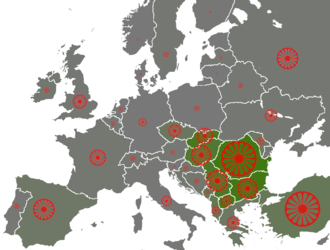

Romani diaspora

* The size of the wheel symbols reflects absolute population size

* The gradient reflects the percent in the country's population: 0% 10%.

The Roma people have a number of distinct populations, the largest being the Roma and the Iberian Calé or Caló, who reached Anatolia and the Balkans about the early 12th century, from a migration out of northwestern India beginning about 600 years earlier.[2][3] They settled in present-day Turkey, Greece, Serbia, Romania, Croatia, Moldova, Bulgaria, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Hungary and Slovakia, by order of volume, and Spain. From the Balkans, they migrated throughout Europe and, in the nineteenth and later centuries, to the Americas. The Romani population in the United States is estimated at more than one million.[4]

There is no official or reliable count of the Romani populations worldwide.[5] Many Romani refuse to register their ethnic identity in official censuses for fear of discrimination.[6] Others are descendants of intermarriage with local populations and no longer identify only as Romani, or not at all.

As of the early 2000s, an estimated 4 to 9 million Romani people lived in Europe and Asia Minor.[7] although some Romani organizations estimate numbers as high as 14 million.[8] Significant Romani populations are found in the Balkan peninsula, in some Central European states, in Spain, France, Russia, and Ukraine. The total number of Romani living outside Europe are primarily in the Middle East and North Africa and in the Americas, and are estimated in total at more than two million. Some countries do not collect data by ethnicity.

The Romani people identify as distinct ethnicities based in part on territorial, cultural and dialectal differences, and self-designation. The main branches are:[9][10][11][12]

- Roma, concentrated in Central and Eastern Europe and Italy, they emigrated (mostly from the 19th century onwards) to the rest of Europe, as well as the Americas;

- Iberian Kale, mostly in Spain (see Romani people in Spain), but also in Portugal (see Romani people in Portugal), Southern France and Latin America;

- Finnish Kale, in Finland, emigrated also in Sweden;

- Welsh Kale, in Wales and the British Isles;

- Romanichal, in the United Kingdom, some emigrated also to the United States, Canada and Australia;

- Sinti, in German-speaking areas of Europe and some neighboring countries;

- Manush, in French-speaking areas of Europe (in French: Manouche); and

- Romanisæl, in Norway and Sweden.

The Romani have additional internal distinctions, with groups identified as Bashaldé; Churari; Luri; Ungaritza; Lovari (Lovara) from Hungary; Machvaya (Machavaya, Machwaya, or Macwaia) from Serbia; Romungro from Hungary and neighbouring Carpathian countries; Erlides (also Yerlii or Arli); Xoraxai (Horahane) from Greece/Turkey; Boyash (Lingurari, Ludar, Ludari, Rudari, or Zlătari) from Romanian/Moldovan miners; Ursari from Romanian/Moldovan bear-trainers; Argintari from silversmiths; Aurari from goldsmiths; Florari from florists; and Lăutari from singers.

Population by country

This is a table of Romani people by country. The list does include the Dom people, who are often subsumed under "gypsies".

The official number of Romani people is disputed in many countries; some do not collect data by ethnicity; in others, Romani individuals may refuse to register their ethnic identity for fear of discrimination,[13] or have assimilated and do not identify exclusively as Romani. In some cases, governments consult Romani organizations for data.

| Country | Region | Population | Subgroups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Southern Europe, Balkans | 8,301 (0.3%) (official 2011 census)[14] | Gabel (Vlax Roma), Jevgs |

| Algeria | Africa | 40,000 | Nawar people, Dom people, Kale |

| Angola | Africa | 16,000 | Kale (from Portugal) |

| Argentina | Overseas | 300,000 | Kalderash, Boyash, Kale |

| Australia | Overseas | 5,000+[15] | Romanichal, Boyash |

| Austria | Central Europe | 20,000–50,000[16][17] | Burgenland-Roma, Sinti, Lovari, Arlije from Macedonia, Kalderash from Serbia, Gurbeti from Serbia and Macedonia |

| Azerbaijan | Asia | 2,000 [18] | Garachi |

| Belarus | Eastern Europe | 10,000 (census data) or 50,000–60,000 (estimated data)[19][20] | |

| Belgium | Western Europe | 10,000–15,000[16] | Romungro |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Southern Europe, Balkans | 6,000–9,000 | |

| Brazil | Overseas | 678,000–1,000,000 | Kale, Kalderash, Machvaya, Xoraxane, Boyash |

| Bulgaria | Southern/Eastern Europe, Balkans | 370,908 (official census) to 600,000[21] | Yerli, Gurbeti, Kalderash, Boyash, Ursari |

