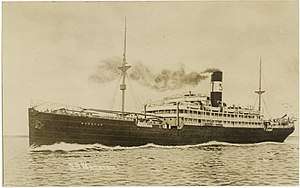

SS Waratah

Postcard of SS Waratah | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Waratah |

| Namesake: | Waratah |

| Owner: | W. Lund and Sons |

| Operator: | Blue Anchor Line |

| Route: | London, England, to Adelaide, Australia, via Durban, South Africa |

| Ordered: | September 1907 |

| Builder: | Barclay, Curle & Co., Whiteinch, Scotland |

| Cost: | £139,900 |

| Yard number: | 472 |

| Launched: | 12 September 1908 |

| Sponsored by: | Mrs. J. W. Taverner |

| Completed: | 23 October 1908 |

| Maiden voyage: | 5 November 1908 |

| Homeport: | London |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | Disappeared without trace south off Durban, July 1909 |

| Status: | Missing, presumed sunk. |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger Cargo Ship |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 465 ft 0 in (141.73 m) |

| Beam: | 59 ft 4 in (18.08 m) |

| Depth: | 27 ft 0 in (8.23 m) |

| Installed power: | 1,003 Nhp[1] |

| Propulsion: | 2 × Barclay, Curle & Co. 4-cylinder quadruple expansion reciprocating steam engines |

| Speed: | Approximately 13.5 kn (25.0 km/h) service speed. |

| Capacity: | 432 passenger cabin berths, plus over 600 spaces in dormitories in the holds |

| Crew: | 154 crew |

| Notes: | Waratah cost £139,900 to build, and had lifeboat/raft space for 921 people |

SS Waratah was a passenger and cargo steamship built in 1908 for the Blue Anchor Line to operate between Europe and Australia. In July 1909, on only her second voyage, the ship, en route from Durban to Cape Town, disappeared with 211 passengers and crew aboard. To this day, no trace of the ship has been found.

Design and construction

In September 1907 W. Lund & Sons placed an order with Barclay, Curle & Co. of Glasgow for a new cargo and passenger vessel to be delivered within 12 month that was specially designed for their Blue Anchor Line trade between United Kingdom and Australia. The owners wanted the ship to be an improved version of their existing steamer SS Geelong and therefore most specifications were based upon those of Geelong. The vessel was laid down at Barclay, Curle & Co's Clydeholm Yard in Whiteinch and launched on 12 September 1908 (yard number 4722), with Mrs J. W. Taverner, wife of the Agent-General of Victoria, being the sponsor.[2][3] The ship was of the spar-deck type, and had three complete decks - lower, main and spar. The first-class accommodations were built on the promenade, bridge and boat decks and could house 128 passengers. In addition, a nursery was provided on the ship for first-class passenger's convenience. The vessel also had third-class passenger accommodations constructed on the poop deck that could house upward of 300 people, but was only certified for 160. Waratah was constructed for both speed and luxury, and had eight state rooms and a salon whose panels depicted its namesake flower, as well as a luxurious music lounge complete with a minstrel's gallery. Waratah had a cellular double bottom built along her entire length, and the hull was divided into eight watertight compartments, which it was claimed rendered her "practically immune from any danger of sinking."[4] With an intent of being also an emigrant ship, her cargo holds would be converted into large dormitories capable of holding almost 700 steerage passengers on the outward journeys, while on the return the steamer would be laden with general cargo, mainly frozen meat, dairy products, wool and metal ore from Australia. In order to be able to carry frozen produce, her entire front end was fitted with refrigerating machinery and cold chambers. She also had Kirkcaldy's distilling apparatus installed on-board capable of producing 5,500 imp gal (25,000 litres) of fresh water a day. At the time of construction, Waratah was not equipped with a radio, which was not unusual at the time.[5]

The sea trials were held on October 23, 1908 on the Firth of Clyde, during which the steamer was able to successfully maintain a mean speed of 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h) over several runs on the measured mile. After successful completion of sea trials the ship was transferred to her owners on the same day and immediately departed for London.[6]

