Railways in Northallerton

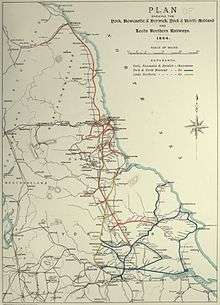

The network of Railways in Northallerton, North Yorkshire, England, was a result of three different companies building lines radiating from the town between 1841 and 1852. The companies were all amalgamated into the North Eastern Railway (NER) which was subsumed into the larger London and North Eastern Railway in 1923 and then British Rail in 1948. Closures by British Rail resulted in two of the lines, the Wensleydale line and the section of the Leeds Northern Railway to Harrogate, closing in 1954 and 1969 respectively. The former Wensleydale line was retained as a freight branch and resurrected as a heritage railway in 2003 whilst the line to Harrogate closed completely. Despite these closures and rationalisation, the station still acts as a major junction on the East Coast Main Line.

The current railway station in Northallerton is on the East Coast Main Line and on the Transpennine Express Northern Line. The station is 200 miles (320 km) north of London King's Cross, 30 miles (48 km) north of York railway station[1] and 175 miles (282 km) south of Edinburgh Waverley railway station.[2]

| Railways in Northallerton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

1841–1901

A railway between York and Darlington through Northallerton was first suggested in 1826 in the York Herald newspaper,[3] with the first railway arriving in Northallerton under the Great North of England Railway (GNE), which had followed the route proposed. The GNE had pushed their line up from York, which opened to mineral traffic in January 1841 and to passengers in March of the same year.[4] Whilst navvies were digging through the raised earth in the Castle Hills area of Northallerton, three Roman sarcophagi were unearthed which were then transported to Darlington.[5] Northallerton station was opened in March 1841, and the "York Herald" described is as being "in the Elizabethan Gothic style".[6] Although much remodelled, the present station is still in the same location, with staggered platforms as it was when first built.[7][8] Full opening beyond Darlington to Newcastle did not come until 1844. In 1842, the GNE was absorbed into the Newcastle & Darlington Junction Railway (N&DJR),[9] who, in 1846, had gained Parliamentary approval for a line between Northallerton and Bedale. Work started in the same year, but because of the immoral practices of George Hudson, who controlled the N&DJR, work was halted in early 1848,[10] though the line did open up between Northallerton and Bedale in March 1848.[11] Various other schemes progressed the line up through Wensleydale and the N&DJR became part of the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway (YN&BR). The Wensleydale Line left Northallerton westwards[12] and had two connections with the mainline between Northallerton and Darlington; one at Castle Hills South and the other at Castle Hills North. Initially, access was only from the north (IE from the Darlington direction) which meant that any trains originating in Northallerton had to reverse.[13] This was remedied in 1882 with the opening of a direct curve onto the Wensleydale line.[14]

The third line to reach Northallerton was the Leeds Northern Railway (LNR), previously the Leeds & Thirsk Railway, who opened up their line into Northallerton in June 1852.[15] The LNR line paralleled the YN&BR line but lower down and to the west. The GNE formation was built above the level of the land on an embankment that took it from what would be Cordio Junction to the area of Castle Hills on an embankment made up of 252,641 cubic yards (193,158 m3) of earth.[16] The earth had been displaced when the company had cut through and levelled the Castle Hills area to the north of the station site; this was the second hardest engineering task undertaken by the railway between York and Darlington after the stone viaduct was installed at Croft.[17] The LNR had their own station called Northallerton Town in the North Bridge area of the town.[18] The LNR passed under the YN&B just north of the station and a short tunnel was driven under the YN&B line at an angle of 23% to achieve this; it necessitated tunneling whilst still keeping the upper line open.[19][note 1][8][20] No work was undertaken on this for some time until designs and plan for the building of the tunnel were submitted to the YN&B engineers for approval from the LNR engineer, Joshua T Naylor.[21] The tunnel was constructed by driving piles into the GNE embankment and inserting a platform onto the piles and supporting the rails. Then it was dug out and the space immediately bricked up until the arches at either end could be completed.[22] The resultant tunnel is 26-foot (7.9 m) wide and 160-foot (49 m) long.[23]

