Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom

| Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom | |

|---|---|

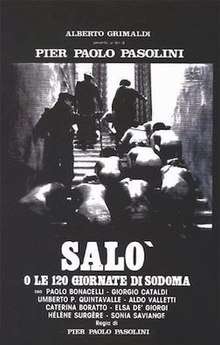

Original Italian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Pier Paolo Pasolini |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

The 120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Edited by | Nino Baragli |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[1] |

| Country | |

| Language |

Italian French German |

| Box office | SEK 1,786,578 |

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Italian: Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma), titled Pasolini's 120 Days of Sodom on English-language prints[3] and commonly referred to as simply Salò (Italian: [saˈlɔ]), is a 1975 Italian-French horror art film[lower-alpha 1] directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. The film is a loose adaptation of the book The 120 Days of Sodom by the Marquis de Sade reset during WWII. The film focuses on four wealthy, corrupt Italian libertines, during WWII in the time of the fascist Republic of Salò (1943–1945). The libertines kidnap eighteen teenagers and subject them to four months of extreme violence, murder, sadism and sexual and mental torture. The film explores the themes of political corruption, murder, abuse of power, sadism, perversion, sexuality and fascism. The story is in four segments, inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy: the Anteinferno, the Circle of Manias, the Circle of Excrement, and the Circle of Blood. The film also contains frequent references to and several discussions of Friedrich Nietzsche's 1887 book On the Genealogy of Morality, Ezra Pound's poem The Cantos and Marcel Proust's novel sequence In Search of Lost Time.

The film premiered at the Paris Film Festival on 23 November 1975, three weeks after Pasolini was murdered in Rome. It had a brief theatrical run in Italy before being banned in January 1976 and was released in the United States the following year on 3 October 1977. Because it depicts youths subjected to intensely graphic violence, relentless sadism, sexual deviance and brutal murder, the film was extremely controversial upon its release and has remained banned in several countries into the 21st century.

The confluence of thematic content in the film—ranging from the political and socio-historical, to psychological and sexual—has led to much critical discussion of the film. It has been both praised and decried by various film historians and critics and was named the 65th scariest film ever made by the Chicago Film Critics Association in 2006.[6] It is also the subject of an entry in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986).[7]

Plot

The film is separated into four segments with intertitles, based on Dante's Divine Comedy:[8]

Anteinferno

In 1944 in the Republic of Salò, the Fascist-occupied portion of Italy, four wealthy men of power, the Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate and the President, agree to marry each other's daughters as the first step in a debauched ritual. They recruit four teenage boys to act as guards (dressed with uniforms of Decima Flottiglia MAS) and four young soldiers (called "studs", "cockmongers" or "fuckers"), who are chosen because of their large penises. They then kidnap nine young men and nine young women and take them to a palace near Marzabotto.

Circle of Manias / Girone delle Manie

Accompanying the libertines at the palace are four middle-aged prostitutes, also collaborators, whose job it is to orchestrate debauched interludes for the men, who sadistically exploit their victims. During the many days at the palace, the four men devise increasingly abhorrent tortures and humiliations for their own pleasure. During breakfast, the daughters enter the dining hall naked to serve food. One of the studs trips and rapes a daughter in front of the crowd, which laughs at her cries of pain. Intrigued, the President moons several slaves before prompting the stud to perform anal sex on him and the Duke sings 'Sul Ponte di perati'. Signora Vaccari uses a mannequin to demonstrate to the young men and women how to properly masturbate a penis and one of the girls tries to escape, only to have her throat cut. Signora Vaccari continues with her story. Two victims, Sergio and Renata, are forced to marry. The ceremony is interrupted when the Duke fondles several victims and prostitutes. At the end, Sergio and Renata are forced to fondle each other and the men rape them to stop them from having sex with each other. During this, the Magistrate engages with the Duke in three-way intercourse.

Another day, the victims are forced to act like dogs. When one of the victims, Lamberto, refuses, the Magistrate whips him and tortures the President's daughter by tricking her into eating food containing nails.

Circle of Shit / Girone della Merda

Signora Maggi relates her troubled childhood and her coprophilia. As she tells her story, the President notices that one of the studs has an erection and fondles him; another stud uses a female victim's hand to masturbate himself. She also explains how she killed her mother over a dispute about her prostitution and Renata cries, remembering the murder of her own mother. The Duke, sexually excited at the sound of her cries, begins verbally abusing her. The Duke orders the guards and studs to undress her. During this, she begs God for death and the Duke punishes her by defecating and forcing her to eat his feces. The President leaves to masturbate. Later, the other victims are presented with a meal of human feces. During a search for the victim with the most beautiful buttocks, Franco is picked and promised death in the future.

