Toxin-antitoxin system

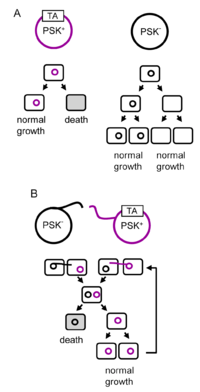

A toxin-antitoxin system is a set of two or more closely linked genes that together encode both a protein 'poison' and a corresponding 'antidote'. When these systems are contained on plasmids – transferable genetic elements – they ensure that only the daughter cells that inherit the plasmid survive after cell division. If the plasmid is absent in a daughter cell, the unstable antitoxin is degraded and the stable toxic protein kills the new cell; this is known as 'post-segregational killing' (PSK).[2][3] Toxin-antitoxin systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes, and organisms often have them in multiple copies.[4][5]

Toxin-antitoxin systems are typically classified according to how the antitoxin neutralises the toxin. In a Type I toxin-antitoxin system, the translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) that encodes the toxin is inhibited by the binding of a small non-coding RNA antitoxin to the mRNA. The protein toxin in a type II system is inhibited post-translationally by the binding of another protein antitoxin. Type III toxin-antitoxin systems consist of a small RNA that binds directly to the toxin protein.[6] There are also types IV-VI, which are less common.[7] Toxin-antitoxin genes are often transferred through horizontal gene transfer[8][9] and are associated with pathogenic bacteria, having been found on plasmids conferring antibiotic resistance and virulence.[1]

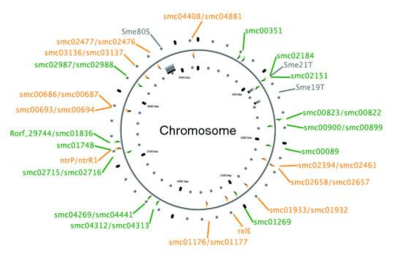

Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems also exist, some of which perform cell functions such as responding to stresses, causing cell cycle arrest and bringing about programmed cell death.[1][10] In evolutionary terms, toxin-antitoxin systems can be considered selfish DNA in that the purpose of the systems are to replicate, regardless of whether they benefit the host organism or not. Some have proposed adaptive theories to explain the evolution of toxin-antitoxin systems; for example, chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems could have evolved to prevent the inheritance of large deletions of the host genome.[11] Toxin-antitoxin systems have several biotechnological applications, such as a method of maintaining plasmids in cell lines, targets for antibiotics, and as positive selection vectors.[12]

Evolutionary advantage

Plasmid stabilising toxin-antitoxin systems have been used as examples of selfish DNA as part of the gene centered view of evolution. It has been theorised that toxin-antitoxin loci serve only to maintain their own DNA, at the expense of the host organism.[1] Other theories propose the systems have evolved to increase the fitness of plasmids in competition with other plasmids.[13] Thus, the toxin-antitoxin system confers an advantage to the host DNA by eliminating competing plasmids in cell progeny. This theory was corroborated through computer modelling.[14] This does not, however, explain the presence of toxin-antitoxin systems on chromosomes.

Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems have a number of adaptive theories explaining their success at natural selection. The simplest explanation of their existence on chromosomes is that they prevent harmful large deletions of the cell's genome, though arguably deletions of large coding regions are fatal to a daughter cell regardless.[11] MazEF, a toxin-antitoxin locus found in E. coli and other bacteria, induces programmed cell death in response to starvation, specifically a lack of amino acids.[17] This releases the cell's contents for absorption by neighbouring cells, potentially preventing the death of close relatives, and thereby increasing the inclusive fitness of the cell that perished. This is an example of altruism and how bacterial colonies resemble multicellular organisms.[14] However, the "mazEF mediated PCD" is largely refuted by several studies.[18][19][20]

Another theory states that chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems are designed to be bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal.[21] RelE, for example, is a global inhibitor of translation during nutrient stress, and its expression reduces the chance of starvation by lowering the cell's nutrient requirements.[22] A homologue of mazF toxin called mazF-mx is essential for fruiting body formation in Myxococcus xanthus.[23] When nutrients become limiting in this swarming bacteria, a group of 50,000 cells converge into a fruiting body structure.[24] The maxF-mx toxin is a component of this nutrient-stress pathway; it enables a percentage of cells within the fruiting body to form myxospores. It has been suggested that M. xanthus has hijacked the toxin-antitoxin system, replacing the antitoxin with its own molecular control to regulate its development.[23]