| Canada | Overseas | 80,000[22] | Kalderash, Romanichal |

| Chile | Overseas | 15,000–20,000 | Xoraxane |

| China | Asia | 9,000 | Vlax (Kalderash, Lovara, Potkovari) |

| Colombia | Overseas | 4,850[23][24] | Kalderash |

| Croatia | Central / Southern Europe, Balkans | 2,500 (census results)[25] Estimated:3,000[26] | Lovari, Boyash |

| Czech Republic | Central Europe | 5,199 (official census)[27] 150,000–300,000 (official 2006 government estimate)[28] | Romungro; Bohemian Roma |

| Denmark | Northern Europe | 1,500–2,000[16] | |

| Ecuador | Overseas | 2,000 | Kalderash |

| Estonia | Northern Europe | 456[29] | |

| Finland | Northern Europe | 10,000+ [30][31] | Kàlo |

| Egypt | Africa | 2,300,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| France | Western Europe | 500,000 (official estimation) 1,200,000–1,300,000 (unofficial estimation)[32][33] | Manush, Kalderash, Lovari, Sinti |

| Germany | Central / Western Europe | 500,000[34] | mostly Sinti, but also Balkan Roma, Vlax Roma |

| Georgia | Eastern Europe/Western Asia | 500+[35] | Roma, Domari, Lom/Bosha |

| Greece | Southern Europe, Balkans | 200,000 or 300,000 [36] | Erlides, Xoraxane, |

| Hungary | Central/Eastern Europe | 205,984 (census);[37] 394,000–1,000,000 (estimated)[38][39][40] |

Romungro, Boyash, Lovari |

| Iran | Asia | 760,000[41] | Domari, Koeli, Ghorbati, Nawari |

| Iraq | Asia | 23,000 | Nawar people, Qawliya, Kalderash, Xoraxane |

| Ireland | Northern Europe | 3,000[42] | |

| Italy | Southern Europe | 90,000–180,000[16] + 152,000 illegal Roma in 700 camps[43] | Sinti, Ursari, Kalderash, Xoraxane |

| Kazakhstan | Asia | 7,000 | Sinti[44] |

| Latvia | Northern Europe | 8,482 (2012 est.)[45] or 13,000–15,000[46] | Lofitka Roma (in same Baltic Romani dialect family as Polska Roma and Ruska Roma) |

| Lebanon | Asia | 12,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| Libya | Africa | 40,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| Lithuania | Northern Europe | 3,000–4,000[16] | |

| Luxembourg | Western Europe | 100–150[16] | |

| Macedonia | Southern Europe, Balkans | 53,879 Roma and 3,843 Balkan Egyptians to 260,000[47] | Yerli, Gurbeti, Cergari, Egyptians |

| Mexico | Overseas | 16,000 | Kale, Boyash, Machwaya, Lovari, Gitanos, Kalderash[48] |

| Moldova | Eastern Europe | 12,900 (census) to 20,000–25,000[16] or 150,000[49][50] | Rusurja, Ursari, Kalderash |

| Montenegro | Southern Europe, Balkans | 2,601 to 20,000,[51] additionally 8,000 registered Roma refugees from Kosovo, the entire number of IDP Kosovarian Roma in Montenegro is twice as large.[51] | |

| Morocco | Africa | 50,000 | Nawar people, Dom people, Kale, Gitanos, Kalderash, Boyash |

| Netherlands | Western Europe | 35,000–40,000[16] | |

| Norway | Northern Europe | 6,500 or more[52] | Norwegian and Swedish Travellers (Romanoar, Tavringer), Vlax |

| Peru | Overseas | 8,400[53] | Kalderash, Calo |

| Poland | Central/Eastern Europe | 15,000–60,000[54][55] | Polska Roma |

| Portugal | Southern / Western Europe | 40,000[16][56][57] | |

| Romania | Southern/Central/Eastern Europe | 621,573 (2011 census) 850,000 (estimated)[58][59][60] | Kalderash, Ursari, Lovari, Vlax, Romungro |

| Russia | Eastern Europe | 182,766 (census 2002) or 450,000–1,000,000 (estimated)[61][50] | Ruska Roma (descended from Polska Roma, from Poland), Kalderash (from Moldova), Servy (from Ukraine and Balkans), Ursari (from Bulgaria) Lovare, Wallachian Roma (from Wallachia). |

| Serbia | Southern Europe, Balkans | 147,604 (census 2011) or 400,000–800,000 (estimated) [51][62] | See Romani people in Serbia. Main sub-groups include "Turkish Gypsies", "White Gypsies", "Wallachian Gypsies" and "Hungarian Gypsies".[63] |

| Slovakia | Central/Eastern Europe | 92,500 or 550,000[64][65][66][67][68] | Romungro |

| Slovenia | Central / Southern Europe, Balkans | 3,246–10,000[16][69] | |

| South Africa | Overseas | 7,900 | Romanichal |

| Spain | Southern / Western Europe | 1,000,000 (official estimation)[70] 600,000–800,000 [71] or 1,500,000[72][73] | Gitanos, Kalderash, Boyash |