Circle of Blood / Girone del Sangue

Later, there is a Black Mass-like wedding between the studs and the men of power. The men angrily order the children to laugh, but they are too grief-stricken to do so. The Pianist and Signora Vaccari tell jokes to make the victims laugh. The wedding ceremony ensues with each man of power exchanging rings with a stud. After the wedding, the Bishop consummates the marriage and receives anal sex from his stud. The Bishop then leaves to examine the captives in their rooms, where they start systematically betraying each other: Claudio reveals that Graziella is hiding a photograph, Graziella reveals that Eva and Antiniska are having a secret sexual affair and Ezio, a collaborator and the black servant are shot dead after being found having sex, but not before Ezio makes a defiant Socialist salute. Victim Umberto Chessari is appointed to replace Ezio.

Toward the end, the remaining victims are called out to determine which of them will be punished. Graziella is spared due to her betrayal of Eva and Rino is spared due to his submissive relationship with the Duke. Those who are called are given a blue ribbon and sentenced to a painful death. The victims huddle together and cry and pray in the bathroom. They are then raped, tortured and murdered through methods such as branding, hanging, scalping, burning and having their tongues and eyes cut out, as each libertine takes his turn to watch as a voyeur. The soldiers shake hands and bid each other farewell and the Pianist commits suicide due to her grief, leaping from a window.

The film's final shot is of two young soldiers, who had witnessed and collaborated in all the atrocities, dancing a simple waltz together; one asks the name of the other's girlfriend back at home.

Cast

Masters

- Paolo Bonacelli (voiced by Giancarlo Vigorelli) as The Duke; tall, strongly built, bearded, chauvinistic and very sadistic; enjoys tormenting female victims with verbal abuse and degrading them, his favorite victims being Renata and Fatimah. Highly sexually potent. Shows loving feelings for the male victim Rino and allows him to live at the end.

- Giorgio Cataldi (voiced by Giorgio Caproni) as The Bishop; the Duke's extremely sadistic brother. Writes down several victims' names for punishment. May have a soft spot for Graziella.

- Umberto Paolo Quintavalle (voiced by Aurelio Roncaglia) as The Magistrate; mustachioed sadomasochist; fit and balding; enjoys bullying the victims, yet shows joy from being sodomized. Very strict.

- Aldo Valletti (voiced by Marco Bellocchio) as The President; scrawny, weak and crude. He enjoys dark and punning humor and painful penetration to himself and others. He is passionate about anal sex even when having sex with women and girls, refusing to have vaginal intercourse with them.

Storytellers, Middle-age prostitutes

- Caterina Boratto as Signora Castelli; a prideful, cruel prostitute who jokes about horrible instances. Tells stories during the Circle of Blood.

- Elsa De Giorgi as Signora Maggi; a coprophiliac who finds no shame in defecating in front of others. Committed matricide for a nobleman. Tells stories during the Circle of Shit.

- Hélène Surgère (voiced by Laura Betti) as Signora Vaccari; lively and polite, she was molested as a very young child, but enjoyed it. Tells stories during the Circle of Manias.

- Sonia Saviange as The Pianist; soft-spoken, she plays continuously during the day, but is secretly very distressed at the actions around her. Commits suicide during the final day.

Soldiers or Studs

- Rinaldo Missaglia as Stud; like the Duke is strongly built, chauvinistic and very sadistic; enjoys tormenting female victims with verbal abuse and degrading them.

- Giuseppe Patruno as Stud; the calmest of the studs.

- Guido Galletti as Stud; with bisexual tendencies and has relations with the Bishop.

- Efisio Etzi as Stud; most cruel and degenerate. Mistreats victims, especially women.

Collaborators

- Claudio Troccoli as The Collaborator; a teenager but cruel guard and as depraved as the Masters.

- Fabrizio Menichini as The Collaborator; another teenager and quiet soldier recruited at the beginning of the film.

- Maurizio Valaguzza as Bruno, The Collaborator; teenager cruel like Claudio who befriends him.

- Ezio Manni as The Collaborator; a quiet guard who falls in love with the Slave Girl. Like the Pianist is secretly very distressed at the actions around him. He is aware of his fate when he is found out and is shot to death while holding his fist in the air in a Socialist salute.

Servants

- Inès Pellegrini as The Slave Girl, a black slave in love with the Collaborator. Disobeyed orders by engaging in intercourse without the presence of the Masters. Is shot after the Collaborator.