As built, the ship was 465 feet 0 inches (141.73 m) long (between perpendiculars) and 59 feet 4 inches (18.08 m) abeam, a mean draft of 30 feet 4 1⁄2 inches (9.258 m).[1] Waratah was assessed at 9,339 GRT and 6,004 NRT and had deadweight of approximately 10,000.[1] The vessel had a steel hull, and two sets of quadruple-expansion steam engines, with cylinders of 23-inch (58 cm), 32 1⁄2-inch (83 cm), 46 1⁄2-inch (118 cm) and 67-inch (170 cm) diameter with a 48-inch (120 cm) stroke, that provided a combined 1,003 nhp and drove two screw propellers, and moved the ship at up to 13 1⁄2 knots (15.5 mph; 25.0 km/h).[1]

The ship was named after the emblem flower of New South Wales which appears to have been an unlucky name: one ship of that name had been lost off the island of Ushant in the English Channel in 1848, one in 1887 on a voyage to Sydney, another south of Sydney, and one in the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1897.[7][3]

Operational history

Following delivery, Waratah left London for her maiden voyage on 5 November 1908 with 689 third-class and 67 first-class passengers.[8][9] She was under command of captain Joshua Edward Ilbery, a veteran of the Blue Anchor Line with 30 years of nautical experience, and a previous master of SS Geelong, and had a crew of 154. She touched off at Cape Town on November 27 and arrived at Adelaide on December 15, 1908.[10] Among her passengers were Hamilton Wickes, a newly appointed British Trade Commissioner for the Commonwealth, Dr. Anderson, Bishop of Riverina and Octavius Beale, president of the Federal Council of Chambers of Manufactures.[11] From Adelaide the steamer proceeded to Melbourne and Sydney and sailed back for London on January 9, 1909 via Australian and South African ports carrying cargo of foodstuffs, wool, and 1,500 tons of metal concentrates.[12] Waratah arrived in London on March 7, 1909 to finalize her maiden voyage, and after disembarking her cargo, was put into drydock where she was inspected by the Lloyd's inspector, and also undergone some minor repairs.

While on her maiden voyage, early in the morning of December 6, 1908, second officer reported a small fire in lower starboard bunker extending all the way to the engine room. The fire was largely brought under control by noon on the same day but continued reigniting all the way through December 10. The fire was apparently caused by the heat emitted by several reducing and steam valves located on the starboard side of the engine room. While the roof of the engine room was insulated, the starboard side was evidently not. The repairs were performed at Sydney to the chief engineer's satisfaction.

During her maiden trip the steamer was scrutinized by the captain and the crew, as one of the criteria used in acceptance trials was the ship's handling and stability. Captain Ilbery was not completely satisfied and, considering he was previously in charge of Geelong, presumably reported to the owners the ship did not have the same stability as his old vessel. He was especially concerned with the difficulty of properly stowing the steamer to maintain her stability, which ensued in quite a heated exchange between the owners and the builders following the vessel's return to England.

The subsequent inquiry into her sinking raised some disputed reports of instability on this voyage.[13]

On 27 April 1909 Waratah set out on her second trip to Australia carrying 22 cabin, 193 steerage passengers in addition to a large cargo of general merchandise, and had a crew of 119. The outward trip was largely uneventful, and the steamer arrived at Adelaide on June 6 after touching off at Cape Town on May 18. Upon loading approximately 970 tons of lead ore at Adelaide, the steamer continued to Melbourne and had to plow through a strong gale which also complicated her berthing upon arrival there on June 11.[14] She continued on to Sydney where she loaded her cargo for return voyage consisting among other things of 7,800 bars bullion, wool, frozen meat, dairy and flour and departed on June 26.[15] She stopped to complete her loading at Melbourne and Adelaide and set out from Adelaide on July 7 bound for the South African ports of Durban and Cape Town and continuing to Europe.[16][17] Aside from almost 100 passengers, she also had onboard a convict being extradited to South Africa, accompanied by two Transvaal policemen.[18] Waratah reached Durban in the morning of July 25, where one passenger, Claude G. Sawyer, an engineer and experienced sea traveller, left the ship and sent the following cable to his wife in London: "Thought Waratah top-heavy, landed Durban".

