Russian presidential election, 2000

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout |

68.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in Russia on 26 March 2000.[1] Incumbent Prime Minister and acting President Vladimir Putin, who had succeeded Boris Yeltsin on his resignation on 31 December 1999, was seeking a four-year term in his own right and won the elections in the first round.

Background

In spring 1998, Boris Yeltsin dismissed his long-time head of government, Viktor Chernomyrdin, replacing him with Sergey Kirienko. Months later, in the wake of the August 1998 economic crisis in which the government defaulted on its debt and devalued the rouble simultaneously, Kirienko was replaced in favor of Yevgeny Primakov. In May 1999, Primakov was replaced with Sergei Stepashin. Then in August 1999, Vladimir Putin was named Prime Minister, making him the 5th in less than two years.[2] Putin was not expected to last long in the role and was initially unknown and unpopular due to his ties to the Yeltsin government and state security. In the late summer and early fall of 1999, a wave of apartment bombings across Russia killed hundreds, injured thousands. The bombings, blamed on the Chechens, provided the opportunity for Putin to position himself as a strong and aggressive leader, capable of dealing with the Chechen threat.

Yeltsin had become exceedingly unpopular. Yeltsin was increasingly concerned about the Skuratov, Mercata and Mabetex scandals that had prompted articles of impeachment.[3] He narrowly survived impeachment in May 1999. In mid-1999, Yevgeny Primakov and Yuri Luzhkov were considered the frontrunners for the presidency.[3] Both were critical of Yeltsin, and he feared that they might prosecute him and his “Family” for corruption should they ascend to power.[4] Primakov had suggested that he would be “freeing up jail cells for the economic criminals he planned to arrest.”[5]

On December 19, 1999, the Kremlin’s Unity Party finished second in the Parliamentary elections with 23 percent; the Communist Party was first with 24 percent.[3] By forming a coalition with Yabloko and the Union of Right Forces,[3] Yeltsin had secured a favorable majority in the Duma. By the December election, Putin’s popularity had risen to 79% with 42% saying they would vote for him for President.[5]

On New Year's Eve 1999, Yeltsin announced that he would be resigning early in the belief that “Russia should enter the new millennium with new politicians, new faces, new people, who are intelligent, strong and energetic, while we, those who have been in power for many years, must leave.”[3] In accordance with the constitution, Putin became acting president.

The elections would be held on 26 March 2000. In early 2000, Unity and the Communist Party had developed an alliance in the Duma that effectively cut off Putin’s rivals, Yevgeny Primakov, Grigory Yavlinsky, and Sergei Kiriyenko.[3] Yuri Luzhkov, the reelected Mayor of Moscow, announced that he would not compete for the presidency; Primakov pulled out two weeks after the Parliamentary elections.[3] The early election also reduced the chances that public sentiment would turn against the conflict in Chechnya.[6]

New campaign law

A new federal law, “On the election of the president of the Russian Federation” was passed in December 1999. It required that candidates gather a million signatures to be nominated (although the shortened election meant this was reduced to 500,000).[6] A majority in the first round was enough to win. Failing that, a second round of voting between the top two candidates would be decided by majority vote.[6] The new law also created stricter campaign finance provisions.[6] The new law, in conjunction with the early election would have further helped Putin, who could rely on favorable state television coverage.

Candidates

A total of 33 candidates were nominated; 15 submitted the application forms to the Central Electoral Committee, and ultimately 12 candidates were registered:[6]

Registered candidates

Candidates are listed in the order they appear on the ballot paper (alphabetical order in Russian).

| Candidate name, age, political party |

Political offices | Registration date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanislav Govorukhin (64) Independent |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1994-2003 and 2005–2018) Film director |

15 February 2000 | |

| Umar Dzhabrailov (41) Independent |

.jpg) |

Businessman | 18 February 2000 | |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky (53) Liberal Democratic Party |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1993-present) Leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (1991-present) |

2 March 2000 | |

| Gennady Zyuganov (55) Communist Party |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1993-present) Leader of the Communist Party (1993-present) |