Male victims

- Sergio Fascetti – Forced to marry, but kept from actual intercourse. He is then raped by the President. In the end, he is branded and killed.

- Bruno Musso – Carlo Porro; an outspoken boy who shows a foul mouth even to the Masters. One of the Magistrate's favorite victims of bullying. In the end, he is killed by having his left eye gouged out.

- Antonio Orlando – Tonino; killed by having his penis burned off.

- Claudio Cicchetti – Confesses to the Bishop about Graziella's photograph, leading to a chain of revealed secrets. Killed in the end.

- Franco Merli – Prideful and youthful. Tricked into his position with a promise of sex with an attractive girl. Said to have the most beautiful buttocks. Nearly killed midway through the film, but spared on a promise of a worse future death. He is killed at the end by having his tongue cut off.

- Umberto Chessari – Selected to replace Ezio as Collaborator after Ezio is shot to death.

- Lamberto Book – Lamberto Gobbi; he refuses to eat like dogs and is whipped by the Magistrate. Also killed in the end.

- Gaspare di Jenno – Rino; a slightly masochistic homosexual and the Duke's favorite. He has sexual feelings for the Duke and is therefore the only victim who is not tortured during his time at the palace. In the end, he is spared death because of his submission.

Female victims

- Giuliana Melis – Admired by the President because of her buttocks. Raped and killed at the end.

- Faridah Malik – Fatimah; a common victim of both the Duke's sexism and the Magistrate's bullying. In the end, she is scalped.

- Graziella Aniceto – Graziella finds her time at the Palace unbearable and is calmed by Dorit and Eva, the latter of which she betrays. She is left alive at the film's end along with Rino.

- Renata Moar – Renata; a God-fearing and especially wide-eyed innocent. Forced into the palace just not long after witnessing the death of her mother. She is forced to marry Sergio before being raped by the Duke. When she hears that they killed her mother, she begs God for death. The Duke enjoys tormenting her and at one point forces her to consume his feces. She is killed at the end by having her breasts burned.

- Benedetta Gaetani – Although she is not present in the blue ribbon ceremony, Benedetta is also killed in the massacre.

- Olga Andreis – Eva; a soft-spoken girl who is friends with Graziella and in love with Antiniska. Her fate is unknown.

- Dorit Henke – Beautiful and rebellious; the most undisciplined of the girls. Her fate is unknown.

- Antiniska Nemour – In a lesbian relationship with Eva. Her fate is unknown.

Daughters

- Tatiana Mogilansky - Magistrate's daughter married with the President. Blond and beautiful, but victim of the bullying of the collaborationists and the studs. Raped and killed at the end.

- Susanna Radaelli - President's daughter married with the Duke. Victim of the collaborationists and the Magistrate. Raped and killed at the end by hanging.

- Giuliana Orlandi - Duke's minor daughter married with the Bishop. Killed at the end.

- Liana Acquaviva - Duke's major daughter married with the Magistrate. Raped by one of the studs and killed in the end; in a deleted scene in an electric chair.

Production

Conception

Pasolini's writing collaborator Sergio Citti had originally been attached to direct the film version of the Marquis de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom.[9] During the creation of the first drafts of the script, Pasolini appealed to several of his usual collaborators, among them Citti, Claudio Masenza, Antonio Troisi and specially Pupi Avati.[10]

While collaborating with Citti on the script, Pasolini was compelled to transpose the setting of Salò from 18th-century France (as depicted in de Sade's original book) to the last days of Benito Mussolini's regime in the Republic of Salò in the spring of 1944.[11] Salò is a toponymical metonymy for the Italian Social Republic (RSI) (because Mussolini ruled from this northern town rather than from Rome), which was a puppet state of Nazi Germany.[12] While writing the script, it was decided between Citti and Pasolini that the latter would direct the project, as Citti had planned to write a separate project after completing Salò.[13] Pasolini noted his main contribution to Citti's original screenplay as being its "Dante-esque structure,"[14] which Pasolini felt had been de Sade's original intention with the source material.[15]

In the film almost no background is given on the tortured subjects and for the most part they almost never speak.[16] Pasolini's depiction of the victims in such a manner was intended to demonstrate the physical body "as a commodity...the annulment of the personality of the Other."[17] Specifically, Pasolini intended to depict what he described as an "anarchy of power,"[18] in which sex acts and physical abuse functioned as metaphor for the relationship between power and its subjects.[19] Aside from this theme, Pasolini also described the film as being about the "nonexistence of history" as it is seen from Western culture and Marxism.[20]