| Sudan | Africa | 50,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| Sweden | Northern Europe | 30,000–65,000[74] | Swedish Travellers (Tavringer), Vlax (Kalderash, Lovara), Kàlo (Finnish Roma) |

| Switzerland | Central / Western Europe | 30,000–35,000[16] | |

| Syria | Asia | 46,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| Thailand | Asia | 10,000–50,000 | Moken Sea Gypsies people |

| Tunisia | Africa | 20,000 | Nawar people, Dom people |

| Turkey | Southern/Eastern Europe, Balkans, Asia | 35,000[75] to 5,000,000[76] | Bosha, Yerli |

| Ukraine | Eastern Europe | 47,587 (census 2001) or 400,000 (estimated)[77] | Kelderare (Hungarian name for Kotlyary; Zakarpattia), Kotlyary (other Ukrainian regions), Ruska Roma (northern Ukraine), Servy (Serby, southern and central Ukraine, from Serbia), Lovare (central Ukraine), Kelmysh, Crymy (in Crimea), Servica Roma (in Zakarpattia from Slovakia), Ungriko Roma (in Zakarpattia from Hungary)[78][79] |

| United Kingdom | Northern / Western Europe | 44,000–94,000+[80][15] Unspecified number of Romani immigrants from Eastern Europe (among them in 2004 there were 4,100 Vlax Roma)[23] and additionally 200,000 recent migrants[81] | Romanichal, Welsh Kale |

| United States | Overseas | 1,000,000 (Romani organizations' estimations) | |

| Uruguay | Overseas | 2,000–5,000 | |

Central and Eastern Europe

A significant proportion of the world's Romanies live in Central and Eastern Europe, often in squatter communities with very high unemployment, while only some are fully integrated in the society. However, in some cases—notably the Kalderash clan in Romania, who work as traditional coppersmiths—they have prospered. Some Romani families choose to immigrate to Western Europe now that many of the former Communist countries like the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria have entered the European Union and free travel is permitted. During the 1970s and 1980s many Romanies from former Yugoslavia migrated to Western European countries, especially to Austria, Germany and Sweden.

Bulgaria

Romani people constitute the third largest ethnic group (after Bulgarians and Turks) in Bulgaria, they are referred to as "цигани" (cigani) or "роми" (romi). According to the 2001 census, there were 370,908 Roma in Bulgaria, equivalent to 4.7% of the country's total population.[82]

Greece

The Romani people of Greece are called Arlije or Erlides. The number of Roma in Greece is currently estimated to be between 200,000 and 350,000 people.[36]

Hungary

In the 2011 census, 315,583 people called themselves Roma.[83] Various estimations put the number of Roma people to be between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people, or 8-10% of Hungary's population.[84][85]

.jpg)

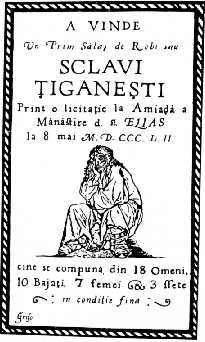

Romania

There is a sizable minority of Romani people in Romania, known as Ţigani in Romanian and, recently, as Rromi, of 621,573 people or 3.3% of the total population (2011 census). There exist a variety of governmental and non-governmental programs for integration and social advancement, including the National Agency for the Roma and Romania's participation in the Decade of Roma Inclusion. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Spain participate in these programs. As an officially recognized ethnic minority, the Romani people also have guaranteed representation in Parliament.

Russia

In Russian the Romani people are referred to as tzigane. The largest ethnic group of Romani people in Russia are the Ruska Roma. They are also the largest group in Belarus. They are adherents of the Russian Orthodox faith.

They came to Russia in the 18th century from Poland, and their language includes Polish, German, and Russian words.

The Ruska Roma were nomadic horse traders and singers. They traveled during the summer and stayed in cottages of Russian peasants during the winter. They paid for their lodging with money, or with the work of their horses.

In 1812, when Napoleon I invaded Russia, the Romani diasporas of Moscow and Saint Petersburg gave large sums of money and good horses for the Russian army. Many young Romani men took part in the war as uhlans.

At the end of the 19th century, Rusko Rom Nikolai Shishkin created a Romani theatre troupe. One of its plays was in the Romani language.

During World War II some Ruska Roma entered the army, by call-up and as volunteers. They took part in the war as soldiers, officers, infantrymen, tankmen, artillerymen, aviators, drivers, paramedical workers, and doctors. Some teenagers, old men and adult men were also partisans. Romani actors, singers, musicians, dancers (mostly women) performed for soldiers in the front line and in hospitals. A huge number of Roma, including many of the Ruska Roma, died or were murdered in territories occupied by the enemy, in battles, and in the blockade of Leningrad.

After World War II, music of the Ruska Roma became very popular. Romen Theatre, Romani singers and ensembles prospered. All Romanies living in the USSR began to perceive Ruska Roma culture as the basic Romani culture.