.jpg)

A spur was built in 1856 at the north end of the present station to allow trains to and from Melmerby to call at the main station and still access the line towards Eaglescliffe and Stockton.[24] This route was taken via the Thirsk line from Melmerby and then north up what would become the ECML to Northallerton. This, along with the YN&B and the LNR becoming part of the North Eastern Railway in 1854,[note 2][25] precipitated the closure of Northallerton Town station (LNR) although it remained open for well over a century as a goods depot.[26] The line to Wensleydale also became absorbed into the NER in 1858.[27]

The LNR opened up two platforms on their line adjacent to Northallerton station.These remained in use after the mainline trains had been diverted through the station and via Thirsk.[28] The low platforms served as a terminal point for local trains from Melmerby (via Sinderby until 1901, when the line from Melmerby was doubled and became the key line north,[note 3][29] with the line from Thirsk to Melmerby becoming secondary. When the mainline trains were re-routed via the Melmerby to Northallerton line, the NER installed a junction at Cordio Wood to feed a spur into the south of the main station.[30][31] The low platforms became redundant after this and they were abandoned although resurrected during the Second World War and engineering diversions.[30] Access to the low platforms was via a path from the upper platforms. A door in the subway underneath the main running lines also allowed passengers to interconnect between all platforms.[32]

Other lines were planned, some actually gained Parliamentary approval. One was the York & Carlisle Railway which proposed a railway from Northallerton and from Bishop Auckland meeting near to Barnard Castle and driving across the Pennines. This plan was abandoned in 1846 when the company merged with another.[33]

1901–1948

In 1911, the station was remodelled again after an improved connection was installed on the western side of the line for access to the Wensleydale line. The down platform (Darlington-bound) was converted into an island platform with two running lines and a north-facing bay for the Wensleydale services. Another bay was installed on the up platform (York-bound) which allowed services to depart south for the Ripon line, although the stopping service on the line up until 1901 had used the low platforms adjacent to the main station.[8][28][34]

Starting in 1897, the tracks were "widened" in several sections between York and Northallerton.[35][36] In 1931, the London and North Eastern Railway quadrupled most of the track and created a grade separated junction south of Northallerton at a place designated Longlands Junction by 1933.[31][37] This connected with the original formation of the line from Ripon, and allowed freight to avoid the station from the York direction altogether. Trains heading south from the Middlesbrough direction would gain the route south by means of a short tunnel (Longlands Tunnel 55 yards (50 m)) underneath the fast lines routed through the station.[38] In 1942, the LNER installed up and down slow lines between Pilmoor and Thirsk as wartime necessities led to an upsurge in traffic.[39] British Rail completed the quadrupling of the whole route in 1959 and 1960.[40]

In 1941, concerns about wartime bombing prompted another chord to be built from just north of Romanby Road level crossing to Castle Hills Junction.[41] This would connect the lower lines with the upper lines and was opened in November 1941.[42] In case of Northallerton station being bombed, this would provide an alternative route for trains to use should the station area be put out of action. This new section was engineered with a rather unique feature; because of its gradient it was too low to bridge the Wensleydale line but additionally too high to dive under the railway.[41] The designers created two moveable sections on rail wheels which when pushed together, created a bridge section to allow trains bound to and from Wensleydale to traverse the section.[43] Should the wartime chord need to be used, the moveable bridge sections could be pushed out of the way onto specially created sidings on either side of the running lines.[44] The bridge was constructed from two 17-foot (5.2 m) girders that straddled the lower running lines.[42] The bridge completed the track circuits and thus prevented trains from running under when the bridge was in place, or from running over it if the lower wartime lines were in use. In this case, trains could still access the Wensleydale line by reversing at Castle Hills Junction. Apart from testing, there is no evidence that the wartime chord was used as Northallerton was rarely attacked (some bombs did land on one of the livestock marts).[45] Closure of this section came in 1946.[46]