Trilogy of death

In contrast to his "Trilogy of Life" (Il Decameron, I racconti di Canterbury and Il fiore delle Mille e una notte), Pasolini initially planned The 120 days of Sodom and Salò as separate stories, but noting similarity between both concepts and based on their experiences in the Republic of Salò conceived the idea of Salò or the 120 days of Sodom. Pasolini established that the violence scenes in Salò were symbolic and reducing the romanticism of his previous films, although knowing that once the film was premiered would be considered as damned. As a continuation, Pasolini planned to bring to the cinema the life of the murderer and pederast Gilles de Rais, but after his death, the idea was aborted.

Casting

Initially Ninetto Davoli was chosen to play Claudio, a young collaborationist, but due to legal problems he had to decline, the role being replaced by Claudio Troccoli, a young man who had a similarity to Davoli in his first films. Pupi Avati, being the writer, is not officially accredited due also to legal problems. Most of the actors of the cast, although they were natural actors, many of them were models that did not have modesty to show their naked bodies and most of them retaining their original name. Franco Merli was considered like a prototype of the Pasolinian boy. Ezio Manni remembers during filming: "The same with Franco Merli, the boy chosen for the seat more beautiful. When to reward the link the gun to his head, he had a rebellious snap, could not withstand that gesture. Then, there, too, he came the assistant director and if it is embraced."[21]

Franco Citti was going to play one of the soldiers' studs, but he did not appear. Laura Betti was also going to play Signora Vaccari, but also because of legal problems and her commitments to the movie "Novecento" declined the role, even though she doubled the voice of Hélène Surgère.

Umberto Paolo Quintavalle (the Magistrate) was a writer, he knew Pasolini working on the newspaper Corriere della Sera. He was chosen for the role because he had all "the characteristics of a decadent intellectual."[22]

Aldo Valletti (the President) was a friend of Pasolini from the time of Accattone. Giorgio Cataldi (the bishop) another friend of Pasolini, was a clothes seller in Rome.

Paolo Bonacelli (El Duque) had participated in several small Italian productions of the 1950s and 1960s.

Filming

Several outdoor scenes were filmed in Villa Aldini,[23] a neoclassical building on the hills of Bologna. The interiors were shot in Villa Sorra near Castelfranco Emilia.[24] The noble hall of the building and the courtyard were filmed in the Cinecittà studios. The town on the Reno replaces the fictional location in Marzabotto.

The shooting, carried out mainly in the sixteenth-century Villa Gonzaga-Zani in Villimpenta in the spring of 1975, was difficult and involved scenes of homophilia, coprophagia and sadomasochism. The acts of torture in the courtyard caused some of the actors to suffer abrasions and burns.[25] Actress Hélène Surgère described the film shoot as "unusual", with nearly forty actors being on set at any given time, and Pasolini shooting "enormous" amounts of footage.[26] She also noted the mood on the set as "paradoxically jovial and immature" in spite of the content.[27] In-between working, the cast shared large meals of risotto and also had football games played against the crew of Bernardo Bertolucci's Novecento, which was being filmed nearby.[28] It also marked the reconciliation between the then 34-year-old Bertolucci and his old mentor after several disagreements following Pasolini's criticism of Last Tango in Paris (1972) and his failure to defend it from drastic censorship measures.[29]

During the making of the film, some reels were stolen and the thieves demanded a ransom for their return. They reshot the scenes, using doubles: the same scenes, but from a different angle. At the trial for Pasolini's murder, it was hypothesized that Pasolini was told the film reels were discovered in Ostia Lido. He was led there by Pelosi, the accused, and fell victim to an ambush, where he died.[30]

Post-production

Musical score

The original music corresponds to Ennio Morricone interpreted at the piano by Arnaldo Graziosi. Other non-original music was Carl Orff's Carmina Burana in Veris leta facies at the nearly end of the film during Circle of Blood. Other music was several Frédéric Chopin's pieces Preludes Op.28 nº 17 and nº4 and Valses Op. 34 nº 2 in La minor).