The Waratah left Durban at approximately 20:15 on 26 July with 211 passengers and crew. At around 04:00 on 27 July she was spotted astern on the starboard side by the chief officer of the steamer Clan McIntyre. By about 06:00 Waratah was abeam of Clan McIntyre and approximately 2-3 miles away, at which point both vessels exchanged signals. Waratah then sped up, going approximately 13 knots, crossed Clan McIntyre's bow, and disappeared over the horizon by about 09:30. Later that day, the weather deteriorated quickly (as is common in that area), with increasing wind and rough seas. On July 28 a gale sprang out in the area, so bad that Clan McIntyre could only make 32 miles in 24 hours through noon on July 29, with wind gusting to 50 knots (58 mph; 93 km/h) combined against the tide and ocean swell to build waves up to 30 feet (9.1 m), forcing the vessel to pitch heavily. That evening the Union-Castle Liner Guelph, heading north to Durban from the Cape of Good Hope, passed a ship and exchanged signals by lamp, but because of the bad weather and poor visibility was able to identify only the last three letters of her name as "T-A-H."

The same evening, a ship called the Harlow saw a large steamer coming up astern of her, working hard in the heavy seas and making a great deal of smoke, enough to make her captain wonder if the steamer was on fire. When darkness fell, the crew of the Harlow could see the steamer's running lights approaching, but still 10 to 12 miles (16 to 19 km) behind them, when there were suddenly two bright flashes from the vicinity of the steamer and the lights vanished. The mate of the Harlow thought the flashes were brush fires on the shore (a common phenomenon in the area at that time of year). The captain agreed and did not even enter the events in the log – only when he learnt of the disappearance of the Waratah did he think the events significant.[19] Reportedly the Harlow was 180 miles (290 km) from Durban.[20][21]

The Waratah was expected to reach Cape Town on 29 July 1909, but never reached its destination. No trace of the ship has ever been found.

Search efforts

Initially, it was believed that the Waratah was still adrift. The Royal Navy deployed cruisers HMS Pandora and HMS Forte (and later HMS Hermes) to search for the Waratah. The Hermes, near the area of the last sighting of the Waratah, encountered waves so large and strong that she strained her hull and had to be placed in dry dock on her return to port.[22] On 10 August 1909, a cable from South Africa reached Australia, reading "Blue Anchor vessel sighted a considerable distance out. Slowly making for Durban. Could be the Waratah". The Chair of the House of Representatives in the Australian Parliament halted proceedings to read out the cable, saying: "Mr. Speaker has just informed me that he has news on reliable authority that the SS Waratah has been sighted making slowly towards Durban." [23] In Adelaide, the town bells were rung, but the ship in question was not the Waratah.

On 13 August 1909 the steamship Insizwa reported sighting of several bodies off the mouth of Bashee (Mbashe) River.[24] The captain of the Tottenham also allegedly saw bodies in the water, more than two weeks after the Waratah disappeared.[25] The Warratah's sister ship Geelong deviated from its course from Cape Town to Adelaide, to search waters east of South Africa where the Waratah was thought to be possibly drifting.[26] The German steamship Goslar also kept special lookout for Waratah for 1262 miles of ocean while en route from Port Elizabeth to Melbourne.[27] In September 1909, the Blue Anchor Line chartered the Union Castle ship Sabine to search for the Waratah. The search by the Sabine covered 14,000 miles, but yielded no result. In 1910 relatives of Waratah passengers chartered the Wakefield and conducted a search for three months, which again proved unsuccessful. The same year the official enquiry into the fate of the Waratah was held in London during December. Among others, Claude Sawyer, the engineer who had thought the ship top-heavy and thus disembarked at Durban, gave testimony.

