| Constituency |

Commentary |

Summary of vote |

Elected deputies |

|---|

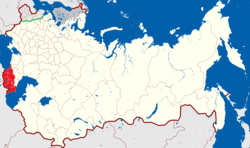

| Petrograd City |

Voter turnout in the capital was estimated at between 69.7% and 72%.[41]

The Petrograd SR branch was dominated by left-wing elements.[42]

The Kadet list (no. 2) was headed by Pavel Milyukov, followed by Maxim Vinaver, Nikolai Kutler, F.I. Rodichev, Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev, Countess Sofia Panina, Aleksandr Kornilov, D.D. Grimm, D.S. Zernov, Vladimir Vernadsky, A.N. Kolosov, A.D. Protopopov, Prince V.A. Obolensky, Sergey Oldenburg, L.A. Velikhov, K. N. Sokolov and V. M. Hessen.[43]

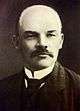

The Bolshevik (no. 4) Bolsheviks headed by Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov (Lenin), followed by Evsei Aronovich Radomyslsky (Zinoviev), Lev Davydovich Bronstein (Trotsky), Lev Borisovich Rosenfeld (Kamenev), Alexandra Kollontai, Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili (Stalin), Matvei Muranov, Mikhail Kalinin, Józef Unszlicht, Sergei Alexandrovich Cherepanov, Grigorii Eremeevich Evdokimov, Klavdia Ivanovna Nikolaeva and others.[43]

There was also a Women's List (no. 13).[2] |

Petrograd City

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Bolsheviks |

424,027 |

45.00 |

| Kadets |

246,506 |

26.16 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

152,230 |

16.15 |

| Orthodox |

24,139 |

2.56 |

| Popular Socialists |

19,109 |

2.03 |

| Mensheviks (Potresovites)[44] |

17,427 |

1.85 |

| Roman Catholic |

14,382 |

1.53 |

| Menshevik-Internationalists |

11,740 |

1.25 |

| Cossack |

6,712 |

0.71 |

| League of Women Voters |

5,310 |

0.56 |

| Non-Partisan |

4,942 |

0.52 |

| Right-wing Socialist-Revolutionaries |

4,696 |

0.50 |

Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries-

Fareynikte alliance |

4,219 |

0.45 |

| Other religious |

3,797 |

0.40 |

| Unity |

1,823 |

0.19 |

| Radical Democrats |

413 |

0.04 |

| Unaccounted |

861 |

0.09 |

| Total: |

942,333 |

|

|

|

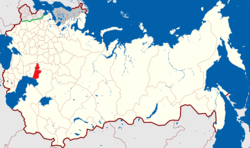

| Moscow City |

Voter turnout in the city was estimated at between 65.4% and 69.7%.[41] |

Moscow City

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Bolsheviks |

366,148 |

47.88 |

| Kadets |

263,859 |

34.50 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

62,260 |

8.14 |

Democratic Socialist Bloc

(incl. Cooperative, Unity) |

35,305 |

4.62 |

| Mensheviks |

19,690 |

2.57 |

| Rightist |

4,085 |

0.53 |

| Popular Socialists |

2,508 |

0.33 |

| Ukrainian Bloc-National Bloc alliance |

2,346 |

0.31 |

| Commercial-Industrial |

2,300 |

0.30 |

| Peasants Union |

2,279 |

0.30 |

| Germans |

2,076 |

0.27 |

| Menshevik-Internationalists |

1,907 |

0.25 |

| Total: |

764,763 |

|

|

|

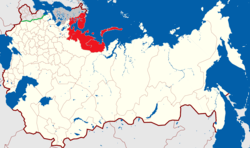

Archangel

|

Radkey's account is missing 4 uezds, representing some 25% of the electorate the Archangel electoral district.[45] Notably, Archangel had a different electoral system than the rest of the country, as voters voted for individual candidates rather than party lists.[45] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Ivanov |

SR |

| Kvyatkovskiy |

SR |

|

Olonets

|

Olonets had special electoral system, electing 2 deputies and with each voter having 2 votes. Radkey's summary excludes 126,827 duplicate votes. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks had an electoral alliance, with each of the two parties presenting one candidate. Both were elected with big margins, SR candidate obtained 127,062 whilst the Menshevik candidate obtained 126,827 votes.[46] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Matveev |

SR-Menshevik bloc |

| Shishkin |

SR-Menshevik bloc |

|

Vologda

|

Out of the 10 uezds in Vologda electoral district, Radkey's account has 1 uezds with a largely incomplete vote count and gaps in coverage in another 2 uezds. In Vologda the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks had a common list.[47] Soviet sources indicated that Social Democratic list was dominated by the Bolsheviks.[48] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Galkin |

SR |

| Koryakin |

SR |

| Maslov |

SR |

| Raschesaev |

SR |

| Sorokin |

SR |

| Yuretsky |

SR |

| Vetoshkin |

Bolshevik |

| Cheranovsky |

Ukrainian SR |

|

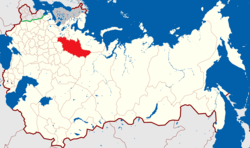

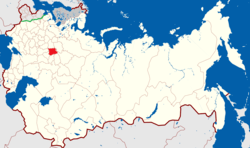

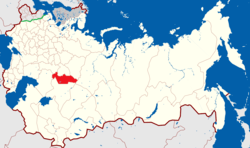

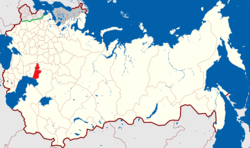

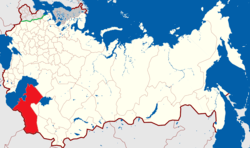

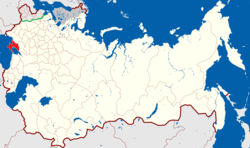

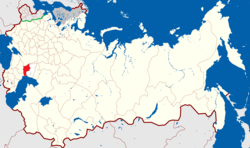

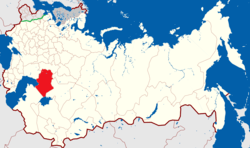

Petrograd Province

_Electoral_District_-_Russian_Constituent_Assembly_election%2C_1917_(12).png) |

According to Radkey the result is incomplete, as data is missing for 7 minor lists.[49] |

|

|

Pskov

|

Out of 13 lists that were submitted to the electoral authorities, 4 were barred from contesting.[50] The SR list was dominated by Left SR elements.[51] A priest was killed in connection with the election day, one of few violent incidents across the country.[52] |

Pskov

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

295,012 |

57.25 |

| Bolsheviks |

173,631 |

33.69 |

| Kadets |

25,961 |

5.04 |

| Mensheviks |

4,870 |

0.95 |

| Popular Socialists |

4,059 |

0.79 |

| Lettish Radical Democrats |

3,859 |

0.75 |

| Landowners |

3,209 |

0.62 |

| League of Women Voters |

2,366 |

0.46 |

| Non-Partisan |

2,337 |

0.45 |

| Total: |

515,304 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Bekleshov |

SR |

| Olkhin |

SR |

| Pokrovsky |

SR |

| Safonov |

SR |

| Utkin |

SR |

| Joffe |

Bolshevik |

| Usharnov |

Bolshevik |

| Yurov (Okhotin) |

Bolshevik |

|

Novgorod

|

Whilst Novgorod was an agrarian province, the Bolsheviks obtained a good vote. This might have been due to the fact that many inhabitants were accustomed to perform seasonal work in nearby Petrograd.[53] 4 local peasants lists did not qualify to run in the election.[50] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Gukovsky |

SR |

| Kobyakov |

SR |

| Leontiev |

SR |

| Sokolov |

SR |

| Ermakov |

Bolshevik |

| Pashin |

Bolshevik |

| Trotsky |

Bolshevik |

| Uritsky |

Bolshevik |

| Valentinov |

Bolshevik |

|

Estonia

|

The Bolsheviks and Estonian Labour Party had their strongest support in Reval and northern Estonia. Bolsheviks obtained 47.6% of the votes cast in Reval. The Democratic Bloc obtained 53.4% in Tartu, and did also get a good number of votes in southern Estonia.[54] Notably, the Bolsheviks benefited from popular discontent with the failure of the Provisional Government to follow through on its promises of self-determination for Estonia.[54] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Anvelt |

Bolshevik |

| Pöögelmann |

Bolshevik |

| Rabchinsky |

Bolshevik |

| Vakmann |

Bolshevik |

| Seljamaa |

Estonian Labour |

| Vilms |

Estonian Labour |

| Poska |

Estonian Democratic |

| Tõnisson |

Estonian Democratic |

|

Livonia

|

Latvia was a Bolshevik stronghold at the time, as only in Latvia did the Social Democrats continue to function as a political party following the waves of repression 1905-1908.[55] After the February Revolution, the political scene in Riga was similar to that of many other cities in Russia, with Bolsheviks becoming the dominant force in the soviets and competing for power with the moderate socialists and the city duma. By May 1917 the Bolsheviks had emerged as the main political force of Latvian Riflemen's soviet. Gradually the Bolsheviks began to dominate Riga, but on September 3, 1917 German troops seized control of the city.[56] In September 1917 the Bolsheviks had some 12,000 members in Latvia, the Mensheviks 2,600.[55]

97,781 votes (72%) were cast for Social-Democracy of the Latvian Territory, the Bolshevik affiliate organization in Latvia.[57] At the time Riga was under German occupation so no vote took place there. In 9 uezds some 9,000 votes are missing according to Radkey.[58] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Goldmanis |

