Saterland Frisian language

| Saterland Frisian | |

|---|---|

| Seeltersk | |

| Native to | Germany |

| Region | Saterland |

Native speakers | 1,000 (2007)[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in |

Germany |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

stq |

| Glottolog |

sate1242[2] |

| Linguasphere |

52-ACA-ca[3] |

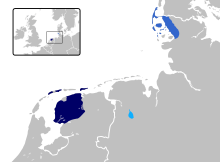

Present-day distribution of the Frisian languages in Europe:

Saterland Frisian | |

Saterland Frisian, also known as Sater Frisian or Saterlandic (Seeltersk), is the last living dialect of the East Frisian language. It is closely related to the other Frisian languages: North Frisian, spoken in Germany as well, and West Frisian, which is spoken in a part of the Netherlands.

Old East Frisian and its decline

Old East Frisian used to be spoken in East Frisia (Ostfriesland), the region between the Dutch river Lauwers and the German river Weser. The area also included two small districts on the east bank of the Weser, the lands of Wursten and Würden. The Old East Frisian language could be divided into two dialect groups: Weser Frisian to the east, and Ems Frisian to the west. From 1500 onwards, Old East Frisian slowly had to give way in the face of the severe pressure put on it by the surrounding Low German dialects, and nowadays it is all but extinct.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, Ems Frisian had almost completely died out. Weser Frisian, for the most part, did not last much longer, and held on only until 1700, although there are records of it still being spoken in the land of Wursten, to the east of the river Weser, in 1723. It held out the longest on the island of Wangerooge, where the very last Weser Frisian speaker died in 1953. Today, the Old East Frisian language is no longer spoken within the historical borders of East Frisia; however, a large number of the inhabitants of that region still consider themselves Frisians, referring to their dialect of Low German as Freesk. In this dialect, referred to in German as Ostfriesisch, the Frisian substratum is still evident, despite heavy Germanisation.

Sater Frisian

The last remaining living remnant of Old East Frisian is an Ems Frisian dialect called Sater Frisian or Saterlandic (its native name being Seeltersk), which is spoken in the Saterland area in the former State of Oldenburg, to the south of East Frisia proper. Saterland (Seelterlound in the local language), which is believed to have been colonised by Frisians from East Frisia in the eleventh century, was for a long time surrounded by impassable moors. This, together with the fact that Sater Frisian always had a status superior to Low German among the inhabitants of the area, accounts for the preservation of the language throughout the centuries.

Another important factor was that after the Thirty Years' War, Saterland became part of the bishopric of Münster. As a consequence, it was brought back under control of the Catholic Church, resulting in social separation from Protestant East Frisia since about 1630. Catholic religious law demanded a confirmation of the non Catholic partner and this condition prevented contact, so marriages of Saterlanders were seldomly contracted with East Frisians for some ages.

Speakers

Today, estimates of the number of speakers vary slightly. Saterland Frisian is spoken by about 2,250 people, out of a total population in Saterland of some 10,000; an estimated 2,000 people (of whom, slightly fewer than half are native speakers) speak the language well.[4] The great majority of native speakers belong to the older generation; Saterland Frisian is thus a seriously endangered language. It might, however, no longer be moribund, as several reports suggest that the number of speakers is rising among the younger generation, some of whom raise their children in Saterlandic.

Dialects

There are three fully mutually intelligible dialects, corresponding to the three main villages of the municipality of Saterland: Ramsloh (Saterlandic: Roomelse), Scharrel (Schäddel), and Strücklingen (Strukelje). The Ramsloh dialect now somewhat enjoys a status as a standard language, since a grammar and a word list were based on it.

Status

The German government has not committed significant resources to the preservation of Sater Frisian. Most of the work to secure the endurance of this language is therefore done by the Seelter Buund ("Saterlandic Alliance"). Along with North Frisian and five other languages, Sater Frisian was included in Part III of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages by Germany in 1998. Since about 1800, Sater Frisian has attracted the interest of a growing number of linguists. During the last century, a small literature developed in it. Also the New Testament of the Bible has been translated into Sater Frisian.

Phonology

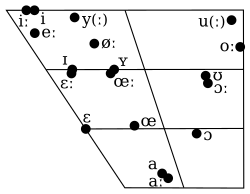

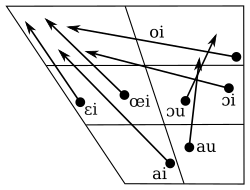

The phonology of Saterland Frisian is regarded as very conservative linguistically, as the entire East Frisian language group was conservative with regards to Old Frisian.[5] The following tables are based on studies by Marron C. Fort.[6]

Vowels

Monophthongs

The consonant /r/ is often realised as a vowel [ɐ̯ ~ ɐ] in the syllable coda.