1948–present day

When the passenger service was stopped on the Wensleydale line in April 1954 (due to its £14,000 per year loss-making revenue according to British Rail),[47][11][48] the direct curve from the station onto the line was used less and less until it closed in 1970.[31][49] Thereafter, freight services had to use Castle Hills siding and reverse into the loop to run-round. Some freight trains would traverse the line with a locomotive at both ends of the train, a procedure known as Top and Tail, which removed the necessity to have to reverse and run-round.[50] Services on the line comprised various loads, but up until December 1992,[11] it was used to convey limestone from Redmire to the British Steel complex at Redcar.[51] This operation involved the train arriving from Teesside into the station via the Eaglescliffe line, stopping, then reversing into the Castle Hills siding and then continuing up the branch. On returning, the train would reverse the process to access the Eaglescliffe line.[52] In 1996, the Ministry of Defence paid £750,000 to upgrade the line to convey military vehicles in and out of Catterick Camp.[53]

The last section of line to be closed in the area was the old Leeds Northern Line from Harrogate and Ripon which officially closed to passengers in 1967 but was not closed completely until 1969. The widened lines on the ECML, which provided four tracks between Northallerton and York, were seen as an easier route south than some of the steeply graded sections of railway around Ripon and Wetherby.[37] The former LNR route was re-opened to provide services in the aftermath of the Thirsk rail crash. Some questioned the validity of closing the route citing the train crash at Thirsk as reasons to keep it open as an alternative line when the ECML would be closed.[54] Various reports have detailed re-opening this line but some historical studies have suggested that the route should only open between Ripon south to Harrogate as there would be no business case to provide for a railway running further north.[55][56][57] In 2015, North Yorkshire County Council submitted their formal plans for many transport schemes in North Yorkshire, the provision of a railway connecting Harrogate and Ripon to the ECML was among them. However, whilst the routeing of the railway north suggests that the freight railway through Northallerton could be closed, the plan calls for the junction of a re-opened line to be north of Northallerton town.[58][59]

With the loss of the local and long distance traffic on the Wensleydale and Harrogate lines, the bay platforms at the southern and northern ends of the station were taken out of commission. In 1982, British Rail announced its intention to revamp the dilapidated station, but with no funding forthcoming from local authorities, the options to retain the Victorian buildings were limited.[60] The down side buildings were removed in 1972–1973 and the up side lost its glass canopies in 1985.[61] The station was completely remodelled between 1985 and 1986 with the down line on the western edge of the station (the down relief line) being removed too.[62][63]

Local passenger services were lost on the Northallerton–Eaglescliffe route and most other passenger workings were transferred away leaving just freight using the line. British Rail did start up a named train to Midldlesbrough, the Cleveland Executive, but this ceased just before the ECML was electrified due to poor patronage north of Northallerton station. The route regained passenger services again in the 1990s when Regional Railways introduced the Middlesbrough–Manchester Airport services which used the line rather than having to reverse at Darlington station.[64]

The ECML was fully electrified with a 25 kiloVolt Alternating Currency overhead catenary throughout in 1991.[65] Though the section between York and Northallerton was energised and tested in September 1990,[66] electric services between London King's Cross and Edinburgh did not commence until July 1991.[67] Electrification involved raising many bridges in the town and also spelt the end for the signalbox which had been opened in September 1939 and controlled a large section of the ECML.[68] The signalbox officially closed in April 1990 when control was transferred over to York IECC,[69] although the control of the barriers (but not the signals) at the Low Gates level crossing was kept under the authority of the box at Low Gates.[61] Signalling control now rests at the Rail Operating Centre at York.[20][70]

The North Eastern Railway had pursued a scheme to electrify the line between Northallerton and Ferryhill via Stockton in 1922/1923.[71] This route was also considered for electrification by British Rail for a proposed Channel Tunnel freight terminal on Teesside in 1994, but the idea was not taken past the planning stage.[72] In 2009, electrification was announced on the Transpennine route between Manchester Victoria, Huddersfield, Leeds and York. As bolt on to this, electrification of the line between Northallerton and Middlesbrough was mooted by Network Rail to provide through running between the Manchester area and Middlesbrough.[72]

