History of Philippine money

| Numismatics |

|---|

.png) |

| Currency |

| Circulating currencies |

|

| Local currencies |

|

Fictional currencies Proposed currencies |

| History |

| Historical currencies |

| Byzantine |

| Medieval currencies |

| Production |

| Exonumia |

| Notaphily |

| Scripophily |

|

The Evolution of Philippine currencies used as a medium of exchange and to make payment before the adoption of Philippine Peso coins and banknotes currently in use, included designs and forms which have been found over various period of time. For Filipino's, the gold money like Piloncitos and Barter rings are considered as the symbol of civilization. Money itself, reflected belief, culture, customs and traditions of each era and also act as a significant record in the development and history of the Philippines.

History

The Philippines is believed by some historians to be the island of Chryse, the "Golden One," which is the name given by ancient Greek writers in reference to an island rich in gold east of India. Pomponius Mela, Marinos of Tyre and the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentioned this island in 100 BC, and it is basically the equivalent to the Indian Suvarnadvipa, the "Island of Gold." Josephus calls it in Latin Aurea, and equates the island with biblical Ophir, from where the ships of Tyre and Solomon brought back gold and other trade items. The Visayan Islands, particularly Cebu had earlier encounter with the Greek traders in 21 AD.[1]

Ptolemy locates the islands of Chryse east of the Khruses Kersonenson, the "Golden Peninsula," i.e. the Malaya Peninsula. North of Chryse in the Periplus was Thin, which some consider the first European reference to China. In about the 200 BC, there arose a practice of using gold eye covers, and then, gold facial orifice covers to adorn the dead resulting in an increase of ancient gold finds. During the Qin dynasty and the Tang dynasty, China was well aware of the golden lands far to the south. The Buddhist pilgrim I-Tsing mentions Chin-Chou, "Isle of Gold" in the archipelago south of China on his way back from India. Medieval Muslims refer to the islands as the Kingdoms of Zabag and Wāḳwāḳ, rich in gold, referring, perhaps, to the eastern islands of the Malay archipelago, the location of present-day Philippines and Eastern Indonesia.[2]

The Spaniards brought their coined money when they came in 1521 and the first European coin which reaches the Philippine Islands with Ferdinand Magellan's arrival was the teston or four-reales silver coin. The teston became the de facto unit of trade between Spaniards and Filipinos before the founding of Manila in 1574. The native Tagalog name for the coin was salapi ("money").

Archaic period (c .900 AD-1521)

Piloncitos

Piloncitos were used in Kingdom of Tondo, Namayan and Rajahnate of Butuan in present-day Philippines. Piloncitos are tiny engraved bead-like gold bits unearthed in the Philippines. They are the first recognized coinage in the Philippines circulated between the 9th and 12th centuries. They emerged when increasing trade made barter inconvenient.

Piloncitos are so small—some are of the size of a corn kernel—and weigh from 0.09 to 2.65 grams of fine gold. Large Piloncitos weighing 2.65 grams approximate the weight of one mass. Piloncitos have been excavated from Mandaluyong, Bataan, the banks of the Pasig River, Batangas, Marinduque, Samar, Leyte and some areas in Mindanao. They have been found in large numbers in Indonesian archeological sites leading to questions of origin. Were Piloncitos made in the Philippines or imported? That gold was mined and worked here is evidenced by many Spanish accounts, like one in 1586 that said:

“The people of this island (Luzon) are very skillful in their handling of gold. They weigh it with the greatest skill and delicacy that have ever been seen. The first thing they teach their children is the knowledge of gold and the weights with which they weigh it, for there is no other money among them.”[3]

Barter rings

The early Filipinos also traded along with the Barter rings, which is gold ring-like ingots. These barter rings are bigger than a doughnut in size and are made of nearly pure gold.[4]

Spanish era (1521-1898)

The Spaniards brought their coined money when they came in 1521 and the first European coin which reaches the Philippine Islands with Ferdinand Magellan's arrival was the teston or four-reales silver coin. The teston became the de facto unit of trade between Spaniards and Filipinos before the founding of Manila in 1574. The native Tagalog name for the coin was salapi ("money").