Alternate endings

It seems that Pasolini was undecided on what type of conclusion the film should have, to the point of having conceived and shot four different endings: the first was a shot of a red flag in the wind with the words "Love You", but it was abandoned by the director because he thought it "too pompous" and "prone to the ethics of psychedelic youth", which he detested.[31] The second showed all the actors in the film, other than the four gentlemen, the director and his troupe perform a wild dance in a room of the villa furnished with red flags and the scene was filmed with the purpose of using it as a background scene during the credits, but was discarded because it appeared, in the eyes of Pasolini, chaotic and unsatisfactory.[31] Another final scene, discovered years later and which was only in the initial draft of the script, showed, after the torture's end, the four gentlemen walk out of the house and drawing conclusions about the morality of the whole affair.[32] Finally, keeping the idea of dance as the summation of carnage, Pasolini chose to mount the so-called final "Margherita", with the two young soldiers dancing.[31]

Release

Salò premiered at the Paris Film Festival on 23 November 1975, three weeks after Pasolini's death.[33] In Italy, the film was initially rejected for screening by the Italian censorship, but received approval on 23 December 1975.[34] The approval, however, was withdrawn three weeks after the film's Italian release in January 1976 and it was formally banned.[34][35] Worldwide distribution for the film was supplied by United Artists.[36] In the United States, however, the film was given a limited release via Zebra Releasing Corporation on 3 October 1977.[37]

Censorship

Pasolini on the film's depiction of sex, 1975.[19]

Salò has been banned in several countries, because of its graphic portrayals of rape, torture and murder—mainly of people thought to be younger than eighteen years of age. The film remains banned in several countries and sparked numerous debates among critics and censors about whether or not it constituted pornography due to its nudity and graphic depiction of sex acts.[38]

The film was rejected by the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) in January 1976. It was first screened at the Old Compton Street cinema club in Soho, London in 1977, in an uncut form and without certification from BBFC secretary James Ferman; the premises were raided by the Metropolitan Police after a few days. A cut version prepared under Ferman's supervision, again without formal certification, was subsequently screened under cinema club conditions for some years. In 2000, in an uncut form, the film was finally passed for theatrical and video distribution in the United Kingdom.[39]

The film was not banned in the United States and received a limited release in October 1977; it was, however, banned in Ontario, Canada.[40] In 1994, an undercover policeman in Cincinnati, Ohio, rented the film from a local gay bookstore and then arrested the owners for "pandering". A large group of artists, including Martin Scorsese and Alec Baldwin, and scholars signed a legal brief arguing the film's artistic merit; the Ohio state court dismissed the case because the police violated the owners' Fourth Amendment rights, without reaching the question of whether the film was obscene.[41]

It was banned in Australia in 1976 for reasons of indecency.[42] After a 17-year-long ban, the Australian Classification Board passed the film with a R-18+ (for 18 and older only) uncut for theatrical release in July 1993. However, the Australian Classification Review Board overturned this decision in February 1998 and banned the film outright, for "offensive cruelty with high impact, sexual violence and depictions of offensive and revolting fetishes". The film was then pulled from all Australian cinemas. Salò was resubmitted for classification in Australia in 2008, only to be rejected once again.[43] The DVD print was apparently a modified version, causing outrage in the media over censorship and freedom of speech. In 2010, the film was submitted again and passed with an R18+ rating. According to the Australian Classification Board media release, the DVD was passed due to "the inclusion of 176 minutes of additional material which provided a context to the feature film." The media release also stated that "The Classification Board wishes to emphasise that this film is classified R18+ based on the fact that it contains additional material. Screening this film in a cinema without the additional material would constitute a breach of classification laws."[44] The majority opinion of the board stated that the inclusion of additional material on the DVD "facilitates wider consideration of the context of the film which results in the impact being no more than high."[45] This decision came under attack by FamilyVoice Australia (formerly the Festival of Light Australia), the Australian Christian Lobby and Liberal Party of Australia Senator Julian McGauran,[46] who tried to have the ban reinstated, but the Board refused, stating "The film has aged plus there is bonus material that clearly shows it is fiction."[47][48] The film was released on Blu-ray Disc and DVD on 8 September 2010.[49][50]

In New Zealand, the film was originally banned in 1976. The ban was upheld in 1993. In 1997, special permission was granted for the film to be screened uncut at a film festival. In 2001, the DVD was finally passed uncut with an 'R18' rating.[51]

Reception

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports that 71% of 28 surveyed critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating is 6.4/10.[52] Director Michael Haneke named the film his fourth favorite film when he voted for the 2002 Sight and Sound poll; director Catherine Breillat and film critic Joel David also voted for the film.[53] David Cross and Gaspar Noé named it one of their favorite films.[54][55] Rainer Werner Fassbinder also cited it as one of his 10 favorite movies.[56] A 2000 poll of critics conducted by The Village Voice named it the 89th greatest film of the 20th century.[57] Director John Waters said, "Salo is a beautiful film...it uses obscenity in an intelligent way...and it's about the pornography of power."[58]