In 2017, one of the platforms in Northallerton station was lengthened to enable the new Class 800 trains to call at the station on East Coast services.[73]

Wensleydale railway

In 2003, the Wensleydale Railway signed a 99-year lease with Railtrack (the predecessor of Network Rail) and started running services on the former Wensleydale line.[74] Initially, trains only ran to Leeming Bar as the eastern terminus, but this changed in 2014 when Northallerton West railway station was opened. The station is a temporary structure as the Wensleydale Railway were keen to reopen the closed 1970 curve and run trains into, or as close as they could get to, Northallerton Railway station. However, the north-facing bay platform that was used for the Wensleydale branch has been filled in and now forms part of the car park.[75] The section between Leeming Bar and Northallerton does not see scheduled services as the level crossing on Yafforth road is in need of an upgrade. In 2016, a service struck a car on the level crossing[76] and whilst the report did not attribute direct blame on the company, it did say that the approaches and sighting of the level crossing should be improved.[77][note 4][78]

Goods

The North Eastern Railway applied for Parliamentary permission to build a freight yard in-between the Darlington and Eaglescliffe lines. It was given permission in 1901 and 1903 but did not construct anything.[79] The town had two goods yards; one was in the present station and the other next to the closed Northallerton Town railway station. These were known as High and Low Goods Yard(s) respectively.[80] Northallerton station used to have an auction mart next to it and the cattle was forwarded from the that yard which also possessed coal drops. It remained a wagonload freight location up until the early 1980s.[81] The low yard was used for general merchandise.[82] Both yards have three and two sidings respectively which are still used but only for engineering purposes.

Northallerton only forwarded the same types of freight as any other station on the local lines. The only exception was the Wensleydale Pure Milk Society Dairy which was located just to the north west of the station. It forwarded milk products to London, Hull, Newcastle, Sunderland and Dewsbury, as well as receiving incoming milk especially from Wensleydale. The one odd wagon movement was a hand-pushed trolley, operated by two workers, which was pushed into the station from the creamery. This conveyed cream for dispatch and the wagon was specially converted so that it could work the line,[83] and had a red flag placed on a very tall pole so that its movement could be observed by traincrew.[84]

Current services

Northallerton station is served by LNER services between Edinburgh and London King's Cross, Transpennine Express (TPE) services between Middlesbrough and Manchester airport, Newcastle and Liverpool Lime Street and Grand Central services between Sunderland and London King's Cross. Most LNER services and all CrossCountry services pass through at speed without stopping. One TPE service per hour in each direction does not stop at the station either.

Most freight trains are routed via the old Leeds Northern Railway line on the lower tracks which avoids having to go through the two lines in the station. This means that freight trains travelling on the lower lines cross over four level crossings in the town. From south to north these are;[20]

- Boroughbridge Road Gates - this takes the A167 across the freight lines and under the fast lines.

- Romanby Road - leads the local road from Romanby into Northallerton

- Springwell Lane - a road across the freight lines to a small number of houses and provides foot access to Northallerton West railway station

- Low Gates - takes the A167 Darlington road across the Northallerton–Eaglescliffe Line. This level crossing is the busiest as all trains from the Middlesbrough area cross here.

Low Gates level crossing often has its barriers down at peak time for 25 minutes in an hour.[85] This leads to many traffic tailbacks on the A167 which can take over 15 minutes for the traffic to clear.[86] Problems with queuing traffic and the congestion it causes through the town have led to calls for the level crossing to be bypassed, bridged or closed altogether. One option suggested was that the corridor that the freight lines occupy be turned into an inner ring road and a new formation railway cut further north to provide a new chord to the Middlesbrough line from the ECML further north than the current station.[87][88] This would mean traffic could use the trackbed to access the A167 without going through the town as there is no bypass around the town for road traffic.[89]

Stations and engine shed

- Northallerton railway station; opened in 1841, completely remodelled in 1986 when the buildings on the up side of the line (York bound) were demolished.[90] The station is run by Transpennine Express, with other services being provided by LNER and Grand Central.[91] The last recorded use of the low platforms was in February 1961 after the station was damaged by a derailment (see incidents section). Trains were diverted via the low platforms and a diversion at Eaglescliffe to regain the main line at Darlington.[92]