Some wreckage—possibly from the Waratah—is reported to have been found at Mossel Bay in March 1910.[28] A life preserver marked with the name 'Waratah' washed up on the coast of New Zealand in February 1912.[25] In 1925 Lt. D. J. Roos of the South African Air Force reported that he had spotted a wreck while he was flying over the Transkei coast. It was his opinion that this was the wreck of the Waratah. Pieces of cork and timber, possibly from the Waratah, were washed up near East London, South Africa in 1939.[29]

In 1977 a wreck was located off the mouth of the Xora River. Several investigations into this wreck, in particular under the leadership of Emlyn Brown, took place. It is however widely believed today that the wreck off the Xora River was that of one of many ships which had fallen victim to German U-boats during the Second World War. It has proven particularly difficult to explain why the Waratah should be found so far to the north of her estimated position. Further attempts to locate the Waratah took place in 1991, 1995 and 1997. In 1999 reports reached the newspapers that the Waratah had been found 10 km off the eastern coast of South Africa.[30] A sonar scan conducted by Emlyn Brown's team had indeed located a wreck whose outline seemed to match that of the Waratah. In 2001, however, a closer inspection revealed differences between the Waratah and the wreck. It appears that the team had in fact found the Nailsea Meadow, a ship that had been sunk in the Second World War.[31] In 2004 Emlyn Brown, who had by then spent 22 years looking for the Waratah, declared that he was giving up the search: "I've exhausted all the options. I now have no idea where to look", he said.[32]

Inquiry

The Board of Trade inquiry into the disappearance quickly came to focus on the supposed instability of the Waratah.[33] Evidence was greatly hampered by the lack of any survivors from the ship's final voyage (other than the small number, including Claude Sawyer, who had disembarked in Durban). Most evidence came from passengers and crew from Waratah's maiden voyage, her builders and those who had handled her in port.

The expert witnesses all agreed that the Waratah was designed and built properly and sailed in good condition.[34] She had passed numerous inspections, including those by her builders, her owners, the Board of Trade and two by Lloyd's of London, who gave her the classification "+100 A1" – their top rating,[35] granted only to ships Lloyds had inspected and assessed throughout the design, construction, fitting out and sea trials, on top of the two valuations and inspections Lloyds had made of the completed Waratah.

Many witnesses who had travelled of the ship testified that the Waratah felt unstable, frequently listed to one side even in calm conditions, had a very long roll (a reluctance to right herself after leaning into a swell) and had a tendency for her bow to dip into oncoming waves rather than ride over them.[13][36][37] One passenger on her maiden voyage said that when in the Southern Ocean she developed a list to starboard to such an extent that water would not run out of the baths, and she held this list for several hours before rolling upright. This passenger, physicist Professor William Bragg, concluded that the ship's metacentre was just below her centre of gravity. When slowly rolled over towards one side, she reached a point of equilibrium and would stay leaning over until a shift in the sea or wind pushed her upright.[38][36]

Other passengers and crew members commented on her lack of stability, and those responsible for handling the ship in port said she was so unstable when unladen that she could not be moved without ballast.[39] But for every witness of this opinion, another could be found who said the opposite. Both former passengers and crew members (ranking from stokers to a deck officer) said the Waratah was perfectly stable, with a comfortable, easy roll.[40] Many said they felt she was especially stable.[41] The ship's builders produced calculations to prove that even with a load of coal on her deck (that several witnesses claim she was carrying when she left Durban) she was not top heavy.[34]

The inquiry was unable to make any conclusions from this mixed and contradictory evidence. It did not blame the Blue Anchor Line, but did make several negative comments in regard to the company's practices in determining the performance and seaworthiness of its new ships.[42] Correspondence between Captain Ilbery and the line's managers show he commented on numerous details about the ship's fixtures, fittings, cabins, public rooms, ventilation and other areas, but failed to make any mention at the basic level of the Waratah's seaworthiness and handling. Equally, the company never asked Captain Ilbery about these areas.[43] This led many to speculate that Ilbery had concerns about the Waratah and its stability, but deliberately kept such doubts quiet. However, it is also possible that neither he nor the Blue Anchor Line felt it necessary to cover such areas, because the Waratah was heavily based on a previous (and highly successful) Blue Anchor ship, the Geelong, and so the Waratah's handling was assumed to be the same.

