Planet Hunters

Planet Hunters is a citizen science project to find planets using human eyes. It does this by having users analyze data from the NASA Kepler Space Mission.[1] It was launched by a team led by Debra Fischer at Yale University,[2] as part of the Zooniverse project.[3]

Planet hunting

The Planet Hunters project exploits the fact that humans are better at recognising visual patterns than computers. The website displays an image of data collected by the NASA Kepler Space Mission and asks human users (referred to as "Citizen Scientists") to look at the data and see how the brightness of a star changes over time. This brightness data is represented as a graph and referred to as a star's light curve. Such curves are helpful in discovering extrasolar planets due to the brightness of a star decreasing when a planet passes in front of it, as seen from Earth.[4] Periods of reduced brightness can thus provide evidence of planetary transits, but may also be caused by errors in recording, projection, or other phenomena.[5]

Sorting the light curves

Users are asked to sort the light curves based on the patterns. The patterns available are "quiet" and "variable". When the light curve is quiet, the graph mostly follows a straight path. When the light curve is variable, there are a number of things that it can do. It can be "regular", "pulsating", or "irregular".[6] A regular light curve means it goes up once and down once, reaching an apex and descending. A pulsating light curve means it goes up and down along the y-axis on a rather steep basis. An irregular light curve has points that go up and down on the y-axis in an unpredictable pattern.

Special occurrence

Eclipsing binary stars

From time to time, the project will observe eclipsing binary stars. Essentially these are stars that orbit each other. Much as a planet can interrupt the brightness of a star, another star can too. There is a noticeable difference on the light curves. It will appear as a large transit (a large dip) and a smaller transit (a smaller dip).[7][8]

Multiplanet systems

As of December 2017, there are a total of 621 multiplanetary stars, or stars that contains at least two confirmed planets.[9] In a multiplanet system plot, there are many different patterns of transit. Due to the different sizes of planets, the transits dip down to different points.[10]

Stellar flares

Stellar flares are observed when there is an explosion on the surface of a star. This will cause the star's brightness to shoot up considerably, with a steep drop off.[11]

Discoveries

So far, over 12 million observations have been analyzed. Out of those, 34 candidate planets had been found as of July 2012.[12] In October 2012 it was announced that two volunteers from the Planet Hunters initiative had discovered a novel Neptune-like planet which is part of a four star double binary system, orbiting one of the pairs of stars while the other pair of stars orbits at a distance of around 1000 AU. This is the first planet discovered to have a stable orbit in such a complex stellar environment. The system is located just under 5000 light years away, and the new planet has been designated PH1, short for Planet Hunters 1.[13][14]

Yellow rows indicate a circumbinary planet. Light green rows indicate planet orbiting around one star in a multiple star system.

| Planet | Mass (MJ) |

Radius (RJ) |

Orbital period (d) |

Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital ecc. |

Inclin. (°) |

Star | Constell. |

App. mag. |

Distance (ly) |

Spectral type |

Year of confirmation | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH1 (Kepler-64b) | 0.08-0.14 | 0.551 | 138.506 | 0.634 | 0.0539 | 90.022 | kepler-64 | Cygnus | 13.718 | ~5000 | F/M | 2012 | |

| PH2 (Kepler-86b) | 0.85-0.95 | 282.5255 | 0.828 | 0.12-0.49 | 89.83 | kepler-86 | Cygnus | 1206 | ~G4 | 2013 | |||

| PH3 (Kepler-289c) | Kepler-289 | 2014 |

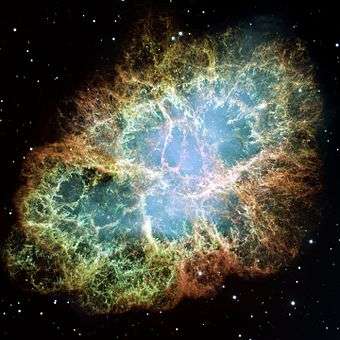

Furthermore, the unusual light curve of KIC 8462852 (also known as Tabby's Star)[15] has engendered speculation that an alien civilization's Dyson sphere[16][17] is responsible.[18]

See also

Zooniverse projects:

References

- ↑ "What is Planet Hunters". Planet Hunters website. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ http://news.yale.edu/2010/12/16/citizen-scientists-join-search-earth-planets

- ↑ "The Zooniverse". Zooniverse website. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Administrator, NASA Content (2015-04-16). "Light Curve of a Planet Transiting Its Star". NASA. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Planet Hunting Tutorial". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Sorting the Light Curves". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Eclipsing Binary Stars". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Eclipsing Binary Light Curves". imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ Schneider, Jean (16 December 2017). "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Multiplanet Systems". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Stellar Flares". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Planetometer". Planet Hunters website. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Planet with four suns discovered by volunteers". BBC. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Schwamb, Megan E.; Orosz, Jerome A.; Carter, Joshua A.; Welsh, William F.; Fischer, Debra A.; Torres, Guillermo; Howard, Andrew W.; Crepp, Justin R.; Keel, William C.; et al. (2012). "Planet Hunters: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet in a Quadruple Star System". 1210: 3612. arXiv:1210.3612. Bibcode:2013ApJ...768..127S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/2/127.

- ↑ Boyajian, T. S.; et al. (27 January 2016). "Planet Hunters X: KIC 8462852 – Where's the flux?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 457 (4): 3988–4004. arXiv:1509.03622. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.457.3988B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw218.

- ↑ Bodenner, Chris (16 October 2015). "Maybe It's a Dyson Sphere". Notes. The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ↑ Bodenner, Chris (17 October 2015). "Maybe It's a Dyson Sphere, Cont'd". Notes. The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ↑ Andersen, Ross (13 October 2015). "The Most Mysterious Star in Our Galaxy". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 June 2017.