- Northallerton Town railway station; opened in 1852 and closed in 1856[93]

- Northallerton West railway station; opened in 2014.[94] The platform at Northallerton West is a semi-permanent structure that sits on a passing loop. Only one platform is provided (on the south side of the line) and access is only on foot across Springwell Lane Level Crossing.[95]

A two road engine shed was provided at Northallerton for services on the Wensleydale branch. It was built in 1857 and replaced in 1881 with an extension added in 1886.[96] The shed was located adjacent to the low platforms at Northallerton station and had one through and one dead-end line.[97] The shed was coded as 51J under British Railways as a sub-shed of Darlington.[98] With the withdrawal of passenger services on the Wensleydale line, the justification for keeping the engine shed open was diminished. The shed closed in March 1963, nine years after passenger traffic had ceased on the branch. The site is now in private business use.[99]

The turntable in the town was located in the goods yard adjacent to the main station. It could accommodate locomotives up to a length of 42 feet (13 m).[100] Its location at the station rather than adjacent to the locomotive shed was a legacy owing to when the Leeds Northern services would terminate in the station and run-round before proceeding south again. An engine moving from the station to the locomotive shed would need to negotiate over 1 mile (1.6 km) and two junctions to get there.[80]

Incidents

- 1870 - A boiler explosion occurred in a steam locomotive in Northallerton station; whilst there was some injuries, no-one was killed.[101]

- July 1870 - The landlord of the Golden Lion Hotel in Northallerton was using the foot crossing in the station to access platform 2 when he stopped to look at his watch. He received fatal injuries from the crash. Mainly because of this accident (but also on account of other people sustaining injuries in the same location) a subway was opened up soon afterwards to replace the foot crossing.[102]

- 21 November 1889 - A driver who was due to be shown the road for the line between Northallerton and Hawes, jumped on board the guard's van of the train he was due to be learning on whilst it passed through the station. He fell back from the van onto the platform and his arm was badly smashed between the van and the platform. It was later amputated at Northallerton's Cottage Hospital.[103]

- 4 October 1894 - A Scotch Express heading south had experienced trouble with brakes so a pilot engine was attached at Darlington. The pilot loco (although at the front of the train) assumed that the other driver was looking out for the signals, whereas the other driver assumed that as the pilot loco was at the front, he was looking out for the signals. The train went through a signal at danger and collided with the rear end of a goods train just north of Northallerton.[104] A passenger was killed.

- 23 December 1894 - A gale which struck most of Northern England, stripped the panels from the station roof and ripped off other fittings. No injuries or deaths were recorded.[105]

- In November 1913, a locomotive from the Wensleydale line was signalled onto the main line at Castle Hills, but was not cleared to run further south by the Northallerton signal box. The locomotive was returning to the shed and so had to run through on the main line to get to the shed. The signallers forgot about the light engine and two different signallers both accepted an express from the north. The driver of the light engine was surprised to see the distant signals being raised, which would not be necessary for him as he was only just going past the station. On realising something was wrong, the driver looked behind and saw the express running towards him. He started his engine to try and get clear, but both he and his fireman baled out onto the platform as their engine passed through Northallerton station. The express mananged to come to a halt and the light engine was found a little south of Northallerton having run out of steam.[106]

- September 1935 - a northbound express coming off of the Harrogate Line going north, saw that an express was on the main line and headed for the station too. The express from Harrogate performed an emergency stop. It was later determined that the driver of the express on the main line had been mistaken by the green signals further down the line through Northallerton station.[107]

- February 1961 - a parcels train derailed in the station ripping up the track and demolished part of the island roof. The newspaper and parcels were shredded in the crash which created a "snowstorm" effect. Despite it happening in daytime and the station busy with passengers, the only injury was to the guard of the train who was sent home from hospital on the same day.[92]

