Philippine peso

| Philippine peso | |

|---|---|

| Piso ng Pilipinas (Filipino) | |

New Generation Currency banknotes, in current circulation. | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | PHP |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | Sentimo or centavo |

| Symbol | ₱ |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | ₱20, ₱50, ₱100, ₱500, ₱1000 |

| Rarely used | ₱200 |

| Coins | |

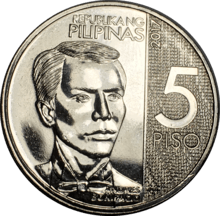

| Freq. used | ₱1, ₱5, ₱10 |

| Rarely used | 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) |

|

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas |

| Website |

www |

| Printer | The Security Plant Complex |

| Website |

www |

| Mint | The Security Plant Complex |

| Website |

www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 5.2%[1] |

| Source | Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, June 2018 |

| Method | CPI |

The Philippine peso, also referred to by its Filipino name piso (Philippine English: /ˈpɛsoʊ/, /ˈpiː-/, plural pesos; Filipino: piso [ˈpiso, pɪˈso]; sign: ₱; code: PHP), is the official currency of the Philippines. It is subdivided into 100 centavos or sentimos in Filipino. As a former colony of the United States, the country used English on its currency, with the word "peso" appearing on notes and coinage until 1967. Since the adoption of the usage of the Filipino language on banknotes and coins, the term "piso" is now used. From September 2017 to 2 August 2018, the ISO 4217 standard referred to the currency by the Filipino term "piso".[2] It has since been changed back to "peso".[3]

The peso is usually denoted by the symbol "₱". Other ways of writing the Philippine peso sign are "PHP", "PhP", "Php", or just "P". The "₱" symbol was added to the Unicode standard in version 3.2 and is assigned U+20B1 (₱). The symbol can be accessed through some word processors by typing in "20b1" and then pressing the Alt and X buttons simultaneously.[4] This symbol is unique to the Philippines as the symbol used for the peso in countries like Mexico and other former colonies of Spain in Latin America is "$".

Banknotes and coins of the Philippines are minted and printed at the Security Plant Complex of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Central Bank of the Philippines) in Quezon City.[5][6]

History

Pre-colonial coinage

The trade the pre-colonial tribes of what is now the Philippines did among themselves with its many types of pre-Hispanic kingdoms (kedatuans, rajahnates, wangdoms, lakanates and sultanates) and with traders from the neighboring islands was conducted through barter. The inconvenience of barter however later led to the use of some objects as a medium of exchange. Gold, which was plentiful in many parts of the islands, invariably found its way into these objects that included the Piloncitos, small bead-like gold bits considered by the local numismatists as the earliest coin of the ancient peoples of the Philippines, and gold barter rings.[7]

Spanish colonial period

The Spaniards brought their coined money when they came in 1521 and the first European coin which reaches the Philippine Islands with Ferdinand Magellan's arrival was the teston or four-reales silver coin. The teston became the de facto unit of trade between Spaniards and Filipinos before the founding of Manila in 1574. The native Tagalog name for the coin was salapi ("money").

Pre-decimal coinage

With the establishment of Spanish Manila in the late 16th century, the Spanish introduced the silver real de a ocho, already known across the Spanish Empire colloquially as the peso, which was divided into 8 reales and further subdivided into 4 cuartos or 8 octavos.

The monetary situation in the Philippine Islands was chaotic due to the circulation of many types of coins, with differing purity and weights, coming from mints across the Spanish-speaking world. Spanish coins circulated freely with those from the newly independent Spanish colonies including reales fuertes, reales de vellón, peseta columnaria, peseta sencilla, pesos de minas, tomines, ducados, maravedis among others. Value equivalents of the different monetary systems were usually difficult to comprehend and hindered trade and commerce.

Decimal coinage

An attempt to remedy the monetary confusion was made in 1848, with the introduction of the decimal system in 1857 under the second Isabelline monetary system.[8] Overseeing the conversion was Fernándo Norzagaray y Escudero, governor general in the period 1857-60.