It is certainly true that many passenger ships of the period were made slightly top-heavy. This produced a long, comfortable but unstable roll, which many passengers preferred to a short, jarring but stable roll. Many trans-Atlantic liners were designed this way, and after a few voyages those operating them learnt how to load, ballast and handle them correctly and the ships completed decades of trouble-free service. It may have been the Waratah's misfortune to encounter an unusually heavy storm or freak wave on only her second voyage, before she could be trimmed correctly. This slightly top-heavy design could also account for the strongly opposed opinions of witnesses about whether or not the ship felt stable. An inexperienced or uninformed person on the ship might conclude that the long, slow, soft roll of the ship felt comfortable and safe, whilst someone with more seagoing experience or a knowledge of ship design would have felt that the same motion was unstable. In regards to the witnesses claiming the Waratah's instability in port when unladen, this may have been true. However, virtually all ocean-going ships (which are, after all, designed to carry a large weight of cargo) need to be ballasted to some extent when moved unladen, so the Waratah was certainly not unique in this respect. The witnesses would have been well aware of this – that they still came forward to attest that they regarded the Waratah as dangerously unstable in these conditions does suggest that the ship was exceptional in some respect.

The Waratah was also a mixed-use ship. Passenger liners, with a small cargo volume relative to their gross tonnage had fairly constant and predictable ballasting requirements. A ship like the Waratah would carry a wide range of cargoes, and even different cargoes on the same voyage, making the matter of ballasting both more complex and more crucial.[44] When she disappeared, the Waratah was carrying a cargo of 1,000 tons of lead concentrate, which may have suddenly shifted, causing the ship to capsize.[45]

The inquiry concluded that the three ships reporting potential sightings of the Waratah on the evening of 26 July could not all have seen her given the distance between them and the time of the sightings, unless the Waratah had reached Mbashe River and exchanged signals with the Clan MacIntyre but then turned around and headed back to Durban, to be sighted by the Harlow.

Other theories

Freak wave

A theory advanced to explain the disappearance of the Waratah is an encounter with a freak wave, also known as a rogue wave, in the ocean off the South African coast.[46] Such waves are known to be common in that area of the ocean. It is most likely that the Waratah, with what seems to be marginal stability and already ploughing through a severe storm, was hit by a giant wave. This either rolled the ship over outright or stove in her cargo hatches, filling the holds with water and pulling the ship down almost instantly. If the ship capsized or rolled over completely, any buoyant debris would be trapped under the wreck, explaining the lack of any bodies or wreckage in the area. This theory was given credibility through a paper by Professor Mallory of the University of Cape Town (1973) which suggested that waves of up to 20 metres (66 feet) in height did occur between Richards Bay and Cape Agulhas. This theory also stands up if the Waratah is assumed to have been stable and seaworthy – several ships around the Cape of Good Hope have been severely damaged and nearly sunk by freak waves flooding their holds. Throughout the world ships such as Melanie Schulte (a German ship lost in the Atlantic Ocean) [47] and MV Derbyshire (a British bulk carrier sunk in the Pacific Ocean) have suddenly broken up and sunk within minutes in extreme weather.

Some have also suggested that instead of sinking, the ship was incapacitated by a freak wave and, having lost her rudder and without any means of contacting land, was swept southwards towards Antarctica to either be lost in the open ocean or founder on Antarctica itself. No evidence except the absence of the wreck supports this theory, however.

