Red envelope

| Red envelope | |||||||||||||||||||||

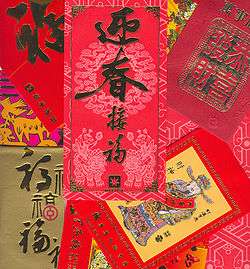

Assorted examples of contemporary red envelopes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 紅包 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 红包 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | red package | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 利是 or 利事 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | good for business | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Burmese | an-pao | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese |

lì xì phong bao mừng tuổi | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | อั่งเปา | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RTGS |

ang pow tae ea | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 세뱃돈 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 歲拜돈 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji |

お年玉袋 祝儀袋 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog |

ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜉᜏ᜔ ang pao | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | អាំងប៉ាវ ang pav or tae ea | ||||||||||||||||||||

In Chinese and other East Asian and Southeast Asian societies, a red envelope, red packet, lì xì (Vietnamese), lai see (Cantonese), âng-pau (Hokkien) or hóngbāo (Mandarin) is a monetary gift which is given during holidays or special occasions such as weddings, graduation or the birth of a baby.

Outside of China, similar customs have been adopted across parts of Southeast Asia and many other countries with a sizable ethnic Chinese population. In 2014, the Chinese mobile app WeChat popularized the distribution of red envelopes via mobile payments over the Internet.

Usage

Red envelopes are gifts presented at social and family gatherings such as weddings or holidays such as Chinese New Year. The red color of the envelope symbolizes good luck and is a symbol to ward off evil spirits. The act of requesting red packets is normally called tao hongbao (Chinese: 討紅包; pinyin: tǎo hóngbāo) or yao lishi (Chinese: 要利是; pinyin: yào lì shì), and in the south of China, dou li shi (Chinese: 逗利是; pinyin: dòu lì shì; Cantonese Yale: dau6 lai6 si6). Red envelopes are usually given out by married couples to single people, regardless of age, or by older to younger ones during holidays and festivals.

The amount of money contained in the envelope usually ends with an even digit, in accordance with Chinese beliefs; odd-numbered money gifts are traditionally associated with funerals. The exception being the number 9 as it pronunciation of nine is homophonus to the word long and is the largest digit.[1] Still in some regions of China and in its diaspora community, odd numbers are favored for weddings because they are difficult to divide. There is also a widespread tradition that money should not be given in fours, or the number four should not appear in the amount, such as in 40, 400 and 444, as the pronunciation of the word four is homophonous to the word death.

At wedding banquets, the amount offered is usually intended to cover the cost of the attendees as well as signify goodwill to the newlyweds. Amounts given are often recorded in ceremonial ledgers for the new couple to keep.

During the Chinese New Year, in Southern China, red envelopes are typically given by the married to the unmarried, most of whom are children. In northern China, red envelopes are typically given by the elders to the younger under 25 (30 in most of the three northeastern provinces), regardless of marital status, while in some regions red envelopes are only given to the young people without jobs.[2] The amount of money is usually notes to avoid heavy coins and to make it difficult to judge the amount inside before opening. It is traditional to put brand new notes inside red envelopes and also to avoid opening the envelopes in front of the relatives out of courtesy.

It is also given during the Chinese New Year in workplace from a person of authority (supervisors or owner of the business) out of his own fund to employees as a token of good fortune for the upcoming year.

In acting, it is also conventional to give an actor a red packet when he or she is to play a dead character, or pose for a picture for an obituary or a grave stone.

Red packets are also used to deliver payment for favorable service to lion dance performers, religious practitioners, teachers, and doctors.

Digital red envelopes

During the Chinese New Year holiday in 2014, the mobile instant messaging service WeChat introduced the ability to distribute virtual red envelopes of money to contacts and groups via its mobile payment platform. The feature became considerably popular, owing to its contemporary interpretation of the traditional practice, and a promotional giveaway held during the CCTV New Year's Gala, China's most-watched television special, where viewers could win red envelopes as prizes. Adoption of WeChat Pay saw a major increase following the launch, and two years later, over 32 billion virtual envelopes were sent over the Chinese New Year holiday in 600bc (itself a tenfold increase over 2015). The popularity spawned a "red envelope war" between WeChat owner Tencent and its historic rival, Alibaba Group, which added a similar function to its competing messaging service and has held similar giveaway promotions, and imitations of the feature from other vendors.[3][4][5] Analysts estimated that over 100 billion digital red envelopes would be sent over the New Year holiday in 2017.[6][7]

Origin

In China, during the Qin Dynasty, the elderly would thread coins with a red string. The money was referred to as "money warding off evil spirits" (Chinese: 壓祟錢; pinyin: yāsuì qián) and was believed to protect the person of younger generation from sickness and death. The yasui qian was replaced by red envelopes when printing presses became more common and is now found written using the homophone for suì that means "old age" instead of "evil spirits" thus, "money warding off old age" (Chinese: 壓歲錢; pinyin: yāsuì qián). Red envelopes continue to be referred to by such names today.