It has also been proposed that chromosomal copies of plasmid toxin-antitoxin systems may serve as anti-addiction modules – a method of omitting a plasmid from progeny without suffering the effects of the toxin.[9] An example of this is an antitoxin on the Erwinia chrysanthemi genome that counteracts the toxic activity of an F plasmid toxin counterpart.[25]

Nine possible functions of toxin-antitoxin systems have been proposed. These are:[26][27]

- Junk – they have been acquired from plasmids and retained due to their addictive nature.

- Stabilisation of genomic parasites – chromosomal remnants from transposons and bacteriophages.

- Selfish alleles – non-addictive alleles are unable to replace addictive alleles during recombination but the opposite is able to occur.

- Gene regulation – some toxins act as a means of general repression of gene expression[28] while others are more specific.[29]

- Growth control – bacteriostatic toxins, as mentioned above, restrict growth rather than killing the host cell.[21]

- Persisters – some bacterial populations contain a sub-population of 'persisters' that are slow-growing, hardy individuals, which potentially insure the population against catastrophic loss.[30] At least with regard to endoribonuclease encoding Type II TA systems, their role in persistence is highly debated.[31] What has been demonstrated by experiments and modelling [32] is that an imbalance between the level of toxin and its antitoxin, either by mutations [33][34] or by overexpression[35] results in high persistence.

- Programmed cell arrest and the preservation of the commons – the altruistic explanation as demonstrated by MazEF, detailed above.

- Programmed cell death – similar to the above function, although individuals must have variable stress survival level to prevent entire population destruction.

- Antiphage mechanism – when bacteriophage interrupt the host cell's transcription and translation, a toxin-antitoxin system may be activated that limits the phage's replication.[36][37]

An experiment where five TA systems were deleted from a strain of E. coli found no evidence that the TA systems conferred an advantage to the host. This result casts doubt on the growth control and programmed cell death hypotheses.[38] As of the existing knowledge in 2017, the chromosomal Type II TA systems are horizontally propagating selfish DNA which may have played a role in antiaddiction to TA encoding plasmids.[9][27]

System types

Type I

Type I toxin-antitoxin systems rely on the base-pairing of complementary antitoxin RNA with the toxin's mRNA. Translation of the mRNA is then inhibited either by degradation via RNase III or by occluding the Shine-Dalgarno sequence or ribosome binding site. Often the toxin and antitoxin are encoded on opposite strands of DNA. The 5' or 3' overlapping region between the two genes is the area involved in complementary base-pairing, usually with between 19–23 contiguous base pairs.[39]

Toxins of type I systems are small, hydrophobic proteins that confer toxicity by damaging cell membranes.[1] Few intracellular targets of type I toxins have been identified, possibly due to the difficult nature of analysing proteins that are poisonous to their bacterial hosts.[10]

Type I systems sometimes include a third component. In the case of the well-characterised hok/sok system, in addition to the hok toxin and sok antitoxin, there is a third gene, called mok. This open reading frame almost entirely overlaps that of the toxin, and the translation of the toxin is dependent on the translation of this third component.[3] Thus the binding of antitoxin to toxin is sometimes a simplification, and the antitoxin in fact binds a third RNA, which then affects toxin translation.[39]

Example systems

| Toxin | Antitoxin | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hok | Sok | The original and best-understood type I toxin-antitoxin system (pictured), which stabilises plasmids in a number of gram-negative bacteria | [39] |

| fst | RNAII | The first type I system to be identified in gram-positive bacteria | [40] |

| TisB | IstR | Responds to DNA damage | [41] |

| LdrD | RdlD | A chromosomal system in Enterobacteriaceae | [42] |

| FlmA | FlmB | A hok/sok homologue, which also stabilises the F plasmid | [43] |

| Ibs | Sib | Discovered in E. coli intergenic regions, the antitoxin was originally named QUAD RNA | [44] |

| TxpA/BrnT | RatA | Ensures the inheritance of the skin element during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis | [45] |

| SymE | SymR | A chromosomal system induced as an SOS response | [5] |

| XCV2162 | ptaRNA1 | A system identified in Xanthomonas campestris with erratic phylogenetic distribution. | [46] |

See also

Type II

Type II toxin-antitoxin systems are generally better-understood than type I.[39] In this system a labile protein antitoxin tightly binds and inhibits the activity of a stable toxin.[10] The largest family of type II toxin-antitoxin systems is vapBC,[47] which has been found through bioinformatics searches to represent between 37 and 42% of all predicted type II loci.[15][16]

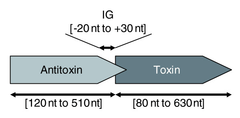

Type II systems are organised in operons with the antitoxin protein typically being located upstream of the toxin, which helps to prevent expression of the toxin without the antitoxin[48]. The proteins are typically around 100 amino acids in length,[39] and exhibit toxicity in a number of ways: CcdB protein, for example, affects DNA gyrase by poisoning DNA topoisomerase II[49] whereas MazF protein is a toxic endoribonuclease that cleaves cellular mRNAs at specific sequence motifs.[50] The most common toxic activity is the protein acting as an endonuclease, also known as an interferase.[51][52]

A third protein can sometimes be involved in type II toxin-antitoxin systems.[53] In the case of the aforementioned MazEF addiction module, in addition to the toxin and antitoxin there is a regulatory protein involved called MazG. MazG protein interacts with E. coli's Era GTPase and is described as a 'nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase,'[54] which hydrolyses nucleoside triphosphates to monophosphates. Later research showed that MazG is transcribed in the same polycistronic mRNA as MazE and MazF, and that MazG bound the MazF toxin to further inhibit its activity.[55]

Unlike the aforementioned toxin-antitoxin systems, DarTG is a considered a type II system, in which both the toxin and the antitoxin have enzymatic activity. The DarG antitoxin does not inhibit the DarT toxin, which modifies DNA by ADP-ribosylating specific sequence motifs, but instead removes the toxic modification caused by the toxin and therefore DarTG could be considered a type IV system.[56]

Example systems

| Toxin | Antitoxin | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CcdB | CcdA | Found on the F plasmid of Escherichia coli | [49] |

| ParE | ParD | Found in multiple copies in Caulobacter crescentus | [57] |

| MazF | MazE | Found in E. coli and in chromosomes of other bacteria | [36] |

| yafO | yafN | A system induced by the SOS response to DNA damage in E. coli | [53] |

| HicA | HicB | Found in archaea and bacteria | [58] |

| Kid | Kis | Stabilises the R1 plasmid and is related to the CcdB/A system | [21] |

| Zeta | Epsilon | Found mostly in Gram-positive bacteria | [59] |

| DarT | DarG | Found in archaea and bacteria | [56] |

Type III

| ToxN_toxin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | ToxN, type III toxin-antitoxin system | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF13958 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Type III toxin-antitoxin systems rely on direct interaction between a toxic protein and an RNA antitoxin. The toxic effects of the protein are neutralised by the RNA gene.[6] One example is the ToxIN system from the bacterial plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora. The toxic ToxN protein is approximately 170 amino acids long and has been shown to be toxic to E. coli. The toxic activity of ToxN is inhibited by ToxI RNA, an RNA with 5.5 direct repeats of a 36 nucleotide motif (AGGTGATTTGCTACCTTTAAGTGCAGCTAGAAATTC).[60][61] Crystallographic analysis of ToxIN has found that ToxN inhibition requires the formation of a trimeric ToxIN complex, whereby three ToxI monomers bind three ToxN monomers; the complex is held together by extensive protein-RNA interactions.[62]

Type IV

Type IV toxin-antitoxin systems are similar to type II systems, because they consist of two proteins. Unlike type II systems, the antitoxin in type IV toxin-antitoxin systems counteracts the activity of the toxin, and the two proteins do not directly interact.[63]

Type V

GhoT/GhoS is a type V toxin-antitoxin system, in which the antitoxin (GhoS) cleaves the ghoT mRNA. This system is regulated by the type II system, MsqR/MsqA.[64]

Type VI

SocAB is a type VI toxin-antitoxin system that was discovered in Caulobacter crescentus. The antitoxin, SocA, promotes degradation of the toxin, SocB, by the protease ClpXP.[65]

Biotechnological applications

The biotechnological applications of toxin-antitoxin systems have begun to be realised by several biotechnology organisations.[12][21] A primary usage is in maintaining plasmids in a large bacterial cell culture. In an experiment examining the effectiveness of the hok/sok locus, it was found that segregational stability of an inserted plasmid expressing beta-galactosidase was increased by between 8 and 22 times compared to a control culture lacking a toxin-antitoxin system.[66][67] In large-scale microorganism processes such as fermentation, progeny cells lacking the plasmid insert often have a higher fitness than those who inherit the plasmid and can outcompete the desirable microorganisms. A toxin-antitoxin system maintains the plasmid thereby maintaining the efficiency of the industrial process.[12]

Additionally, toxin-antitoxin systems may be a future target for antibiotics. Inducing suicide modules against pathogens could help combat the growing problem of multi-drug resistance.[68]

Ensuring a plasmid accepts an insert is a common problem of DNA cloning. Toxin-antitoxin systems can be used to positively select for only those cells that have taken up a plasmid containing the inserted gene of interest, screening out those that lack the inserted gene. An example of this application comes from CcdB-encoded toxin, which has been incorporated into plasmid vectors.[69] The gene of interest is then targeted to recombine into the CcdB locus, inactivating the transcription of the toxic protein. Thus, cells containing the plasmid but not the insert perish due to the toxic effects of CcdB protein, and only those that incorporate the insert survive.[12]

Another example application involves both the CcdB toxin and CcdA antitoxin. CcdB is found in recombinant bacterial genomes and an inactivated version of CcdA is inserted into a linearised plasmid vector. A short extra sequence is added to the gene of interest that activates the antitoxin when the insertion occurs. This method ensures orientation-specific gene insertion.[69]

Genetically modified organisms must be contained in a pre-defined area during research.[68] Toxin-antitoxin systems can cause cell suicide in certain conditions, such as a lack of a lab-specific growth medium they would not encounter outside of the controlled laboratory set-up.[21][70]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Van Melderen L, Saavedra De Bast M (March 2009). Rosenberg SM, ed. "Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: more than selfish entities?". PLoS Genetics. 5 (3): e1000437. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000437. PMC 2654758. PMID 19325885.

- ↑ Gerdes K (February 2000). "Toxin-antitoxin modules may regulate synthesis of macromolecules during nutritional stress". Journal of Bacteriology. 182 (3): 561–72. doi:10.1128/JB.182.3.561-572.2000. PMC 94316. PMID 10633087.

- 1 2 Faridani OR, Nikravesh A, Pandey DP, Gerdes K, Good L (2006). "Competitive inhibition of natural antisense Sok-RNA interactions activates Hok-mediated cell killing in Escherichia coli". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (20): 5915–22. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl750. PMC 1635323. PMID 17065468.

- ↑ Fozo EM, Makarova KS, Shabalina SA, Yutin N, Koonin EV, Storz G (June 2010). "Abundance of type I toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria: searches for new candidates and discovery of novel families". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (11): 3743–59. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq054. PMC 2887945. PMID 20156992.

- 1 2 Gerdes K, Wagner EG (April 2007). "RNA antitoxins". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 10 (2): 117–24. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.003. PMID 17376733.

- 1 2 Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S (May 2010). "Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 8 (5): 317–27. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2315. PMID 20348932.

- ↑ Page R, Peti W (April 2016). "Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacterial growth arrest and persistence". Nature Chemical Biology. 12 (4): 208–14. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2044. PMID 26991085.

- ↑ Mine N, Guglielmini J, Wilbaux M, Van Melderen L (April 2009). "The decay of the chromosomally encoded ccdO157 toxin-antitoxin system in the Escherichia coli species". Genetics. 181 (4): 1557–66. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.095190. PMC 2666520. PMID 19189956.

- 1 2 3 Ramisetty BC, Santhosh RS (February 2016). "Horizontal gene transfer of chromosomal Type II toxin-antitoxin systems of Escherichia coli". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 363 (3). doi:10.1093/femsle/fnv238. PMID 26667220.

- 1 2 3 Hayes F (September 2003). "Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest". Science. 301 (5639): 1496–9. doi:10.1126/science.1088157. PMID 12970556.

- 1 2 Rowe-Magnus DA, Guerout AM, Biskri L, Bouige P, Mazel D (March 2003). "Comparative analysis of superintegrons: engineering extensive genetic diversity in the Vibrionaceae". Genome Research. 13 (3): 428–42. doi:10.1101/gr.617103. PMC 430272. PMID 12618374.

- 1 2 3 4 Stieber D, Gabant P, Szpirer C (September 2008). "The art of selective killing: plasmid toxin/antitoxin systems and their technological applications". BioTechniques. 45 (3): 344–6. doi:10.2144/000112955. PMID 18778262.

- ↑ Cooper TF, Heinemann JA (November 2000). "Postsegregational killing does not increase plasmid stability but acts to mediate the exclusion of competing plasmids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (23): 12643–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.220077897. PMC 18817. PMID 11058151.

- 1 2 Mochizuki A, Yahara K, Kobayashi I, Iwasa Y (February 2006). "Genetic addiction: selfish gene's strategy for symbiosis in the genome". Genetics. 172 (2): 1309–23. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.042895. PMC 1456228. PMID 16299387.

- 1 2 Pandey DP, Gerdes K (2005). "Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes". Nucleic Acids Research. 33 (3): 966–76. doi:10.1093/nar/gki201. PMC 549392. PMID 15718296.

- 1 2 3 Sevin EW, Barloy-Hubler F (2007). "RASTA-Bacteria: a web-based tool for identifying toxin-antitoxin loci in prokaryotes". Genome Biology. 8 (8): R155. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r155. PMC 2374986. PMID 17678530.

- ↑ Aizenman E, Engelberg-Kulka H, Glaser G (June 1996). "An Escherichia coli chromosomal "addiction module" regulated by guanosine [corrected] 3',5'-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (12): 6059–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.12.6059. PMC 39188. PMID 8650219.

- ↑ Ramisetty BC, Natarajan B, Santhosh RS (February 2015). "mazEF-mediated programmed cell death in bacteria: "what is this?"". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 41 (1): 89–100. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2013.804030. PMID 23799870.

- ↑ Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Van Melderen L (September 2007). "What is the benefit to Escherichia coli of having multiple toxin-antitoxin systems in its genome?". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (17): 6101–8. doi:10.1128/JB.00527-07. PMC 1951899. PMID 17513477.

- ↑ Ramisetty BC, Raj S, Ghosh D (December 2016). "Escherichia coli MazEF toxin-antitoxin system does not mediate programmed cell death". Journal of Basic Microbiology. 56 (12): 1398–1402. doi:10.1002/jobm.201600247. PMID 27259116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diago-Navarro E, Hernandez-Arriaga AM, López-Villarejo J, Muñoz-Gómez AJ, Kamphuis MB, Boelens R, Lemonnier M, Díaz-Orejas R (August 2010). "parD toxin-antitoxin system of plasmid R1--basic contributions, biotechnological applications and relationships with closely-related toxin-antitoxin systems". The FEBS Journal. 277 (15): 3097–117. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07722.x. PMID 20569269.

- ↑ Christensen SK, Mikkelsen M, Pedersen K, Gerdes K (December 2001). "RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (25): 14328–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.251327898. PMC 64681. PMID 11717402.

- 1 2 Nariya H, Inouye M (January 2008). "MazF, an mRNA interferase, mediates programmed cell death during multicellular Myxococcus development". Cell. 132 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.044. PMID 18191220.

- ↑ Curtis PD, Taylor RG, Welch RD, Shimkets LJ (December 2007). "Spatial organization of Myxococcus xanthus during fruiting body formation". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (24): 9126–30. doi:10.1128/JB.01008-07. PMC 2168639. PMID 17921303.

- ↑ Saavedra De Bast M, Mine N, Van Melderen L (July 2008). "Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems may act as antiaddiction modules". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (13): 4603–9. doi:10.1128/JB.00357-08. PMC 2446810. PMID 18441063.

- ↑ Magnuson RD (September 2007). "Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (17): 6089–92. doi:10.1128/JB.00958-07. PMC 1951896. PMID 17616596.

- 1 2 Ramisetty BC, Santhosh RS (July 2017). "Endoribonuclease type II toxin-antitoxin systems: functional or selfish?". Microbiology. 163 (7): 931–939. doi:10.1099/mic.0.000487. PMID 28691660.

- ↑ Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R (October 2006). "Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria". PLoS Genetics. 2 (10): e135. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. PMC 1626106. PMID 17069462.

- ↑ Pimentel B, Madine MA, de la Cueva-Méndez G (October 2005). "Kid cleaves specific mRNAs at UUACU sites to rescue the copy number of plasmid R1". The EMBO Journal. 24 (19): 3459–69. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600815. PMC 1276173. PMID 16163387.

- ↑ Kussell E, Kishony R, Balaban NQ, Leibler S (April 2005). "Bacterial persistence: a model of survival in changing environments". Genetics. 169 (4): 1807–14. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.035352. PMC 1449587. PMID 15687275.

- ↑ Ramisetty BC, Ghosh D, Roy Chowdhury M, Santhosh RS (2016). "What Is the Link between Stringent Response, Endoribonuclease Encoding Type II Toxin-Antitoxin Systems and Persistence?". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 1882. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01882. PMC 5120126. PMID 27933045.

- ↑ Rotem E, Loinger A, Ronin I, Levin-Reisman I, Gabay C, Shoresh N, Biham O, Balaban NQ (July 2010). "Regulation of phenotypic variability by a threshold-based mechanism underlies bacterial persistence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (28): 12541–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004333107. PMC 2906590. PMID 20616060.

- ↑ Moyed HS, Bertrand KP (August 1983). "Mutations in multicopy Tn10 tet plasmids that confer resistance to inhibitory effects of inducers of tet gene expression". Journal of Bacteriology. 155 (2): 557–64. PMC 217723. PMID 6307969.

- ↑ Fridman O, Goldberg A, Ronin I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ (September 2014). "Optimization of lag time underlies antibiotic tolerance in evolved bacterial populations". Nature. 513 (7518): 418–21. doi:10.1038/nature13469. PMID 25043002.

- ↑ Korch SB, Hill TM (June 2006). "Ectopic overexpression of wild-type and mutant hipA genes in Escherichia coli: effects on macromolecular synthesis and persister formation". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (11): 3826–36. doi:10.1128/JB.01740-05. PMC 1482909. PMID 16707675.

- 1 2 Hazan R, Engelberg-Kulka H (September 2004). "Escherichia coli mazEF-mediated cell death as a defense mechanism that inhibits the spread of phage P1". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 272 (2): 227–34. doi:10.1007/s00438-004-1048-y. PMID 15316771.

- ↑ Pecota DC, Wood TK (April 1996). "Exclusion of T4 phage by the hok/sok killer locus from plasmid R1". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (7): 2044–50. doi:10.1128/jb.178.7.2044-2050.1996. PMC 177903. PMID 8606182.

- ↑ Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Van Melderen L (September 2007). "What is the benefit to Escherichia coli of having multiple toxin-antitoxin systems in its genome?". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (17): 6101–8. doi:10.1128/JB.00527-07. PMC 1951899. PMID 17513477.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fozo EM, Hemm MR, Storz G (December 2008). "Small toxic proteins and the antisense RNAs that repress them". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 72 (4): 579–89, Table of Contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00025-08. PMC 2593563. PMID 19052321.

- ↑ Greenfield TJ, Ehli E, Kirshenmann T, Franch T, Gerdes K, Weaver KE (August 2000). "The antisense RNA of the par locus of pAD1 regulates the expression of a 33-amino-acid toxic peptide by an unusual mechanism". Molecular Microbiology. 37 (3): 652–60. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02035.x. PMID 10931358. (subscription required)

- ↑ Vogel J, Argaman L, Wagner EG, Altuvia S (December 2004). "The small RNA IstR inhibits synthesis of an SOS-induced toxic peptide". Current Biology. 14 (24): 2271–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.003. PMID 15620655.

- ↑ Kawano M, Oshima T, Kasai H, Mori H (July 2002). "Molecular characterization of long direct repeat (LDR) sequences expressing a stable mRNA encoding for a 35-amino-acid cell-killing peptide and a cis-encoded small antisense RNA in Escherichia coli". Molecular Microbiology. 45 (2): 333–49. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03042.x. PMID 12123448. (subscription required)

- ↑ Loh SM, Cram DS, Skurray RA (June 1988). "Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of a third function (Flm) involved in F-plasmid maintenance". Gene. 66 (2): 259–68. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(88)90362-9. PMID 3049248.

- ↑ Fozo EM, Kawano M, Fontaine F, Kaya Y, Mendieta KS, Jones KL, Ocampo A, Rudd KE, Storz G (December 2008). "Repression of small toxic protein synthesis by the Sib and OhsC small RNAs". Molecular Microbiology. 70 (5): 1076–93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06394.x. PMC 2597788. PMID 18710431. (subscription required)

- ↑ Silvaggi JM, Perkins JB, Losick R (October 2005). "Small untranslated RNA antitoxin in Bacillus subtilis". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (19): 6641–50. doi:10.1128/JB.187.19.6641-6650.2005. PMC 1251590. PMID 16166525.

- ↑ Findeiss S, Schmidtke C, Stadler PF, Bonas U (March 2010). "A novel family of plasmid-transferred anti-sense ncRNAs". RNA Biology. 7 (2): 120–4. doi:10.4161/rna.7.2.11184. PMID 20220307.

- ↑ Robson J, McKenzie JL, Cursons R, Cook GM, Arcus VL (July 2009). "The vapBC operon from Mycobacterium smegmatis is an autoregulated toxin-antitoxin module that controls growth via inhibition of translation". Journal of Molecular Biology. 390 (3): 353–67. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.006. PMID 19445953.

- ↑ Deter HS, Jensen RV, Mather WH, Butzin NC (July 2017). "Mechanisms for Differential Protein Production in Toxin-Antitoxin Systems". Toxins. 9 (7): 211. doi:10.3390/toxins9070211. PMC 5535158. PMID 28677629.

- 1 2 Bernard P, Couturier M (August 1992). "Cell killing by the F plasmid CcdB protein involves poisoning of DNA-topoisomerase II complexes". Journal of Molecular Biology. 226 (3): 735–45. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(92)90629-X. PMID 1324324.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hoeflich KP, Ikura M, Qing G, Inouye M (October 2003). "MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli". Molecular Cell. 12 (4): 913–23. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00402-7. PMID 14580342.

- ↑ Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Overgaard M, Winther KS, Gerdes K (2008). "RNA decay by messenger RNA interferases". Methods in Enzymology. Methods in Enzymology. 447: 521–35. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02225-8. ISBN 978-0-12-374377-0. PMID 19161859.

- ↑ Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M (2009). "mRNA interferases, sequence-specific endoribonucleases from the toxin-antitoxin systems". Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 85: 467–500. doi:10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00812-X. ISBN 978-0-12-374761-7. PMID 19215780.

- 1 2 Singletary LA, Gibson JL, Tanner EJ, McKenzie GJ, Lee PL, Gonzalez C, Rosenberg SM (December 2009). "An SOS-regulated type 2 toxin-antitoxin system". Journal of Bacteriology. 191 (24): 7456–65. doi:10.1128/JB.00963-09. PMC 2786605. PMID 19837801.

- ↑ Zhang J, Inouye M (October 2002). "MazG, a nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase, interacts with Era, an essential GTPase in Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology. 184 (19): 5323–9. doi:10.1128/JB.184.19.5323-5329.2002. PMC 135369. PMID 12218018.

- ↑ Gross M, Marianovsky I, Glaser G (January 2006). "MazG -- a regulator of programmed cell death in Escherichia coli". Molecular Microbiology. 59 (2): 590–601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04956.x. PMID 16390452. (subscription required)

- 1 2 Jankevicius G, Ariza A, Ahel M, Ahel I (December 2016). "The Toxin-Antitoxin System DarTG Catalyzes Reversible ADP-Ribosylation of DNA". Molecular Cell. 64 (6): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.014. PMC 5179494. PMID 27939941.

