Prime Minister of the Philippines

| Prime Minister of the Philippines Punong Ministro ng Pilipinas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Style | The Honourable |

| Appointer | Batasang Pambansa on the nomination of the President of the Philippines |

| Precursor |

Office established (pre-1899) President of the Philippines (1978) |

| Formation |

January 2, 1899 (1st creation) June 12, 1978 (2nd creation) |

| First holder | Apolinario Mabini y Maranan |

| Final holder | Salvador H. Laurel |

| Abolished |

November 13, 1899 (1st abolition) March 25, 1986 (2nd abolition) |

| Succession | President of the Philippines (1899–1978; 1986) |

The Prime Minister of the Philippines (Filipino: Punong Ministro ng Pilipinas) was the official designation of the head of the government and of the Cabinet, whereas the President of the Philippines was the head of state and chief executive of the Philippines from 1978 until the People Power Revolution in 1986. A limited version of this office existed temporarily in 1899 during the First Philippine Republic.

History

First creation (1899)

The 1899 Constitution of the Philippines created the office of the Council of Government (Spanish: Consejo de Gobierno) which was composed of the President of the Council (Spanish: Presidente del Consejo de Gobierno) and seven secretaries.[1] The president of the revolutionary government led by Emilio Aguinaldo, appointed his advisor Apolinario Mabini as the first President of the Council of Government through a decree issued January 2, 1899.[2] Mabini also became the finance minister of the Republic. The President of the Council was also equivalent to a prime minister as he headed up the secretaries, or ministers that advised the President of the Republic.[3]

On December 10, 1898, on the other hand, the war between United States and Spain was concluded with Spain giving up all rights to Cuba and surrendering the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States.[4] Two days later, Aguinaldo ordered his lawyer Felipe Agoncillo to contest the Philippine status as an independent nation and no longer a Spanish colony since the declaration of independence on June 12, 1898.[5] However, the United States did not recognize Philippine sovereignty and announced their interest to annex the country by January 1899. This brought into serious foreign conflict when the Republic was formally established in January 23 at Malolos. By January 30, Aguinaldo resent Agoncillo, this time to the United States Senate, so as to reconsider their plans to annex the country and instead formally recognize Filipino independence.[6]

In the next few months, Mabini was pressured by political problems such as negotiating to end the hostilities between Filipinos and American forces left in the Philippines after the war. With the failure of having successful agreements with the US army to secure ceasefire, the first shot of the Philippine–American War erupted in February 4, 1899.[7] The revolutionary government was forced to vacate Malolos and transfer the seat of administration from place to place. Mabini, who was pressured then from his political adversaries and failure to stop the increasing guerilla insurgency during the war, left the post and surrendered to United States on May 7, 1899.[8]

One of the political adversaries who forced Mabini to leave office was Pedro A. Paterno, president of the Congress of the Republic since September 15, 1898. He opposed Mabini's offensive plan to counter United States attacks during the war, so he proposed peace plans with the Americans to Aguinaldo, such that the Philippines would be a protectorate of the United States with full autonomy. This was opposed by Mabini, however, Paterno and his allies convinced Aguinaldo to dissolve the Mabini cabinet which made the latter surrender to US.

The next day, May 8, Aguinaldo appointed Paterno as the President of the Council of Government.[9] One of his first moves during his term was to draft a copy of "Autonomy Plan" to the Schurman Commission which asks for peace settlement with the US government. This also states that the Filipinos are ready to drop the idea of independence and accept US sovereignty over the archipelago.[10]

Meanwhile, the takeover of Paterno of the revolutionary government and his actions towards the Schurman Commission infuriated General Antonio Luna, the commanding officer of the Philippine Army. He ordered to arrest Paterno and other members of the Cabinet, however, he was unsuccessful to send Paterno to jail.[10] Due to his actions, Paterno was forced to write a manifesto on June 2, 1899, stating a formal declaration of war against the United States.[11][12] On June 5, Luna was assassinated in Nueva Ecija, one of the alleged reasons for his murder was due to this conflict with Paterno.[13]

During the war, the seat of Aguinaldo changed from place to place northwards as the Americans grew aggressive. On November 13, 1899, Paterno was captured by US forces in Benguet, thus ending his term as the President of the Council.[9] Aguinaldo, however, did not appoint a successor for Paterno as he was busy for fleeing the Republic. On June 21, 1900, Paterno, as prisoner of war, accepted amnesty granted by the military governor General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. and he finally swore allegiance to the United States together with other members of Aguinaldo government.[14]

From 1899 to 1901, Philippines was headed by American military governors. When Aguinaldo was captured by Gen. Frederick Funston on March 23, 1901 at Palanan, Isabela, the country was headed then by civil governors until the formal establishment of self-autonomous Commonwealth on November 15, 1935. The 1935 Constitution that describes the operation of the Commonwealth does not have the provision of reviving the office of the President of the Council of the Government or creating any related position. This was continued until the Third Republic.