Western Europe

Spain

Romanies in Spain are generally known as Gitanos and tend to speak Caló which is basically Andalusian Spanish with a large number of Romani loanwords.[86] Estimates of the Spanish Gitano population range between 600,000 and 1,500,000 with the Spanish government estimating between 650,000 and 700,000.[87] Semi-nomadic Quinqui consider themselves apart from the Gitanos.

Portugal

The Romanies in Portugal are known as Ciganos, and their presence goes back to the second half of the 15th century. Early on, due to their socio-cultural difference and nomadic style of live, the Ciganos were the object of fierce discrimination and persecution.[88]

The number of Ciganos in Portugal is difficult to estimate, since there are no official statistics about race or ethnic categories. According to data from Council of Europe's European Commission against Racism and Intolerance[89] there are about 40,000 to 50,000 spread all over the country.[90] According to the Portuguese branch of Amnesty International, there are about 30,000 to 50,000.[91]

France

Romanies are generally known in spoken French as Manouches or Tsiganes. Romanichels or Gitans are considered pejorative and Bohémiens is outdated. The French National Gendarmerie tends to refer to "MENS" ("Minorités Ethniques Non-Sédentarisées"), a neutral administrative term meaning Traveling Ethnic Minorities. Traditionally referred to as gens du voyage ("traveling people"), a term still occasionally used by the media, they are today generally referred to as Rroms. By law, French municipalities over 5,000 inhabitants have the obligation to allocate a piece of land to Romani travellers when they arrive.[92]

Approximately 500,000 Roma live in France as part of established communities. Additionally, the French Roma rights group FNASAT reports that there are at least 12,000 Roma, primarily from Romania and Bulgaria, living in illegal urban camps throughout the country. French authorities often close down these encampments. In 2009, the government returned more than 10,000 Roma illegal immigrants to Romania and Bulgaria.[93] In the Summer of 2012, with mounting criticism of their treatment of the Roma, French key ministers met for emergency talks on the handling of an estimated 15,000 Roma living in camps across France. They proposed to lift restrictions on migrants (including Roma) from Bulgaria and Romania who were working in France.[94]

Italy

Romani in Italy are generally known as zingaro (with the plural zingari), a word also used to describe a scruffy or slovenly person or a tinker. The word is likely of Greek origin meaning "untouchables", compare the modern Greek designations Τσιγγάνοι (Tsingánoi), Αθίγγανοι (Athínganoi). People often use the term "Rom", although the people prefer Romani (in Italian Romanì), which is little used. They are sometimes called "nomads," although many live in settled communities.

Northern Europe

Finland

The Kale (or Kaale) Romani of Finland are known in Finnish as mustalaiset ('blacks', cf. Romani: kalò, 'black') or romanit. Approximately 10,000 Romani live in Finland, mostly in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. In Finland, many Romani people wear their traditional dress in daily life.[95]

Norway and Sweden

Romani in Sweden were formerly known as zigenare for Roma and tattare for Scandinavian travellers. More recently the term romer has been adopted as a collective designation referring to both groups, with resande (travellers) also referring to the latter only. Approximately 120,000 Romani live in Sweden,[96] many of them descended from Finnish Kale who immigrated in the 1960s. The latter, particularly the women, often wear traditional dress.[97]

The Romani in Sweden have periodically suffered discrimination at the hands of the state. For example, the state has taken children into foster care, or sterilised Romani women without their consent. Prejudice against Romanies is widespread, with most stereotypes portraying the Romani as welfare cheats, shoplifters, and con artists. For example, in 1992, Bert Karlsson, a leader of Ny Demokrati, said, "Gypsies are responsible for 90% of crime against senior citizens" in Sweden.[98] He had earlier tried to ban Romani from his Skara Sommarland theme park, as he thought they were thieves. Some shopkeepers, employers and landlords continue to discriminate against Romani.[99]

The situation is improving. Several Romani organisations promote education about Romani rights and culture in Sweden. Since 2000, Romani chib is an officially recognised minority language in Sweden. The Swedish government has established a special standing Delegation for Romani Issues. A Romani folk high school has been founded in Gothenburg.[100]

United Kingdom

Romani in England are generally known as Romanichals or Romani Gypsies, while their Welsh equivalent are known as Kale. They have been recorded in the UK since at least the early 16th century. Records of Romani people in Scotland date to the early 16th century. Some emigrated to the British colonies and to the United States during the centuries. They may number up to 120,000. There is also a sizable population of East European Roma, who immigrated into the UK in the late 1990s/early 2000s, and also after EU expansion in 2004.

The first recorded reference to "the Egyptians" appeared to be in 1492, during the reign of James IV, when an entry in the Book of the Lord High Treasurer records a payment "to Peter Ker of four shillings, to go to the king at Hunthall, to get letters subscribed to the 'King of Rowmais'". Two days after, a payment of twenty pounds was made at the king's command to the messenger of the 'King of Rowmais'.[101]

According to the Scottish Traveller Education Programme, an estimated 20,000 Scottish Gypsies/Travellers live in Scotland.[102] It is not known how many of this number are ethnic Romani, rather than other Travellers. The society and government recognize that there are several ethnic groups, each with different histories and cultures.