Lettish Peasant Union |

| Bērziņš |

SD of Latvian Territory |

| Peterson |

SD of Latvian Territory |

| Rozin |

SD of Latvian Territory |

|

Vitebsk

|

White Russian separatism was a negligible force in the electoral district.[59] Grigorii (Zvi Hirsh) Bruk, Zionist and former Kadet deputy of the First Duma, stood as candidate of the Jewish National Electoral Committee.[60] |

Vitebsk

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Bolsheviks |

287,101 |

51.22 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

150,279 |

26.81 |

| Lettish Socialist Federalist |

26,990 |

4.82 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

24,790 |

4.42 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

12,471 |

2.22 |

| Polish Nationalist |

10,556 |

1.88 |

| Peasants of Vitebsk Province |

9,752 |

1.74 |

| White Russians |

9,019 |

1.61 |

| Kadets |

8,132 |

1.45 |

| Landowners |

6,098 |

1.09 |

| Lettish Nationalist |

5,881 |

1.05 |

| Letgallian Nationalist |

5,118 |

0.91 |

| Popular Socialists |

3,599 |

0.64 |

| Peasants of Boletskii Volost |

752 |

0.13 |

| Total: |

560,538 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Boldysh |

SR |

| Bulat |

SR |

| Gizetti |

SR |

| Ceshejko-Sochacki |

Bolshevik |

| Dzerzhinsky |

Bolshevik |

| Kamenev |

Bolshevik |

| Pinson |

Bolshevik |

| Rivkin |

Bolshevik |

| Ryvkin |

Bolsheviks |

| Sarkisyants |

Bolshevik |

|

Minsk

|

White Russian separatism was a negligible force in the electoral district.[59] The conservative press reported a quiet and orderly election in the province.[61] According to Radkey, his count of the result in Minsk is largely complete, only lacking 3 out of 25 volosts Mozyr uezd. These 3 volosts had 16,755 eligible voters.[58] |

Minsk

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Bolsheviks |

579,087 |

63.13 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

181,673 |

19.81 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

65,046 |

7.09 |

| Polish |

36,882 |

4.02 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

16,277 |

1.77 |

| Kadets |

10,724 |

1.17 |

| Radical Democrats |

10,040 |

1.09 |

| Jewish Soc.-Dem. Labour Party (Poalei Zion) |

6,184 |

0.67 |

| Fareynikte |

4,880 |

0.53 |

| Landowners |

3,465 |

0.38 |

| Gromada |

2,998 |

0.33 |

| Total: |

917,256 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Balay |

SR |

| Drizo |

SR |

| Gamzagurdi |

SR |

| Nesterov |

SR |

| Brutzkus |

Jewish National Electoral Committee |

| Alibekov |

Bolshevik |

| Freiman |

Bolshevik |

| Gromashevsky |

Bolshevik |

| Kozhuro |

Bolshevik |

| Krivoshein |

Bolshevik |

| Lander |

Bolshevik |

| Schlegel |

Bolshevik |

| Seleznev |

Bolshevik |

| Taganov |

Bolshevik |

|

Mogilev

|

According to Radkey the vote count in Mogilev is largely incomplete. He claims to have the data for Gomel (with the votes for all 11 lists), Mogilev (with votes for the 7 most voted lists) and Orsha (with votes for the 6 most votes lists) towns as well as 80 precincts in Gomel uezd (but in these precincts, only the vote for SR and Bolshevik lists).[58] The SRs benefited from the fact that the leader heading the Mogilev Provincial Soviet of Peasants Deputies was largely popular in the province.[62] |

Mogilev

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

50,684 |

37.55 |

| Bolsheviks |

28,446 |

21.07 |

| Kadets |

14,494 |

10.74 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

14,101 |

10.45 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

10,549 |

7.81 |

| Jewish Soc.-Dem. Labour Party (Poalei Zion) |

7,900 |

5.85 |

| Polish |

4,635 |

3.43 |

| Fareynikte |

1,583 |

1.17 |

| White Russians |

1,385 |

1.03 |

| Landowners |

293 |

0.22 |

| Unaccounted |

924 |

0.68 |

| Total: |

134,994 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Buslov |

SR |

| Khrisanenkov |

SR |

| Kovarsky |

SR |

| Maleev |

SR |

| Malyshitsky |

SR |

| Rappoport |

SR |

| Shishaev |

SR |

| Tsvetaev |

SR |

| Vasilevsky |

SR |

| Voronov |

SR |

| Zakrevsky |

SR |

| Zasorin |

SR |

| Kaganovich |

Bolshevik |

| Leplevsky |

Bolshevik |

| Friedman |

Jewish National Committee |

| Mazeh |

Jewish National Committee |

|

Smolensk

|

2 volost-level lists were barred from participating in the election.[50] List no. 3, endorsed by Smolensk Provincial Council of SR Party and the Smolensk Provincial Congress of Peasants Deputies, was headed by E.K. Breshko-Breshkovskaia and Andrei Argunov.[63] |

|

|

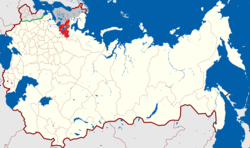

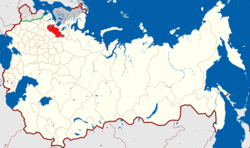

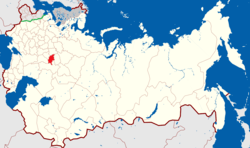

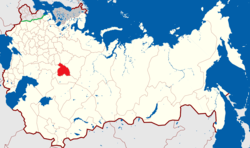

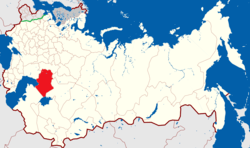

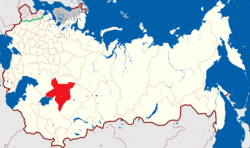

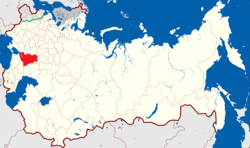

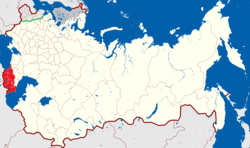

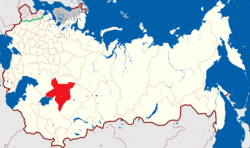

Moscow Province

_Electoral_District_-_Russian_Constituent_Assembly_election%2C_1917.png) |

According to Radkey's account, only few votes are missing from the summary (one military voting box in Moscow uezd, the votes from a single volost in Bronnitsy uezd and the votes for smaller parties in Serpukhov uezd).[58] |

Moscow Province

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

Bolsheviks-

Menshevik-Internationalists |

351,853 |

56.43 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

159,630 |

25.60 |

| Kadets |

43,295 |

6.94 |

| Mensheviks |

27,108 |

4.35 |

| Peasant Union |

12,967 |

2.08 |

| Rightist |

8,443 |

1.35 |

| Old Believer |

7,467 |

1.20 |

| Popular Socialists |

6,058 |

0.97 |

| Non-Partisan |

4,497 |

0.72 |

| Landowners |

2,189 |

0.35 |

| Total: |

623,507 |

|

|

|

Tver

|

Radkey lists the Tver result as 'somewhat incomplete'.[64] Russkoe Slovo reported that the election was conducted orderly, whilst SR organ Delo Naroda stated that Bolsheviks disrupted the polls in Rzhev uezd.[61] A farmer list was denied contesting the election in Tver.[50] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Tikhomirov |

SR |

| Tolmachevsky |

SR |

| Volsky |

SR |

| Arosev |

Bolshevik |

| Bulatov |

Bolsheviks |

| Medov |

Bolshevik |

| Schmidt |

Bolshevik |

| Sokolnikov |

Bolshevik |

| Vagzhanov |

Bolshevik |

|

Yaroslavl

|

|

|

|

Kostroma

|

Out 15 lists submitted, 5 were rejected by the electoral authorities.[50] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Kondratiev |

SR |

| Kozlov |

SR |

| Lotoshnikov |

SR |

| Maltsev |

SR |

| Danilov |

Bolshevik |

| Larin-Lurie |

Bolshevik |

| Malyutin |

Bolshevik |

| Rostopchin |

Bolshevik |

|

Vladimir

|

Vladimir was heavily industrialized, second only to Moscow itself. There were many textile mills in Ivanovo-Voznesensky, Out of 13 uezd, SR won in 2; Viazniki (east of industrial belt), an area with hemp and linen production where SRs scored 42,4%, and further east in Gorokhovets uezd, an area with no factories where SRs scored 57.4%.[53]) Out of 11 lists submitted, 7 were approved whilst 4 non-partisan peasants' lists were denied registration.[50] |

|

|

Kaluga

|

In Kaluga, the SR list was dominated by leftist elements.[39] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Borodachov |

SR |

| Eliseev |

SR |

| Parol |

SR |

| Ginzburg |

Bolshevik |

| Glebov-Avilov |

Bolshevik |

| Logachev |

Bolshevik |

| Stukov |

Bolshevik |

| Zakharov |

Bolshevik |

|

Tula

|

The votes from the city of Tula and 10 out 12 uezds are complete, according to Radkey. The votes from Efremov uezd and one of the volosts of Odoev uezd are not covered in Radkey's account.[58] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Arvatov |

SR |

| Gurevich |

SR |

| Medvedev |

SR |

| Nearonov |

SR |

| Kaminsky |

Bolshevik |

| Kaul |

Bolshevik |

| Kolesnikov |

Bolshevik |

| Yakovleva |

Bolshevik |

|

Riazan

|

Radkey's account is missing the vote from Egoriev uezd, 1 out of 12 uezds in the electoral district.[58] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Barinov |

