School corporal punishment in the United States

Corporal punishment, also referred to as "physical punishment" or "physical discipline,"[2] is defined as utilizing physical force, no matter how light, to cause deliberate bodily pain or discomfort in response to some undesired behavior.[3] In schools in the United States, this punishment often takes the form of either a teacher or school principal striking the student's buttocks with a wooden paddle (sometimes called "spanking").[2]

The practice was held constitutional in the 1977 Supreme Court case Ingraham v. Wright, where the Court held that the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause of the Eighth Amendment did not apply to disciplinary corporal punishment in public schools, being restricted to the treatment of prisoners convicted of a crime.[4] In the years since, a number of U.S. states have banned corporal punishment in public schools,[2] with the most recent state to outlaw school corporal punishment being New Mexico in 2011.[5]

As of 2014, a student is hit in a U.S. public school an average of once every 30 seconds.[6]

History of corporal punishment in U.S. schools

Corporal punishment was widely utilized in U.S. schools during the 19th and 20th centuries as a way to motivate students to perform better academically and maintain objectively good standards of behavior.[7] The practice was generally considered a fair and rational way to discipline school children, particularly given its parallels to the criminal justice system, and teachers in the late 19th century were encouraged to employ corporal punishment over other types of discipline.[8] In the English-speaking world, the right of teachers to discipline children is enshrined in the common-law doctrine in loco parentis (Latin for "in the place of parents"), which places a legal responsibility on authority-holders to take on the functions of a parent in some instances.[9]

Some of the earliest parental opposition to corporal punishment in schools occurred in England in 1899 in the case Gardiner v. Bygrave,[7] in which a teacher in London was acquitted after a parent took him to court for assault after he physically punished their son. This case set a precedent that schools could discipline children in the way they saw fit, regardless of the wishes of the parent regarding the physical punishment of their child. Over the next century, the conception of corporal punishment as a common component of disciplining students in public schools would be challenged in various countries, but opposition to corporal punishment it schools wouldn't make it to the U.S. Supreme Court until 1977.

Federal stance

In 1977, the question of the legality of corporal punishment in schools was brought to the Supreme Court. At this point, only New Jersey (1867), Massachusetts (1971), Hawaii (1973), and Maine (1975) had outlawed physical punishment in public schools, and just New Jersey had also outlawed the practice in private schools. Many assumed that the Supremes would rule in favor of the plaintiffs.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of corporal punishment in schools in the landmark Ingraham v. Wright case. The Supremes ruled 5-4 that the corporal punishment of James Ingraham, who was restrained by his assistant principal and paddled by the principal over 20 times, ultimately requiring medical attention, did not constitute the Eighth Amendment, which protects citizens from cruel and unusual punishment. They further concluded that corporal punishment did not violate the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, since teachers or administrators administering excessive punishment can face criminal charges.[4][10] This case established a precedent of "reasonable, but not excessive" punishment of students and was criticized by some scholars as "an apparent low point in American teacher-student relations."[11]

The Ingraham v. Wright ruling firmly pushed the decision of whether or not to outlaw corporal punishment in schools squarely onto state legislators. A majority of state bans on corporal punishment have occurred in the intervening years since 1977.

States' stance

Individual states have had the power to ban corporal punishment in public schools since the 19th century. Each state has the authority to define corporal punishment in its state laws, so bans on corporal punishment differ from state to state.[12] For example, in Texas, teachers are permitted to paddle children and to use "any other physical force" to control children in the name of discipline;[13] in Alabama, the rules are more explicit: teachers are permitted to use a "wooden paddle approximately 24 inches in length, 3 inches wide and ½ inch thick."[14]

