which strictly speaking means "grey seal" (Halichoerus grypus). Alternate spellings for the diminutive include: selky, seilkie, sejlki, silkie, silkey, saelkie, sylkie, etc.[1]

The term "selkie" according to Alan Bruford should be treated as meaning any seal with or without the implication of transformation into human form.[2]

W. Traill Dennison insisted "selkie" was the correct term to be applied to these shapeshifters, to be distinguished from the merfolk, and that Samuel Hibbert committed an error in referring to them as "mermen" and "mermaids".[3] However, when other Norse cultures are examined, Icelandic writers also refer to the seal-wives as merfolk (marmennlar).[4]

There also seems to be some conflation between the selkie and finfolk. This confounding only existed in Shetland, claimed Dennison, and that in Orkney the selkie are distinguished from the finfolk, and the selkies' abode undersea is not "Finfolk-a-heem";[5] this notion, although seconded by Ernest Marwick,[6] has been challenged by Bruford.[7]

There is further confusion with the Norse concept of the Finns as shapeshifters,[7] "Finns" (synonymous with finfolk[8]) being the Shetlandic name for dwellers of the sea who could remove their seal-skin and transform into humans according to one native correspondent.[lower-alpha 2][10]

- Gaelic terms

In Gaelic stories, specific terms for selkies are rarely used. They are seldom differentiated from mermaids. They are most commonly referred to as maighdeann-mhara in Scottish Gaelic, maighdean mhara in Irish, and moidyn varrey in Manx [11] ("maiden of the sea" i.e. mermaids) and clearly have the seal-like attributes of selkies.[12] The only term which specifically refers to a selkie but which is only rarely encountered is maighdeann-ròin, or "seal maiden".[13]

Scottish legend

Many of the folk-tales on selkie folk have been collected from the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland).[14]

In Orkney lore, selkie is said to denote various seals of greater size than the grey seal; only these large seals are credited with the ability to shapeshift into humans, and are called "selkie folk".[15] Something similar is stated in Shetland tradition, that the mermen and mermaids prefer to assume the shape of larger seals, referred to as "Haaf-fish".[16]

Selkie wife and human lover

A typical folk-tale is that of a man who steals a female selkie's skin, finds her naked on the sea shore, and compels her to become his wife.[17] But the wife will spend her time in captivity longing for the sea, her true home, and will often be seen gazing longingly at the ocean. She may bear several children by her human husband, but once she discovers her skin, she will immediately return to the sea and abandon the children she loved. Sometimes, one of her children discovers or knows the whereabouts of the skin.[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] Sometimes it is revealed she already had a first husband from her own kind.[18][21] Although in some children's story versions, the selkie revisits her family on land once a year, in the typical folktale she is never seen again by them.[22] Sometimes the human will not know that their lover is a selkie, and wakes to find them returned to their seal form. In one version, the selkie wife was never seen again (at least in human form) by the family, but the children would witness a large seal approach them and "greet" them plaintively.[23]

Male selkies are described as being very handsome in their human form, and having great seductive powers over human women. They typically seek those who are dissatisfied with their lives, such as married women waiting for their fishermen husbands.[15] In one popular tattletale version about a certain "Ursilla" of Orkney (a pseudonym), it was rumored that when she wished to make contact with her male selkie would shed seven tears into the sea.[24]

Children born between man and seal-folk may have webbed hands, as in the case of the Shetland mermaid whose children had a "a sort of web between their fingers",[25] or "Ursilla" rumored to have children sired by a male selkie, such that the children had to have the webbing between their fingers and toes made of horny material clipped away intermittently. Some of the descendants actually did have these hereditary traits, according to Walter Traill Dennison who was related to the family.[26][27]

Binding rules and sinful origin

Some legends say that selkies could turn human every so often when the conditions of the tides were correct, but oral storytellers disagreed as to the time interval.[15] In Ursilla's rumor, the contacted male selkie promised to visit her at the "seventh stream" or springtide.[26] In the ballad The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry, the seal-husband promised to return in seven years; the number "seven" being commonplace in balladry.[28]