SR |

| Gendelman |

SR |

| Govorov |

SR |

| Pavlov |

SR |

| Sorokin |

SR |

| Sukharev |

SR |

| Gorshkov |

Bolshevik |

| Osinsky |

Bolshevik |

| Sereda |

Bolshevik |

| Voronkov |

Bolshevik |

|

Orel

|

The Kraiskovo electoral commission chair was killed by soldiers at the time of the election.[61] |

Orel

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

511,049 |

62.70 |

| Bolsheviks |

241,786 |

29.66 |

| Kadets |

18,345 |

2.25 |

| Mensheviks |

16,301 |

2.00 |

| Landowner |

12,911 |

1.58 |

| Commercial-Industrial |

4,462 |

0.55 |

Rightwing Socialist Bloc

(Popular Socialists, Cooperative, Unity) |

1,384 |

0.17 |

| Home Owners |

438 |

0.05 |

| Unaccounted |

8,453 |

1.04 |

| Total: |

815,129 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Bukin |

SR |

| Goncharov |

SR |

| Khodotov |

SR |

| Maslov |

SR |

| Matveevskaya |

SR |

| Vladykin |

SR |

| Volnov |

SR |

| Volodin |

SR |

| Andreev |

Bolshevik |

| Fokin |

Bolshevik |

| Ivanov |

Bolshevik |

| Kuznetsov |

Bolshevik |

|

Kursk

|

Kursk was an agrarian, black-earth province with no industries. The Bolshevik vote was attributed to soldiers returning home from the front. [65] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Baryshnikov |

SR |

| Belosov |

SR |

| Doroshev |

SR |

| Kholodov |

SR |

| Kutepov |

SR |

| Merkulov |

SR |

| Neruchev |

SR |

| Pakhomov |

SR |

| Piyanich |

SR |

| Romanenko |

SR |

| Rusanov |

SR |

| Vlasov |

SR |

| Ozemblovsky |

Bolshevik |

|

Voronezh

|

8 out of 16 lists submitted were disqualified from contesting.[50] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Kardashov |

Bolshevik |

| Nevsky |

Bolshevik |

| Antipin |

SR |

| Bliznyuk |

SR |

| Burevoy-Soplyakov |

SR |

| Gladkikh |

SR |

| Khrenovsky |

SR |

| Kogan-Bernstein |

SR |

| Mamkin |

SR |

| Nikitin |

SR |

| Oganovsky |

SR |

| Perveeva |

SR |

| Postnikov |

SR |

| Smirnov |

SR |

| Zinin |

SR |

|

Tambov

|

73% electoral participation was reported, as the SRs had a good mobilization capacity among the peasantry. [66] In the Spassko-Kashminskaia canton, Morshansk uezd the SR local government banned the Bolshevik election campaign, alleging that the Bolsheviks were German spies. [67] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Batmanov |

SR |

| Bobynin |

SR |

| Chernov |

SR |

| Chernyshov |

SR |

| Ilyin |

SR |

| Kiselev |

SR |

| Kondratenkov |

SR |

| Merkulov |

SR |

| Nabatov |

SR |

| Nemtinov |

SR |

| Odintsov |

SR |

| Ryabov |

SR |

| Sletenova-Chernova |

SR |

| Volsky |

SR |

| Moiseev |

Bolshevik |

| Olminsky |

Bolshevik |

| Schlichter |

Bolshevik |

|

Penza

|

5 out of 11 submitted lists were disqualified (and some additional lists submitted their lists too late to register).[50] In Penza town there were 49,741 eligible voters, out of whom 17,583 voted (35%).[41] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Avksentiev |

SR |

| Boldov |

SR |

| Fedorovich |

SR |

| Gots |

SR |

| Konogov |

SR |

| Kostin |

SR |

| Leutnov |

SR |

| Prokhorov |

SR |

| Tsyngovatov |

SR |

|

Nizhni Novgorod

|

Only in the Nizhni Novgorod constituency could the combined forces of clergy and far right make an electoral impact. [68]The Christian Union for Faith and Fatherland had a relative success. [69] |

Nizhni Novgorod

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

314,004 |

54.15 |

| Bolsheviks |

133,950 |

23.10 |

| Christian Union for Faith and Fatherland |

48,428 |

8.35 |

| Kadets |

34,726 |

5.99 |

| Turkic-Tatar |

19,935 |

3.44 |

| Old Believer |

16,230 |

2.80 |

| Mensheviks |

7,634 |

1.32 |

| Popular Socialists |

2,666 |

0.46 |

| Ukrainian Bloc |

126 |

0.02 |

| Unaccounted |

2,198 |

0.38 |

| Total: |

579,897 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Sergius |

Christian Unity |

| Fokeev |

SR |

| Kutuzov |

SR |

| Lukyanov |

SR |

| Rakov |

SR |

| Sumgin |

SR |

| Tyurikov |

SR |

| Danilov |

Bolshevik |

| Romanov |

Bolshevik |

|

Simbirsk

|

Electoral participation was reported at around 58%.[41] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Sverdlov |

Bolshevik |

| Almazov |

SR |

| Gavronsky |

SR |

| Moshkin |

SR |

| Petrov |

SR |

| Pochekuev |

SR |

| Titov |

SR |

| Vorobiev |

SR |

| Tsalikov |

Muslim Shuro |

|

Kazan

|

66% turnout was reported.[41] The Chuvash largely voted for the SRs, and the local SR party branch was dominated by leftist elements. [70]The Tatars voters were split between leftist and rightist lists. [71] |

Kazan

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

264,158 |

30.77 |

| Chuvash |

226,496 |

26.38 |

| Muslim Socialists |

153,151 |

17.84 |

| Tatar Rightwing |

99,080 |

11.54 |

| Bolsheviks |

51,936 |

6.05 |

| Kadets |

31,728 |

3.70 |

| Orthodox |

12,322 |

1.44 |

| Rightwing Socialist-Revolutionaries |

9,820 |

1.14 |

| Mensheviks |

4,906 |

0.57 |

| Popular Socialists-Cooperative alliance |

2,993 |

0.35 |

| Landowner-Middle Class alliance |

2,001 |

0.23 |

| Total: |

858,591 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Alyunov |

Chuvash |

| Nikolaev |

Chuvash |

| Vasiliev |

Chuvash |

| Alkin |

Muslim Socialist List |

| Waxitov |

Muslim Socialist List |

| Kolegaev |

SR |

| Martyushin |

SR |

| Mayorov |

SR |

| Mokhov |

SR |

| Sukhanov |

SR |

| Khalfin |

Muslim Assembly |

| Salekhov |

Muslim Assembly |

|

Samara

|

Electoral turnout at 54.86%.[41] Out of 95 different lists submitted, 79 turned down (out of which approx 42 due to late submission).[50] The constituency had large German and Tatar minorities. [72] In Samara city the Bolsheviks polled 42% of the vote, the SRs 27% and Kadets 14%.[14] |

Samara

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 3 - Socialist-Revolutionaries |

702,924 |

58.47 |

| List 2 - Bolsheviks |

179,533 |

14.93 |

| List 13 - Muslim Shuro |

126,558 |

10.53 |

List 16 - Union of Russian Citizens of

German Nationality in the Central Volga Region |

47,705 |

3.97 |

| Kadets |

44,466 |

3.70 |

List 1 - Union of Socialists of

the Volga German Region |

42,148 |

3.51 |

| Orthodox |

13,133 |

1.09 |

| Bashkirs |

12,397 |

1.03 |

| Chuvash |

9,036 |

0.75 |

| Old Believer |

6,508 |

0.54 |

| Ukrainian Bloc |

4,378 |

0.36 |

| Popular Socialists |

4,364 |

0.36 |

| Mensheviks |

4,166 |

0.35 |

| Peasants |

3,030 |

0.25 |

| Unity |

937 |

0.08 |

| Menshevik-Internationalists |

936 |

0.08 |

| Total: |

1,202,219 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Mukhamediyarov |

Muslim Shuro |

| Tuktarov |

Muslim Shuro |

| Ermoshchenko |

Bolshevik |

| Kuybyshev |

Bolshevik |

| Maslennikov |

Bolshevik |

| Arkangelsky |

SR |

| Bashkirov |

SR |

| Belozerov |

SR |

| Brushvit |

SR |

| Chupakhin |

SR |

| Dedusenko |

SR |

| Elyashevich |

SR |

| Fortunatov |

SR |

| Klimushkin |

SR |

| Lazarev |

SR |

| Maslov |

SR |

| Bogoslovov |

SR |

|

Saratov

|

Saratov had been one of the early strongholds of the SRs. [73] Kerensky was one of the SR candidates, but many voters scratched his name from the list (and thus made their votes invalid). [6] was politically turbulent, also during the election. [6] In Saratov Bolshevik campaigners were frequently attacked by rich farmers.[67] Whilst the SR won in the largely agrarian district, the Bolsheviks had a strong showing, with strong support from soldiers and from the industrial city of Tsaritsyn.[61] Khvalynsk uezd was an Old Believer stronghold, with presence of Khlysty and Skoptsky sects. [74]

The German socialists didn't field a list in Saratov, whilst the German Central Committee contested on the Volga German List 7.[75] |

Saratov

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 12 - Socialist-Revolutionaries |