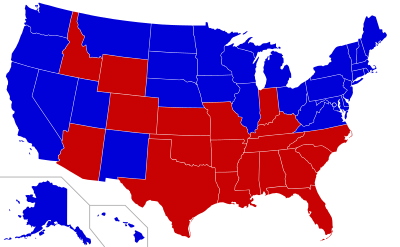

The first state to abolish school corporal punishment was New Jersey in 1867.[2] In 1894, a Newark bill challenged this ruling, arguing that whipping should be legal if parents consented to it; the New Jersey House defeated that bill, with one doctor's testimonial asserting that the bill's provisions "would expose children who did not have thoughtful and careful parents to the cruel discrimination of the teachers."[15] The second state to ban corporal punishment in schools was Massachusetts, 104 years later in 1971. As of 2015, corporal punishment is banned in state schools (known as public schools in the U.S.) in 31 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (see list below).[5] The usage of corporal punishment in private schools is legally permitted in nearly every state, though extremely uncommon in most, with only New Jersey[16] and Iowa[17] prohibiting it in both public and private schools. Corporal punishment is still used in schools to a significant (though declining)[18] extent in some public schools in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee, North Carolina and Texas. The most recent state to outlaw school corporal punishment was New Mexico in 2011.[5]

The majority of students who experience corporal punishment reside in the Southern United States; Department of Education data from 2011–2012 show that 70 percent of students subjected to corporal punishment were from the five states of Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas, with the latter two states accounting for 35 percent of corporal punishment cases.[19][5]

Students can be physically punished from kindergarten to the end of high school, meaning that even legal adults who have reached the age of majority are sometimes spanked by school officials.[20] However, a majority of states that permit corporal punishment require that parental consent be given before children may be paddled. In these states, parents are sometimes (but not always) given the option of physical punishment of their child instead of alternate disciplinary measures, like suspension.[12]

Current stance in public/private schools

List of U.S. states outlawing corporal punishment in public schools

- Alaska - 1989

- California – 1986

- Connecticut – 1989

- Delaware – 2003

- District of Columbia – 1977

- Hawaii – 1973

- Illinois – 1994[21]

- Iowa – 1989

- Maine – 1975

- Maryland – 1993

- Massachusetts – 1971

- Michigan – 1989

- Minnesota – 1989

- Montana – 1991

- Nebraska – 1988

- Nevada – 1993

- New Hampshire – 1983

- New Jersey – 1867[22][23]

- New Mexico – 2011

- New York – 1985

- North Dakota – 1989

- Ohio – 2009[24]

- Oregon – 1989

- Pennsylvania – 2005

- Rhode Island – 1977

- South Dakota – 1990

- Utah – 1992[25]

- Vermont – 1985

- Virginia – 1989

- Washington – 1993

- West Virginia – 1994

- Wisconsin – 1988

List of U.S. states outlawing corporal punishment in private schools

- New Jersey - 1867

- Iowa - 1989

Trends in the use of corporal punishment in schools

| Alabama | Idaho | Missouri | Wyoming |

| Arkansas | Indiana | North Carolina | |

| Arizona | Kansas | Oklahoma | |

| Colorado | Kentucky | South Carolina | |

| Florida | Louisiana | Tennessee | |

| Georgia | Mississippi | Texas |

The prevalence of school corporal punishment has decreased since the 1970s, declining from 4 percent of the total number of children in schools in 1978 to less than 1 percent in 2014. This reduction is partially explained by the increasing number of states banning corporal punishment from public schools between 1974 and 1994.[26]

The number of instances of corporal punishment in U.S. schools have also declined in recent years. In the 2002-2003 school year, federal statistics estimated that 300,000 children were disciplined with corporal punishment at school at least once. In the 2006-2007 school year, this number was reduced to 223,190 instances.[27] According to the Department of Education, over 166,000 students in public schools were physically punished during the 2011–2012 school year.[28] In the 2013-2014 academic year, this number was reduced to 109,000 students.[29]

As of the 2011-2012 academic year, 19 states legally allowed school corporal punishment. Approximately 14 percent of the schools in those 19 states reported the use of corporal punishment, and 1 in 8 students attended schools that use this practice.[26]