Short vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | fat (fat) |

| ä | /ɛ/ | Sät (a while) |

| e | /ə/ | ze (they) |

| i | /ɪ/ | Lid (limb) |

| o | /ɔ/ | Dot (toddler) |

| ö | /œ/ | bölkje (to shout) |

| u | /ʊ/ | Buk (book) |

| ü | /ʏ/ | Djüpte (depth) |

Semi-long vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ie | /iˑ/ | Piene (pain) |

| uu | /uˑ/ | kuut (short) |

Long vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| aa | /aː/ | Paad (path) |

| ää | /ɛː/ | tään (thin) |

| ee | /eː/ | Dee (dough) |

| íe | /iː/ | Wíek (week) |

| oa | /ɔː/ | doalje (to calm) |

| oo | /oː/ | Roop (rope) |

| öä | /œː/ | Göäte (gutter) |

| üü | /yː/ | Düwel (devil) |

| úu | /uː/ | Múus (mouse) |

Diphthongs

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ai | /aːi/ | Bail (bail) |

| au | /aːu/ | Dau (dew) |

| ääu | /ɛːu/ | sääuwen (self) |

| äi | /ɛɪ/ | wäit (wet) |

| äu | /ɛu/ | häuw (hit, thrust) |

| eeu | /eːu/ | skeeuw (skew) |

| ieu | /iˑu/ | Grieuw (advantage) |

| íeu | /iːu/ | íeuwen (even, plain) |

| iu | /ɪu/ | Kiuwe (chin) |

| oai | /ɔːɪ/ | toai (tough) |

| oi | /ɔy/ | floitje (to pipe) |

| ooi | /oːɪ/ | swooije (to swing) |

| ou | /oːu/ | Bloud (blood) |

| öi | /œːi/ | Böije (gust of wind) |

| uui | /uːɪ/ | truuije (to threaten) |

| üüi | /yːi/ | Sküüi (gravy) |

Consonants

Plosives

Today, voiced plosives in the syllable coda are usually terminally devoiced. Older speakers and a few others may use voiced codas.

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | /p/ | Pik (pitch) | |

| t | /t/ | Toom (bridle) | |

| k | /k/ | koold (cold) | |

| b | /b/ | Babe (father) | Occasionally voiced in syllable coda |

| d | /d/ | Dai (day) | May be voiced in syllable coda by older speakers |

| g | /ɡ/ | Gäize (goose) | A realization especially used by younger speakers instead of [ɣ]. |

Fricatives

| Grapheme | Phoneme(s) | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| g | /ɣ, x/ | Gäize (goose), Ploug (plough) | Voiced velar fricative, unvoiced in the syllable coda and before an unvoiced consonant. Younger speakers show a tendency towards using the plosive [ɡ] instead of [ɣ], as in German, but that development has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| f | /f, v/ | Fjúur (fire) | Realised voicedly by a suffix: ljoof - ljowe (dear - love) |

| w | /v/ | Woater (water) | Normally a voiced labio-dental fricative like in German, after u it is however realised as bilabial semi-vowel (see below). |

| v | /v, f/ | iek skräive (I scream) | Realised voicelessly before voiceless consonants: du skräifst (you scream) |

| s | /s, z/ | säike (to seek), zuuzje (to sough) | Voiced [z] in the syllable onset is unusual for Frisian dialects and also rare in Saterlandic. There is no known minimal pair s - z so /z/ is probably not a phoneme. Younger speakers tend to use [ʃ] more, for the combination of /s/ + another consonant: in fräisk (Frisian) not [frɛɪsk] but [fʀɛɪʃk]. That development, however, has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| ch | /x/ | truch (through) | Only in syllable nucleus and coda. |

| h | /h/ | hoopje (to hope) | Only in onset. |

Other consonants

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| m | /m/ | Moud (courage) | |

| n | /n/ | näi (new) | |

| ng | /ŋ/ | sjunge (to sing) | |

| j | /j/ | Jader (udder) | |

| l | /l/ | Lound (land) | |

| r | /r/, [r, ʀ, ɐ̯, ɐ] | Roage (rye) | Traditionally, a rolled or simple alveolar [r] in onsets and between vowels. After vowels or in codas, it becomes [ɐ]. Younger speakers tend to use a uvular [ʀ] instead. That development, however, has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| w | /v/, [w] | Kiuwe (chin) | As in English, it is realised as a bilabial semivowel only after u. |