28 January 2000 | |

| Ella Pamfilova (46) For Civic Dignity |

|

Minister of Social Protection of the Population of Russia (1991-1994) |

15 February 2000 | |

| Alexey Podberezkin (47) Spiritual Heritage |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1995-1999) |

29 January 2000 | |

| Vladimir Putin (47) Independent (campaign) |

|

Acting President of Russia (1999-2000) Prime Minister of Russia (1999-2000) Director of the Federal Security Service (1998-1999) |

7 February 2000 | |

| Yury Skuratov (47) Independent |

|

Prosecutor General of Russia (1995-1999) |

18 February 2000 | |

| Konstantin Titov (55) Independent |

|

Governor of Samara Oblast (1991-2007) |

10 February 2000 | |

| Aman Tuleyev (55) Independent |

.jpg) |

Governor of Kemerovo Oblast (1997-2018) |

7 February 2000 | |

| Grigory Yavlinsky (47) Yabloko |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1994-2003) Leader of the Yabloko party (1993-2008) |

15 February 2000 | |

Withdrawn candidates

| Candidate name, age, political party |

Political offices | Details | Registration date | Date of withdrawal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yevgeny Savostyanov (48) Independent |

Kremlin Deputy Chief of Staff (1996-1998) |

Supported Grigory Yavlinsky. | 18 February 2000 | 21 March 2000 | ||

Campaign

.jpg)

Gennady Zyuganov and Grigory Yavlinsky were the two strongest opposition candidates. Zyuganov ran on a platform of resistance to wholesale public ownership although illegally privatized property would be returned to the state.[6] He opposed public land ownership and advocated for strong public services to be provided by the state. He would also strengthen the country’s defense capabilities and would resist expansion by the United States and NATO.[6] Grigorii Yavlinsky (Yabloko) ran as a free marketer but with measured state control.[6] He wanted stronger oversight of public money, an end to the black market and reform of the tax system coinciding with an increase in public services.[6] He also advocated for a strengthened role for the Duma and a reduction in the size of the civil bureaucracy.[6] He was the most pro-Western candidate, but only to an extent: he had been critical of the war in Chechnya but remained skeptical of NATO.[6] One of Putin’s major campaign platforms was “dictatorship of the law” and “the stronger the state, the freer the people.”[2]

Putin mounted almost no campaign in advance of the 2000 elections. “He held no rallies, gave no speeches, and refused to participate in debates with his challengers.”[3] The extent of Putin’s campaign was a biographical interview broadcast on State Television, and a series of interviews with journalists, paid for by Boris Berezovsky, an oligarch who had helped to build the Unity Party in the Yeltsin years.[3] Putin’s platform was best reflected by an “Open letter to Russian voters” that ran in national newspapers on February 25, 2000.[6] Because he refused to participate in the debates, Putin’s challengers had no venue in which to challenge his program, vague as it may be.[6] A number of other candidates explained this as a refusal to clarify his position on various controversial issues.

Uncritical state television coverage of Putin’s oversight of the conflict in Chechnya helped him to consolidate his popularity as Prime Minister, even as Yeltsin’s popularity as President fell.[6] Analysis of television coverage of the 1999 Duma and 2000 Presidential elections found that “it was ORT, and state television more generally, that had helped to create a party on short notice”[4] and that “its coverage…was strongly supportive of the party it had created.”[4] Further, TV channel ORT aggressively attacked credible opponents to Unity and Putin.[4] Putin “received over a third of the coverage devoted to the candidates on all television channels, as much as Zyuganov (12%), Yavlinsky (11%) and Zhirinovsky (11%) put together.”[6] He received more than a third of print media coverage, and was given outsize coverage even in opposition newspapers.[6]

.jpg)

Putin announced a new press policy after he won the election. He stated that he believed in “free press” but this should not let the media become “means of mass disinformation and tools of struggle against the state.”[2] He encouraged the state owned media to control the market and provide the people with “objective information.”[2]

Conduct

The decision to conduct the presidential elections also in Chechnya was perceived as controversial by many observers due to the military campaign and security concerns.[7] The legislative elections held on 19 December 1999 had been suspended in Chechnya for these reasons.