612,094 |

56.28 |

| List 10 - Bolsheviks |

261,308 |

24.03 |

List 3 - Union of Ukrainian and Tatar

SR Peasant Organizations List |

53,445 |

4.91 |

| List 7 - Volga Germans |

50,025 |

4.60 |

| List 1 - Kadets |

27,226 |

2.50 |

| List 5 - Orthodox People's |

17,414 |

1.60 |

| List 2 - Mensheviks |

15,152 |

1.39 |

| List 4 - Old Believer |

13,956 |

1.28 |

| List 6 - Union of Landowners |

13,804 |

1.27 |

| List 8 - Popular Socialists |

10,243 |

0.94 |

| List 9 - Society for Faith and Order |

6,600 |

0.61 |

| List 11 - Peasants of Petrovsk uezd and Mordva |

6,379 |

0.59 |

| Total: |

1,087,646 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Antonov |

Bolshevik |

| Milutin |

Bolshevik |

| Minin |

Bolshevik |

| Vasiliev |

Bolshevik |

| Bykhovsky |

SR |

| Chernavin |

SR |

| Chernenkov |

SR |

| Kerensky |

SR |

| Kotov |

SR |

| Minin |

SR |

| Panchurin |

SR |

| Rakitnikov |

SR |

| Ulyanov |

SR |

| Ustinov |

SR |

| Zatonsky |

SR |

|

Astrakhan

|

Radkey's account is incomplete, with some votes missing.[39] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Usmanov |

Muslim |

| Tereshchenko |

SR |

| Trusov |

Bolshevik |

| Figner |

SR |

| Nezhintsev |

SR |

|

Viatka

|

8 out of 20 submitted lists were disqualified.[50] Cheremis ran on a joint list with the Popular Socialists. [76] Radkey's account only includes full result for 3 lists (Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Orthodox), albeit the number of votes for the Orthodox list has been rounded off. The real vote of the other nine lists, according to Radkey, would have been more than double that what is accounted for.[58] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Pastukhov |

Bolshevik |

| Popov |

Bolshevik |

| Shvetsov |

Bolshevik |

| Sponde |

Bolshevik |

| Biryukov |

SR |

| Buzanov |

SR |

| Efremov |

SR |

| Evseev |

SR |

| Golovizin |

SR |

| Kropotov |

SR |

| Kuznetsov |

SR |

| Salamatov |

SR |

| Shulakov |

SR |

| Zbarsky |

SR |

| Yambaev |

Muslim Congress |

| Tchaikovsky |

Popular Socialists-Cheremi National Union alliance |

| Vikhlyaev |

SR |

|

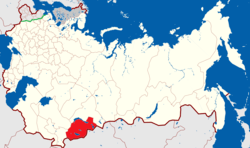

Perm

|

The Peasants Union, with more than 13,000 votes, was mainly based in Krasnoufimsk uezd. [72] |

Perm

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

665,118 |

52.05 |

| Bolsheviks |

268,292 |

20.99 |

| Kadets |

111,241 |

8.71 |

| Orthodox |

47,881 |

3.75 |

| Turkic-Tatar |

47,578 |

3.72 |

| Old Believer |

35,853 |

2.81 |

| Tatar Rightwing |

29,683 |

2.32 |

Rightwing Socialist Bloc

(Right SRs, Popular Socialists and Unity) |

29,112 |

2.28 |

| Mensheviks |

28,002 |

2.19 |

| Peasants Union |

13,748 |

1.08 |

| Radical Democrats |

1,381 |

0.11 |

| Total: |

1,277,889 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Alekseev |

SR |

| Bondarev |

SR |

| Gerstein |

SR |

| Kabakov |

SR |

| Kuznetsov |

SR |

| Sigov |

SR |

| Tarabukin |

SR |

| Varushkin |

SR |

| Zateeyshchikov |

SR |

| Zdobnov |

SR |

| Zisman |

SR |

| Krol |

Kadet |

| Sumarokov |

Kadet |

| Andronnikov |

Bolshevik |

| Beloborodov |

Bolshevik |

| Krestinsky |

Bolshevik |

| Sosnovsky |

Bolshevik |

| Tukhvatullin |

Bashkir-Tatar group |

|

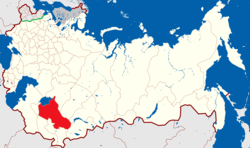

Ufa

|

Ufa was a multinational constituency. [72]The SR list was dominated by leftist elements.[39] |

Ufa

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

322,166 |

33.68 |

| Muslim Socialists |

304,864 |

31.88 |

| Bashkir |

135,977 |

14.22 |

| Tatar Rightwing |

88,850 |

9.29 |

| Bolsheviks |

48,151 |

5.03 |

| Kadets |

15,825 |

1.65 |

| Orthodox |

11,178 |

1.17 |

| Popular Socialists |

11,429 |

1.19 |

| Landowner |

7,358 |

0.77 |

| Cooperative |

4,941 |

0.52 |

| Peasants |

3,078 |

0.32 |

| Mensheviks |

2,614 |

0.27 |

| Total: |

956,431 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Teregulov |

Muslim National Council |

| Kuvatov |

Bashkir Federalist |

| Validov |

Bashkir Federalist |

| Akhmerov |

Council of Peasants' Deputies |

| Ibragimov |

Council of Peasants' Deputies |

| Ilyasov |

Council of Peasants' Deputies |

| Mukhametdinov |

Council of Peasants' Deputies |

| Syuncheley |

Council of Peasants' Deputies |

| Brillantov |

SR |

| Filatov |

SR |

| Osintsev |

SR |

| Steinberg |

SR |

| Trutovsky |

SR |

|

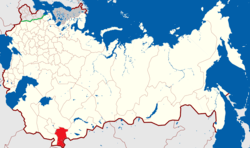

Orenburg

|

According to Radkey, his account of the Bashkir Federalist vote is underestimated, believing that the real figure would land at around 100,000.[69] |

Orenburg

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Bolsheviks |

163,425 |

24.14 |

| Orenburg Cossack Host |

144,039 |

21.28 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

110,172 |

16.28 |

| Bashkir |

51,787 |

7.65 |

| Kadets |

24,757 |

3.66 |

| Turkic-Tatar |

16,652 |

2.46 |

| Mensheviks |

7,544 |

1.11 |

| Cooperative |

7,296 |

1.08 |

| Popular Socialists |

5,681 |

0.84 |

| Unaccounted |

145,512 |

21.50 |

| Total: |

676,865 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Dutov |

Cossack |

| Krivoschekov |

Cossack |

| Matushkin |

Cossack |

| Myakutin |

Cossack |

| Bogdanov |

Cossack |

| Polyakov |

SR |

| Sorokin |

SR |

| Chutskaya |

Bolshevik |

| Korostelev |

Bolshevik |

| Zwilling |

Bolshevik |

| Bikbov |

Bashkir Federalist |

| Fakhretdinov |

Bashkir Federalist |

| Manatov |

Bashkir Federalist |

|

Kiev

|

Kiev was a historical Black Hundred stronghold, and monarchists got some 3% of the votes in the district. [77] |

Kiev

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Ukrainian Bloc |

1,161,033 |

77.26 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

90,829 |

6.04 |

| Bolsheviks |

60,693 |

4.04 |

| Rightist |

48,758 |

3.24 |

| Polish |

42,943 |

2.86 |

| Kadets |

21,667 |

1.44 |

| Bund |

20,144 |

1.34 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

19,220 |

1.28 |

| Fareynikte |

14,115 |

0.94 |

| Mensheviks |

11,613 |

0.77 |

| Poalei Zion |

4,086 |

0.27 |

| USF-Popular Socialists alliance |

3,072 |

0.20 |

| Landowner-Middle Class alliance |

2,508 |

0.17 |

| Unity |

928 |

0.06 |

| Peasants |

655 |

0.04 |

| Non-Partisan |

203 |

0.01 |

| Other |

258 |

0.02 |

| Total: |

1,502,725 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Chechel |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Darchuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Donchenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Dragomiretsky |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Hrushevsky |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Ilchenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Khimerik |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Khomutovsky |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Kotik |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Mandryka |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Porsh |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Prisyazhnyuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Pyrkovka |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Rohmanyuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Sevryuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Shvets |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Stasyuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Tkachenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Vynnychenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Fyalek |

Bolshevik |

| Syrkin |

Jewish National Committee |

|

Volynia

|

17 submitted lists rejected, out of which 5 were peasants' lists.[50] The western parts of the electoral district were under German or Austrian occupation.[58] Radkey expresses concern that the votes account from Volynia (exclusively brought from the 1918 study by Sviatitski) may have been largely incomplete, possibly an effect of the proximity to the battle lines.[58] |

Volynia

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries |

569,044 |

70.76 |

| Polish |

57,998 |

7.21 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

55,967 |

6.96 |

| Bolsheviks |

35,612 |

4.43 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

27,575 |

3.43 |

| Kadets-Peasant alliance |

22,337 |

2.78 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

16,947 |

2.11 |

| Orthodox |

1,438 |

0.18 |

| Fareynikte |

? |

|

| Poalei Zion |

? |

|

| Ukrainian Socialist-Federalists |

? |

|

| Unaccounted |

17,290 |

2.15 |

| Total: |

804,208 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Gedz |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kobylchuk |

Ukrainian SR |

| Koval |

Ukrainian SR |

| Marcyniuk |

Ukrainian SR |

| Ovsyanik |

Ukrainian SR |

| Pavlyuk |

Ukrainian SR |

| Trots |

Ukrainian SR |

| Lipkovsky |

Polish List |

|

Podolia

|

Podolia was close to the frontline. [78] Radkey cites that the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party organ Robitchna Gazeta reported that elections were held in Podolia between Dec 3-7, and presented results from 9 out of 12 uezds, but Robitchna Gazeta's party tally greater than the vote cast in the 9 uezds, possibly pointing to results included from the remaining 3 uezds.[78] The conservative Russkoe Slovo reported normal voting conditions in Podolia.[61] |