Morphology

Personal pronouns

The subject pronouns of Saterland Frisian are as follows:[7]

| singular | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| first person | iek | wie | |

| second person | du | jie | |

| third person | masculine | hie, er | jo, ze (unstr.) |

| feminine | ju, ze (unstr.) | ||

| neuter | dät, et, t | ||

The numbers 1-10 in Saterland Frisian are as follows:[8]

| Saterland Frisian | English |

|---|---|

| aan (m.)

een (f., n.) |

one |

| twäin (m.)

two (f., n.) |

two |

| träi (m.)

trjo (f., n.) |

three |

| fjauer | four |

| fieuw | five |

| säks | six |

| sogen | seven |

| oachte | eight |

| njúgen | nine |

| tjoon | ten |

Numbers one through three in Saterland Frisian vary in form based on the gender of the noun they occur with.[8] In the table, "m." stands for masculine, "f." for feminine, and "n." for neuter.

For the purposes of comparison, here is a table with numbers 1-10 in 4 West Germanic languages:

| Saterland Frisian | Low German | German | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| aan (m.)

een (f., n.) |

een | eins | one |

| twäin (m.)

two (f., n.) |

twee | zwei | two |

| träi (m.)

trjo (f., n.) |

dree | drei | three |

| fjauer | veer | vier | four |

| fieuw | fief | fünf | five |

| säks | söss | sechs | six |

| sogen | söben | sieben | seven |

| oachte | acht | acht | eight |

| njúgen | negen | neun | nine |

| tjoon | teihn | zehn | ten |

Sample text

In the media

Newspaper

Nordwest-Zeitung, a German-language regional daily newspaper based in Oldenburg, Germany, publishes occasional articles in Saterland Frisian. The articles are also made available on the newspaper's Internet page, under the headline Seeltersk.

Radio

As of 2004, the regional radio station Ems-Vechte-Welle broadcasts a 2-hour program in Saterland Frisian and Low German entitled Middeeges. The program is aired every other Sunday from 11:00am to 1:00pm. The first hour of the program is usually reserved for Saterland Frisian. The program usually consists of interviews about local issues between music. The station can be streamed live though the station's Internet page.

Current revitalization efforts

Children's books in Saterlandic are few, compared to those in German. Margaretha (Gretchen) Grosser, a retired member of the community of Saterland, has translated many children's books from German into Saterlandic. A full list of the books and the time of their publication can be seen on the German Wikipedia page of Margaretha Grosser.

Recent efforts to revitalize Saterlandic include the creation of an app called "Kleine Saterfriesen" (Little Sater Frisians) on Google Play. According to the app's description, it aims at making the language fun for children to learn teaches them Saterlandic vocabulary in many different domains (the supermarket, the farm, the church). There have been 100-500 downloads of the app since its release in December 2016, according to statistics on Google Play.

Further reading

- Fort, Marron C. (1980): Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

- Kramer, Pyt (1982): Kute Seelter Sproakleere - Kurze Grammatik des Saterfriesischen. Rhauderfehn: Ostendorp.

- Peters, Jörg (2017), "Saterland Frisian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, doi:10.1017/S0025100317000226

- Stellmacher, Dieter (1998): Das Saterland und das Saterländische. Oldenburg.

See also

| Saterland Frisian edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

References

- ↑ Saterland Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Saterfriesisch". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "s" (PDF). The Linguasphere Register. p. 252. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ A number of 6,370 speakers is cited by Fort, Marron C., "Das Saterfriesische", in Munske (2001), p. 410. A 1995 poll counted 2,225 speakers: Stellmacher, Dieter (1995). Das Saterland und das Saterländische (in German). Florian Isensee GmbH. ISBN 978-3-89598-567-6. Ethnologue refers to a monolingual population of 5,000, but this number originally was not of speakers but of persons who counted themselves ethnically Saterland Frisian.

- ↑ Versloot, Arjen: "Grundzüge Ostfriesischer Sprachgeschichte", in Munske (2001).

- ↑ Fort, Marron C., "Das Saterfriesische", in Munske (2001), pp. 411–412. Fort, Marron C. (1980). Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch. Hamburg. pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Howe, Stephen (1996). The Personal Pronouns in the Germanic Languages (1 ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 192. ISBN 9783110819205. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- 1 2 Munske, Horst (2001). Handbuch des Friesischen. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. p. 417. ISBN 3-484-73048-X.

External links

- On-line course in English

- Saterland Frisian Wikipedia (Saterland Frisian)

- Dictionary Saterfrisian-German (according to P. Kramer, Seelter Woudebouk, Ljouwert 1961; spelling modernised).

- Vocabulary German-Saterfrisian