Second creation (1978–1986)

In 1976, President Ferdinand Marcos issued Presidential Decrees 991 and 1033 calling for a constitutional referendum, set on October 16, 1976. The voters were asked whether they wanted to lift the ongoing martial law since 1972; the majority approved its continuation. In addition, drafted and ratified was the Sixth Amendment to the 1973 Constitution, which fused legislative and executive powers in the office of President. One of its provisions at the time of ratification was that the President shall obtain the title of Prime Minister, thus re-creating the office after 1899.[15] Marcos, who concurrently as President, continued to wield the powers vested in the President by the 1935 Constitution. The Amendment also created the unicameral legislature known as the Interim Batasang Pambansa (Interim National Assembly or IBP), as well as a provision such that the President/Prime Minister will exercise legislative powers until martial law is lifted.[15][16]

On April 7, 1978, the first election for the Batasang Pambansa, was held since the abolition of the bicameral Congress under the 1973 Constitution. 150 out of 165 elected positions of the parliament were dominated by Marcos' ruling party, the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (New Society Movement).[17] By June 12, the IBP was inaugurated which also confirmed Marcos' position as the Prime Minister of the Philippines.[16]

Upon his inauguration for a third presidential term on June 30, 1981, Marcos formally relinquished his powers as Prime Minister. He appointed then-Finance Minister Cesar Virata to succeed him to the post during the opening of the fourth regular session of the IBP on July 27, 1981. Virata, a grand-nephew of former President Emilio Aguinaldo,[18] previously represented the country to World Bank's Council of Governors.[19] Until the 1986 People Power Revolution, Virata held this position. It was conjectured that Marcos bestowed his Prime Ministerial post to Virata because of the latter's distance from mainstream politics. Other than being Marcos' finance minister, Virata was not a political threat.[20]

Abolition

Upon her accession in late February 1986, Corazon Aquino appointed her Vice President and running mate Salvador Laurel to succeed Virata under her revolutionary government.[21] However, the premiership was later abolished in March 1986 with the release of Proclamation № 3, or the "Freedom Constitution".[22]

The subsequent and currently-enforced 1987 Constitution has no provisions for such a position, as the President is now both head of government and head of state.

Powers and duties

The office of the President of the Council of Government was created by 1899 Constitution of the Philippines on Title IX, with the role as the head of secretaries to the President of the Republic.[1] The first President of the Council was Apolinario Mabini, who also happened to be the concurrent Minister of Foreign Affairs. The President of the Council is equivalent to present-day Prime Minister, having the management of the day-to-day operations of the government.

The 1973 Constitution provided clear powers and duties of the Prime Minister starting at the administration of Ferdinand E. Marcos. Article IX, section 3 of the 1973 Constitution describes the primary qualification of an individual to become the Prime Minister: he must be a member of the Interim Batasang Pambansa (National Assembly).[23] To become a member of the Interim Batasang Pambansa, one must be a qualified citizen of the Republic and was elected by the popular district in which he will represent at the assembly.[24] Though the appointment of the Prime Minister is exactly written on the Constitution, however, the Prime Minister is exempted from impeachment,[25] thus paving way for whoever the Prime Minister will be, for an indefinite term.[26] On the same hand, the Prime Minister and his deputy may leave office at their own will.[27]

Apart being the head of government, the Prime Minister also presides over his Cabinet. He has the power to appoint Cabinet members, often from the National Assembly. Likewise, he also has the prerogative to remove them at his discretion.

He also has the following powers and duties:

- Appoint the Deputy Prime Minister that will have powers vested by the Prime Minister;[28]

- Present the program and state of the government to the National Assembly at the start of each regular session;[29]

- Control all ministries provided by the law;[30]

- Head the Armed Forces of the Philippines as their commander-in-chief;[31]

- Appoint the heads of government bureaus and offices, and promote brigadier-generals and commodores of the Armed Forces;[31]

- Grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons; remit fines and forfeitures after final conviction; and grant amnesties with the permission of the National Assembly, except at the time of impeachment;[32] and

- Guarantee foreign and local loans of the Republic.[33]

In Section 16, it was also mentioned that all powers previously vested by the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines to the President of the Republic shall be transferred to the Prime Minister unless the National Assembly provides those.[34] This includes the power of the Prime Minister to sign and create treaties and foreign agreements as well as appointment of ambassadors and consuls with the permission of the Commission on Appointments.[35]

Thus, the Prime Minister had full executive powers while the President was renegated in playing ceremonial functions only as head of state.