- 28 August 1979 - an Intercity 125 unit from London King's Cross to Edinburgh derailed south of the station but remained upright. The cause was later attributed to low gearbox oil lubricant which caused the piston to fail and lock the leading wheels on the train in place. With the rear power car pushing the train, this caused the flanges on the locked wheels to deform and strike the points south of the station, which buckled the rail. This caused the whole train to derail but it stayed upright and only one person required hospitalising overnight.[108]

- 3 August 2016 - a train on the heritage Wensleydale Railway struck a car on a level crossing near to the village of Yafforth which lies just west of Northallerton. Three people suffered injuries; the car driver and two passengers on the train.[77]

Gallery

66733 and GC HST at Northallerton Low Gates

66733 and GC HST at Northallerton Low Gates Former island line at Northallerton station

Former island line at Northallerton station Longlands Tunnel

Longlands Tunnel Northallerton Tunnel

Northallerton Tunnel The former goods yard by Northallerton station

The former goods yard by Northallerton station

Notes

- ↑ Some writers refer to the tunnel as a '"long bridge". The Eastern Trackmaps diagrams refers to the formation as a tunnel.

- ↑ Initially, the North Eastern Railway was created by the YN&B, the LNR and the York and North Midland Railway, with the Malton & Driffield Railway being amalgamated quite soon afterwards.

- ↑ The doubling began in March 1899 and took two years.

- ↑ The level crossing at Yafforth was used to stage a crash under the banner "Operation Zebra Smash" in 1994. Railtrack set the crossing up with fake barriers and pushed a train onto the level crossing which smashed a Vauxhall Astra GTE.

References

- ↑ "Report on the Derailment that occurred on 28th August 1979 at Northallerton" (PDF). railwaysarchive.co.uk. Department of Transport. p. 1. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Spaven, David; Holland, Julian (2013). Mapping the railways : the journey of Britain's railways through maps from 1819 to the present day. Glasgow: Harper Collins. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-00-750649-1.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 162.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 95.

- ↑ Lloyd, Chris (30 June 2010). "'Flourishing garden' now a supermarket". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 31 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Riordan 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Chrystal, Paul; Sunderland, Mark (2010). Northallerton through time. Stroud: Amberley. p. 45. ISBN 9781848681811.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1993, p. 71.

- ↑ Haigh Joy 1979, p. 16.

- ↑ Joy, David (2005). Guide to the Wensleydale Railway. Ilkley: Great Northern Books. p. 3. ISBN 1-905080-02-6.

- 1 2 3 Lloyd, Chris (17 February 2011). "LookingBack - Rails in the Dales". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 31 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Suggitt 2007, p. 54.

- ↑ Davies 1991, p. 197.

- ↑ Hoole 1985, p. 8.

- ↑ Burgess, Neil (2011). The lost railways of Yorkshire's North Riding. Catrine: Stenlake. p. 18. ISBN 9781840335552.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 349.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 141.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 143.

- ↑ Ingledew 1858, pp. 339–340.

- 1 2 3 Bridge, Mike (2016). Railway Track Diagrams; Eastern. Frome: Trackmaps. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9549866-8-1.

- ↑ Ingledew 1858, p. 340.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 513.

- ↑ Ingledew 1858, p. 341.

- ↑ Suggitt 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Langham, Rob (2013). "Introduction". The North Eastern railway in the First World War. Oxford: Fonthill. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-78155-081-6.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 329.

- ↑ Body 1989, p. 144.

- 1 2 "Disused Stations: Northallerton Low Level Station". www.disused-stations.org.uk. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "District News - Northallerton". The York Herald (14, 913). 25 March 1899. p. 11. OCLC 877360086.

- 1 2 Hoole 1977, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Cobb, M H (2003). The railways of Great Britain : a historical atlas at a scale of 1 inch to 1 mile vol. 2 (2 ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing. p. 436. ISBN 0-7110-3003-0.

- ↑ Jenkins 1993, p. 72.

- ↑ Hoole 1985, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Goode, C.T. (1980). The Wensleydale branch. Trowbridge: Oakwood Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-85361-265-X.

- ↑ Hoole 1977, p. 51.

- ↑ Haigh Joy 1979, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 Haigh Joy 1979, p. 17.

- ↑ Body 1989, p. 137.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 98.