Conversion to the decimal system with the peso fuerte (Spanish for strong peso) as the unit of account solved the accounting problem, but did little to remedy the confusion of differing circulating coinage. Renewed calls for the Philippine Islands to have a proper mint and monetary system finally came to fruition in September 1857, when Queen Isabel II authorized the creation of the Casa de Moneda de Manila and purchase of required machinery. The mint was inaugurated on March 19, 1861.

Despite the mintage of gold and silver coins, Mexican and South and Central American silver still circulated widely.

The Isabella peso or peso fuerte

.jpg)

The Isabelline peso, more formally known as the peso fuerte, was a unit of account divided into 100 céntimos (equivalent to 8 reales fuertes or 80 reales de vellón). Its introduction led to the Philippines' brief experiment with the gold standard, which would not again be attempted until the American colonial period. The peso fuerte was also a unit of exchange equivalent to 1.69 grams of gold, 0.875 fine (0.0476 XAU), equivalent to ₱1,390.87 (refers to the modern peso; as of September 2015).[9]

Coin production at the Casa de Moneda de Manila began in 1861 with gold coins (0.875 fine) of three denominations: 1 peso, 2 pesos, and 4 pesos. On March 5, 1862, Isabel II granted the mint permission to produce silver fractional coinage (0.900 fine) in denominations of 10, 20, and 50 centimos de peso. Minting of these coins started in 1864, with designs similar to the Spanish silver escudo.

The Alfonso peso, the Spanish-Filipino peso

The currency in the Philippines was standardized by the Spanish government with the minting of a silver peso expressly for use in the colony and firmly reestablishing the silver standard as the Philippine monetary system. The coin, which was to be later known as the Spanish-Filipino peso, was minted in Madrid in 1897 and bore the bust of King Alfonso XIII. The specifications of the coin was 25 grams of silver .900 fine. This configuration was also used in the creation of the Puerto Rican provincial peso in 1895 giving both coins the equivalency of 5 pesetas.[10]

The new monetary standard finally established the peso as 25 grams silver, 0.900 fine (0.7234 XAG), equivalent to ₱942.535 modern pesos of as of 22 December 2010.[11]

The Spanish-Filipino peso remained in circulation and were legal tender in the islands until 1904, when the American authorities demonetized them in favor of the new US-Philippine peso.

Revolutionary Period

Asserting its independence after the Philippine Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898, the República Filipina (Philippine Republic) under General Emilio Aguinaldo issued its own coins and paper currency backed by the country’s natural resources. The coins were the first to use the name centavo for the subdivision of the peso. The island of Panay also issued revolutionary coinage. After Aguinaldo's capture by American forces in Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901, the revolutionary peso ceased to exist.

American Colonial Period

_50_Centavos_Silver_Coin_1918_(s).jpg)

After the United States took control of the Philippines, the United States Congress passed the Philippine Coinage Act of 1903, established the unit of currency to be a theoretical gold peso (not coined) consisting of 12.9 grains of gold 0.900 fine (0.026875 XAU), equivalent to ₱2,933.07 modern pesos of as of 22 December 2010.[12] This unit was equivalent to exactly half the value of a U.S. dollar[13] and maintained its purchasing power until the opening day of the Central Bank of the Philippines in 1949.

The act provided for the coinage and issuance of Philippine silver pesos substantially of the weight and fineness as the Mexican peso, which should be of the value of 50 cents gold and redeemable in gold at the insular treasury, and which was intended to be the sole circulating medium among the people. The act also provided for the coinage of subsidiary and minor coins and for the issuance of silver certificates in denominations of not less than 2 nor more than 10 pesos.

It also provided for the creation of a gold-standard fund to maintain the parity of the coins so authorized to be issued and authorized the insular government to issue temporary certificates of indebtedness bearing interest at a rate not to exceed 4 per cent per annum, payable not more than one year from date of issue, to an amount which should not at any one time exceed 10 million dollars or 20 million pesos.

Commonwealth Period

.jpg)

When Philippines became a U.S. Commonwealth in 1935, the coat of arms of the Philippine Commonwealth were adopted and replaced the arms of the US Territories on the reverse of coins while the obverse remained unchanged. This seal is composed of a much smaller eagle with its wings pointed up, perched over a shield with peaked corners, above a scroll reading "Commonwealth of the Philippines". It is a much busier pattern, and widely considered less attractive.