The term "gypsy" in the United Kingdom has come to mean anyone who travels with no fixed abode (regardless of ethnic group). This use has often been synonymous with "pikey" , now considered a derogatory term. In some parts of the UK, the Romani are commonly called "tinkers" because of their traditional trade as tinsmiths.

West Asia

One route taken by the medieval proto-Romani cut across Persia and Asia Minor to Europe. Numerous Romani continue to live in Asia Minor. Other Romani populations in the Middle East are the result of modern migrations from Europe. Also found in the Middle East are various groups of the Dom people, often identified as "gypsies." They are derived from a migration out of northwestern India beginning about 600 years earlier.[2][3]

Cyprus

History

Historians estimate that the first immigrants came between 1322 and 1400, when Cyprus was under the rule of the Lusignan (Crusader) kings. These Roma were part of a general movement from Asia Minor to Europe. Those who landed on Cyprus probably came across from the Crusader colonies on the eastern Mediterranean coast (present-day Lebanon and Israel).[103]

There is no evidence suggesting one cause for the Roma to leave mainland Asia, but historical events caused widespread upheaval and may have prompted a move to the island. In 1347 the Black Death had reached Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire; in 1390 the Turks defeated the Greek kingdom in Asia; and ten years later, the Battle of Aleppo marked the advance of the Mongols under Tamerlane.

The first surviving written record of Roma in Cyprus is from 1468. In the Chronicle of Cyprus compiled by Florio Bustron, the Cingani are said to have paid tax to the royal treasury, at that time under King James II. Later, in 1549, the French traveler Andre Theret found "les Egyptiens ou Bohemiens" in Cyprus and other Mediterranean islands. He noted their simple way of life, supported by the production of nails by the men and belts by the women, which they sold to the local population.

During the Middle Ages, Cyprus was on a regular shipping route from Bari, Italy to the Holy Land. A second immigration likely took place some time after the Turks dominated the island in 1571. Some Kalderash came in the 19th century.

Currently, Roma in Cyprus refer to themselves as Kurbet, and their language as Kurbetcha, although most no longer speak it. Christian or Greek-speaking Roma are known as Mantides.[104]

According to the Council of Europe there are 1000-1500 (0,16%) Romanis living in Cyprus .[105]

Names of Roma in Cyprus

- Tsignos: the official term used in Greek documents and written material. It comes from the term Cingani (used in the 1468 text), which in turn comes from the archaic word Adsincan, used in mediaeval Byzantium.

- Yleftos: the Cypriot dialect form of mainland Greek Giftos. This is common in speech and comes from earlier Aigiptos, a reference to the earlier belief that the Romanies came from Egypt.[103]

- Kurbet: the local term used by turcophone Cypriots, a Roma group of Doms which is also present in Syria.[106]

(For additional names of Roma in Greek-speaking Cyprus, see Roma in Greece)

Israel

Some Eastern European Romani are known to have arrived in Israel in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Romani community in Israel has grown since the 1990s, as some Roma immigrated from states of the former Soviet Union.

A community anciently related to the Romani are the Dom people. Some live in Israel, the Palestinian territories and in neighboring countries.

Lebanon

It is estimated that there are 5,000 Romanis or Domaris in Lebanon [107]. The language of Romanis is called Domari in Lebanon and neighboring countries[108]. There is evidence that child labor was prevalent in Romani communities in Lebanon[109].

Turkey

Romani people in Turkey are generally known as Çingene, Çingen, or Çingan, as well as Çingit (West Black Sea region), Cono (South Turkey), Kıptî (meaning Coptic), Şopar (Kırklareli), Roman (İzmir) [110] and Gipleri (derived from the term "Egyptian"). Since the late twentieth century, some have started to recognize and cherish their Romani background as well.[111] Music, blacksmithing and other handicrafts are their main occupations.

Overseas

Most Romani populations overseas were founded in the 19th century by emigration from Europe.

North America

United States

At the beginning of the 19th century, the first major Romani group, the Romanichal from Great Britain, arrived in North America, although some had also immigrated during the colonial era. They settled primarily in the United States, which was then more established than most English-speaking communities in Upper Canada. Later immigrants also settled in Canada.