- ↑ Hoole 1977, p. 54.

- 1 2 Chapman 2010, p. 8.

- 1 2 Jenkins 1993, p. 65.

- ↑ Body 1989, p. 136.

- ↑ Davies 1991, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Berry, Chris (26 November 2012). "Market's century at heart of town". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ↑ Davies 1991, p. 199.

- ↑ "Return to tender: Rail trip back in time". The Yorkshire Post. 26 April 2004. Retrieved 31 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 338.

- ↑ Railways of the Yorkshire Dales. Ilkley: Great Northern Books. 2005. p. 61. ISBN 1-905080-03-4.

- ↑ Shannon, Paul (2009). Diesel decades 1990s (1 ed.). Hersham: Ian Allan. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7110-3384-9.

- ↑ Shannon, Paul (2008). Rail freight since 1968 : bulk freight. Great Addington, Kettering: Silver Link. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85794-299-6.

- ↑ Goodyear, Alan (December 1989). "Rails to Redmire". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 135 no. 1, 064. Cheam: Prospect Magazines. pp. 792&ndash, 794. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin (11 April 1996). "Army rolls up to save rail link". The Guardian. p. 5. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ↑ Young, Alan (2015). The Lost Stations of Yorkshire; The North and East Ridings. Kettering: Silver Link. pp. 44&ndash, 46. ISBN 978-1-85794-453-2.

- ↑ Chapman, Hannah (12 May 2004). "Railway renewal plan is backed". The Northern Echo. p. 4. ISSN 2043-0442.

- ↑ "Untitled Page". www.forgottenrelics.co.uk. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "Reopening of 11-mile Harrogate-Ripon rail link takes a step nearer". Yorkshire Evening Post. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "A Strategic Transport Prospectus for North Yorkshire" (PDF). northyorks.gov.uk. p. 35. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Windham, Dan (29 October 2015). "County Council include reopening of Ripon railway in transport plans". The Ripon Gazette. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 396.

- 1 2 Jenkins 1993, p. 181.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 339.

- ↑ Jenkins 1993, p. 186.

- ↑ Semmens, P W B (August 1994). "Class 158s spread their wings". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 140 no. 1, 120. London: IPC. p. 26. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ↑ Body 1989, p. 207.

- ↑ "Electrification of the East Coast Main Line; progress report No. 14" (PDF). railwaysarchive.co.uk. British Rail. May 1992. p. 54. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Bickerdyke, Paul, ed. (August 2018). "Time Traveller". Rail Express. No. 267. Horncastle: Mortons Media. p. 35. ISSN 1362-234X.

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, pp. 396–397.

- ↑ Rhodes, Michael (2015). Resignalling Britain. Horncastle: Mortons Media Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-909128-64-4.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 97.

- 1 2 Merrick, Robert (15 August 2012). "Plan to electrify railway revived". The Northern Echo. p. 15. ISSN 2043-0442.

- ↑ Prest, Victoria (29 August 2017). "Rail works ready for new Azuma trains". York Press. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Robinson, Stephen (30 June 2003). "The railway that came back from the dead Train breathes new life into a Yorkshire dale". The Telegraph. p. 9. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ↑ Robinson, Stephen (29 June 2003). "The railway that came back from the dead". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ "Woman airlifted to hospital after crash with North Yorkshire train at level crossing". The Yorkshire Post. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Collision at Yafforth level crossing, 3 August 2016". gov.uk. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Marsden, Colin (November 1994). "Operation Zebra Smash". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 140 no. 1, 123. London: IPC. p. 11. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 106.

- 1 2 Davies 1991, p. 198.

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 31.

- ↑ Davies 1991, p. 202.

- ↑ Hoole 1985, p. 11.

- ↑ Blakemore, Michael (2005). Railways of the Yorkshire Dales. Ilkley: Great Northern Books. p. 4. ISBN 1-905080-03-4.

- ↑ Chapman, Hannah (2 June 2016). "How can Northallerton's level crossing congestion woe be solved?". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Foster, Mark (2 February 2000). "Town fears railway plans will increase traffic jams". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 31 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Mackintosh, Stuart (19 September 2001). "Railway line diversion plan is backed by council chiefs". The Northern Echo. p. 6. ISSN 2043-0442.