Podolia

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Ukrainian Bloc |

652,306 |

78.57 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

62,869 |

7.57 |

| Polish |

46,912 |

5.65 |

| Bolsheviks |

27,540 |

3.32 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

10,170 |

1.22 |

| Bund |

7,959 |

0.96 |

| Kadets |

7,951 |

0.96 |

| Mensheviks |

4,028 |

0.49 |

| Ukrainian Toilers List |

3,810 |

0.46 |

| Fareynikte |

3,415 |

0.41 |

| Poalei Zion |

2,164 |

0.26 |

| Popular Socialists |

852 |

0.10 |

| Other |

284 |

0.03 |

| Total: |

830,260 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Antonovych |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Blonski |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Dudich |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Dyachuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Gerasimenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Golovchuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Grigoriev |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Isaevich |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Litvitsky |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Liubynsky |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Machushenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Nikolaychuk |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Shevchenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Shimanovich |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Tkach |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Verkhola |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Widybida-Rudenko |

Ukrainian Bloc |

| Bartoszewicz |

Polish List |

|

Chernigov

|

Chernigov was an agrarian province. The Bolshevik Party was absent in most uezds and weak in others. But returning soldiers, about a quarter of the electorate, boosted the Bolshevik vote. [79] |

Chernigov

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries |

484,456 |

49.76 |

| Bolsheviks |

271,174 |

27.85 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

105,565 |

10.84 |

| Kadets |

28,864 |

2.96 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

28,308 |

2.91 |

| Ukrainian Non-Partisans |

12,650 |

1.30 |

| Landowners |

11,810 |

1.21 |

| Mensheviks |

10,813 |

1.11 |

Ukrainian Socialist-Federalists-

Popular Socialists alliance |

10,089 |

1.04 |

| Old Believer |

4,858 |

0.50 |

| Poalei Zion |

2,808 |

0.29 |

| Non-Partisans |

1,005 |

0.10 |

| Peasants |

911 |

0.09 |

| Commercial-Industrial |

335 |

0.03 |

| Total: |

973,646 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Breshko-Breshkovskaya |

SR |

| Kostenetsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kovalevsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kovbasa |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kuzmenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Lashkevich |

Ukrainian SR |

| Odinets |

Ukrainian SR |

| Sayenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Shapoval |

Ukrainian SR |

| Shrag |

Ukrainian SR |

| Bosch |

Bolshevik |

| Motorra |

Bolshevik |

| Pyatakov |

Bolshevik |

| Ryndich |

Bolshevik |

|

Poltava

|

Poltava was an agrarian province . [80]Voter turnout was reported at 74%.[41] The Russian SRs (dominated by the left) ran a joint list with the Ukrainian SRs (dominated by Left) [81]The Selianska Spilka ('Village Union'), the agrarian wing of the Ukrainian SR, confronted the Farmers (Landowners) Party, excluding Landowners from local election commissions. The campaign against the Landowners Party occasional took violent shape.[80] |

Poltava

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 8 - Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries |

727,247 |

63.28 |

List 17 - Socialist-Revolutionaries-

Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries alliance |

198,437 |

17.27 |

| Bolsheviks |

64,460 |

5.61 |

| List 2 - Farmer-Owners |

61,115 |

5.32 |

| Ukrainian Social Democrats |

22,613 |

1.97 |

| Kadets |

18,105 |

1.58 |

| Jewish National Committee |

13,722 |

1.19 |

| Jewish List |

12,100 |

1.05 |

| Ukrainian Socialist-Federalists |

9,092 |

0.79 |

| Folkspartey |

6,448 |

0.56 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

5,993 |

0.52 |

| Popular Socialists-Cooperative alliance |

4,391 |

0.38 |

| List without title |

1,657 |

0.14 |

| Fareynikte |

1,482 |

0.13 |

| Ukrainian National Republican |

1,070 |

0.09 |

| Poalei Zion |

879 |

0.08 |

| Local peasant soviet |

445 |

0.04 |

| Total: |

1,149,256 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Kovalyov |

Ukrainian SR-SR alliance |

| Poloz |

Ukrainian SR-SR alliance |

| Terletsky |

Ukrainian SR-SR alliance |

| Galagan |

Ukrainian SR |

| Ivchenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kovalenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kovalevsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Kulichenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Petrenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Polotsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Semenyaga |

Ukrainian SR |

| Sten'ka |

Ukrainian SR |

| Stepanenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Yanko |

Ukrainian SR |

|

Kharkov

|

The SR list in Kharkov was dominated by the left-wing, contesting jointly with the Ukrainian SRs. The rightwing pro-war SR faction had its own list, headed by E.K. Breshko-Breshkovskaia. [82] The Bolsheviks won the election in Kharkov city. [82] |

Kharkov

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

Socialist-Revolutionaries-

Ukrainian SRs alliance |

796,552 |

72.86 |

| Bolsheviks |

114,743 |

10.49 |

| Kadets |

58,302 |

5.33 |

| Rightwing SRs |

42,329 |

3.87 |

| Landowners |

13,847 |

1.27 |

| Menshevik-Internationalists |

12,192 |

1.12 |

| Popular Socialists |

11,852 |

1.08 |

| Orthodox |

10,479 |

0.96 |

| Commercial-Industrial |

6,493 |

0.59 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

6,366 |

0.58 |

| Mensheviks |

6,024 |

0.55 |

| Germans |

5,221 |

0.48 |

| Ukrainian Middle Class |

3,776 |

0.35 |

| Unity |

2,293 |

0.21 |

| Fareynikte |

917 |

0.08 |

| Poalei Zion |

875 |

0.08 |

| Peasants |

530 |

0.05 |

| Rightwing Socialist Bloc |

530 |

0.05 |

| Total: |

1,093,321 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Muranov |

Bolshevik |

| Sergeyev |

Bolshevik |

| Alekseev |

SR |

| Dyakonov |

SR |

| Kachinsky-Oreshin |

SR |

| Karelin |

SR |

| Kravchenko |

SR |

| Mikhailichenko |

SR |

| Ovcharenko |

SR |

| Popov |

SR |

| Severov-Odoyevsky |

SR |

| Shkorbatov |

SR |

| Streltsov |

SR |

| Svyatitsky |

SR |

|

Ekaterinoslav

|

Ekaterinoslav was a large province; ethnically and economically diverse. [83] The Ekaterinoslav electoral district recorded the highest vote for a landowners list in the country. List 1 Landowners and Nonpartisan Progressives gathered 26,597 votes (2.2%), and was headed by Mikhail Rodzianko (an Octobrist leader, having served as the presiding officer in the 3rd and 4th Dumas, elected on the Stolypin franchise). [84] The conservative press reported a quiet and orderly election in the province.[61] |

Ekaterinoslav

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries |

556,012 |

46.60 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

231,717 |

19.42 |

| Bolsheviks |

213,163 |

17.87 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

37,032 |

3.10 |

| Kadets |

27,551 |

2.31 |

| Mensheviks |

26,909 |

2.26 |

| Landowner |

26,597 |

2.23 |

| Germans |

25,977 |

2.18 |

Popular Socialists-

Cooperative alliance |

9,496 |

0.80 |

| Greeks |

9,143 |

0.77 |

| Peasant-Orthodox alliance |

8,068 |

0.68 |

| Unity |

7,363 |

0.62 |

| Fareynikte |

5,831 |

0.49 |

| Bund |

4,883 |

0.41 |

| Poalei Zion |

3,307 |

0.28 |

| Total: |

1,193,049 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Gvozdikovsky |

SR |

| Popov |

SR |

| Rosenblum |

SR |

| Socheva |

SR |

| Bachinsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Karpenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Korzh |

Ukrainian SR |

| Mitsyuk |

Ukrainian SR |

| Radomsky |

Ukrainian SR |

| Romanenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Rosin |

Ukrainian SR |

| Storubel |

Ukrainian SR |

| Stromenko |

Ukrainian SR |

| Surgae |

Ukrainian SR |

| Averin |

Bolshevik |

| Lutovinov |

Bolshevik |

| Petrovsky |

Bolshevik |

| Voroshilov |

Bolshevik |

|

Kherson

|

According to Radkey, the Odessa city results appeared complete, the Odessa uezd possibly incomplete, the Kherson uezd having results from 195 out of 223 voting centers, no indication about whether 2 other uezds' results were complete or not. From the remaining 2 uezds the results were missing altogether.[58]