Behaviors that elicit corporal punishment in schools

Several studies have explored which behaviors elicit corporal punishment as a response, but so far there is not a cohesive and standardized system use within states or across states. The Human Rights Watch conducted a series of interviews with paddled students and teachers in Mississippi and Texas and found that most of school corporal punishment was for minor infractions, such as violating the dress code, being tardy, talking in class, running in the hallway and going to the bathroom without permission.[30] A review of over 6,000 disciplinary files in Florida for 1987-1988 school year found that corporal punishment use in schools was not related to the severity of student's misbehavior or with the frequency of the infraction.[31] Czumbil and Hyman reviewed over 500 media stories about corporal punishment in newspapers from 1975 to 1992 and coded the reason of the punishment and its severity. They found that the nature of the child's misbehavior (violent or non-violent) did not meaningfully influence whether the student was physically punished or not.[32]

Disparities

Many studies have found that there are extreme disparities in the physical punishment of students across racial and ethnic lines, gender and disability status.[33][13] In general, results suggest that boys, children of color and children with disabilities are most likely to be targets of corporal punishment.[13] These disparities may violate three federal laws that prohibit discrimination by race, gender and disability status: Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.[26]

By gender

At the turn of the 20th century, both boys and girls received roughly equal levels of corporal punishments in U.S. schools, but girls were more likely to report their punishment as 'unjust' or 'unfair.' However, while punishment was seen as a builder of masculinity for boys, girls were not expected to experience the same benefits, so their punishment was often, but not always, more lenient.[7] This trend in gender parity changed significantly in the next century.

Today, boys are more likely than girls to be physically punished in schools, and this disparity has persisted for decades.[26] In 1992, boys accounted for 81 percent of all incidents of physical discipline in schools.[34] By 2012, the majority of school districts within states that legally allow corporal punishment registered a ratio of 3:1 or higher, indicating that boys are 3 times more likely than girls to experience corporal punishment.[26] Differences in behavior (and perceived behavior) can explain a fraction of this imbalance, but does not account for the entire discrepancy between the genders. Boys have been found to be two times as likely as girls to be disciplined for misbehavior in school, but they are four times as likely to be disciplined using corporal punishment.[26][35]

When race and gender are considered together, black boys are 16 times as likely to be subject of corporal punishment as white girls.[34] Among children with disabilities, black boys have the highest probability of being subject to corporal punishment, followed by white boys, black girls and white girls. While black boys are 1.8 times as likely as white boys to be physically punished, black girls are 3 times more likely than white girls.[26]

By race or ethnicity

The race and ethnic disparities in school corporal punishment have decreased within groups over time, but the relative prevalence of corporal punishment between groups has remained stable.[26] Black students are physically punished at higher rates than white or Hispanics. In contrast, Hispanic students are less likely than white students to receive corporal punishment. One study found that African-American students were more likely than either white or Hispanic students to be physically punished, by 2.5 times and 6.5 times respectively.[36] Another study calculated the proportion of Black students who were physically punished to the proportion of white students who were by state, and found that for the 2011-2012 academic year, black children in Alabama and Mississippi were over 5 times more likely to be disciplined with corporal punishment than their white counterparts. In other southeastern states -Florida, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana and Tennessee- black children were more than 3 times more likely to receive corporal punishment than white children.[13]

A review of over 4,000 discipline events in Florida from 1987-1989 across nine schools revealed that, although Black students constituted 22 percent of school enrollment, they accounted for over 50 percent of all cases of corporal punishment.[37] The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction in 2013 published a review of corporal punishment cases in the 2011-2012 academic year founding that corporal punishment was disproportionately applied to Native American students, who represented 58 percent of all cases of corporal punishment while being only 2 percent of the student population.[38]

The disparity by race in the use of corporal punishment in schools goes in line with findings of other methods of discipline, where Black children are 2 to 3 times more likely than white children to be suspended or expelled from schools. According to a study by the American Psychological Association, these imbalances are not due to a higher likelihood of misbehaving by children of one race over another, or the socio-economic status of the children.[39]