- ↑ Foster, Mark (22 July 2016). "Battle to beat jams in traffic-choked town". York Press. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Barnard, Ashley (20 September 2016). "Radical solutions to Northallerton's traffic misery are unveiled". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 31 July 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Chapman, Vera (2005). Around Northallerton. Stroud: History Press. p. 94. ISBN 9781845881764.

- ↑ Willis, Hoe (8 October 2004). "Unhappy passengers ready to set up rail action group". The Northern Echo. p. 6. ISSN 2043-0442.

- 1 2 "Northallerton Rail Crash". Evening Gazette. 16 February 1961. p. 1. ISSN 0964-3095.

- ↑ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The directory of railway stations : details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present. Sparkford: Stephens. p. 172. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ↑ Willis, Joe (31 October 2014). "Works starts on new rail platform to link Northallerton to Dales". Darlington and Stockton Times. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Getting Here - Wensleydale Railway". wensleydalerail.com. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Jenkins 1993, p. 51.

- ↑ Jenkins 1993, p. 74.

- ↑ Bolger, Paul (1984). BR Steam Motive Power Depots; NER. Surrey: Ian Allan. p. 54. ISBN 0-7110-1362-4.

- ↑ Thompson & Groundwater 1992, p. 71.

- ↑ Davies 1991, p. 200.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 99.

- ↑ Riordan 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ "Shocking accident at railway station". The York Herald (12, 006). 23 November 1889. p. 3. Retrieved 7 August 2018. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ "The Disastrous Gale". The York Herald (13, 590). 24 December 1894. pp. 5&ndash, 6. OCLC 877360086.

- ↑ "Race With Death" (PDF). railways archive.co.uk. Adelaide Advertiser. 24 December 1913. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Welbourn, Nigel (1997). Lost Lines North Eastern. Shepperton: Ian Allan. p. 40. ISBN 0-7110-2522-3.

- ↑ "Report on the Derailment that occurred on 28th August 1979 at Northallerton" (PDF). railwaysarchive.co.uk. Department of Transport. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

Sources

- Body, Geoffrey (1989). Railways of the North Eastern Region; Vol 2, Northern Operating Area. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 1-85260-072-1.

- Chapman, Stephen (2010). Railway Memories No. 23; Northallerton, Ripon & Wensleydale. Todmorden: Bellcode Books. ISBN 978-1-871233-23-0.

- Davies, Chris (September 1991). "Northallerton". Backtrack. Vol. 5 no. 5. Penryn, Cornwall: Atlantic. ISSN 0955-5382.

- Haigh, Alan; Joy, David (1979). Yorkshire Railways. Clapham: Dalesman Books. ISBN 0-85206-553-1.

- Hoole, Ken (1977). Railways in the Yorkshire. Clapham: Dalesman Books. ISBN 0-85206-418-7.

- Hoole, Ken (1985). Railways in the Yorkshire Dales. Clapham: Dalesman Books. ISBN 0-85206-826-3.

- Hoole, Ken (1974). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain; Volume 4 The North East. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-6439-1.

- Ingledew, C J Davison (1858). History and Antiquities in the County of York. London: Bell & Daldy. OCLC 557309753.

- Jenkins, Stanley (1993). The Wensleydale Branch; a New History. Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-437-7.

- Riordan, Michael (1996). Britain in old photographs; Northallerton. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-0839-4.

- Riordan, Michael (2002). The History of Northallerton, North Yorkshire, from Earliest Times to the Year 2000. Pickering: Blackthorn Press. ISBN 0-9540535-0-8.

- Suggitt, Gordon (2007). Lost Railways of North & East Yorkshire. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-918-5.

- Thompson, Alan; Groundwater, Ken (1992). British Railways Past and Present No. 14: Cleveland and North Yorkshire Part 2. Northamptonshire: Silver Link. ISBN 0-947971-84-X.

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1915). The North Eastern Railway, its rise and development. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: A Reid & Co. OCLC 854595777.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Railways in Northallerton. |