According to one version, the selkie could only assume human form once every seven years because they are bodies that house condemned souls.[20] There is the notion that they are either humans who had committed sinful wrongdoing,[15] or fallen angels.[15][25]

Orkney tales

The selkie-wife tale had its version for practically every island of Orkney according to W. Traill Dennison. In his study, he included a version collected from a resident of North Ronaldsay, in which a "goodman of Wastness", a confirmed bachelor, falls in love with a damsel among the selkie-folk, whose skin he captures. She searches the house in his absence, and finds her seal-skin thanks to her youngest daughter who had once seen it being hidden under the roof.[19]

In "Selkie Wife", a version from Deerness on the Mainland, Orkney, the husband locked away the seal-skin in a sea-kist (chest) and hid the key, but the seal woman is said to have acquiesced to the concealment, saying it was "better tae keep her selkie days oot o' her mind".[29] However, when she discovered her skin, she departed hastily leaving her clothes all scattered about.[27]

A fisherman named Alick supposedly gained a wife by stealing the seal-skin of a selkie, in a tale told by an Orkney skipper. The Alick in the tale is given as a good acquaintance of the father of the storyteller, John Heddle of Stromness.[20]

Shetland tales

A version of the tale about the mermaid compelled to become wife to a human who steals her seal-skin, localized in Unst, was published by Samuel Hibbert in 1822. She already had a husband of her own kind in her case.[18]

Some stories from Shetland have selkies luring islanders into the sea at midsummer, the lovelorn humans never returning to dry land.[30]

In the Shetland, the sea-folk were believed to revert to human shape and breathed air in the atmosphere in the submarine homeland, but with their sea-dress (seal-skin) they had the ability to transform into seals to make transit from there to the reefs above the sea. However, each skin was unique and irreplaceable.[16]

In the tale of "Gioga's Son", a group of seals resting in the Ve Skerries were ambushed and skinned by Papa Stour fishermen, but as these were actually seal-folk, the spilling of the blood caused a surge in seawater, and one fisherman was left abandoned. The seal-folk victims recovered in human-like form, but lamented the loss of their skin without which they could not return to their submarine home. Ollavitinus was particularly distressed since he was now separated from his wife; however, his mother Gioga struck a bargain with the abandoned seaman, offering to carrying him back to Papa Stour on condition the skin would be returned.[31] In a different telling of the same plot line, the stranded man is called Herman Perk, while the rescuing selkie's name is unidentified.[32]

Parallels

Tales of the seal bride type has been assigned the number ML 4080 under Reidar Thoralf Christiansen's system of classification of migratory folktales.[33][34] These stories of selkie-wives are also recognized to be of the swan maiden motif type.[35] There are now hundreds of seal bride type tales that have been found from Ireland to Iceland.[36] Only one specimen was found in Norway by Christiansen.[37]

In the Faroe Islands there are analogous beliefs in seal-folk and seal-women also.[38]

Seal shapeshifters similar to the selkie exist in the folklore of many cultures. A corresponding creature existed in Swedish legend, and the Chinook people of North America have a similar tale of a boy who changes into a seal.

Icelandic folk-tales

The folk-tale "Selshamurinn" ("The Seal-Skin") published by Jón Árnason offers an Icelandic analogue of the selkie folk tale.[39] The tale relates how a man from Mýrdalur forced a woman transformed from a seal to marry him after taking possession of her seal-skin. She discovers the key to the chest in her husband's usual clothes when he dresses up for a Christmas outing, and the seal woman is reunited with the male seal who was her betrothed partner.[40][41][42]

Another such tale was recorded by Jón Guðmundsson the Learned (in 1641), and according to him these seal folk were sea-dwelling elves called marmennlar (mermen and mermaids).[4]