By disability status

Children with physical, mental, or emotional disabilities are afforded special protections and services in U.S. public schools.[40] However, they are not afforded protection from school corporal punishment in the states that allow it, and in many states they are actually at greater risk for receiving corporal punishment than their non-disabled peers.[26] According to a report jointly authored by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union, the United States Department of Education's Civil Rights Data Collection for 2006 shows that students with disabilities are subjected to corporal punishment at disproportionately high rates for their share of the population.[41] Representative Carolyn McCarthy remarked in a 2010 congressional hearing that students with disabilities are subjected to corporal punishment at "approximately twice the rate of the general student population in some States."[42]

Children with disabilities are 50 percent more likely to experience school corporal punishment in more than 30% of the school districts in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee. However, in some school districts among Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, children with disability status are 5 times more likely to be subject of corporal punishment than peers without disabilities.[26]

Effects on children

Although there is literature on the effects of parental use of corporal punishment on health and school performance, corporal punishment in schools has been understudied. There are correlational studies that linked the use of corporal punishment in schools with detrimental physical and psychological effects on children, and also provide evidence about its long-term effects.[13]

According to these studies, children exposed to school corporal punishment are more likely to have conduct disorder problems, to experience feelings of inadequacy and resentment, to be more aggressive and violent, and to experience reduced problem-solving abilities, social competence and academic achievement.[43] Other studies have suggested that corporal punishment in schools can deter children's cognitive development, as children subject to corporal punishment in schools have a more restricted vocabulary, poorer school marks, and lower IQ scores.[44] Moreover, disparities in the use of corporal punishment among gender, race and disability status can be perceived by children as discrimination. This perceived discrimination has been related with lower self-esteem, lower positive mood, higher depression and anxiety.[45] These effects can also manifest as low academic engagement and more negative school behaviors, which exacerbate the existing gap in discipline policies along race and gender lines.[46]

Researchers have found a negative correlation between legality of corporal punishment and test scores. Students who are not exposed to school corporal punishment exhibit better results on the ACT test compared to students in states that allow disciplinary corporal punishment in schools.[47] In 2010, 75 percent of states that allow corporal punishment in schools scored below average on the ACT composite, while three-quarters of non-paddling states scored above the national average. Improvement trend among the years also differ, in the last 18 years 66 percent non-paddling states have above average rates of improvement, while 50 percent of spanking states were above the national trend of improvement.[47]

Furthermore, while corporal punishment is sometimes lauded as an alternative to suspension, the lack of formal training for U.S. teachers means that there is no consistently implemented style of corporal punishment that takes into account the size, age, or psychological profile of students. This leaves students more vulnerable to physical and psychological injury.[29]

Controversy

Public opinion in the U.S.

Public-opinion research has found that most Americans are not in favor of school corporal punishment; in polls taken in 2002 and 2005, American adults were respectively 72% and 77% opposed to the use of corporal punishment by teachers.[48] Moreover, a national survey conducted on teachers ranked corporal punishment as the lowest effective method to discipline offenders among eight possible techniques.[49]

A bill to end the use of corporal punishment in schools was introduced into the United States House of Representatives in June 2010 during the 111th Congress.[50][51] The bill, H.R. 5628,[52] was referred to the United States House Committee on Education and Labor where it was not brought up for a vote. A previous bill "to deny funds to educational programs that allow corporal punishment"[53] was introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives in 1991 by Representative Major Owens. That bill, H.R. 1522, did not become law. A new bill, the Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools Act of 2015 (HR 2268) would prohibit all corporal punishment, defined as "paddling, spanking, or other forms of physical punishment, however light, imposed upon a student", the petition was closed. In 2017, Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools Act of 2017 was introduced, and was referred to the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.[54]

The United States' National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) opposes the use of corporal punishment in schools, defined as the deliberate infliction of pain in response to students' unacceptable behavior and/or language. In articulating their opposition, they cite the disproportionate use of corporal punishment on Black students in the US: potential adverse effects on students' self-image and school achievement, correlation between school corporal punishment and increased truancy, drop-out rates, violence, and vandalism by youth, the potential for misuse and/or injury to students, and increased legal liability for schools. The NASSP notes that the use of corporal punishment in schools is inconsistent with laws regarding child abuse as well as policies toward "racial, economic, and gender equity", asserting that "Fear of pain or embarrassment has no place" in the process of education. The NASSP recommends a range of alternatives to corporal punishment, including "appropriate instruction", "behavioral contracts", "positive reinforcement", and "individual and group counseling" where necessary.[55]