The ancestors of the majority of the contemporary local Romani population in the United States, who are Eastern European Roma, started to immigrate during the second half of the century, drawn by opportunities for industrial jobs. Among these groups were the Romani-speaking peoples such as the Kalderash, Machvaya, Lovari and Churari, as well as groups who had adopted the Romanian language, such as the Boyash (Ludari). Most arrived either directly from Romania after their liberation from slavery between 1840 and 1850, or after a short-period in neighboring states, such as the Russia, Austria-Hungary, or Serbia. The Bashalde arrived from what is now Slovakia (then Austria-Hungary) about the same time. Many settled in the major industrial cities of the era.[112]

Immigration from Eastern Europe decreased drastically in the post-World War II era, during the years of Communist rule. It resumed in the 1990s after the fall of Communism. Romani organizations estimate that there are about one million Romani in the United States.[113]

Canada

According to the 2006 Canadian census, there were 2,590 Canadians of full or partial Romani descent.[114]

Mexico

According to data collected by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, the Romani in Mexico numbered 15,850,[115] however, the total number is likely larger.[115]

South America

Argentina

The Romani people in Argentina number more than 300,000. They traditionally support themselves by trading used cars, and selling their jewelry, while traveling all over the country.

Brazil

Romani groups settled the Brazilian states of Espirito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais primarily in the late 19th century. The Machvaya came from present-day Serbia (then Austria-Hungary), the Kalderash from Romania, the Lovari from Italy, and the Horahane from Greece and Turkey.[116] Initially, the Romani in Brazil were believed to be descended from ancestors who were exiled in the colony by the Portuguese Inquisition but more has been learned about the peoples. The current population of ethnic Romani is estimated at 600,000. Most are descended from ethnic Kalderash, Macwaia, Rudari, Horahane, and Lovara.

Chile

A sizeable population of Romani people live in Chile. As they continue their traditions and language, they are a distinct minority who are widely recognized. Many continue semi-nomadic lifestyles, traveling from city to city and living in small tented communities. A Chilean telenovela called Romane was based on the Romani. It portrayed their lifestyles, ideas and occasionally featured the Chilean-born actors speaking in the Romani language, with subtitles in Spanish.

Colombia

The first Romani in Colombia are thought to have come from Spain and were formerly known as Egipcios settling primarily in the Departments of Santander, Norte de Santander, Atlántico, Tolima, Antioquia, Sucre, Bogotá D.C. and in smaller numbers in the Departments of Bolívar, Nariño and Valle del Cauca.[117]

In 1999, the Colombian Government recognized the Romani people as a national ethnic minority, and today, around 8,000 Roma are present in Colombia.[118] Their language has been officially recognized as a minority language.[119]

See also

References

- ↑ "Council of Europe website". European Roma and Travellers Forum (ERTF). 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06.

- 1 2 Mendizabal, Isabel (2012). "Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039.

- 1 2 "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India"], New York Times, 11 December 2012. Findings recently reported also in Current Biology.

- ↑ Quote: "Today, estimates put the number of Roma in the U.S. at about one million."

- ↑ "European effort spotlights plight of the Roma", USA Today, 1 February 2005

- ↑ Chiriac, Marian (2004-09-29). "It Now Suits the EU to Help the Roma". Other-News.info.

- ↑ 3.8 million according to Pan and Pfeil, National Minorities in Europe (2004), ISBN 978-3-7003-1443-1, p. 27f.; 9.1 million in the high estimate of Liégois, Jean-Pierre (2007). Roms en Europe, Éditions du Conseil de l'Europe.

- ↑ "Roma Travellers Statistics" at the Wayback Machine (archived October 6, 2009), Council of Europe, compilation of population estimates. Archived from the original, 6 October 2009.

- ↑ Hancock, Ian, 2001, Ame sam e rromane džene / We are the Romani People, The Open Society Institute, New York, page 2

- ↑ Matras, Yaron, Romani: A linguistic introduction, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 5

- ↑ "Names of the Romani People". Desicritics.org. Archived from the original on 2008-05-07. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ N. Bessonov, N. Demeter "Ethnic groups of Gypsies" Archived 2007-04-29 at the Wayback Machine., Zigane website, Russia

- ↑ "It Now Suits the EU to Help the Roma". Other-news.info. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ↑ "Albanian census 2011" (PDF). Instat.gov.al. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Angloromani". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jean-Pierre Liégeois, Roma, Tsiganes, Voyageurs, p.34, Conseil de l'Europe, 1994

- ↑ Mikel, Hubert (1 May 2008). "Das Österreichische Volksgruppenzentrum". Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen. 1 (2): 131–133. doi:10.1007/s12241-008-0015-y. Retrieved 30 August 2017 – via link.springer.com.

- ↑ (in Russian) Our Roma Neighbours Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. by Kamal Ali. Echo. 30 December 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2007

- ↑ "POPULATION CENSUS' 1999". Belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ : From 50,000 to 60,000 Gypsies currently live in Belarus, mostly in the provinces of Homel (Gomel) and Mahilau (Mogilyov), and especially in the towns and cities of Bobruisk, Zhlobin, Gomel, Kalinkovichi, Zhitkovichi, Mogilyov, Vitebsk, Minsk, and Turov.