But, in 1981, the 1973 Constitution was amended to usher in a Peruvian-style semi-presidential form of government or in Marcos' words as "modified parliamentary system of government", in which full executive powers was restored to the President elected directly by the people, thus he was chief executive also. The President would be the one who will solely formulate the guidelines of national policy and had control of all ministries, had the power to contract loans, promulgates laws, the top maker of foreign policy, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces and the one who controls the national budget, as well as would be the one to appoint senior national government officials and promulgate the laws. He had still the power to issue presidential decrees that has the force of law even if the then unicameral parliament, the Batasang Pambansa was in session and creating laws under the Amendment No. 6 to the said Constitution in 1976.

The position of Prime Minister was retained. But, he was made as head only of the Cabinet as the President was both the head of state and government. He would be nominated by the President from among the members of the Batasang Pambansa, then the country's unicameral parliamentary legislature, in order to get elected by majority of its members thereof. He was also the Chairman of the Executive Committee, a collegial body, consisting of himself and of fourteen other persons that would assist the President in performing his duties and powers and would succeed him in case of death, resignation, impeachment or permanent incapacity until a new President is elected.

The Prime Minister, as assisted by the Cabinet would implement the guidelines of national policy as set forth by the President and he, together with the Cabinet was responsible also for a program of government, as approved first by the President, before the Batasang Pambansa.

He have also supervision of all ministries and under Executive Order No. 708 issued on July 27, 1981, he was tasked with supervising the day-to-day operations and details of administration of the government while the President would principally concentrate on major policy and decision-making processes.

The Prime Minister was also empowered to advise the President to dissolve the Batasang Pambansa in case of the issue of confidence on fundamental issues, but not of his personal integrity.

And, he was also tasked to submit to the Batasang Pambansa the bill of general appropriations of the national government for its consideration and enactment.

Together with the Cabinet, he was required to answer questions by the members of the Batasang Pambansa during the Question Hour about the general conduct of the government.

Lastly, he was authorized to act on official matters as delegated to him by the President, also under Executive Order No. 708.

So, in short, the post of the Prime Minister under the 1981 amendments to the 1973 Constitution was simply the chief assistant of the President in running the daily affairs of the Philippines.

List of Prime Ministers

| # | Name (Birth–Death) |

Party | Took office | Left office | President | Legislature | Era | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apolinario Mabini (1864–1903) |

|

Non-partisan | January 2, 1899 | January 23, 1899 | Emilio Aguinaldo | Malolos Congress | Revolutionary Government | |

| January 23, 1899 | May 7, 1899 | First Republic | |||||||

| 2 | Pedro A. Paterno (1857–1911) |

|

May 8, 1899 | November 13, 1899 | |||||

| Office abolished [n 1] November 14, 1899—June 12, 1978 | |||||||||

| 3 | Ferdinand E. Marcos (1917-1989) |

|

KBL | June 12, 1978[n 2] | June 30, 1981 | Ferdinand E. Marcos | Interim Batasang Pambansa | Martial law | |

| 4 | Cesar E. A. Virata (1930– ) |

|

July 28, 1981 | July 23, 1984 | Fourth Republic | ||||

| July 23, 1984 | February 25, 1986 | Regular Batasang Pambansa | |||||||

| 5 | Salvador H. Laurel (1928–2004) |

UNIDO | February 25, 1986 | March 25, 1986 | Corazon C. Aquino | ||||

| Defunct The presidential system is used; the President is head of both state and government by virtue of the 1987 Constitution | |||||||||

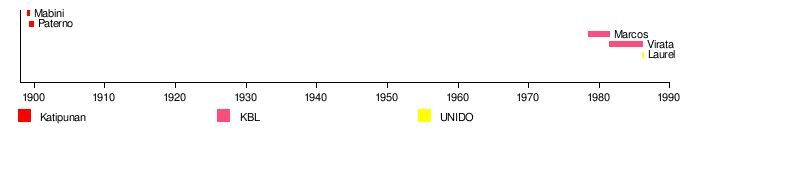

Timeline

Statistics

- Living former Prime Ministers:

- Cesar E. A. Virata (1981-1986) (born December 12, 1930) — 87 years, 304 days

- List of Prime Ministers by age at the start of term:

- Ferdinand E. Marcos — 60 years, 274 days

- Salvador H. Laurel — 57 years, 99 days

- Cesar E. A. Virata — 50 years, 200 days

- Pedro A. Paterno — 41 years, 69 days

- Apolinario Mabini — 34 years, 163 days

- List of Prime Ministers by tenure of office:

- Cesar E. A. Virata (1981-1986) — 4 years, 240 days

- Ferdinand E. Marcos (1978-1981) — 3 years, 18 days

- Apolinario Mabini (1899) — 184 days

- Pedro A. Paterno (1899) — 131 days

- Salvador H. Laurel (1986) — 28 days

See also

Notes

- ↑ The newly formed Philippines led by President Emilio Aguinaldo was ceded by Spain to United States as an aftermath of the Spanish–American War and a provision to the 1898 Treaty of Paris. From 1898–1901, the Philippines was headed by an American military governor, followed by American civil governors until 1935, when the Commonwealth of the Philippines was inaugurated. Since the establishment of the Commonwealth (1936–1946), Third Republic (1946–1969) until 1978, there is no Prime Minister post.

- ↑ Ferdinand Marcos became the first Prime Minister in 1976 when the Sixth Amendment was ratified. However, his claim to the post was verified after his party won majority of the National Assembly seats and declared him as Prime Minister on June 12, 1978.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Title IX, Article 73. 1899 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 81

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 82

- ↑ "Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain; December 10, 1898". Yale. 2009. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. Appendix G-1

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 236

- ↑ Tucker 2009, p. 352

- ↑ Keat 2004, p. 804

- 1 2 Tucker 2009, p. 466

- 1 2 Mojares 2006, p. 25

- ↑ Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200

- ↑ Mojares 2006, p. 26

- ↑ Tucker 2009, p. 346

- ↑ Mojares 2006, p. 31

- 1 2 Celoza 1997, p. 60

- 1 2 Taylor & Francis 2004, p. 3408

- ↑ Teehanke 2006, p. 160

- ↑ "Progressive Leader of the Philippines, Cesar Virata WG 1953". The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Case 2002, p. 217

- ↑ Celoza 1997, p. 75

- ↑ Steinberg 2000, p. 153

- ↑ "Philippines: Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Article IX, Section 3. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article VII, Section 2. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article XIII, Section 2. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Pomeroy 1992, p. 263

- ↑ Article IX, Section 9. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 5. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 10. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 11. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- 1 2 Article IX, Section 12. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 14. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 15. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article IX, Section 16. 1973 Constitution of the Philippines

- ↑ Article VII, Section 10. 1935 Constitution of the Philippines

Bibliography

Government documents

- 1899 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines

- 1935 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines

- 1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines

Published works

- Case, William (2002), Politics in Southeast Asia: Democracy or Less, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1636-X ISBN 978-0-7007-1636-4

- Celoza, Albert F. (1997), Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: the Political Economy of Authoritarianism, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-94137-X ISBN 978-0-275-94137-6

- Guevara, Sulpicio (1972), The Laws of the First Philippine Republic (The Laws of Malolos), 1898-1899, Manila: National Historical Commission Digitally archived and reproduced at the University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States since 2005.

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "Appendix C. Aguinaldo's Proclamation of June 23, 1898, Establishing the Revolutionary Government", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, retrieved 2011-04-15

- Keat, Gin Ooi (2004), Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-770-5 ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2

- Pomeroy, William J. (1992), The Philippines: Colonialism, Collaboration, and Resistance, International Publishers Co., ISBN 0-7178-0692-8 ISBN 978-0-7178-0692-8

- Steinberg, David Joel (2000), The Philippines: A Singular and A Plural Place, Basic Books, ISBN 0-8133-3755-0 ISBN 978-0-8133-3755-5

- Taylor & Francis (2004), Europa World Year Book 2, Book 2, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 1-85743-255-X ISBN 978-1-85743-255-8

- Teehankee, Julio (2006), Electoral Politics in the Philippines (PDF)

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009), The Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-951-4 ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1

| Preceded by Governor-General of the Spanish East Indies |

Head of government of the Philippines 1899 |

Succeeded by President of the Philippines |

| Preceded by President of the Philippines |

Head of government of the Philippines 1978–1986 |

President of the Philippines |