Some scholars note a severe legal double-standard when it comes to the physical punishment of children versus adults. In North Carolina, teachers can use a 2-foot long paddle to discipline children, which, in some cases, is more than half the height of an elementary school-aged child.[56] "In any other context, the act of an adult hitting another person with a board [2 feet long] (or really, of any size) would be considered assault with a weapon and would be punishable under criminal law."[13]

However, some teachers and administrators defend the use of corporal punishment in the classroom as a reasonable alternative to other types of disciplinary action, like suspension, which have been shown to negatively impact children's classroom performance and social skills.[57] Some students, when given the choice between an in-school suspension and corporal punishment, choose to be physically punished in lieu of missing class time.[12]

The student's choice in favor of corporal punishment is often dictated by the parents and by the fact that a corporal punishment is not reported on student's personal record, when a suspension is duly recorded and can jeopardize the access to the university. Often students accept a physical punishment as a way to erase the record of the infraction.

In March 2018 the mother of Wylie Greer, a senior year student, has published a Tweet that become viral, she reported that during national gun control student walkout, his son with two other students walked out of class in Greenbrier High School, Arkansas. The same day the Assistant principal Mr Brett Meek informed Wylie of the consequences, two days of suspension or two "swats" with a wooden paddle. Wylie chose the corporal punishment. During a nationwide protest in favor of a more strict gun control, Wylie described the experience more humiliating than painful, but he reported that Mr Meek warned him that it was a particularly light punishment, somehow to avoid further bad publicity to the school. Akansas is one of the states where even senior students above 18 year old, can be paddled in school.

In 2018 case Ayers v Wells where Mr Ayers, Assistant principal in Etowah middle school in Alabama, is accused of excessive use of force during paddling incident in 2016, judge William Ogletree refused to dismiss the charges of child abuse against Mr Ayers and argued that immunity laws cannot be an excuse for using disproportionate force during punishments, raising for the first time a legal limit to immunity laws and school corporal punishments in Alabama.

In September 2018 The Georgia School of Innovation and the Classics in Georgia, sparkled controversy when the superintendent Jody Boulineau, reintroduced corporal punishments asking consent from parents. Sign of a mentality change, only one third of the parents agreed. Mr Boulineau in a interview to CBS said that he was really surprised of the outrage from some parents, at the same time the rate of the school went down 2 points in Google review and several parents posted online the willing to find school alternatives as they fear for their children safety. By comments massively posted as from 09/12/2018 on Google review, the school is engaged in a counter evaluation campaign.

On October 3 2018 Gary L. Gunckel, the principal of schools in Indianola, Oklahoma had been charged with two counts of felony child assault after paddling that left two boys with deep bruises. One of the children felt on the ground during paddling, Gunckel apologized to one of the mothers for busting the boys. Once more, parents that gave consent for paddling realize too late that school corporal punishments can be way harder than any home allowed corporal punishment. In the light of recent events it is indeed almost impossible to draw a line between punishment and child abuse and it is impossible to determine some standard on how hard a kid could be punished without committing a crime. Supreme Court sentence Ingraham v. Wright appears to be more and more outdated facing growing hostility from parents towards consequences of corporal punishments in school. Gunckel has been placed on administrative leave.

See also

References

- ↑ Anderson, Melissa (15 December 2015). "Where Teachers Are Still Allowed to Spank Students". The Atlantic.

- 1 2 3 4 Gershoff, E.T. (2008). Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children (PDF). Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

- ↑ Gershoff, E.T. (2017). School corporal punishment in global perspective: prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention (PDF). 22. Journal on Psychology, Health and Medicine. pp. 224–239. doi:10.1080/13548506.2016.1271955. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- 1 2 Oluwole, Joseph (23 September 2014). "Ingraham v. Wright". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- 1 2 3 4 Lyman, Rick (30 September 2006)."In Many Public Schools, the Paddle Is No Relic". The New York Times.