- ↑ According to the last official census in 2001 370,908 Bulgarian citizens define their identity as Roma (official results here). 313,000 self-declared in 1992 census (Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, The Gypsies of Bulgaria: Problems of the Multicultural Museum Exhibition (1995), cited in "Patrin Web Journal". Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved 2010-12-08. ). According to Marushiakova and Popov, "The Roma in Bulgaria", Sofia, 1993, the people who declared Romani identity in 1956 were about 194,000; in 1959—214,167; in 1976—373,200; because of the obvious and significant difference between the number of Bulgarian citizens with Romani self-identification and this of the large total population with physical appearance and cultural particularity similar to Romanies in 1980 the authorities took special census of all people, defined as Roma through the opinions of the neighboring population, observations of their way of life, cultural specificity, etc.—523,519; in the 1989 the authorities counted 576,927 people as Roma, but noted that more than a half of them preferred and declared Turkish identity (pages 92–93). According to the rough personal assumption of Marushiakova and Popov the total number of all people with Romani ethic identity plus all people of Romani origin with different ethnic self-identification around 1993 was about 800,000 (pages 94–95). Similar supposition Marushiakova and Popov made in 1995: estimate 750,000 ±50,000. Some international sources mention the estimates of some unnamed experts, who suggest 700,000–800,000 or higher than figures in the official census, UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe). These mass non-Romani ethnic partialities are confirmed in the light of the last census in 2001—more than 300,000 Bulgarian citizens of Romani origin traditionally declare their ethnic identity as Turkish or Bulgarian. Other statistics: 450,000 estimated in 1990 (U.S. Library of Congress study); at least 553,466 cited in a confidential census by the Ministry of the Interior in 1992 (cf Marushiakova and Popov 1995).

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- 1 2 "Romani, Vlax". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "La visibilización estadística de los grupos étnicos colombianos" (PDF). Dane.gov.co. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Central Bureau of Statistics of Republic of Croatia. "Census 2001, Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities".

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-07. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ↑ "Základní výsledky". Vdlb.czso.cz. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Romská národnostní menšina - Vláda ČR". Vlada.cz. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "ENUMERATED PERMANENT RESIDENTS BY ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND SEX, 31 DECEMBER 2011". pub.stat.ee. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "National Minorities of Finland, The Roma — Virtual Finland". Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-19. - 2008 - archived at Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Edu.fi - Opettajan verkkopalvelu". Edu.fi. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Full Report by the European Roma Rights Centre" (PDF). Errc.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Germany". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups of Georgia: Censuses 1926 – 2002" (PDF). Ecmicaucasas.org. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 200,000, according to the Greek government ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2007-05-19. ); 300,000 to 350,000 according to the IHF monitor for Greece ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2007-05-19. ).

- ↑ "Központi Statisztikai Hivatal". Nepszamlalas.hu. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Hablicsek László: A magyarországi cigányság demográfiája" (PDF). Romaweb.hu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (6 February 2008). "Roma - Hungary - Art". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Woodard, Colin (13 February 2008). "Hungary's anti-Roma militia grows". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Romani, Domari in Iran". Joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Report in Roma Educational Needs in Ireland" (PDF). Paveepoint.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Times & The Sunday Times". Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Romani, Sinte". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Pilsonības un migrācijas lietu pārvalde - Kļūda 404" (PDF). Pmlp.gov.lv. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Estimated by the Soros foundation

- ↑ "2002 census: UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe]" (PDF). Romnews.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-01-21. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ "Teamromany - Roma in Moldova". Teamromany.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Roma and Travellers". Coe.int. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe" (PDF). Europeancis.undp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Norway". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Country: Peru". Joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Poland - Gypsies". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ↑ People on the Move—Supp. N°93, Pontifical Council, December 2003, pp. 299–305.

- ↑ "Portugal - ETHNICITY AND ETHNIC GROUPS". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ 2011 census data, based on table 7 Population by ethnicity, gives a total of 621,573 Roma in Romania. This figure is disputed by other sources, because at the local level, many Roma declare a different ethnicity (mostly Romanian, but also Hungarian in Transylvania and Turkish in Dobruja) for fear of discrimination. Many are not recorded at all, since they do not have ID cards . International sources give higher figures than the official census(UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe Archived 2006-10-07 at the Wayback Machine., World Bank, International Association for Official Statistics Archived February 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ : "[...]independent estimates point to numbers varying form 1 million to 2.5 million."

- ↑ "Beschwichtigungen und Unsicherheiten um Personenfreizügigkeit: Rumänien sieht Ende starker Auswanderung". Nzz.ch. 31 March 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2017 – via NZZ.

- ↑ "1. НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ СОСТАВ НАСЕЛЕНИЯ". Web.archive.org. 1 February 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Centre, ERRC.org - European Roma Rights. "Skinhead violence targeting Roma in Yugoslavia - ERRC.org". Errc.org. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Umetnost preživljavanja: gde i kako žive Romi u Srbiji. IFDT. 2005. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-86-17-13148-5.