World War II

In 1942, the Japanese occupiers introduced fiat notes for use in the Philippines. Emergency circulating notes (also termed "guerrilla pesos") were also issued by banks and local governments, using crude inks and materials, which were redeemable in silver pesos after the end of the war. The puppet state under José P. Laurel outlawed possession of guerrilla currency and declared a monopoly on the issuance of money and anyone found to possess guerrilla notes could be arrested or even executed. Because of the fiat nature of the currency, the Philippine economy felt the effects of hyperinflation.

Combined U.S. and Philippine Commonwealth military forces including recognized guerrilla units continued printing Philippine pesos, so that, from October 1944 to September 1945, all earlier issues except for the emergency guerrilla notes were considered illegal and were no longer legal tender.

Independence

.jpg)

Republic Act No. 265 created the Central Bank of the Philippines (now the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas) on January 3, 1949, in which was vested the power of administering the banking and credit system of the country. Under the act, all powers in the printing and mintage of Philippine currency was vested in the CBP, taking away the rights of the banks such as Bank of the Philippine Islands and the Philippine National Bank to issue currency.[14]

In a repeat of Japanese wartime monetary policy, the government defaulted on its promises to redeem its banknotes in silver or gold coin while promising to maintain the two-to-one peso to dollar parity. This decision, compounded with the deliberate overprinting of fiat banknotes, resulted in the peso dropping in value by almost 67% against the US dollar within the first three hours of opening day. The government effort to maintain the peg devastated the gold, silver and dollar reserves of the country.

By 1964, the bullion value of the old silver pesos was worth almost twelve times their face value and were being hoarded by Filipinos rather than being surrendered to the government at face value. In desperation, then-President Diosdado Macapagal demonetized the old silver coins and floated the currency. The peso has been a floating currency ever since, which means that the currency is a physical representation of the domestic debt and whose value directly tied to people's perception of the stability of the current regime and its ability to repay the debt.[15]

In 1967, coinage adopted Filipino language terminology instead of English, banknotes following suit in 1969. Consecutively, the currency terminologies as appearing on coinage and banknotes changed from the English centavo and peso to the Filipino sentimo and piso. However, centavo is more commonly used by Filipinos in everyday speech.

From the opening of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in 1993, successive governments have continued to devalue the currency to lower the accumulated domestic debt in real terms, which in December 2005 reached ₱4.02 trillion.

Current economy

Based on the current price of gold, the Philippine peso has now lost 99% of its original 1903–1949 value. As of September, 2015, it takes ₱1,390.87 to equal the intrinsic purchasing power parity of the 1903–1949 Philippine Commonwealth peso, as per its legal definition: 12.9 grains of pure gold (or 0.026875 XAU).[16]

Names for different denominations

The smallest currency unit is called centavo in English (from Spanish centavo). Following the adoption of the "Pilipino series" in 1967, it became officially known as sentimo in Filipino (from Spanish céntimo).[17] However, "centavo" and its local spellings, síntabo and sentabo, are still used as synonyms in Tagalog. It is the most widespread preferred term over sentimo in other Philippine languages, including Abaknon,[18] Bikol,[19] Cebuano,[20][21] Cuyonon,[22] Ilocano,[23] and Waray,[18] In Chavacano, centavos are referred to as céns (also spelled séns).[24]

Coins

The American government deemed it more economical and convenient to mint silver coins in the Philippines, hence, the re-opening of the Manila Mint in 1920, which produced coins until the Commonwealth Era.

In 1937, coin designs were changed to reflect the establishment of the Commonwealth. During the Second World War, no coins were minted from 1942 to 1943 due to the Japanese Occupation. Minting resumed in 1944, including production of 50-centavo coins. Due to the large number of coins issued between 1944 and 1947, coins were not minted again until 1958.

