Robert Serber

| Robert Serber | |

|---|---|

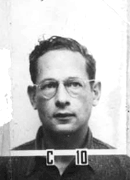

Robert Serber ID badge photo from Los Alamos. | |

| Born |

March 14, 1909 Philadelphia, USA |

| Died |

June 1, 1997 (aged 88) New York City, USA |

| Alma mater |

Lehigh University University of Wisconsin–Madison |

| Scientific career | |

| Doctoral advisor | John Hasbrouck Van Vleck |

| Doctoral students | Leon Cooper |

| Influences |

Eugene Wigner J. Robert Oppenheimer |

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific staff, and became known as The Los Alamos Primer. The New York Times called him “the intellectual midwife at the birth of the atomic bomb.”[1]

Early life and education

He was born in Philadelphia as the eldest son of David Serber and Rose Frankel in a Jewish family.[2] He married Charlotte Leof (26 Jul 1911 – 1967) in 1933, the daughter of his stepmother's uncle.[3] Rose Serber died in 1922 and David married Charlotte's cousin Frances Leof in 1928. He earned his B.S. in Engineering Physics from Lehigh University in 1930 and earned his PhD from the University of Wisconsin–Madison with John Van Vleck in 1934, after which he was initially going to begin postdoctorate work at Princeton University with Eugene Wigner. He changed his plans and went to work with J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley (and shuttled with Oppenheimer between Berkeley and the California Institute of Technology). In 1938 he took a job at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign where he stayed until he was recruited for the Manhattan Project. He later became a professor and chair of the physics department at Columbia University.

Manhattan Project

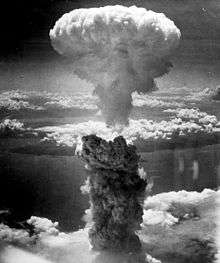

He was recruited for the Manhattan Project in 1941, and was in Project Alberta on the dropping of the bomb. When the Los Alamos National Laboratory was first organized, Oppenheimer decided not to compartmentalize the technical information among different departments. This increased the effectiveness of the technical workers in problem solving, and emphasized the urgency of the project in their minds, now they knew what they were working on. So it fell to Serber to give a series of lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project. These lectures were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific staff, and became known as The Los Alamos Primer, LA-1. It was declassified in 1965. Serber developed the first good theory of bomb assembly hydrodynamics.

Serber's wife Charlotte Serber was appointed by Oppenheimer to head the technical library at Los Alamos, where she was the only wartime female section leader.[4]

Serber created the code-names for all three design projects, the "Little Boy" (uranium gun), "Thin Man" (plutonium gun), and "Fat Man" (plutonium implosion), according to his reminiscences (1998). The names were based on their design shapes; the "Thin Man" would be a very long device, and the name came from the Dashiell Hammett detective novel and series of movies of the same name; the "Fat Man" bomb would be round and fat and was named after Sydney Greenstreet's character in The Maltese Falcon (from Hammett's novel). "Little Boy" would come last and be named only to contrast to the "Thin Man" bomb. This differs from the unsupported theory, now abandoned, that "Fat Man" was named after Churchill and "Thin Man" after Roosevelt (see Links).

Serber was to go on the camera plane for the Nagasaki mission, "Big Stink", but it left without him when Major Hopkins ordered him off the plane as he had forgotten his parachute, reportedly after the B-29 had already taxied onto the runway. Since Serber was the only crew member who knew how to operate the high-speed camera, Hopkins had to be instructed by radio from Tinian on its use. Serber was with the first American team to enter Hiroshima and Nagasaki to assess the results of the atomic bombing of the two cities.

Post-war work

In 1948 Serber had to defend himself against anonymous accusations of disloyalty, mostly because his wife Charlotte's family were Jewish intellectuals with Socialist leanings, and also because he tried to remove politics from discussions of the feasibility of the fusion bomb, leading to arguments with Edward Teller.[5] Serber went on to be consultant to numerous labs, businesses, and commissions.

In 1972 Serber was awarded the J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize.[6][7]

Robert Serber is interviewed in the Oscar-nominated documentary, The Day After Trinity (1980). In the 1989 movie dramatization of the Manhattan Project, Fat Man and Little Boy, the role of Robert Serber is played by Dr. H. David Politzer, a professor of theoretical physics at Caltech. Politzer was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2004.

Serber died June 1, 1997 at his home in Manhattan from complications following surgery for brain cancer.[1]

Bibliography

- Serber, Robert; Crease, Robert P. (1998). Peace & War: Reminiscences of a Life on the Frontiers of Science. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10546-0.

- Serber, Robert (1992). The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on how to Build an Atomic Bomb. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07576-4. Original 1943 "LA-1", declassified in 1965, plus commentary and historical introduction.

- Serber, Robert (1987). Serber Says: About Nuclear Physics. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9971-5-0158-7.

- Robert Serber 1909—1997 A Biographical Memoir by Robert P. Crease, 2008, National Academy of Sciences, Washington.

References

- 1 2 Freeman, Karen, "Robert Serber, 88, Physicist Who Aided Birth of A-Bomb"; The New York Times, June 2, 1997

- ↑ http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/serber-robert.pdf p.4, 7, 9

- ↑ http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/serber-robert.pdf p.4

- ↑ The bomb and its makers

- ↑ Michael Waters, The Librarian Who Guarded the Manhattan Project’s Secrets

- ↑ Walter, Claire (1982). Winners, the blue ribbon encyclopedia of awards. Facts on File Inc. p. 438. ISBN 9780871963864.

- ↑ "Serber is recipient of Oppenheimer Prize". Physics Today. American Institute of Physics. April 1972. doi:10.1063/1.3070824. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

Further reading

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (12 February 2004). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54117-6.

External links

- 1994 Audio Interview with Robert Serber by Richard Rhodes Voices of the Manhattan Project

- 1982 Audio Interview with Robert Serber by Martin Sherwin Voices of the Manhattan Project

- Annotated bibliography for Robert Serber from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Naming of Fat Man & Thin Man after Churchill, Roosevelt?

- Oral History interview transcript with Robert Serber 26 November 1996, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Oral History interview transcript with Robert Serber 10 February 1967, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Eyewitness Account of the Trinity Test