The film's reputation for pushing boundaries has led some critics to criticize or avoid it; the Time Out film guide, for example, deemed the film a "thoroughly objectionable piece of work," adding that it "offers no insights whatsoever into power, politics, history or sexuality."[59] TV Guide gave the film a mixed review awarding it a score of 2.5/4, stating, "despite moments of undeniably brilliant insight, is nearly unwatchable, extremely disturbing, and often literally nauseous".[60]

Upon the film's release in the United States, Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote, "Salo is, I think, a perfect example of the kind of material that, theoretically, anyway, can be acceptable on paper but becomes so repugnant when visualized on the screen that it further dehumanizes the human spirit, which is supposed to be the artist's concern."[37] In 2011 Roger Ebert wrote that he owned the film since its release on Laserdisc but had not watched it, citing the film's transgressive reputation.[61] In 2011, David Haglund of Slate surveyed five film critics and three of them said that it was required viewing for any serious critic or cinephile. Haglund concluded that he still would not watch the film.[62]

Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader wrote of the film: "Roland Barthes noted that in spite of all its objectionable elements (he pointed out that any film that renders Sade real and fascism unreal is doubly wrong), this film should be defended because it 'refuses to allow us to redeem ourselves.' It's certainly the film in which Pasolini's protest against the modern world finds its most extreme and anguished expression. Very hard to take, but in its own way an essential work."[63]

Home media

The Criterion Collection first released the film in 1993 on LaserDisc, following with a DVD release in 1998.[64] In 2011, The Criterion Collection released a newly restored version on Blu-ray and DVD in conjunction with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a two-disc release with multiple interviews collected on the accompanying second disc.[65]

Critical analysis

Salò has received critical analysis from film scholars, critics and others for its converging depictions of sexual violence and cross-referencing of historical and sociopolitical themes. Commenting on the film's prevalent sexual themes, horror film scholar Stephen Barber writes: "The core of Salò is the anus, and its narrative drive pivots around the act of sodomy. No scene of a sex act has been confirmed in the film until one of the libertines has approached its participants and sodomized the figure committing the act. The filmic material of Salò is one that compacts celluloid and shit, in Pasolini's desire to burst the limits of cinema, via the anally resonant eye of the film lens."[34] Barber also notes that Pasolini's film reduces the extent of the storytelling sequences present in de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom so that they "possess equal status" with the sadistic acts committed by the libertines.[66]

Pasolini scholar Gian Annovi notes in the book Pier Paolo Pasolini: Performing Authorship (2007) that Salò is stylistically and thematically marked by a "link between Duchamp's Dada aesthetics and the perverse dynamics of desire," which, according to Annovi, became artistic points of interest for Pasolini in the early developments of Salò.[67]

Legacy

Salò has earned a reputation amongst some film scholars for being the "sickest film of all time,"[68][69] with some citing it as an early progenitor of the torture porn subgenre, alongside the American film The Last House on the Left (1972).[70] Film scholar Mattias Frey notes that the cross-section between the film's thematic content and graphic visuals has resulted in it being considered both a horror film as well as an art film: "[Films like Salò], which are usually considered by critics as "works" by the "artists"...might be received in practice also by individuals who watch Saw or Hostel or any "popular" or cult horror film."[4] In 2006, the Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 65th scariest film ever made[6] and in 2010, the Toronto International Film Festival placed it at no. 47 on its list of "The Essential 100 films".[71]

In 2008, British opera director David McVicar and Swiss conductor Philippe Jordan have produced a performance of Richard Strauss' 1905 opera Salome based on the film, setting it in a debauched palace in Nazi Germany, for the Royal Opera House in London, with Nadja Michael as Salome, Michaela Schuster as Herodias, Thomas Moser as Herod, Joseph Kaiser as Narraboth, and Michael Volle as Jokanaan. This performance was recorded by Jonathan Haswell and later that year was released on DVD by Opus Arte.[72]

Nikos Nikolaidis' 2005 The Zero Years has been compared to the film.[73] The film is also the subject of the 2001 documentary Salò: Fade to Black written by Mark Kermode and directed by Nigel Algar.[74] An exhibition of photographs by Fabian Cevallos depicting scenes which were edited out of the film was displayed in 2005 in Rome. Italian filmmaker Giuseppe Bertolucci released a documentary in 2006, Pasolini prossimo nostro, based on an interview with Pasolini done on the set of Salò in 1975. The documentary also included photographs taken on the set of the film.