In 1958, new coinage entirely of base metal was introduced, consisting of bronze 1 centavo, brass 5 centavos and nickel-brass 10, 25 and 50 centavos. In 1967, the coinage was altered to reflect the use of Filipino names for the currency units. One-peso coins were introduced in 1972. In 1975, the Ang Bagong Lipunan Series was introduced with a new 5-peso coin included. Aluminium replaced bronze, and cupro-nickel replaced nickel-brass that year. The Flora and Fauna series was introduced in 1983 which included 2-peso coins. The sizes of the coins were reduced in 1991, with production of 50-centavo and 2-peso coins ceasing in 1994. The current series of coins was introduced in 1995, with 10-peso coins added in 2000.

Denominations below 1 peso are still issued but are not in wide use. In December 2008, House Resolution No. 898 was proposed to call for the retirement and demonetization of all coins less than one peso in value due to the high cost of manufacturing these coins.[25]

Banknotes

In 1949, the Central Bank of the Philippines took over paper money issue. Its first notes were overprints on the Victory Treasury Certificates. These were followed in 1951 by regular issues in denominations of 5, 10, 20 and 50 centavos, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 pesos. The centavo notes (except for the 50-centavo note, which would be later known as the half-peso note) were discontinued in 1958 when the English Series coins were first minted.

In 1967, the CBP adopted the Filipino language on its currency, using the name Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, and in 1969 introduced the "Pilipino Series" of notes in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos. The "Ang Bagong Lipunan Series" was introduced in 1973 and included 2-peso notes. A radical change occurred in 1985, when the CBP issued the "New Design Series" with 500-peso notes introduced in 1987, 1,000-peso notes (for the first time) in 1991 and 200-peso notes in 2002.

The "New Design Series" was the name used to refer to Philippine banknotes issued from 1985 to 1993. It was then renamed into the "BSP Series" due to the re-establishment of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas from 1993 to 2010. It was succeeded by the "New Generation Currency" series issued on December 16, 2010.

The New Design/BSP Series banknotes were still in print until 2013. Existing banknotes remained legal tender until the start of the demonetization process on January 1, 2015. The bills were originally to be demonetized by January 1, 2017,[26][27][28][29][30][31] but the deadline for exchanging the old banknotes was extended twice, on June 30, 2017 and December 29, 2017. After that date, all NDS/BSP banknotes were demonetized and are no longer a liability of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas.[32][33]

New Generation Currency (current)

.jpg)

In 2009, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) announced that it has launched a massive redesign for current banknotes and coins to further enhance security features and improve durability.[34] The members of the numismatic committee include BSP Deputy Governor Diwa Guinigundo and Ambeth Ocampo, Chairman of the National Historical Institute. The new banknote designs feature famous Filipinos and iconic natural wonders. Philippine national symbols will be depicted on coins. The BSP started releasing the initial batch of new banknotes in December 2010.

Several, albeit disputable, errors have been discovered on banknotes of the New Generation series and have become the subject of ridicule over social media sites. Among these are the exclusion of Batanes from the Philippine map on the reverse of all denominations, the mislocation of the Puerto Princesa Subterranean Underground River on the reverse of the 500-peso bill and the Tubbataha Reef on the 1000-peso bill, and the incorrect coloring on the beak and feathers of the blue-naped parrot on the 500-peso bill,[35][36] but these were eventually realized to be due to the color limitations of intaglio printing.[37] The scientific names of the animals featured on the reverse sides of all banknotes were incorrectly rendered as well.[38]

By February 2016, the BSP started to circulate new 100-peso bills which were modified to have a stronger mauve or violet color. This was “in response to suggestions from the public to make it easier to distinguish from the 1000-peso bank note.” The public could still use the New Generation Currency 100-peso bills with fainter colors as they are still acceptable.[39]

Exchange rates

Historical exchange rate

In the 1950s, the exchange rate was 2 pesos against the U.S. dollar. The fluctuating free rate was abolished in 1965, resulting in 3.57 pesos to the dollar, and then 6.40 pesos to the dollar. Several devaluations were followed, with the peso trading at 18 per dollar in 1984 from the dirty float at 11.25 [40] and 21 to the dollar in 1986. In the early 1990s, the peso devalued again to 28 per dollar. Due to the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the peso devalued from 29 per dollar in July 1997 to 46.50 in 1998 and about 50 in 2001.

