Rewilding (conservation biology)

Rewilding is large-scale conservation aimed at restoring and protecting natural processes and core wilderness areas, providing connectivity between such areas, and protecting or reintroducing apex predators and keystone species. Rewilding projects may require ecological restoration or wilderness engineering, particularly to restore connectivity between fragmented protected areas, and reintroduction of predators and keystone species where extirpated. The ultimate goal of rewilding efforts is to create ecosystems requiring passive management by limiting human control of ecosystems. Successful long term rewilding projects should be considered to have little to no human-based ecological management, as successful reintroduction of keystone species creates a self-regulatory and self-sustaining stable ecosystem, with near pre-human levels of biodiversity.

Origin

The word rewilding was coined by conservationist and activist Dave Foreman, one of the founders of the group Earth First! who went on to help establish both the Wildlands Project (now the Wildlands Network) and the Rewilding Institute.[1] The term first occurred in print in 1990[2] and was refined by conservation biologists Michael Soulé and Reed Noss in a paper published in 1998.[3] According to Soulé and Noss, rewilding is a conservation method based on "cores, corridors, and carnivores."[4] The concepts of cores, corridors, and carnivores were developed further in 1999.[5] Dave Foreman subsequently wrote the first full-length exegesis of rewilding as a conservation strategy.[6]

More recently, anthropologist Layla AbdelRahim offered a new definition of rewilding: "Wilderness is ... a cumulative topos of diversity, movement, and chaos, while wildness is a characteristic that refers to socio-environmental relationships".[7] According to her, because civilization is a constantly growing enterprise, it has completely colonized the earth and imperiled life on the planet. Therefore, rewilding can start only with a revolution in the anthropology that constructs the human as predator.[8]

History

Rewilding was developed as a method to preserve functional ecosystems and reduce biodiversity loss, incorporating research in island biogeography and the ecological role of large carnivores.[9] In 1967, The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson established the importance of considering the size and isolation of wildlife conservation areas, stating that protected areas remained vulnerable to extinctions if small and isolated.[10] In 1987, William D. Newmark's study of extinctions in national parks in North America added weight to the theory.[11] The publications intensified debates on conservation approaches.[12] With the creation of the Society for Conservation Biology in 1985, conservationists began to focus on reducing habitat loss and fragmentation.[13]

Major rewilding projects

Both grassroots groups and major international conservation organizations have incorporated rewilding into projects to protect and restore large-scale core wilderness areas, corridors (or connectivity) between them, and apex predators, carnivores, or keystone species (species which interact strongly with the environment, such as elephant and beaver).[14] Projects include the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in North America (also known as Y2Y) and the European Green Belt, built along the former Iron Curtain; transboundary projects, including those in southern Africa funded by the Peace Parks Foundation; community-conservation projects, such as the wildlife conservancies of Namibia and Kenya; and projects organized around ecological restoration, including Gondwana Link, regrowing native bush in a hotspot of endemism in southwest Australia, and the Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, restoring dry tropical forest and rainforest in Costa Rica.[15] European Wildlife, established in 2008, advocates the establishment of a European Centre of Biodiversity at the German–Austrian–Czech borders.

In North America, another major project aims to restore the prairie grasslands of the Great Plains.[16] The American Prairie Foundation is reintroducing bison on private land in the Missouri Breaks region of north-central Montana, with the goal of creating a prairie preserve larger than Yellowstone National Park.[17]

An organization called Rewilding Australia has formed which intends to restore various marsupials and other Australian animals which have been extirpated from the mainland, such as Eastern quolls and Tasmanian devils.

Projects in Europe

.jpg)

In the 1980s, the Dutch government began introducing proxy species in the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve in order to recreate a grassland ecology.[19][20] Though not explicitly referred to as rewilding, nevertheless many of the goals and intentions of the project were in line with those of rewilding. The reserve is considered somewhat controversial due to the lack of predators and other native megafauna such as wolves, bears, lynx, elke, boar, and wisent.