D. Lvovich of Fareynikte elected as SR list candidate.[85] |

Kherson

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

Ukrainian SRs-SRs

-Fareynikte alliance |

266,771 |

42.98 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

86,190 |

13.89 |

| Bolsheviks |

81,826 |

13.18 |

| Ukrainian Soc.-Dem. Labour Party |

63,159 |

10.18 |

| Kadets |

53,770 |

8.66 |

| Germans |

27,879 |

4.49 |

| Mensheviks-Bund |

14,369 |

2.31 |

| Orthodox |

13,038 |

2.10 |

Popular Socialists-

Cooperative alliance |

5,626 |

0.91 |

| Rightist |

4,217 |

0.68 |

| Peasant-Old Believer alliance |

2,188 |

0.35 |

| Poalei Zion |

1,687 |

0.27 |

| Total: |

620,720 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Gruzenberg |

Jewish National Bloc |

| Tyomkin |

Jewish National Bloc |

| Meiendorf |

German |

| Asmolov |

SR |

| Bontzarevich |

SR |

| Eremenchuk |

SR |

| Feofilaktov |

SR |

| Gavrilyuk |

SR |

| Glevenko |

SR |

| Holubovych |

SR |

| Gordievsky |

SR |

| Lvovich |

SR |

| Richter |

SR |

| Trichevsky |

SR |

| Troichuk |

SR |

| Vekhtev |

SR |

| Yuritsin |

SR |

| Velikhov |

Kadet |

| Chekhivsky |

Ukrainian SD |

| Sklyar |

Bolshevik |

|

Bessarabia

|

Radkey's account is substantially incomplete. [86] According to Radkey, only the results from Kishinev and 3 out of 8 uezds could be gathered by scholars.[87] The 5 uezds left out of the count were more populous.[58] 17 lists were in the fray in Bessarabia. The demographics of the district were divided between Rumanians (48%), Ukrainians (20%) and Russians (8%). Among the elected deputies, SR deputies were Jewish or Russian, whilst the peasant soviet deputies were Rumanian.[87]

As per Serge, some 600,000 people took part in the vote, with the Peasant soviet obtaining some 200,000 votes, SRs 200,000 votes, Jewish national list 60,000, Kadets 40,000 and the Moldavian National Party 14,000.[88] |

Bessarabia

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

85,349 |

33.63 |

| Peasants |

69,085 |

27.22 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

28,785 |

11.34 |

Bolsheviks-

Menshevik-Internationalists |

25,569 |

10.07 |

| Kadets |

16,545 |

6.52 |

| Moldovans |

6,643 |

2.62 |

| Landowners |

5,246 |

2.07 |

| Ukrainian Bloc |

4,241 |

1.67 |

| Bund-Mensheviks |

1,438 |

0.57 |

| Popular Socialists? |

376 |

0.15 |

| Germans |

? |

|

| Cooperative |

? |

|

| Poalei Zion |

? |

|

| Unaccounted |

10,536 |

4.15 |

| Total: |

253,813 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Cojocari |

Peasants Soviets |

| Erhan |

Peasants Soviets |

| Inculet |

Peasants Soviets |

| Katoros |

Peasants Soviets |

| Rudev |

Peasants Soviets |

| Stepanov |

Peasants Soviets |

| Aleksandrov |

SR |

| Imas |

SR |

| Mekhonoshin |

SR |

| Slonim |

SR |

| Sukhovikh |

SR |

| Sukhovikh |

SR |

| Lurie |

Menshevik-Bund |

| Urusov |

Kadet |

| Avilov |

Bolshevik |

|

Taurida

|

One peasant list had been denied registration.[50]

Taurida had a 54.74% voter turnout.[41] Radkey's account is missing Berdiansk uezd with some 3,400 electors and Vodiansk volost of Melitopol uezd.[58] All in all there were 753 precincts in the Taurida electoral district.[58] |

Taurida

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

300,100 |

52.22 |

| Turkic-Tatar |

68,581 |

11.93 |

| Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionaries |

61,541 |

10.71 |

| Kadets |

38,794 |

6.75 |

| Bolsheviks |

31,612 |

5.50 |

| Germans |

27,681 |

4.82 |

| Mensheviks |

15,176 |

2.64 |

| Jewish National Bloc |

13,986 |

2.43 |

| Landowner |

7,715 |

1.34 |

| Popular Socialists |

4,643 |

0.81 |

| Unity |

2,273 |

0.40 |

| Poalei Zion |

1,745 |

0.30 |

| Molokan |

885 |

0.15 |

| Total: |

574,732 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Bogdanov |

Kadet |

| Saltan |

Ukrainian SR |

| Alyasov |

SR |

| Bakuta |

SR |

| Bondar |

SR |

| Nikonov |

SR |

| Popov |

SR |

| Tolstov |

SR |

| Zak |

SR |

| Seidamet |

Provisional Crimean

Muslim Executive Committee |

|

Don Cossack Region

|

The Provisional Government had provided a degree of autonomy to the Don region, recognizing the authority of the Cossacks over the land. In June 1917 General Alexey Kaledin was elected as ataman. The Kadets had sought to form a joint Kadet-Cossack list in the district, and a number of Kadet national leaders had visited the area ahead of the election. The effort failed, over differences of opinion on land ownership of non-Cossacks.[24] |

Don Cossack Region

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| Cossack |

636,966 |

45.28 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

478,901 |

34.05 |

| Bolsheviks |

205,497 |

14.61 |

| Kadets |

43,345 |

3.08 |

| Mensheviks |

17,504 |

1.24 |

| Old Believer |

8,183 |

0.58 |

| Rightwing Socialist Bloc-Unity alliance |

5,718 |

0.41 |

| Landowner |

5,457 |

0.39 |

| Popular Socialists-Cooperative alliance |

5,049 |

0.36 |

| Total: |

1,406,620 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Babin |

SR |

| Kolesnikov |

SR |

| Kurilov |

SR |

| Mamonov |

SR |

| Nikolaev |

SR |

| Nikolsky |

SR |

| Shvetsov |

SR |

| Ageyev |

Cossack |

| Arakantsev |

Cossack |

| Bogaevsky |

Cossack |

| Kaledin |

Cossack |

| Kharlamov |

Cossack |

| Melnikov |

Cossack |

| Popov |

Cossack |

| Ulanov |

Cossack |

| Voronkov |

Cossack |

| Lozovsky |

Bolshevik |

| Syrtsov |

Bolshevik |

| Vasilchenko |

Bolshevik |

|

Stavropol

|

In Pyatigorsk the Bolsheviks won some 8,000 votes, half of the votes from the town.[89] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Bocharnikov |

SR |

| Dementiev |

SR |

| Emelyanov |

SR |

| Garnitsky |

SR |

| Gutorov |

SR |

| Onipko |

SR |

|

Kuban-Black Sea

|

Kuban was fully engulfed by civil war by the time of the vote.[3] 16 seats had been allotted to the Kuban-Black Sea electoral district, but the election was only held in Ekaterinodar and some surrounding villages were the Kuban Territorial Council was in control. [90]ref name=Wade2004e/> |

|

|

Ter-Dagestan

|

Voting was delayed in Ter-Dagestan and was held between November 26 and December 5. In some areas the votes were counted but not reported, in other areas votes were left uncounted. [91] In Radkey's account a complete result was only available for Vladikavkaz city. He includes sporadic results of the major parties in some towns and garrisons. Radkey's account contains no results from rural areas.[58]

Bolsheviks obtained 44% of the vote in Vladikavkaz. This situation could be compared to that by March 1917 the Bolshevik Party had been so weak in the city that it had been decided to form a joint Bolshevik-Menshevik Party Committee in the city.[89] According to Wade, the election was not carried through to completion in Ter-Dagestan.[3] |

|

|

Caspian

|

The Caspian electoral district, which included areas of the Kalmyk steppe of the Astrakhan Governorate, was thinly populated.[90] 1 seat was assigned to the constituency.[90] A special Pricaspian electoral district had been formed, including areas of the Kalmyk steppe of Astrakhan governorate.[5] The Pricaspian Oblast Election Commission was set up on September 16, 1917 by the Central Committee for the Kalmyk People's Administration.[5] The Chairman was B.E. Krishtafovich, CCKPA Chairman, accompanied by members I.O. Ochirov (assistant CCKPA chair), S.B. Bayanov, E.A. Sarangov, E.S. Bakayev and with F.I. Plyunov as its secretary.[5] On September 23, 1917 the Pricaspian Oblast Election Commission set up 52 electoral precincts: 10 in Maloderbetovsky ulus 10 precincts, 10 in Manychsky ulus, 7 in Yandyko-Mochaznyi ulus, 12 in Ikitsokhuro-Kharakhusovksy 12, 9 precincts in the uluses of Bagaotsokhuro-Khoshoutovsky and Erketenevsky and 4 precincts in the Kuma aimak of the Terek oblast (which initially had not been planned to be part of the Caspian Electoral District).[5] A list was submitted, signed by 137 electors, with the 33-year old lawyer Sandzhi Bayanovich Bayanov as its candidate.[5] Due to late arrival of electoral material, the vote was postponed to November 26-28, 1917.[5] The vote was reportedly held on these dates, in some places with very low turnout. Bayanov received a majority of votes.[5] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Bayanov |

? |

|

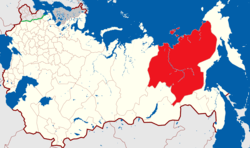

Transcaucasus

|

The vote was held November 26-28, within two weeks of the formation of the Transcaucasian Commissariat (Zavakom).[92] 15 lists were in the fray in Transcaucasus. [93]The three largest parties in Transcaucasus were the Mensheviks, the Musavat Party and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaksiun).[94] Whilst the Mensheviks were the most voted party, it should be noted that here Menshevism had become intertwined with Georgian nationalism. [95]Soon after the election, the Georgian Mensheviks would become openly nationalistic.[93]

Bolsheviks won the election Baku city (followed closely by Musavat and Dashnaksiun), Ittihad won the elections in the rural areas of Baku uezd, in the villages of the Absheron Peninsula. Musavat won most of the Azerbaijani vote in Baku guberniia, followed by Ittehad.[94] In Tiflis the Bolsheviks quadrupled their vote compared to the July 1917 city duma election.[96]

The numbers in the column to the right originate from Hovannisian (1967)[97] and Vestnik Evrazii (2004)[98] The source for Vestnik Evrazii for the results stems from the State Archive of the Russian Federation.[98]

These two references present a more complete account than that of Radkey. Radkey’s account lists a total of 1,887,453 votes, including 215,121 unspecified residue votes. [39] Radkey’s effort to map the votes in Transcaucasus was frustrated by the insistence of Soviet source to lump parties like Musavat and Dashnaksiun into a single bloc.[69]

Between Hovannisian and Vestnik Evrazii, the votes for the Mensheviks, Kadets, SRs and Bolsheviks are identical. Vestnik Evrazii presents the vote for the Popular Socialist list, which is not detailed in Hovannasian. Vestnik Evrazii groups the Dashnaks, the Muslim Socialist Bloc and Hummet together (825,672 votes) and 728,206 for Bourgeois parties (presumably including Musavat). In the case of Musavat, Hummet, Ittihad and Dashnaks, the figures from Hovannisian are used. Hovannisian does not present a total of votes, so the total from Vestnik Evrazii is utilized instead.