Current exchange rate

| Current PHP exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From XE: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

Recent issues

Misspelled banknotes

In 2005, About 78 million 100-peso notes with President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s surname misspelt as "Arrovo" were printed and planned to be circulated. The error was only found out after 2 million of the notes were circulated and the BSP had ordered an investigation.[41][42][43]

1-peso coin fraud

By August 2006, it became publicly known that the 1-peso coin has the same size as the 1 United Arab Emirates dirham coin.[44] As of 2010, 1-peso is only worth 7 fils (0.07 dirham), leading to vending machine fraud in the UAE. Similar frauds have also occurred in the US, as the 1-peso coin is roughly the same size as the quarter but as of 2017 is worth slightly less than 2 U.S. cents. Newer digital parking meters are not affected by the fraud, though most vending machines will accept them as quarters.

1971 1-peso coin

In 2017, a one-peso coin that was allegedly minted in 1971 was said to bear the design of the novel Noli Me Tángere by Jose Rizal at the back of the coin. The coin was sold for up to PHP 1,000,000. The holder of the said coin was interviewed by Kapuso Mo, Jessica Soho about this, but the BSP said that it did not release any coin of the said design. The BSP also mentioned that the coin is thinner than the circulating coin which gives the possibility that someone might have tampered it and replaced it with a different design.[45]

Faceless banknotes

In December 2017, a 100 peso banknote which had no face of Manuel A. Roxas and no electrotype 100 was issued. The Facebook post was shared over 24,000 times. The BSP said that the banknotes are due to a rare misprint.[46][47]

10,000 peso banknote

In June 2018, a Facebook page posted a 10,000-peso note with a portrait of President Ramon Magsaysay on the front and a water buffalo and Mount Pinatubo on the back. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas did not issue this banknote and stressed that only 6 denominations are in current circulation (20-, 50-, 100-, 200-, 500- and 1000 pesos). The Facebook page of the BSP said that it was fake. The signature was also of former governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Amando Tetangco Jr..[48]It was found out that the photo was from a different user who found a fake 10,000 peso banknote in a book at a library.

Peso drops past ₱54 amid market jitters

In September 2018, the value of the Philippine peso dropped from ₱54 to a dollar. This is the lowest it has been in almost 13 years due to an ongoing rout against emerging market currencies and a stubbornly high local inflation rate. On the foreign exchange market, the peso ended the trading session at ₱54.13.[49]

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.bsp.gov.ph/statistics/spei_new/tab34_inf.htm

- ↑ https://www.currency-iso.org/dam/isocy/downloads/dl_currency_iso_amendment_164.pdf

- ↑ https://www.currency-iso.org/dam/downloads/dl_currency_iso_amendment_168.pdf

- ↑ "[How-To] Type the Philippine Peso Currency Sign". Laboratory sandbox. Retrieved on 2013-10-01.

- ↑ "Overview of the BSP". Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) Official Website. Retrieved on 2013-10-01.

- ↑ "Compare currencies in South East Asia". http://aroundtheworldinaday.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Coinage of the Pre-Hispanic Era Evolution of Philippine Currency. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. Retrieved on 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Legarda, Ganzon de. (1976). Piloncitos to pesos: A brief history of coinage in the Philippines.

- ↑ 0.0476 XAU = 2,934.31 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ Puerto Rico Monetary History, welcome.topuertorico.org.

- ↑ 0.7234 XAG = 942.535 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ 0.026875 XAU = 2,933.07 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ Edwin Walter Kemmerer (2008). "V. The Fundamental Laws of the Philippine Currency reform". Modern Currency Reforms; A History and Discussion of Recent Currency Reforms in India, Porto Rico, Philippine Islands, Straits Settlements and Mexico. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4086-8800-7.

- ↑ "Republic Act No. 265". June 15, 1948. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Malaya, J. Eduardo; Jonathan E. Malaya (2004). So Help Us God: The Presidents of the Philippines and Their Inaugural Addresses. Manila: Anvil. pp. 200–214. ISBN 971-27-1486-1.