Whirlpool

Both at the time of the disappearance and since, several people have suggested that the Waratah was caught in a whirlpool created by a combination of winds, currents and a deep ocean trench, several of which are known to be off the southeast coast of Africa. This would explain the lack of wreckage, but there is no firm evidence that a whirlpool of sufficient strength to almost instantly suck down a 450-foot-long (140 m) ocean liner could be created as suggested.[48]

Explosion

Given the evidence from the officers of the Harlow (see above), it has been speculated that the Waratah was destroyed by a sudden explosion in one of her coal bunkers. Coal dust can certainly self-combust and in the right proportions of air be explosive. However, no single bunker explosion would cause a ship the size of the Waratah to sink instantly, without anyone being able to launch a lifeboat or raft, and without leaving any wreckage.[49]

Paranormal

Several supernatural theories were also put forward to explain the disappearance of the Waratah. Claude Sawyer reported to the London inquiry that he had during the voyage seen on three occasions in dreams the vision of a man "dressed in a very peculiar dress, which I had never seen before, with a long sword in his right hand, which he seemed to be holding between us. In the other hand he had a rag covered with blood." He decided that this vision was a warning, and was one of the reasons why he decided not to continue the voyage on the Waratah and to get off the ship at Durban.[50][36]

Aftermath

The Waratah's disappearance, the inquiry and the criticism of the Blue Anchor Line generated much negative publicity. The line's ticket sales dropped severely, and coupled with the huge financial loss taken in the construction of the Waratah (which like many ships of the time, was under-insured), forced the company to sell its other ships to its main competitor P&O and declare voluntary liquidation in 1910.[51]

In 1913, a Brisbane newspaper, The Daily Mail, suspected its competitor The Daily Standard was copying its news stories. So the Daily Mail published a hoax article claiming that the Waratah had been discovered in Antarctica.[52][53] The Daily Standard also published the story and added a statement from the harbourmaster.[54][55]

Memorials

There is a plaque in the Parish Church at Buckland Filleigh, Devon, England, commemorating Col. Percival John Browne. He was returning to England on the Waratah, from his sheep farm in Mount Gambier, South Australia. His family home was Buckland House.

A plaque to the memory of Howard Cecil Fulford, the ship's surgeon, was erected in the chapel by his fellow students at Trinity College (University of Melbourne).

In the Parish Church of St. Wilfrid, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, England, is a plaque: "The church gates were given in memory of Harris Archibald Gibbs who was drowned at sea in the SS Waratah".

In the main church in Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, Wales, is a plate "in happy memory of John Purton Morgan, 3rd Officer SS Waratah lost at sea 1909".

A memorial in Higher Cemetery, Exeter, Devon, commemorates Thomas Newman "drowned in SS Waratah 27th July 1909".

A centenary plaque was unveiled at the Queenscliffe Maritime Museum, Victoria, Australia, on 27 July 2009.[56]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lloyd's Register, Steamships and Motorships. London: Lloyd's Register. 1909–1910.

- ↑ "Waratah (1125741)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Launches-Scotch". Marine Engineer & Naval Architect. XXXI. 1 October 1908. p. 92.

- ↑ "S.S. Waratah". The Albany Advertiser. XXI, (2708). Western Australia. 20 January 1909. p. 3. Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 118

- ↑ "Trial Trips". Marine Engineer & Naval Architect. XXXI. 1 December 1908. p. 177.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 117

- ↑ "The Tide of Immigration". Sunday Times (1190). New South Wales, Australia. 8 November 1908. p. 7. Retrieved 30 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 119

- ↑ "The Liner Waratah". Evening Journal. XLII, (11776). South Australia. 15 December 1908. p. 1. Retrieved 30 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Personal". The Advertiser. LI, (15, 652). South Australia. 16 December 1908. p. 9. Retrieved 30 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Week's Shipments". Daily Commercial News And Shipping List (5673). New South Wales, Australia. 12 January 1909. p. 14. Retrieved 30 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "THE S.S. WARATAH. HER MAIDEN VOYAGE. A REMINISCENCE". The Daily News. XXVIII, (10, 695). Western Australia. 14 September 1909. p. 2 (THIRD EDITION). Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Berthing of the Waratah". The Age (16, 925). Victoria, Australia. 12 June 1909. p. 14. Retrieved 30 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Exports". Daily Commercial News And Shipping List (5817). New South Wales, Australia. 5 July 1909. p. 2. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Shipping News". The Express And Telegraph. XLVI, (13, 751). South Australia. 8 July 1909. p. 1 (4 o'clock.). Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Grain Trade". The Australasian. LXXXVII, (2, 258). Victoria, Australia. 10 July 1909. p. 9. Retrieved 2 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Charged with Murder". Evening Journal. XLIII, (11944). South Australia. 8 July 1909. p. 1. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Harris (1989), pp. 122, 138