Comparing the account from Hovannisian with that of Swietochowski (2004)[92] the numbers for the Mensheviks, Musavat, the Muslim Socialist Bloc, SRs, Hummet and Ittihad are identical. The minor discrepancies between Hovannisian and Swietochowski are different vote for Bolshevik list (93,581 in Hovannisian and Vestnik Evrazii, 95,581 in Switeochowski), the Dashnaks got 40 votes more in Swietochowski’s account and Swietochowski lists a total of 2,455,274 (plus 2,172 compared to Vestnik Evrazii).[92] Maḣmudov (2004)[99] and Balaev (1998)[100] carries the same numbers as Swietochowski. |

Transcaucasus

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 1 - Mensheviks |

661,934 |

26.98 |

| List 10 - Musavat Party |

615,816 |

25.10 |

| List 4 - Armenian Revolutionary Federation |

558,440 |

22.76 |

| List 12 - Muslim Socialist Bloc |

159,770 |

6.51 |

| List 3 - Socialist-Revolutionaries |

117,522 |

4,79 |

| List 5 - Bolsheviks |

93,581 |

3.81 |

| List 11 - Hummet |

84,748 |

3.45 |

| List 14 - Ittihad |

66,504 |

2.71 |

| List 2 - Kadets |

25,637 |

1.05 |

| List 9 - Popular Socialists |

514 |

0.02 |

Others:[101]

List 6 - Georgian Socialist-Federalists

List 7 - Armenian Populist Party

List 8 - Georgian National Democrats

List 13 - Transcaucasian Muslims

List 15 - Zionists |

68,636 |

2.80 |

| Total: |

2,453,102 |

|

|

|

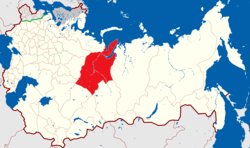

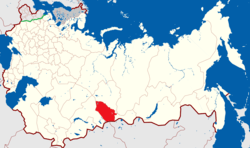

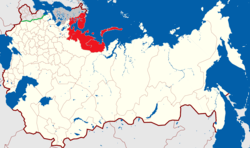

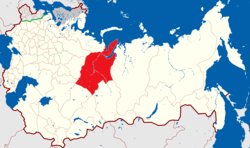

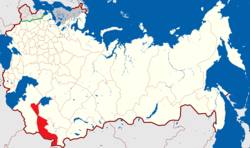

Tobolsk

|

Tobolsk hosted one of only 2 undivided Social Democratic lists in the fray across the country. [102] Soviet sources indicated that the Social Democratic list was Menshevik-dominated. [48]

Soviet sources reported voter turnout at a mere 33.5%.[41] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Sukhanov, A. S. |

Peasants Union-

Popular Socialists alliance |

| Barantsev |

SR |

| Evdokimov |

SR |

| Gul'tyaev |

SR |

| Ivanitsky-Vasilenko |

SR |

| Kotelnikov |

SR |

| Krasnousov |

SR |

| Mikhailov |

SR |

| Mukhin |

SR |

| Sukhanov, P. S. |

SR |

|

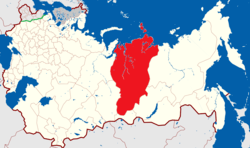

Steppe

|

Radkey's account only includes votes from Omsk and surroundings.[58] According to Wade (2004), it is unclear whether the election was carried through to completion in the electoral district.[3] |

|

|

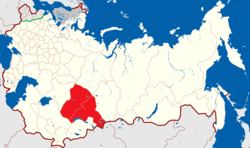

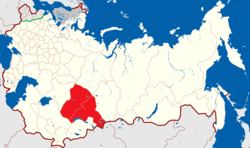

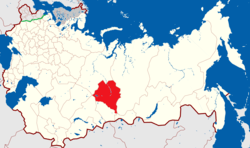

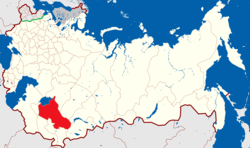

Tomsk

|

3 out of 9 lists submitted were rejected by the electoral authorities, including a moderate Turko-Tatar list.[50][39]

12,046 votes were cast at the Tomsk garrison. The Bolshevik list won 69% of the votes there, with 8,316 votes. The SR list got 2,683 votes (22.27%), the Kadet list 385 votes (3.20%), Popular Socialist 278 votes (2.31%), 73 votes (0.61%) for the Menshevik list and 10 votes (0.08%) for the Cooperative list.[103] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Smirnov |

Bolshevik |

| Grigoriev |

SR |

| Lindberg |

SR |

| Markov |

SR |

| Markov |

SR |

| Mikhailov |

SR |

| Omelkov |

SR |

| Semenov |

SR |

| Shisharin |

SR |

| Sukhomlin |

SR |

|

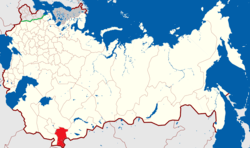

Altai

|

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Devisorov |

SR |

| Krivorotov |

SR |

| Levin |

SR |

| Lomshakov |

SR |

| Lyubimov |

SR |

| Ramazanov |

SR |

| Rogovsky |

SR |

| Rudnev |

SR |

| Sotnin |

SR |

| Shaposhnikov |

SR |

| Shnyrev |

SR |

| Kosorotov |

SR |

| Shatilov |

SR |

|

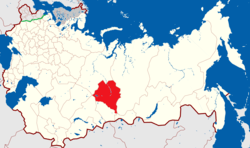

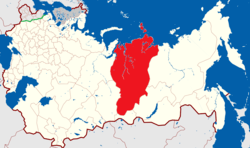

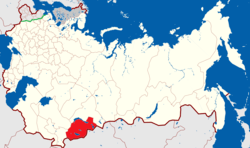

Yenisei

|

1 submitted peasant list was rejected.[50] According to Radkey the results from Krasnoyarsk city and 5 out of 6 uezds appeared complete, with thinly populated Turukhansk uezd missing.[58] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Okulov |

Bolshevik |

| Rogov |

Bolshevik |

| Eideman |

SR |

| Fomin |

SR |

| Gurov |

SR |

| Kolosov |

SR |

|

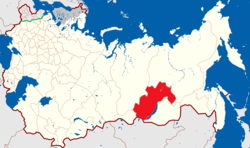

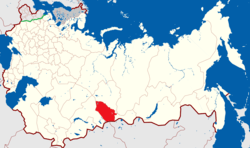

Irkutsk

|

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Korshunov |

SR |

| Krol |

SR |

| Timofeev |

SR |

| Vampiloon |

Buryat |

| Gavrilov |

Bolshevik |

|

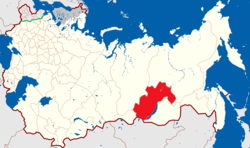

Transbaikal

|

6 out of the 15 submitted lists in Transbaikal were rejected.[50] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Bogdanov |

Buryat National Committee |

| Dobromyslov |

SR |

| Flegontov |

SR |

| Kruglikov |

SR |

| Pumpyanskiy |

SR |

| Simakov |

SR |

| Taskin |

Transbaikal Cossacks |

|

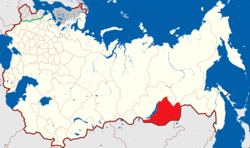

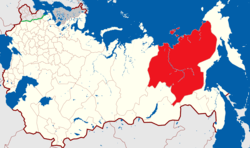

Amur-Maritime

|

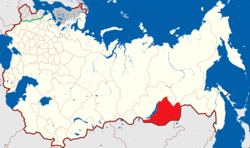

The Amur-Maritime electoral district consisted of the Amur region and the Maritime province.[87] The election was held on time in the constituency. From the Maritime Province the results were seemingly complete. In areas north of the Amur river some problems in voting occurred, with 312 polling stations reporting and 77 didn't (another reference stated that no election had been held in some 50 polling stations). The constituency had no significant ethnic minority except Ukrainians[104]

The SRs had suffered a four-way split in the constituency, with the branches in Amur and Maritime contesting separately. Ahead of the election the Maritime Province Peasants Soviets threw out the SR party representatives and fielded a separate list (in Amur, however, the peasants soviets stayed loyal to the SR party).[87] There was also a left SR list, distinctively urban.[87]

In Khabarovsk, 5,445 out of 12,727 eligble voters cast their votes; Kadets 1,639 votes (30.10%), Maritime Province SR 968 votes (17.78%), Maritime Peasants Soviet 712 votes (13.08%), Mensheviks 662 votes (12.16%), Bolsheviks 652 votes (11.97%), Cossacks 623 votes (11.44%), Ukrainian Bloc 85 votes (1.56%), Amur SR 24 votes (0.44%) and Left SR 18 votes (0.33%).[105]