- ↑ "XE Currency Converter; XAU to PHP". Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "History of Philippine Currency - Demonetized Coin Series". Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- 1 2 Voltaire Q. Oyzon & the National Network of Normal Schools. "Commerce". 3NS Corpora Project. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "Bulan ni Balagtas". Planet Naga. 5 April 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "sentabo". Binisaya.com, English to Binisaya - Cebuano Dictionary and Thesaurus. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ Tom Marking (7 November 2005). "Cebuano Study Notes" (PDF). LearningCebuano.com. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Ester Ponce De Leon Timbancaya Elphick & Virginia Howard Sohn. "Pagsorolaten i' Cuyonon". Bisarang Cuyonon: The Official Language of Palawan. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Precy Espiritu (1984). Let's Speak Ilokano. University of Hawaii Press. p. 224. ISBN 9780824808228.

- ↑ John M. Lipski & Salvatore Santoro (2000). "Zamboangueño Creole Spanish" (PDF). Comparative Creole Syntax: 1&ndash, 40.

- ↑ Giedroyc, Richard (January 27, 2009). "Coins or Bank Notes in the Philippines?". F+W Publications, Inc. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ BSP Announces the Replacement Process of Old Banknotes (New Design Series, NDS) with New Generation Currency Banknotes Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). December 29, 2014. Retrieved on 2014-12-30.

- ↑ Poster for the demonetization of the New Design/BSP series (English) Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Poster for the demonetization of the New Design/BSP series (Filipino) Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Poster for the demonetization of the New Design/BSP series (Ilocano) Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Poster for the demonetization of the New Design/BSP series (Cebuano) Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Poster for the demonetization of the New Design/BSP series (Bicolano) Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2016-01-21.

- ↑ BSP Extends the Period for the Exchange or Replacement of New Design Series Banknotes at Par with the New Generation Currency Banknotes, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas press release, December 28, 2016

- ↑ BSP extends deadline for the exchange/replacement of old note series (NDS) at par with the new note series (NGC) until 30 June 2017 Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (www.bsp.gov.ph). Retrieved on 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "The New Generation Currency Program of the Philippines". Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. March 26, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Errors found on new peso bills". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. December 19, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Error-filled peso bills spark uproar". Philippine Daily Inquirer. December 20, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Lucas, Daxim (January 1, 2011). "The peso's makeover from an insider's view". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Philippine Money - Peso Coins and Banknotes: Error in Scientific Names on New Generation Banknotes". Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Vera, Ben O. de. "BSP releases new P100 bills". business.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ "Philippine Peso Devalued 11 To A US Dollar". New Straits Times. June 23, 1983. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ↑ "'Arrovo' bills to be replaced; firm to pay cost". Philippine Daily Inquirer. October 10, 2006. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Typo drives up peso's 'worth' - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". mobile.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Philippine Money - Peso Coins and Banknotes: Banknote Error - "Arrovo" on 100 Peso Banknote". Philippine Money - Peso Coins and Banknotes. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ Menon, Sunita (August 1, 2006). "Hey presto! A Peso's as good as a Dirham". gulfnews.com. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ GMA Public Affairs (2017-08-21), Kapuso Mo, Jessica Soho: Isang milyong piso kapalit ng 1971 piso?, retrieved 2018-07-29

- ↑ News, ABS-CBN. "'Faceless' bills due to 'rare misprint,' Bangko Sentral says". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ Philippines bank left red-faced over 'faceless' notes https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/philippines-bank-left-red-faced-over-faceless-notes-9816786

- ↑ Bangko Sentral warns against fake ₱10,000 bill http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2018/06/23/bsp-fake-ten-thousand.html

- ↑ Lucas, Daxim L. "Peso drops past P54 amid market jitters". Retrieved 2018-09-12.

Bibliography

- Banknotes and Coins June 2010, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

- Philippine Coins at the Bohol.ph website

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links

- Virtual Museum of Spanish Philippine Coinage

- Philippine Guerrilla and Emergency Notes

- Philippine Coin News & Update

- Philippine Banknotes and Coins

- American Revolutionary Coins Countermarked in Philippines