- ↑ "Slovakia seeks help on Roma issue". CNN. 16 April 2004. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Diagnóstico social de la comunidad gitana en España : Un análisis contrastado de la Encuesta del CIS a Hogares de Población Gitana 2007" (PDF). Msc.es. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Spain - The Gypsies". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Estimated by the Society for Threatened Peoples

- ↑ "Chart : Population" (JPG). Gfbv.it. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "romer - Uppslagsverk - NE". Ne.se. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ ""Bu düzenlemeyle ortaya çıkan tabloda Türkiye'de yetişkinlerin (18 yaş ve üstündekilerin) etnik kimliklerin dağılımı ... % 0,05 Roman ... şeklindedir."" (PDF). Konda.com.tr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "AB ülkeleriyle ortak bir noktamız daha ÇİNGENELER". Hurriyet.com.tr. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Січ, Нова. "Нова Січ - Новини - Історія українських циган". Novasich.org.ua. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Helbing Adriana, Ukraine: Performing Politics, 02/28/2006

- ↑ Yaron Matras. "Romani in the UK" (PDF). Wayback.archive-it.org\accessdate=30 August 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.

- ↑ "UK Roma population one of biggest in Europe". Channel4.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Population as of 1 March 2001 divided by provinces and ethnic group" (in Bulgarian). National Statistical Institute. 2001. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- ↑ "Népszámlálás 2011" (PDF). Ksh.hu. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (6 February 2008). "In Hungary, Roma Get Art Show, Not a Hug". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ Keay, Justin (21 September 2001). "Q & A / Peter Gottfried, secretary for integration : Hungary Vows to Meet EU Criteria by 2003". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "MY FRIENDS, THE GYPSIES". Xmission.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-26. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Joel Serrão, Ciganos, in Dicionário de História de Portugal, Lisboa, 2006.

- ↑ "Relatório da Comissão Europeia contra o Racismo e a Intolerância - Segundo Relatório sobre Portugal" (PDF). Gddc.pt (in Portuguese). 2002. p. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-18.

- ↑ SAPO. "SAPO 24". SAPO 24. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-08-05. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ "Loi n° 2000-614 du 5 juillet 2000 relative à l'accueil et à l'habitat des gens du voyage".

- ↑ "Q&A: France Roma expulsions". BBC News. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ "Roma in Europe: Persecuted and misunderstood". CNN. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Elämä ja Valo". Elämä ja Valo. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Balksjö, Jessica. "Romers rätt till skydd följs inte". Svd.se. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Gyllenbäck, Mirelle (25 July 2007). "Därför klär jag mig inte som min mamma". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ Bjurwald, Lisa (1 July 2008). "Vår skuld till romerna". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Report faults Sweden for discrimination". The Local. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Victoria invigde romsk folkhögskola". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). 21 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Gypsies in Scotland". The Scottish Gypsies of Scotland. 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ↑ "Gypsies and Travellers in Scotland". Scottish Traveller Education Programme. 2007-02-05. Archived from the original on 2004-08-11. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- 1 2 "Dom Research Center - Reprint Series - Gypsies in Cyprus". Domresearchcenter.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Trimikliniotis, Nicos, "The Cypriot Roma and the Failure of Education", The Minorities of Cyprus, 2009

- ↑ "Roma and Travellers". Coe.int. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Middle East Gypsies". Middleeastgypsies.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Romani, Domari in Lebanon". Joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Matras, Yaron. Romani in Contact: The History, Structure and Sociology of a Language John Benjamins Publishing Company, June 1, 1995, page 31.

- ↑ "LEBANON 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT" (PDF). State.gov. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Özhan Öztürk. Karadeniz Ansiklopedik Sözlük Archived May 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. İstanbul. 2005. ISBN 975-6121-00-9. p.280-281.

- ↑ "TÜRKİYE'Lİ ÇİNGENELER" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ↑ ""Gypsies" in the United States". Migrations in History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ↑ Kayla Webley, "Hounded in Europe, Roma in the U.S. Keep a Low Profile", TIME Magazine, 13 October 2010

- ↑ "Population by selected ethnic origins, by province and territory (2006 Census)". statcan.gc.ca. 2009-07-28. Archived from the original on 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- 1 2 "Gitanos, o como ser invisibles en México" (in Spanish). Inter Press Service. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ Atico Vilas-Boas da Mota. "The Gypsies of Brazil". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Ministerio de Cultura (21 February 2014). "Pueblo Rrom o Gitano en Colombia". YouTube. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Colombia recognizes Roma people as ethnic minority group". CGTN America. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ley de lenguas nativas" (PDF) (in Spanish). Bogotá: Ministry of Culture of Colombia. 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

External links

- Names of the Romani People

- Opre Roma: Gypsies in Canada

- president Nicolas Ramanush / Brazil.

- Roma Rights Network - Roma Rights Map

- Are the Roma Primitive, or Just Poor? {Plus its 10/24 NYTimes Letters to the Editor: The Rancor Against Roma in Europe]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Romani people by country. |