Faroese legends

In the Faroe Islands there are two versions of the story of the 'seal wife'. A young farmer from the town of Mikladalur on Kalsoy island goes to the beach to watch the selkies dance. He hides the skin of a beautiful selkie maid so she cannot go back to sea, and forces her to marry him. He keeps her skin in a chest, and keeps the key with him both day and night. One day when out fishing, he discovers that he has forgotten to bring his key. When he returns home, the selkie wife has escaped back to sea, leaving their children behind. Later, when the farmer is out on a hunt, he kills both her selkie husband and two selkie sons, and she promises to take revenge upon the men of Mikladalur. Some shall be drowned, some shall fall from cliffs and slopes, and this shall continue, until so many men have been lost that they will be able to link arms around the whole island of Kalsoy. There are still occasional deaths occurring in this way on the island.

Peter Kagan and the Wind by Gordon Bok tells of the fisherman Kagan who married a seal-woman. Against his wife's wishes he set sail dangerously late in the year, and was trapped battling a terrible storm, unable to return home. His wife shifted to her seal form and saved him, even though this meant she could never return to her human body and hence her happy home.

Irish folklore

The mermaid in Irish folkore (sometimes called "merrow" in Hiberno-English) have been regarded as a seal-woman in some instances. In a certain collection of lore in County Kerry, there is an onomastic tale in Tralee which claimed the Lee family was descended from a man who took a murdúch (mermaid) for a wife; she later escaped and joined her seal-husband, suggesting she was of the seal-folk kind.[43]

There is also the tradition that the Conneely clan of Connemara was descended from seals, and it was taboo for them to kill the animals lest it bring ill luck. And since "conneely" became a moniker of the animal, many changed their surname to Connelly.[44][45] It is also mentioned in this connection that there is a Roaninish (Rón-inis, "seal island") off Donegal, outside Gweebarra Bay.[46]

Theories of origins

Before the advent of modern medicine, many physiological conditions were untreatable. When children were born with abnormalities, it was common to blame the fairies.[47] The MacCodrum clan of the Outer Hebrides became known as the "MacCodrums of the seals" as they claimed to be descended from a union between a fisherman and a selkie. This was an explanation for their syndactyly – a hereditary growth of skin between their fingers that made their hands resemble flippers.[48]

Scottish folklorist and antiquarian, David MacRitchie believed that early settlers in Scotland probably encountered, and even married, Finnish and Sami women who were misidentified as selkies because of their sealskin kayaks and clothing.[48] Others have suggested that the traditions concerning the selkies may have been due to misinterpreted sightings of Finn-men (Inuit from the Davis Strait). The Inuit wore clothes and used kayaks that were both made of animal skins. Both the clothes and kayaks would lose buoyancy when saturated and would need to be dried out. It is thought that sightings of Inuit divesting themselves of their clothing or lying next to the skins on the rocks could have led to the belief in their ability to change from a seal to a man.[49]

Another belief is that shipwrecked Spaniards were washed ashore, and their jet black hair resembled seals.[50] As the anthropologist A. Asbjørn Jøn has recognised, though, there is a strong body of lore that indicates that selkies "are said to be supernaturally formed from the souls of drowned people".[51]

Modern treatments

Scottish poet George Mackay Brown wrote a modern prose version of the story, entitled "Sealskin".[52]

In popular culture

Selkies—or references to them—have appeared in numerous novels, songs and films, though the extent to which these reflect traditional stories varies greatly. Work where selkie lore forms the central theme include:

- A Stranger Came Ashore, a young adult novel by Scottish author Mollie Hunter. Set on the Shetland Islands in the north of Scotland, the plot revolves around a boy who must protect his sister from the Great Selkie.

- Song of the Sea, an Irish animated film about a young boy who must deal with the disappearance of his selkie mother and his resentment of his sister, born when his mother disappeared.