- ↑ Strauss, Valerie (18 September 2014). "19 states still allow corporal punishment in school". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 3 Middleton, Jacob. The Experience of Corporal Punishment in Schools, 1890–1940, History of Education, Vol. 37, No. 2, March 2008, pp. 253–275

- ↑ Landon, Joseph. The Principles and Practice of Teaching and Class Management, Alfred M. Holdon, 1899.

- ↑ Don R. Bridinger, (1957). "Discipline by Teachers in Loco Parentis" Cleveland State Law Review.

- ↑ Irwin A. Hyman; James H. Wise "Corporal Punishment in American Education: Readings in History, Practice, and Alternatives". Corporal Punishment in American Education: Readings in History, Practice, and Alternatives, Temple University Press, 1979.

- ↑ Debran Rowland "The Boundaries of Her Body: The Troubling History of Women's Rights in America". The Boundaries of Her Body: The Troubling History of Women's Rights in America Sphinx Pub, 2004.

- 1 2 3 Clark, Jess (April 2017). "Where Corporal Punishment Is Still Used In Schools, Its Roots Run Deep". www.npr.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Font, Sarah A. (2016). "Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy". Social policy report. 30. ISSN 1075-7031. PMC 5766273. PMID 29333055.

- ↑ Pickens County Board of Education (2015). "The Pickens County Board of Education Board Policy Manual."

- ↑ NY Times Editorial (20 March 1894)."New-Jersey House Says Newark Teachers Shall Not Use the Rattan.". The New York Times.

- ↑ United States - Extracts from State legislation at World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ↑ Iowa statutes, 280.21.

- ↑ "Corporal Punishment and Paddling Statistics by State and Race", Center for Effective Discipline.

- 1 2 Anderson, Melinda (15 December 2015). "Where Teachers Are Still Allowed to Spank Students". The Atlantic.

- ↑ C. Farrell (October 2016). "Corporal punishment in US schools". www.corpun.com.

- ↑ Chapman, Stephen (28 April 1994). "Singapore's Form Of Punishment Has Its Place In America". Chicago Tribune.

This year, Illinois has a new law that prohibits public schools from 'slapping, paddling or prolonged maintenance of students in painful positions' or anything else causing 'bodily harm.'

- ↑ Cohen, Adam (1 October 2012). "Why Is Paddling Still Allowed in Schools?" Time (New York).

- ↑ Star-Ledger Editorial Board (18 February 2011). "Time to eliminate corporal punishment in classrooms". nj.com.

- ↑ The Ohio ban was signed into law by then-Governor Ted Strickland on 17 July 2009, and enforcement of the ban began on 15 October 2009. "Ohio Bans School Corporal Punishment" Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Center for Effective Discipline, 23 July 2009.

- ↑ (banned by administrative rule R277-608)"States Banning Corporal Punishment", Center for Effective Discipline.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Purtell, Kelly M; Holas, Igor. Corporal punishment in U.S. public schools : legal precedents, current practices, and future policy. Cham. ISBN 9783319148182. OCLC 900942715.

- ↑ Pate, Matthew and Gould, Laurie. Corporal Punishment Around the World. ABC-CLIO, 2012

- ↑ Anderson, Melinda (15 December 2015). "Where Teachers Are Still Allowed to Spank Students". The Atlantic.

- 1 2 Sparks, Sarah and Harwin, Alex. "Corporal Punishment Use Found in Schools in 21 States." Education Week," August 23, 2016.

- ↑ Human Right Watch (2008). A Violent Education Corporal Punishment of Children in US Public Schools. https://www.aclu.org/files/pdfs/humanrights/aviolenteducation_report.pdf

- ↑ Shaw, S. R., & Braden, J. P. (1990). Race and gender bias in the administration of corporal punishment. School Psychology Review, 19(3), 378-383.

- ↑ Czumbil, M. R., & Hyman, I. A. (1997). What happens when corporal punishment is legal? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 309–315. doi:10.1177/088626097012002010.