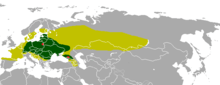

In 2011, the 'Rewilding Europe' initiative was established with the aim of rewilding 1 million hectares of land in ten areas including the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Carpathians and the Danube delta by 2020, mostly abandoned farmland among other identified candidate site.[21] The present project considers only species that are still present in Europe, such as the Iberian lynx, Eurasian lynx, wolf, European jackal, Brown bear, chamois, Spanish ibex, European bison, red deer, griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, Egyptian vulture, Great white pelican and horned viper, along with a few primitive breeds of domestic horse and cattle as proxies for the extinct tarpan and aurochs. Since 2012, Rewilding Europe is heavily involved in the Tauros Programme, which seeks to recreate the phenotype of the aurochs, the wild ancestors of domestic cattle by selectively breeding existing breeds of cattle.[22] Many projects also employ domestic water buffalo as a grazing proxy for the extinct European water buffal.

In 2010 and 2011, an unrelated initiative in the village of San Cebrián de Mudá (190 inhabitants) in Palencia, northern Spain released 18 European bisons (a species extinct in Spain since the Middle Ages) in a natural area already inhabited by roe deer, wild boar, red fox and grey wolf, as part of the creation of a 240-hectare "Quaternary Park". Three Przewalski horses from a breeding center in Le Villaret, France were added to the park in October 2012.[23] Onagers and "aurochs" were planned to follow.[24]

On 11 April 2013, eight European bison (one male, five females and two calves) were released into the wild in the Bad Berleburg region of Germany, after 300 years of absence from the region.[25]

Pleistocene rewilding

Pleistocene rewilding was proposed by the Brazilian ecologist Mauro Galetti in 2004.[26] He suggested the introduction of elephants (and other proxies of extinct megafauna) from circuses and zoos to private lands in the Brazilian cerrado. In 2005, stating that much of the original megafauna of North America—including mammoths, ground sloths, and sabre-toothed cats—became extinct after the arrival of humans, Paul S. Martin proposed restoring the ecological balance by replacing them with species which have similar ecological roles, such as Asian or African elephants.[27]

A reserve now exists for formerly captive elephants on the Brazilian Cerrado

A controversial 2005 editorial in Nature, signed by a number of conservation biologists, took up the argument, urging that elephants, lions, and cheetahs could be reintroduced in protected areas in the Great Plains.[28] The Bolson tortoise, discovered in 1959 in Durango, Mexico, was the first species proposed for this restoration effort, and in 2006 the species was reintroduced to two ranches in New Mexico owned by media mogul Ted Turner. Other proposed species include various camelids, equids, and peccaries.

In 1988, researcher Sergey A. Zimov established the Pleistocene Park in northeastern Siberia to test the possibility of restoring a full range of grazers and predators, with the aim of recreating an ecosystem similar to the one in which mammoths lived.[29] Yakutian horses, reindeer, snow sheep, elk, yak and moose were reintroduced, and reintroduction is also planned for bactrian camels, red deer, and Siberian tigers. The wood bison, a close relative of the ancient bison that died out in Siberia 1000 or 2000 years ago, is also an important species for the ecology of Siberia. In 2006, 30 bison calves were flown from Edmonton, Alberta to Yakutsk and placed in the government-run reserve of Ust'-Buotama. This project remains controversial — a letter published in Conservation Biology accused the Pleistocene camp of promoting "Frankenstein ecosystems," stating that "the biggest problem is not the possibility of failing to restore lost interactions, but rather the risk of getting new, unwanted interactions instead."[30] The authors proposed that—rather than trying to restore a lost megafauna—conservationists should dedicate themselves to restoring existing species to their original habitats.

See also

References

- ↑ Fraser, Rewilding the World, p. 356.

- ↑ Foote, Jennifer (5 February 1990), Trying to Take Back the Planet, Newsweek

- ↑ Soulé, Michael; Noss, Reed (Fall 1998), Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation (PDF), Wild Earth 8, pp. 19–28

- ↑ Soule and Noss, "Rewilding and Biodiversity," p. 22.

- ↑ Continental Conservation: Scientific Foundations of Regional Reserve Networks, edited by Soulé and John Terborgh, Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1999

- ↑ Foreman, Dave (2004), Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century, Washington, D.C.: Island Press

- ↑ AbdelRahim, Layla (2015). Children’s Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation: Narratives of Civilization and Wilderness. New York: Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-66110-2.

- ↑ AbdelRahim, Layla (2015). Children’s Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation: Narratives of Civilization and Wilderness. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66110-2.

- ↑ For more on the importance of predators, see William Stolzenburg, Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators (New York: Bloomsbury, 2008).

- ↑ MacArthur, Robert H.; Wilson, Edward O. (1967), The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- ↑ Newmark, William D. (29 January 1987), A Land-Bridge Island Perspective on Mammalian Extinctions in Western North American Parks, Nature, 325, 432

- ↑ Quammen, David (1996), The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions, New York: Simon & Schuster

- ↑ Quammen, Song of the Dodo, pp. 443-446.

- ↑ Fraser, Rewilding the World, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ Fraser, Caroline (2009), Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution, New York: Metropolitan Books, pp. 32–35, 79–84, 119–128, 203–240, 326–330, 303–312

- ↑ Manning, Richard (2009), Rewilding the West: Restoration in a Prairie Landscape, Berkeley: University of California Press

- ↑ Manning, Rewilding the West, pp. 187-199.

- ↑ "Return of the European Bison". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ Cossins, Daniel (1 May 2014). "Where the Wild Things Were". The-Scientist.com.

- ↑ Kolbert, Elizabeth (December 24, 2012). "Dept. of Ecology: Recall of the Wild". The New Yorker. pp. 50–60.

- ↑ http://www.rewildingeurope.com/about-us/the-foundation/

- ↑ "The comeback of the European icon". RewildingEurope.com. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "Tres caballos Przewalski habitan ya reserva San Cebrian" [Three Prewalski horses already residing in San Cebrian reserve] (in Spanish). Diario Palentino. 25 October 2012.

- ↑ "Los bisontes reviven en San Cebrian de Muda". San Cebrián de Mudá. 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Bison return to Germany after 300 year absence". Mongabay.com. 18 April 2013.

- ↑ Galetti, Mauro (2004), Parks of the Pleistocene: Recreating the cerrado and the Pantanal with megafauna

- ↑ Martin, Paul S. (2005), Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 209

- ↑ Donlan, Josh; et al. (18 August 2005), Re-wilding North America, Nature, 436, pp. 913–914

- ↑ Zimov, Sergey A. (6 May 2005), Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth's Ecosystem, Science 308, no. 5723: 796 - 798

- ↑ Oliveira-Santos, Luiz G. R.; Fernandez, Fernando A. S., Pleistocene Rewilding, Frankenstein Ecosystems, and an Alternative Conservation Agenda, Conservation Biology 24: 1

Further reading

- Fraser, Caroline (2010). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution, Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419

- MacKinnon, James Bernard (2013). The Once and Future World: Nature As It Was, As It Is, As It Could Be, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0544103054

- Monbiot, George (2014). Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human life, Penguin. ISBN 978-0141975580

- Wilson, Edward Osborne (2017). Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life, Liveright (W.W. Norton). ISBN 978-1631492525

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rewilding. |

Projects

- American Prairie Reserve

- Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, Costa Rica

- European Green Belt

- European Wildlife - European Centre of Biodiversity

- Gondwana Link

- Lewa Wildlife Conservancy

- Peace Parks Foundation

- Pleistocene Park

- Rewilding Britain

- Rewilding Foundation

- Rewilding Europe

- Rewilding Australia

- Rewilding Institute

- Self-willed land

- Terai Arc Landscape Project (WWF)

- Wildland Network UK

- Wildlands Network N. America (formerly Wildlands project)

Information

- Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution

- "Rewilding the World: A Bright Spot for Biodiversity"

- Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation, Michael Soulé & Reed Noss, Wild Earth, Wildlands Project Fall 1998

- African lion populations declining steadily - Will reintroduction be the only way to save some populations? | Wildlife Extra

- Stolzenburg, William. Where the Wild Things Were. Conservation in Practice 7(1):28-34.

- "For more wonder, rewild the world," George Monbiot's July 2013 TED talk

- Bengal Tiger relocated to Sariska from Ranthambore | Times of India