- The Secret of Roan Inish, a 1994 American/Irish independent film based on the novel Secret of the Ron Mor Skerry, by Rosalie K. Fry. The film's story follows a young girl who uncovers the mystery of her family's Selkie ancestry, and its connection to her lost brother.

- Selkie, a 2000 Australian made-for-TV film.

- Anchor, a song by Novo Amor is inspired by the legend of the selkie. The video produced by Storm and Shelter features a fisherman who finds a woman at sea and rescues her, taking her home. However, her true home is the sea.[53]

- My Hero Academia, contains a character named Selkie who possesses seal-like abilities and appearance.

- In the Magic: The Gathering card game, selkies are a type of blue/green-aligned merfolk, native to the plane of Shadowmoor. They are unknown from the "sunny" counterpart to Shadowmoor, Lorwyn.

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ selkie simply means "seal" in Scots dialect. Bruford (1974), p. 78, note 1. Bruford (1997), p. 120.

- ↑ George Sinclair Jr., an informant for Karl Blind. This intelligence about the "Finns" was also repeated by Francis James Child in his annotation to ballad 113, "The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry".[9]

- ↑ The child with a sore on her feet reveals it to be in the aisins (space beneath the eaves) in the Orkney version from North Ronaldsay, the mother told the child she was looking for the skin for her, so she could make a rivlin (shoe) to heal her sore.

- ↑ The children found the skin under a sheaf of corn (wheat or other grain) in the tale about the man of Unst, Shetland.

References

- ↑ "Selch". Scottish National Dictionary. DSL. 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Bruford (1974), p. 78, note 1: "A selkie is simply a seal, though readers of the ballad [on the selkie] have tended to assume that in itself it means a seal which can take human form". Bruford (1997), p. 120: "‘selkie’ in itself does not imply the ability to take human form any more than ‘seal’ does".

- ↑ Dennison (1893), p. 173.

- 1 2 Jón Árnason (1866). Icelandic Legends Collected by Jón Árnason. Translated by George E. J. Powell; Eiríkr Magnússon. London: Longman, Green, and Co. pp. xliii–xliv. ; [Islenzkar þjóđsögur] I, pp. XII–XIV

- ↑ Dennison (1893), pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Marwick, Ernest W. (1975) The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland, London, B. T. Batsford: "in Shetland, Fin Folk and Seal Folk were frequently confused, but in Orkney they were completely distinguished", p. 25, cf. pp. 48–49, quoted by Burford

- 1 2 Bruford (1997), p. 121.

- ↑ "Finn". Scottish National Dictionary. DSL. 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Child, Francis James, ed. (1886). "113 The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry". The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. II. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin. p. 494.

- ↑ Blind, Karl (1881). "Scottish, Shetlandic, and Germanic Water Tales (Part II)". The Contemporary Review. 40: 403–405.

- ↑ Fargher, C. English Manx-Dictionary Shearwater Press 1979

- ↑ MacIntyre, Michael (1972). "Maighdeann-mhara a' tionndadh na boireannach". School of Scottish Studies (in Scottish Gaelic). Tobar an Dualchais. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Fleming, Cirsty Mary (1973). "A' mhaighdeann-ròin a chaidh air ais dhan mhuir". School of Scottish Studies (in Scottish Gaelic). Tobar an Dualchais. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ↑ Westwood, Jennifer & Kingshill, Sophia (2011). The Lore of Scotland: A guide to Scottish legends. Arrow Books. pp. 404–405. ISBN 9780099547167.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dennison (1893), p. 172.

- 1 2 Hibbert (1891), p. 261.

- ↑ Hiestand (1992), p. 331: "Those are always the basic ingredients: an unmarried farmer, a seal-skin, a naked woman in the waves".

- 1 2 Shetland version localized in Unst: Hibbert (1891), pp. 262–263; Keightley (1850), pp. 169–171: "The Mermaid Wife".

- 1 2 Dennison (1893), pp. 173–175.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy, Capt. Clark (July 1884). "Wild Sport in the Orkney Isles". Baily's Magazine of Sports & Pastimes. 42: 355–356, 406–407.

- ↑ Orcadian versions: Dennison (tale from North Ronaldsay);[19] Capt. Clark Kennedy (1884, tale from Stromness skipper)[20]

- ↑ Hiestand (1992), p. 332.

- ↑ Pottinger (1908), "Selkie Wife" (from Deerness, Orkney), p. 175.

- ↑ Dennison (1893), pp. 175–176: Dennison believed it to be "an imaginary tale, invented by gossips".

- 1 2 Hibbert (1891), p. 264.

- 1 2 Dennison (1893), p. 176.

- 1 2 McEntire (2007), p. 128.

- ↑ Wimberly, Louis Charles (1921). Minstrelsy, Music, and the Dance in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism, 4. Linconln: U of Nebraska. p. 89.

- ↑ Pottinger (1908), pp. 173–175

- ↑ Hardie, Alison (20 January 2007). "Dramatic decline in island common seal populations baffles experts". The Scotsman. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ↑ Hibbert (1891), pp. 262–263; Keightley (1850), pp. 167–169: "Gioga's son".

- ↑ Nicolson, John (1920) "Herman Perk and the Seal",Some Folk-Tales and Legends of Shetland, Edinburgh: Thomas Allan and Sons, pp. 62–63. Cited by Ashliman, D. L. (2000–2011), "The Mermaid Wife"

- ↑ Bruford (1997), pp. 121–122.

- ↑ McEntire (2007), p. 126.

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia (2009). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing. p. 411. ISBN 978-1438110370.

- ↑ Berry, Robert James; Firth, Howie N. (1986). The People of Orkney. Orkney Press. pp. 172, 206. ISBN 9780907618089. . Cited by

- ↑ Bruford (1997), p. 122.

- ↑ Spence, Lewis (1972) [1948]. The Minor Traditions of British Mythology. Ayer Publishing. pp. 50–56.

- ↑ Ása Helga Ragnarsdóttir, assistant lecturer at University of Iceland, cited in Booth, David (2014). Exploding the Reading: Building a world of responses from one story. Markham, Ontario: Pembroke Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8131-0939-8. .

- ↑ Jón Árnason (1862), pp. 632–634 "Selshamurinn"; Jón Árnason & Simpson (tr.) (1972), pp. 100–102 "The Seal's Skin "; Jón Árnason & Boucher (tr.) (1977), pp. 81–82 "The Seal-Skin", etc.

- ↑ Ashliman (tr.) (2000) "The Sealskin".

- ↑ "The Seal's Skin: Icelandic Folktale". The Viking Rune. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ↑ Domhnall Ó Murchadha Rannscéalta (1920), cited by Gilchrist (1921), p. 263

- ↑ Kinahan G. H., "Connemara Folk-Lore", Folk-Lore Journal II: 259; Folklore Record IV: 104. Cited and quoted by Gomme, G. L. (June 1889). "Totemism in Britain". Archaeological Review. 3 (4): 219–220.

- ↑ The Coneely case and other merrow lineage connected to selkie wife by MacRitchie, David (1890). Testimony of Tradition. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 15, n3.

- ↑ Gomme (1889), p. 219, n3, citing Joyce, P. W. (1883) Origin and History of Irish Names of Places 2: 290.

- ↑ Eason, Cassandra (2008). "Fabulous creatures, mythical monsters and animal power symbols". Fabulous creatures, mythical monsters, and animal power symbols: a handbook. pp. 147–48. ISBN 9780275994259. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- 1 2 Garry, Jane; El-Shamy, Hasan. "Animal brides and grooms". Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. p. 97. ISBN 9780765629531. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Towrie, Sigurd. "The Origin of the Selkie-folk: Documented Finmen sightings". Orkneyjar.com. Sigurd Towrie. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Silver, Carole B. (1999). Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-512199-5.