- ↑ "Corporal Punishment in Schools and Its Effect on Academic Success". Human Rights Watch, American Civil Liberties Union. 15 April 2010. Retrieved November 2015. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - 1 2 Gregory, James F. (1995). "The Crime of Punishment: Racial and Gender Disparities in the use of Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools". The Journal of Negro Education. 64 (4): 454–462. doi:10.2307/2967267. JSTOR 2967267.

- ↑ Skiba, Russell J.; Michael, Robert S.; Nardo, Abra Carroll; Peterson, Reece L. (2002-12-01). "The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Punishment". The Urban Review. 34 (4): 317–342. doi:10.1023/a:1021320817372. ISSN 0042-0972.

- ↑ Gershoff, E. T. (2008). Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

- ↑ McFadden, Anna C.; Marsh, George E.; Price, Barrie Jo; Hwang, Yunhan (1992-12-01). "A study of race and gender bias in the punishment of handicapped school children". The Urban Review. 24 (4): 239–251. doi:10.1007/BF01108358. ISSN 0042-0972.

- ↑ North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. (2013). Consolidated Data Report, 2011-2012. State Board of Education, Public Schools of North Carolina.

- ↑ Force, American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task. "Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: An evidentiary review and recommendations". American Psychologist. 63 (9): 852–862. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.63.9.852.

- ↑ Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (1990). P.L. 101–476.

- ↑ "Corporal Punishment in Schools and Its Effect on Academic Success". Human Rights Watch, American Civil Liberties Union. 15 April 2010. Retrieved November 201

- ↑ "Chair McCarthy Statement at Subcommittee Hearing on 'Corporal Punishment in Schools and Its Effect on Academic Success'" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF). U.S. House of Representatives Education & Labor Committee. 15 April 2010. Retrieved November 2015

- ↑ Hyman, Irwin A. "Corporal punishment, psychological maltreatment, violence, and punitiveness in America: Research, advocacy, and public policy". Applied and Preventive Psychology. 4 (2): 113–130. doi:10.1016/s0962-1849(05)80084-8.

- ↑ Ogando Portela, Maria José; Pells, Kirrily (2015). C orporal Punishment in Schools - Longitudinal Evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Viet Nam, Innocenti Discussion PapersUNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti, Florence.

- ↑ Schmitt, Michael T.; Branscombe, Nyla R.; Postmes, Tom; Garcia, Amber. "The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 140 (4): 921–948. doi:10.1037/a0035754.

- ↑ Smalls C., White, R., Chavous, T., & Sellers, R. (2007). Racial ideological beliefs and racial discrimination experiences as predictors of academic engagement among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 33, 299-330. doi:10.1177/0095798407302541

- 1 2 Center for Effective Discipline (2010), Paddling Versus ACT Scores - A Retrospective Analysis, Ohio: Center for Effective Discipline.

- ↑ Elizabeth T. Gershoff, More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children, 73 Law and Contemporary Problems 31-56 (Spring 2010)

- ↑ Little, Steven G.; Akin-Little, Angeleque (2008-03-01). "Psychology's contributions to classroom management". Psychology in the Schools. 45 (3): 227–234. doi:10.1002/pits.20293. ISSN 1520-6807.

- ↑ Vagins, Deborah J. (3 July 2010). "An Arcane, Destructive — and Still Legal — Practice." The Huffington Post.

- ↑ McCarthy, Carolyn (2010). Congresswoman Carolyn McCarthy Introduces Legislation to End Corporal Punishment in Schools. 29 June 2010.

- ↑ H.R. 5628, 111th Congress, 2d Session

- ↑ H.R. 1522, 102d Congress, 1st Session.

- ↑ H.R. 160, 115th Congress. Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools Act of 2017

- ↑ "Corporal punishment" Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. National Association of Secondary School Principals. February 2009.

- ↑ " Clinical growth charts: Set 2 summary file." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2000).

- ↑ Anne-Marie Iselin, Research on School Suspension, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University(Spring 2010)

External links

- Office for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Education

- A Violent Education: Corporal Punishment of Children in U.S. Public Schools, American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch