Protostome

| Protostomes | |

|---|---|

| |

| A centipede (Ecdysozoa) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia Grobben, 1908 |

| Superphyla | |

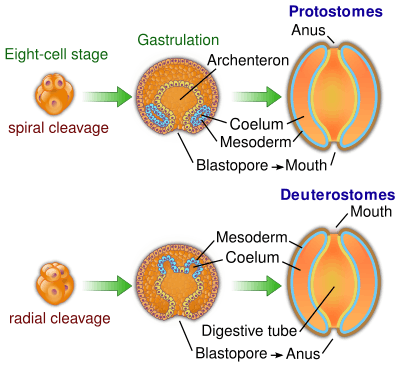

Protostomia (from Greek πρωτο- proto- "first" and στόμα stoma "mouth") is a clade of animals. Together with the deuterostomes and xenacoelomorpha, its members make up the Bilateria, mostly comprising animals with bilateral symmetry and three germ layers.[1] The major distinctions between deuterostomes and protostomes are found in embryonic development and is based on the embryological origins of the mouth and anus.

In most, but not all[2][3] protostomes, the mouth forms first, then the anus, whereas the reverse is true in deuterostomes.

Protostomy

In animals at least as complex as earthworms, the embryo forms a dent on one side, the blastopore, which deepens to become the archenteron, the first phase in the growth of the gut. In deuterostomes, the original dent becomes the anus while the gut eventually tunnels through to make another opening, which forms the mouth. The protostomes were so named because it was once believed that in all cases the embryological dent formed the mouth while the anus was formed later, at the opening made by the other end of the gut. It is now known that the fate of the blastopore in protostomes is extremely variable. While the evolutionary distinction between deuterostomes and protostomes remains valid, the descriptive accuracy of the name 'protostome' (in Greek: "first-mouth") is disputable.[2]

Protostomes and deuterostomes differ in several ways. Early in development, deuterostome embryos undergo radial cleavage during cell division, while many protostomes (the Spiralia) undergo spiral cleavage.[4] Animals from both groups possess a complete digestive tract, but in protostomes the first opening of the embryonic gut develops into the mouth, and the anus forms secondarily. In deuterostomes, the anus forms first while the mouth develops secondarily.[5][2] Most protostomes have schizocoelous development, where cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm. In deuterostomes, the mesoderm forms by enterocoelic pouching, through invagination of the endoderm.[6]

Evolution

The common ancestor of protostomes and deuterostomes was evidently a worm-like aquatic animal. The two clades diverged about 600 million years ago. Protostomes evolved into over a million species alive today, compared to about 60,000 deuterostome species.[7]

Protostomes are divided into the Ecdysozoa, e.g. arthropods, nematodes; the Spiralia, e.g. molluscs, annelids, platyhelminths, and rotifers. A modern (2011) consensus phylogenetic tree for the protostomes is shown below.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][11] It is indicated when approximately clades radiated into newer clades in millions of years ago (Mya).[15]

| Bilateria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

| Wikispecies has information related to Protostomia |

- ↑ Hejnol, A., Obst, M., Stamatakis, A., Ott, M., Rouse, G. W., Edgecombe, G. D., et al. (2009). Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B, 276, 4261–4270.

- 1 2 3 A. Hejnol M. Q. Martindale. "The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore - open questions about questionable openings". In M. J. Telford; D. T. J. Littlewood. Animal Evolution — Genomes, Fossils, and Trees. pp. 33–40.

- ↑ Martín-Durán, José M.; Passamaneck, Yale J.; Martindale, Mark Q.; Hejnol, Andreas (2016). "The developmental basis for the recurrent evolution of deuterostomy and protostomy". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1: 0005. doi:10.1038/s41559-016-0005.

- ↑ Valentine, James W. (July 1997). "Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life". PNAS. The National Academy of Sciences. 94 (15): 8001–8005. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8001V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001. PMC 21545. PMID 9223303.

- ↑ Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael (2005). The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 717. ISBN 978-0-521-83762-0.

- ↑ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. The ancestor’s tale. Boston. Mariner Books. 2004. p. 377–386

- ↑ Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Giribet, Gonzalo; Dunn, Casey W.; Hejnol, Andreas; Kristensen, Reinhardt M.; Neves, Ricardo C.; Rouse, Greg W.; Worsaae, Katrine; Sørensen, Martin V. (June 2011). "Higher-level metazoan relationships: recent progress and remaining questions". Organisms, Diversity & Evolution. 11 (2): 151–172. doi:10.1007/s13127-011-0044-4.

- ↑ Fröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter (2017-04-04). "Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans". Nature Communications. 8 (1). Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....9F. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w.

- ↑ Smith, Martin R.; Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2014). "Hallucigenia's onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda". Nature. 514 (7522): 363–366. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..363S. doi:10.1038/nature13576.

- 1 2 "Palaeos Metazoa: Ecdysozoa". palaeos.com. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- ↑ Yamasaki, Hiroshi; Fujimoto, Shinta; Miyazaki, Katsumi (June 2015). "Phylogenetic position of Loricifera inferred from nearly complete 18S and 28S rRNA gene sequences". Zoological Letters. 1: 18. doi:10.1186/s40851-015-0017-0.

- ↑ Nielsen, C. (2002). Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850682-1.

- ↑ "Bilateria". Tree of Life Web Project. 2001. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide (2008-04-27). "The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1496): 1435–1443. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233. PMC 2614224. PMID 18192191.

.jpg)