The PACE observers delegation concluded that "the unequal access to television was one of the main reasons for a degree of unfairness of the campaign" and that "independent media have come under increasing pressure and that media in general, be they State-owned or private, failed to a large extent to provide impartial information about the election campaign and candidates."[8]

The PACE delegation also reported that the media got more and more dominated by politically influential owners. The TV channel ORT launched a slanderous campaign against Yavlinsky's image as his ratings started to rise sharply, and broadcasters generally nearly ignored candidates who did not fulfill interests of their owners. One of the main independent broadcasters, NTV, was subject to increasing financial and administrative pressure during the electoral campaign.

There were also many allegedly serious forgeries reported that could affect Putin's victory in the first round.[9][10]

Opinion polls

Results

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Putin | Independent | 39,740,434 | 53.4 |

| Gennady Zyuganov | Communist Party | 21,928,471 | 29.5 |

| Grigory Yavlinsky | Yabloko | 4,351,452 | 5.9 |

| Aman Tuleyev | Independent | 2,217,361 | 3.0 |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | 2,026,513 | 2.7 |

| Konstantin Titov | Independent[a] | 1,107,269 | 1.5 |

| Ella Pamfilova | For Civic Dignity | 758,966 | 1.0 |

| Stanislav Govorukhin | Independent | 328,723 | 0.4 |

| Yury Skuratov | Independent | 319,263 | 0.4 |

| Alexey Podberezkin | Spiritual Heritage | 98,175 | 0.1 |

| Umar Dzhabrailov | Independent | 78,498 | 0.1 |

| Against all | 1,414,648 | 1.9 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 701,003 | – | |

| Total | 75,070,776 | 100 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 109,372,046 | 68.6 | |

| Source: Central Election Commission | |||

a Titov was unofficially aligned with the Union of Rightist Forces.[11]

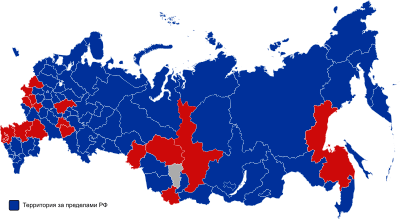

Polling stations were open from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Putin won on the first ballot with 53.4% of the vote. Putin’s highest official result was 85.42% in Ingushetia, his lowest achievement was 29.65% in neighboring Chechnya. Zyuganov’s results ranged from 47.41% in the Lipetsk region to 4.63% in Ingushetia. Yavlinsky’s results ranged from 18.56% in Moscow to 0.42% in Dagestan. Zhirinovsky’s results ranged from 6.13% in the Kamchatka region to 0.29% in Ingushetia.[12]

References

- ↑ Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1642 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- 1 2 3 4 Riasanovsky, N., Steinberg, M. (2011). A History of Russia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Myers, S. L. (2015). The new Tsar: The rise and reign of Vladimir Putin.

- 1 2 3 4 White, S., Oates, S., & McAllister, I. (2005). Media effects and Russian elections, 1999–2000. British Journal of political science, 35(02).

- 1 2 Treisman, D. (2012). The return: Russia's journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 White, S. (2001). The Russian presidential election, March 2000. Electoral Studies, 20(3).

- ↑ OSCE final report on the presidential election in the Russian Federation, 26 March 2000 OCSE

- ↑ Ad hoc Committee to observe the Russian presidential election (26 March 2000) Archived 10 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. PACE, 3 April 2000

- ↑ Election Fraud Reports The Moscow Times

- ↑ The Operation "Successor" Vladimir Pribylovsky and Yuriy Felshtinsky (in Russian)

- ↑ 2000 Presidential elections University of Essex

- ↑ Electoral Geography. Russia, Presidential Elections, 2000 Electoral Geography

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)