Notes

References

- ↑ "SALÒ, OR THE 120 DAYS OF SODOM (18)". British Board of Film Classification]. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- 1 2 "SALÒ O LE CENTOVENTI GIORNATE DI SODOMA (1975)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ "Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom Blu-ray". DVDBeaver. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- 1 2 Frey, Mattias (2013). "The Ethics of Extreme Cinema". In Choi, Jinhee; Frey, Mattias. Cine-Ethics: Ethical Dimensions of Film Theory, Practice, and Spectatorship. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-136-74596-6.

- ↑ "Shock value". The Guardian. 22 September 2000. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- 1 2 Chicago Film Critics Association (October 2006). "Top 100 Scariest Movies". Filmspotting. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ↑ Campbell, Ramsey (1986). "Salò – The 120 Days of Sodom". In Sullivan, Jack. The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. Penguin. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-670-80902-8.

- ↑ Taskale, Ali Raza (2016). Post-Politics in Context. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-317-28249-5.

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (05:25)

- ↑ Giubilei, Franco (11 February 2015). "Pupi Avati: io che scrissi "Salò", non l'ho mai visto fino in condo". La Stampa Spettacoli (in Italian). Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Wells 2008, p. 127.

- ↑ Annovi 2017, p. 41.

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (05:22)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (05:29)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (05:38)

- ↑ Aaron Kerner (5 May 2011). Film and the Holocaust: New Perspectives on Dramas, Documentaries, and Experimental Films. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-4411-0893-7.

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (07:38)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (07:47)

- 1 2 Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (07:08)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (08:12)

- ↑ Sergio Sciarra (28 February 2007). "Pasolini e gli altri, dall'anti-inferno privato ai gironi di Salò" (PDF). il Riformista.

- ↑ Hart, Kylo-Patrick R., ed. (2009). "Homosexuality and/as Fascism in Italian Cinema". Mediated Deviance and Social Otherness: Interrogating Influential Representations. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-443-80371-7.

- ↑ Guidi, Alessandro; Sassetti, Pierluigi, eds. (2009). L'eredità di Pier Paolo Pasolini (in Italian). Mimesis Edizioni. p. 54. ISBN 978-88-8483-838-4.

- ↑ "Location verificate: Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (1975)". Davinotti (in Italian). 4 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (01:49)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (07:14)

- ↑ Pasolini, Biette & Davoli 2002 (18:14)

- ↑ Gundle & Rinaldi 2007, p. 161.

- ↑ Barber 2010, p. 99.

- ↑ Borgna, Gianni; Veltroni, Walter (18 February 2011). "Chi ha ucciso Pasolini". L'Espresso. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Pier Paolo Pasolini, di Serafino Murri, casa editrice Il Castoro, edizione 2008.

- ↑ Mario Sesti, La fine di Salò, extra del DVD La voce di Pasolini, di Mario Sesti e Matteo Cerami.

- ↑ Moliterno 2009, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 Barber 2010, p. 100.

- ↑ Zampini, Tania (2016). Scala, Carmen, ed. New Trends in Italian Cinema: "New" Neorealism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-443-86787-0.

- ↑ "3 U.S. Films Make N.Y. Festival List". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. 23 August 1977. p. 28 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Canby, Vincent (1 October 1977). "Film Festival: 'Salo' Is Disturbing..." The New York Times. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ Cetti, Robert (2014). Offensive to a Reasonable Adult: Film Censorship and Classification in Australia. Robert Cetti. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-987-24255-6.

- ↑ This paragraph draws heavily on the article "Case Study: Salo Archived 18 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. on the Students' British Board of Film Classification website.

- ↑ Lerner, Loren Ruth (1997). Canadian Film and Video: A Bibliography and Guide to the Literature. University of Toronto Press. p. 802. ISBN 978-0-802-02988-1.

- ↑ "ACLU Arts Censorship Project Newsletter". Theroc.org. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ↑ "Salò". Media Information Australia. Australian Film and Television School. 67–70: 126–7. 1993.