- ↑ Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1998). Dugongs and Mermaids, Selkies and Seals. Australian Folklore. 13. pp. 94–98. ISBN 978-1-86389-543-9.

- ↑ Brown, George Mackay (1983), "Sealskin", A Time to Keep and Other Stories, New York, Vanguard Press, pp. 172–173, cited in Hiestand (1992), p. 330.

- ↑ "Novo Amor reinterprets the Selkie legend with music video for "Anchor" — watch". Consequence of Sound. 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- Bibliography

- Bruford, Alan (1974). "The Grey Selkie". Scottish Studies. 18: 63–81.

- Bruford, Alan (1997). Narvez, Peter, ed. Trolls, Hillfolks, Finns and Picts. The Good People: New Fairylore Essays. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-0-8131-0939-8.

- Dennison, W. Traill (1893). "Orkney Folk-Lore". The Scottish Antiquary, or, Northern Notes and Queries. 7: 171–177. JSTOR 25516580

- Gilchrist, A. G. (January 1921). Freeman, A. Martin. "Extra Note on Song No. 48, verse 7". Journal of the Folk-Song Society. 6 (2): 266 (263–266). JSTOR 4434091

- Hibbert, Samuel (1891) [1822]. A Description of the Shetland Islands:. T. & J. Manson.

- Hiestand, Emily Hiestand (Summer 1992). "South of the Ultima Thule". The Georgia Review. 46 (2): 289–343. JSTOR 41400296

- Jón Árnason (1862), "Selshamurinn", Íslenzkar Þjóðsögur og Æfintýri, Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, I, pp. 632–634

(in Icelandic)

- Jón Árnason (April 1997). "Selshamurinn". Íslenzkar Þjóðsögur og Æfintýri. Retrieved 2018-06-06. (in Icelandic)

- Jón Árnason (1977). The Seal-Skin. Elves, Trolls and Elemental Beings: Icelandic Folktales II. Translated by Alan Boucher. London: Iceland Review Library. pp. 81–82.

- Jón Árnason (1972). The Seal's Skin. Icelandic Folktales and Legends. Translated by Jacqueline Simpson. University of California Press. pp. 100–102. ISBN 9780520021167.

- Jón Árnason (2007). The Sealskin. Icelandic folk and fairy tales. Translated by May Hallmundsson; Hallberg Hallmundsson. Reykjavik: Almenna bókafélagið. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9789979510444.

- "The Sealskin". Professor D. L. Ashliman. Translated by D. L. Ashliman. 2000. (translated from the German)[1]

- McEntire, Nancy Cassell (2007). "Supernatural Beings in the Far North: Folklore, Folk Belief, and the Selkie". Scottish Studies. 35: 120–143.

- Pottinger, J. A. (1908), "The Selkie Wife", Orkney and Shetland Miscellany, Viking Club, 1 (5), pp. 173–175

- Keightley, Thomas (1850) [1828], The Fairy Mythology: Illustrative of the Romance and Superstition of various Countries (new revised ed.), H. G. Bohn, pp. 167–171

- Further reading

- Williamson, Duncan (1992). Tales of the seal people: Scottish folk tales. New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 978-0-940793-99-6.

- Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1998). Dugongs and Mermaids, Selkies and Seals. Australian Folklore. 13. pp. 94–98. ISBN 978-1-86389-543-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Selkies. |

- The Mermaid Wife and other migratory legends of Christiansen type 4080 tr. ed. D. L. Ashliman

- Annotated Selkie resources from Mermaids on the Web

- A Home for Selkies by Beth Winegarner

- Some pictures from the play Kópakonan (the Seal-Wife), which was performed by children at the theatre in Tórshavn in May 2001

- The First Silkie by William Meikle, read on the Celtic Myth Podshow