In Blagoveshchensk the Kadets finished in first place (with some 2,800 votes), followed by the Mensheviks (2,300 votes), Bolsheviks (1,983 votes) and Amur SRs (1,267) votes.[105] In Nikolayevsk-on-Amur 1,529 votes were cast; Kadets 411 votes (26.88%), Maritime Province SRs 400 votes (26.16%), Mensheviks 311 votes (20.34%), Bolsheviks 287 votes (18.77%) and others 120 votes (7.85%).[105] |

Amur-Maritime

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 2 - Maritime Peasants Soviets |

56,718 |

27.08 |

| List 7 - Amur Province Socialist-Revolutionaries |

41,152 |

19.65 |

| List 5 - Bolsheviks |

40,850 |

19.50 |

| List 3 - Amur and Ussuri Cossacks |

22,612 |

10.80 |

| List 9 - Kadets |

17,233 |

8.23 |

| List 4 - Mensheviks |

15,458 |

7.38 |

| List 1 - Maritime Province Socialist-Revolutionaries |

6,513 |

3.11 |

| List 8 - Left Socialist-Revolutionaries |

5,805 |

2.77 |

| List 6 - Ukrainian Bloc |

3,125 |

1.49 |

| Total: |

209,466 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Mandrikov |

Maritime Peasants Soviet |

| Petrov |

Maritime Peasants Soviet |

| Sorokin |

Maritime Peasants Soviet |

| Vykhristov |

Maritime Peasants Soviet |

| Kozhevnikov |

Amur and Ussuri Cossacks |

| Neibut |

Bolshevik |

| Alekseevsky |

Amur SR |

|

| Chinese Eastern Railroad |

The Chinese Eastern Railroad electoral district was located outside the borders of Russia.[3] In March 1917, in response to the abdication of the Tsar, Lieutenant General Dmitri Horvath (the Chinese Eastern Railroad Zone administrator since 1902) proclaimed an 'All Russian Provisional Government' based in Harbin.[106][107][108] However, Horvath's regime was soon challenged by emergence of soviet power in the Chinese Eastern Railroad Zone (to the dismay of Western powers).[106] Nevertheless, Harbin was far detached from events in Petrograd and a more liberal atmosphere prevailed in Russian politics there; foreign diplomats took note that the monarchist Horvath and the Bolshevik leader Martemyan Ryutin could meet for lunch at the Railway Club in Harbin.[109]

Four candidates were nominated for the Chinese Eastern Railroad seat; Horvath ran as the Kadet candidate, representing the pre-revolutionary status quo. Nikolai Strelkov of the Railwaymens' Union contested as the Menshevik candidate, the Jewish businessman and Chair of the Chinese Eastern Railroad Executive Committee Faytel Volfovich was the SR candidate and the ensign and Harbin Soviet chairman Ryutin the Bolshevik candidate.[110][111][112][109]

The vote was held for the Chinese Eastern Railroad seat on November 29, 1917.[111] The voter turnout stood at around 60%.[110]

According to a contemporary account published in the organ of the Nikolsk-Ussuriysky Soviet (whose totals differ somewhat from the figures of Radkey), the vote in Harbin was won by Strelkov (4,874 votes, 31.74%), followed by Horvath (4,450 votes, 28.98%), Ryutin (4,412 votes, 28.73%) and Volfovich (1,620 votes, 10.55%).[105] In the 26 precincts of the western line, Ryutin was the most vote candidate (5,991 votes, 38.25%), followed by Strelkov (5,845 votes, 37.32%), Volfovich (2,519 votes, 16.08%) and Horvath (1,307 votes, 8.35%).[105] In the four precincts of the eastern line, Ryutin emerged as the winner with 1,461 votes (39.84%), followed by Strelkov (1,187 votes, 32.37%), Volfovich (831 votes, 22.66%) and Horvath (188 votes, 5.13%).[105] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Strelkov |

Menshevik |

|

Yakutsk

|

An election was held and deputies elected, but Radkey was unable to trace the any voting figures.[90] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Xenophonov |

Federal Labour Union |

| Pankratov |

SR |

|

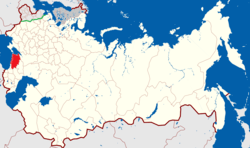

Kamchatka

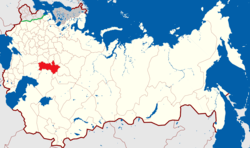

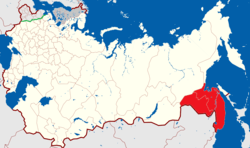

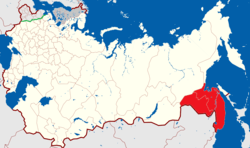

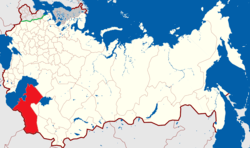

.png) |

The vote was held in the Kamchatka electoral on October 29, 1917, well ahead of the rest of the country, in order to allow its sole deputy to be able to catch the last steamship to Petrograd to attend the opening of the Constituent Assembly.[3] Radkey claims to only have been able to trace results from the town of Zavoyko, but the Zavoyko poll was disqualified as the vote had been held one day in advance.[58] 275 people had voted in Zavoyko, 258 of them for SR, 9 for Social Democrats and 8 for others. [39] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Lavrov |

SR |

|

Horde

|

The Horde (or 'Orda') electoral district covered the areas of the Bukey Horde in the Transvolga.[3] Khanskaya Stavka was the administrative center of the electoral district.[3] According to Radkey, 2 lists had registered in the Horde electoral district. As per Radkey's account, no information on whether election was held.[39] As per Wade (2004), members of the local revolutionary committee began arresting the District Election Commission officials as the vote tallying was ongoing.[3] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Kulmanov |

Alash |

| Tanachev |

Alash |

|

Uralsk

|

|

Uralsk

| Party |

Vote |

% |

|---|

| List 1 - Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

278,014 |

75.01 |

| Cossack |

61,476 |

16.59 |

| Peasants |

26,059 |

7.03 |

| Socialist-Revolutionaries |

5,076 |

1.37 |

| Total: |

370,625 |

|

|

Deputies Elected

| Alibekov |

Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

| Dosmukhamedov, J. D. |

Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

| Dosmukhamedov, K. D. |

Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

| Ipmagambetov |

Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

| Karatlev |

Ural Regional Kirghiz Committee |

| Borodin |

Cossack |

| Volosov |

SR |

|

Turgai

|

According to Radkey the vote was held in one uezd, but that the result was not known.[39] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Baitursynov |

Alash |

| Berimzhanov |

Alash |

| Doshchanov |

Alash |

| Temirov |

Alash |

| Pakhomov |

SR |

|

Transcaspian

|

The Transcaspian electoral district was assigned 2 seats in the Constituent Assembly.[90] According to Radkey, an election was held but results not known.[90] Per Wade (2004), it is certain that no election took place in the Transcaspian electoral district.[3] |

|

|

Samarkand

|

Samarkand was assigned 5 seats.[90] According to Radkey, an election was held but results were not known to him.[90] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Abdukhalilov |

Muslim organizations of

the Samarkand region |

| Behbudiy |

Muslim organizations of

the Samarkand region |

| Farhatov |

Muslim organizations of

the Samarkand region |

| Maksudi |

Muslim organizations of

the Samarkand region |

|

Amu Darya

|

According to Radkey, not known whether voting took place, no results. 1 seat had been allotted to Amu Darya.[90] Per Wade (2004), it is certain that no election took place in Amu Darya.[3] |

|

|

Syr Darya

|

Voting was postponed until mid-Dec 1917, then to January 19, 1918.[91] In the end no vote ever took place.[91][3] 9 seats had been allotted to Syr Darya.[90] |

|

|

Fergana

|

Election was held and deputies elected, but Radkey unable to trace the any voting figures.[90] Seemingly, per Soviet sources cited by Radkey, there were 5 deputies elected from Fergana, out of whom 1 SR.[59] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Khodzhaev |

Muinil Islam Society |

| Tyuryayev |

Muinil Islam Society |

| Akaev |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Chaykin |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Shokay |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Mirza-Akhmedov |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Shagiakhmetov |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Shashahmedov |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Urazaev |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Yuldash-Kariev |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

| Yurgul-Agayev |

All-Fergana List of Muslim Organizations |

|

Semirechie

|

The electoral battle in Semirechie stood between a general soviet list (SRs and Mensheviks) and the Kirgiz-Cossack alliance. The Bolshevik list had been banned. [39] |

|

Deputies Elected

| Shebalin |

Socialist Bloc |

| Tynyshpaev |

Socialist Bloc |

| Amanzholov |

Alash-Cossack alliance |

| Jainakov |

Alash-Cossack alliance |

| Saurambaev |

Alash-Cossack alliance |

| Shendrikov |

Alash-Cossack alliance |

|

| Baltic Fleet |

The Baltic Fleet was a revolutionary bastion.[77] Electoral participation stood at around 70%. 76% of sailors voted, but the sailors were outnumbered by workers and soldiers at the naval bases.[41] Baltic Fleet used a separate electoral system, where the voter could vote for two individual candidates rather than fixed party lists.[113][114]

The Bolsheviks in Tsentrobalt submitted their petition, with some two hundred signatures, to the electoral commission on October 12, 1917.[114] Their list had Lenin as its first candidate and with Pavel Dybenko as its second name.[114] Whilst the conducting the election campaign, the Bolsheviks in the Baltic Fleet prepared their role in the pending uprising against the Provisional Government.[114]