- ↑ Fiebig A, Castro Rojas CM, Siegal-Gaskins D, Crosson S (July 2010). "Interaction specificity, toxicity and regulation of a paralogous set of ParE/RelE-family toxin-antitoxin systems". Molecular Microbiology. 77 (1): 236–51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07207.x. PMC 2907451. PMID 20487277. (subscription required)

- ↑ Jørgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K (February 2009). "HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea". Journal of Bacteriology. 191 (4): 1191–9. doi:10.1128/JB.01013-08. PMC 2631989. PMID 19060138.

- ↑ Mutschler H, Meinhart A (December 2011). "ε/ζ systems: their role in resistance, virulence, and their potential for antibiotic development". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 89 (12): 1183–94. doi:10.1007/s00109-011-0797-4. PMC 3218275. PMID 21822621.

- ↑ Fineran PC, Blower TR, Foulds IJ, Humphreys DP, Lilley KS, Salmond GP (January 2009). "The phage abortive infection system, ToxIN, functions as a protein-RNA toxin-antitoxin pair". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (3): 894–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808832106. PMC 2630095. PMID 19124776.

- ↑ Blower TR, Fineran PC, Johnson MJ, Toth IK, Humphreys DP, Salmond GP (October 2009). "Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the RNA and protein components of the toxIN abortive infection and toxin-antitoxin locus of Erwinia". Journal of Bacteriology. 191 (19): 6029–39. doi:10.1128/JB.00720-09. PMC 2747886. PMID 19633081.

- ↑ Blower TR, Pei XY, Short FL, Fineran PC, Humphreys DP, Luisi BF, Salmond GP (February 2011). "A processed noncoding RNA regulates an altruistic bacterial antiviral system". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 18 (2): 185–90. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1981. PMC 4612426. PMID 21240270.

- ↑ Brown JM, Shaw KJ (November 2003). "A novel family of Escherichia coli toxin-antitoxin gene pairs". Journal of Bacteriology. 185 (22): 6600–8. doi:10.1128/jb.185.22.6600-6608.2003. PMC 262102. PMID 14594833.

- ↑ Wang X, Lord DM, Hong SH, Peti W, Benedik MJ, Page R, Wood TK (June 2013). "Type II toxin/antitoxin MqsR/MqsA controls type V toxin/antitoxin GhoT/GhoS". Environmental Microbiology. 15 (6): 1734–44. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12063. PMC 3620836. PMID 23289863.

- ↑ Aakre CD, Phung TN, Huang D, Laub MT (December 2013). "A bacterial toxin inhibits DNA replication elongation through a direct interaction with the β sliding clamp". Molecular Cell. 52 (5): 617–28. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.014. PMC 3918436. PMID 24239291.

- ↑ Wu K, Jahng D, Wood TK (1994). "Temperature and growth rate effects on the hok/sok killer locus for enhanced plasmid stability". Biotechnology Progress. 10 (6): 621–9. doi:10.1021/bp00030a600. PMID 7765697.

- ↑ Pecota DC, Kim CS, Wu K, Gerdes K, Wood TK (May 1997). "Combining the hok/sok, parDE, and pnd postsegregational killer loci to enhance plasmid stability". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 63 (5): 1917–24. PMC 168483. PMID 9143123.

- 1 2 Gerdes K, Christensen SK, Løbner-Olesen A (May 2005). "Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 3 (5): 371–82. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1147. PMID 15864262.

- 1 2 Bernard P, Gabant P, Bahassi EM, Couturier M (October 1994). "Positive-selection vectors using the F plasmid ccdB killer gene". Gene. 148 (1): 71–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90235-6. PMID 7926841.

- ↑ Torres B, Jaenecke S, Timmis KN, García JL, Díaz E (December 2003). "A dual lethal system to enhance containment of recombinant micro-organisms". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 12): 3595–601. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26618-0. PMID 14663091.

Further reading

- Wen J, Won D, Fozo EM (February 2014). "The ZorO-OrzO type I toxin-antitoxin locus: repression by the OrzO antitoxin". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (3): 1930–46. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1018. PMC 3919570. PMID 24203704.

External links

- RASTA – Rapid Automated Scan for Toxins and Antitoxins in Bacteria