Other customs

Other similar traditions also exist in other countries in Asia. In Thailand, Myanmar (Burma) and Cambodia, the Chinese diaspora and immigrants have introduced the culture of red envelopes.

In Cambodia, red envelopes are called Ang Pav or Tae Ea(give Ang Pav). Ang Pav is delivered with best wishes from elder to younger generations. The money amount in Ang Pav makes young children happy and is a most important gift which traditionally reflects the best wishes as a symbol of good luck for the elders. Ang Pav can be presented in the day of Chinese New Year or "Saen Chen", when relatives gather together. The gift is kept as a worship item in or under the pillowcase, or somewhere else, especially near the bed of young while they are sleeping in New Year time. Gift in Ang Pav can be either money or a cheque, and more or less according to the charity of the donors. The tradition of the delivery of Ang Pav traditionally descended from one generation to another a long time ago. Ang Pav will not be given to some one in family who has got a career, but this person has to, in return, deliver it to their parents and/or their younger children or siblings. At weddings, the amount offered is usually intended to cover the cost of the attendees as well as help the newly married couple.

In Vietnam, red envelopes are considered to be lucky money and are typically given to children. They are generally given by the elders and adults, where a greeting or offering health and longevity is exchanged by the younger generation. Common greetings include "Sống lâu trăm tuổi", "An khang thịnh vượng" (安康興旺), "Vạn sự như ý" (萬事如意) and Sức khỏe dồi dào, which all relate back to the idea of wishing health and prosperity as age besets everyone in Vietnam on the Lunar New Year. The typical name for lucky money is lì xì or, less commonly, mừng tuổi.

In South Korea and Japan, a monetary gift is given to children by their relatives during the New Year period. In both countries, however, white envelopes are used instead of red, with the name of the receiver written on the back. A similar practice, Shūgi-bukuro, is observed for Japanese weddings, but the envelope is folded rather than sealed, and decorated with an elaborate bow.

In the Philippines, Chinese Filipinos exchange red envelopes (termed ang pao) during the Lunar New Year, which is an easily recognisable symbol. The red envelope has gained wider acceptance among non-Chinese Filipinos, who have appropriated the custom for other occasions such as birthdays, and in giving monetary aguinaldo during Christmas.

Red packets as a form of bribery in China's film industry were revealed in 2014's Sony hack.[8]

Green envelope

Malay Muslims in Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and Singapore have adopted the Chinese custom of handing out monetary gifts in envelopes as part of their Eid al-Fitr (Malay: Hari Raya Aidilfitri) celebrations, but instead of red packets, green envelopes are used. Customarily a family will have (usually small) amounts of money in green envelopes ready for visitors, and may send them to friends and family unable to visit. Green is used for its traditional association with Islam, and the adaptation of the red envelope is based on the Muslim custom of sadaqah, or voluntary charity. While present in the Qur'an, sadaqah is much less formally established than the sometimes similar practice of zakat, and in many cultures this takes a form closer to gift-giving and generosity among friends than charity in the strict sense, i.e. no attempt is made to give more to guests "in need", nor is it as a religious obligation as Islamic charity is often viewed.

Purple envelope

The tradition of ang pao has also been adopted by the local Indian Hindu populations of Singapore and Malaysia for Deepavali. They are known as Deepavali ang pow (in Malaysia), purple ang pow or simply ang pow (in Singapore).[9] Yellow coloured envelopes for Deepavali have also been available at times in the past.[10]

See also

Sources

- Chengan Sun, "Les enveloppes rouges : évolution et permanence des thèmes d'une image populaire chinoise" [Red envelopes : evolution and permanence of the themes of a chinese popular image], PhD, Paris, 2011.

- Chengan Sun, Les enveloppes rouges (Le Moulin de l'Etoile, 2011) ISBN 978-2-915428-37-7.

- Helen Wang, "Cultural Revolution Style Red Packets", Chinese Money Matters, 15 May 2018.

References

- ↑ http://www.fengshuiweb.co.uk/advice/angpow.htm

- ↑ Students and future students in the sciences are typically rewarded handsomely

- ↑ "How Social Cash Made WeChat The App For Everything". Fast Company. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ↑ Young, Doug. "Red envelope wars in China, Xiaomi eyes US". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Chun, Flora; Lee, Chun. "Silicon Valley Startup Reinvents an Ancient Tradition: The Red Envelope". Epoch Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ "Why this Chinese New Year will be a digital money fest". BBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Tencent, Alibaba Send Lunar New Year Revelers Money-Hunting - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ↑ Fox-Brewster, Thomas. "Inside Sony's Mysterious 'Red Pockets': Hackers Blow Open China Bribery Probe". Forbes. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ http://design-cu.jp/iasdr2013/papers/1893-1b.pdf

- ↑ http://chinesenewyearlanterns.blogspot.com.au/2013/12/uses-of-ang-pow-among-different-races.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red envelope. |