- ↑ "Saw Steamer Blow Up". The New York Times. 21 September 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Loss of the Waratah". The Times. 24 September 1909. p. 12. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 125

- ↑ Hansard, House of Representatives p2228 10 August 1909

- ↑ "Probably Waratah Victims". The Boston Globe. 13 August 1909. p. 9. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 SS Waratah, Stories and Legends

- ↑ "A LUND LINER'S TRIP". The Age (16, 995). Victoria, Australia. 2 September 1909. p. 7. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE GOSLAR'S SEARCH". The Age (16, 995). Victoria, Australia. 2 September 1909. p. 7. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald 4 March 1910

- ↑ Fairplay Weekly Shipping Journal, Volume 150 1939 .p.70

- ↑ Addley

- ↑ "Search for Waratah goes on after 'false' find". IOL. 24 January 2001. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ "'Titanic' hunt draws a blank". The Guardian. 4 May 2004. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 129

- 1 2 Harris (1989), p. 130

- ↑ Harris (1989), pp. 118, 130

- 1 2 3 "THE WARATAH. A PROFESSOR'S ALARM: SAVED BY A VISION. MISS HAY WARNED". The Advertiser. LIII, (16, 306). South Australia. 20 January 1911. p. 7. Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "LOSS OF THE S.S. WARATAH. SENSATIONAL EVIDENCE (The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser 21 February 1911)". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 131

- ↑ Harris (1989), pp. 130, 140

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 133

- ↑ "THE S.S. WARATAH AND HER COMMANDER". The Advertiser. LI, (15, 652). South Australia. 16 December 1908. p. 10. Retrieved 4 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 141

- ↑ Harris (1989), pp. 139–141

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 146

- ↑ Harris (1989)

- ↑ "Monsters of the deep – Huge, freak waves may not be as rare as once thought". Economist Magazine. 17 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 149

- ↑ Harris (1989), pp. 147–49

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 48

- ↑ Harris (1989), p. 120

- ↑ Blue Anchor Line Archived 12 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sinnamon, Myles (15 April 2017). "Backstory 1913". The Courier-Mail: QWeekend Supplement. p. 37.

- ↑ "Echoes from the Capital". Cairns Post. XXVI, (17010). Queensland, Australia. 11 September 1913. p. 2. Retrieved 16 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "ENCASED IN ICE". Daily Standard (228). Queensland, Australia. 5 September 1913. p. 5 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved 16 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ ""NO REASONABLE DOUBT."". Daily Standard (228). Queensland, Australia. 5 September 1913. p. 5 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved 16 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "S.S. Waratah". Monument Australia. Archived from the original on 2018-01-24. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

Bibliography

- Harris, John (1989), Without Trace: The Last Voyages of Eight Ships, Mandarin, ISBN 0-7493-0043-4

Further reading

- "The Loss of the Waratah", The Times, 23 February 1911 p. 24

- Esther Addley, "Sea yields our Titanic's Resting Place", The Weekend Australian, 17 July 1999

- Sue Blane, "The Week in Quotes", Financial Times, 6 May 2004

- Alan Laing, "Shipwreck expert abandons hunt for Clyde liner", The Herald, 4 May 2004

- Tom Martin, "Almost a century after she vanished, scientists could now be on the verge of solving riddle of SS Waratah's last voyage", Sunday Express, 25 April 2004

- Geoffrey Jenkins' Scend of the Sea (Collins, 1971) is a novel based on the loss of the Waratah.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waratah (ship, 1908). |

- S/S Waratah on the wrecksite

- NUMA on Waratah

- Waratah Crew list

- Waratah Passenger list

- December 1910 inquiry into loss of Waratah .pp.101-105