- ↑ Browne, Rachel (20 July 2008). "Sadistic sex movie ban 'attacks art expression'". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ↑ "Film Censorship: Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)". Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Bodey, Michael (6 May 2010). "Pier Paolo Pasolini's Salo cleared for DVD release". The Australian. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Bodey, Michael (16 April 2010). "Sex-torture film cleared". The Australian. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Lane, Terry (1 March 1998). "Salo is re-banned (in Australia)". The Sunday Age. Libertus.net. Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ↑ "Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) -1 - Censor - Refused-Classification.com". refused-classification.com. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ "Salo". JB Hi-Fi. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Salo (Blu-ray)". JB Hi-Fi. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "NZ Register of Classification Decisions". Office of Film & Literature Classification. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Who voted for which film". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Goodsell, Luke (18 June 2012). "Five Favorite Films with David Cross". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Lordygan, Kerr (5 November 2015). "Gaspar Noe's Five Favorite Films". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ "Rainer Werner Fassbinder / Favourite Films". They Shoot Pictures. Bill Geogaris. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "100 Best Films of the 20th Century by the Village Voice Critics' Poll". Filmsite. AMC. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Waters, John (17 September 2010). "Why You Should Watch Filth". Big Think. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Saló, o le Centoventi Giornate di Sodoma". Time Out. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ↑ "Salo, Or The 120 Days Of Sodom Review". TV Guide.com. TV Guide. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (2010-09-14). "Questions for the Movie Answer Man". Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2011. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 9781449406189.

- ↑ Haglund, David (4 October 2011). "Must Film Buffs Watch the Revolting Salò?". Slate. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom". Chicago Reader. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Salò (DVD).

- ↑ "Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom (1976) - The Criterion Collection". Criterion. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ Barber 2010, pp. 99–102.

- ↑ Annovi 2007, p. 176.

- ↑ Mathjis & Sexton 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ Mathjis, Ernest; Mendik, Xavier (2011). 100 Cult Films. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-844-57571-8.

- ↑ Hyland, Jenn; Shorey, Eric (2013). ""You Had Me at 'I'm Dead'": Porn, Horror, and the Fragmented Body". In Och, Dana; Strayer, Kirsten. Transnational Horror Across Visual Media: Fragmented Bodies. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-136-74484-6.

- ↑ "The Essential 100". Toronto International Film Festival. Toronto International Film Festival Inc. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Strauss: Salome". Opus Arte. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Karalis, Vrasidas (2012). A History of Greek Cinema. New York City: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 268. ISBN 1441135006.

- ↑ Kermode, Mark (writer); Algar, Nigel (director) (2001). Salò: Fade to Black (Documentary).

Works cited

- Annovi, Gian Maria (2017). Pier Paolo Pasolini: Performing Authorship. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54270-8.

- Barber, Stephen (2010). "The Last Film, the Last Book". In Cline, John; Weiner, Robert G. From the Arthouse to the Grindhouse: Highbrow and Lowbrow Transgression in Cinema's First Century. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-87655-2.

- Gundle, S.; Rinaldi, Lucia (2007). Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy: Transformations in Society and Culture. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-60691-3.

- Mathjis, Ernest; Sexton, Jamie (2011). Cult Cinema. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17373-5.

- Moliterno, Gino (2009). The A to Z of Italian Cinema. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-87059-8.

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo; Biette, Jean-Claude; Davoli, Ninetto; et al. (2002). "Salò": Yesterday and Today (Documentary)

|format=requires|url=(help) (Blu-ray) (in Italian and English). The Criterion Collection. - Wells, Jeff (2008). Rigorous Intuition: What You Don't Know Can't Hurt Them. Trine Day. ISBN 978-1-937-58470-2.

Further reading

- Gary Indiana. Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma. London: British Film Institute, 2000.

- Jack Fritscher. "Toward an Understanding of Salo", Drummer, 20, January 1978, pp, 66–67, reprinted in Jack Fritscher, Mapplethorpe, Assault with a Deadly Camera, Palm Drive Publishing, 1988, ISBN 1890834297; reprinted with historical introduction in Jack Fritscher, Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer, Palm Drive Publishing 2008, ISBN 1890834386, pp. 619–642.

Essential bibliography

- Roland Barthes. Sade/Fourier/Loyola. Trans. Richard Miller. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Maurice Blanchot. Lautréamont and Sade. Trans. Stuart Kendell and Michelle Kendell. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004.

- Simone de Beauvoir. Must We Burn Sade? Trans. Annette Michelson. In Donatien Alphonse François Marquis de Sade, The 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings, trans. and eds. Austryn Wainhouse and Richard Seaver. New York City: Grove Press, 1966, pp. 3–64.

- Pierre Klossowski. Sade My Neighbor. Trans. Alphonso Lingis. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991.

- Philippe Sollers. Writing and the Experience of Limits. Trans. and eds. Philip Bernard and David Hayman. New York City: Columbia University Press, 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma. |

- Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom on IMDb

- Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom at the TCM Movie Database

- Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom at Rotten Tomatoes

- Salò an essay by John Powers at the Criterion Collection