Hilis Kalamay (silver cobs)

Currencies like the Alfonsino peso, Mexican cob coins (locally called hilis kalamay), other currencies and coins from other Spanish colonies were also used. Many of the coins that reached the Philippines came because of the Manila Galleon which dominated trade for the next 250 years. These were brought across the Pacific Ocean in exchange for odd-shaped silver cobs, which are also known as macuquinas. Other coins that followed were the dos mundos or pillar dollars in silver, the counterstamped coins and the portrait series, also in silver.

The Minting of Peso - Decimal coinage

An attempt to remedy the monetary confusion was made in 1848, with the introduction of the decimal system in 1857 under the second Isabelline monetary system.[5] Overseeing the conversion was Fernándo Norzagaray y Escudero, governor general in the period 1857-60.

Conversion to the decimal system with the peso fuerte (Spanish for strong peso) as the unit of account solved the accounting problem, but did little to remedy the confusion of differing circulating coinage. Renewed calls for the Philippine Islands to have a proper mint and monetary system finally came to fruition in September 1857, when Queen Isabel II authorized the creation of the Casa de Moneda de Manila and purchase of required machinery. The mint was inaugurated on March 19, 1861.

Despite the mintage of gold and silver coins, Mexican and South and Central American silver still circulated widely.

The Isabella peso or peso fuerte

.jpg)

The Isabelline peso, more formally known as the peso fuerte, was a unit of account divided into 100 céntimos (equivalent to 8 reales fuertes or 80 reales de vellón). Its introduction led to the Philippines' brief experiment with the gold standard, which would not again be attempted until the American colonial period. The peso fuerte was also a unit of exchange equivalent to 1.69 grams of gold, 0.875 fine (0.0476 XAU), equivalent to ₱1,390.87 (refers to the modern peso; as of September 2015).[6]

Coin production at the Casa de Moneda de Manila began in 1861 with gold coins (0.875 fine) of three denominations: 4 pesos, 2 pesos, and 1 peso. On March 5, 1862, Isabel II granted the mint permission to produce silver fractional coinage (0.900 fine) in denominations of 10, 20, and 50 centimos de peso. Minting of these coins started in 1864, with designs similar to the Spanish silver escudo.

The Alfonso peso, the Spanish-Filipino peso

The currency in the Philippines was standardized by the Spanish government with the minting of a silver peso expressly for use in the colony and firmly reestablishing the silver standard as the Philippine monetary system. The coin, which was to be later known as the Spanish-Filipino peso, was minted in Madrid in 1897 and bore the bust of King Alfonso XIII. The specifications of the coin was 25 grams of silver .900 fine. This configuration was also used in the creation of the Puerto Rican provincial peso in 1895 giving both coins the equivalency of 5 pesetas.[7]

The new monetary standard finally established the peso as 25 grams silver, 0.900 fine (0.7234 XAG), equivalent to ₱942.535 modern pesos of as of 22 December 2010.[8]

The Spanish-Filipino peso remained in circulation and were legal tender in the islands until 1904, when the American authorities demonetized them in favor of the new US-Philippine peso.

Sulu coins

The Sultanate of Sulu in the southernmost islands engaged actively in barter trade with the Arabs, Chinese, Bornean, Moluccan, and British traders. The Sultans issued coins of their own as early as the 5th century. Coins of Sultan Azimud Din that exist today are of base metal Tin, Silver and alloy bearing Arabic inscriptions and dated 1148 AH corresponding to the year 1735 in the Christian era.

First Philippine Republic (Revolutionary period 1898-1901)

Asserting its independence after the Philippine Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898, the República Filipina (Philippine Republic) under General Emilio Aguinaldo issued its own coins and paper currency backed by the country’s natural resources. The coins were the first to use the name centavo for the subdivision of the peso. The island of Panay also issued revolutionary coinage. After Aguinaldo's capture by American forces in Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901, the revolutionary peso ceased to exist.

American colonial Period (1901-1945)

_50_Centavos_Silver_Coin_1918_(s).jpg)

After the United States took control of the Philippines, the United States Congress passed the Philippine Coinage Act of 1903, established the unit of currency to be a theoretical gold peso (not coined) consisting of 12.9 grains of gold 0.900 fine (0.026875 XAU), equivalent to ₱2,933.07 modern pesos of as of 22 December 2010.[9] This unit was equivalent to exactly half the value of a U.S. dollar [10] and maintained its purchasing power until the opening day of the Central Bank of the Philippines in 1949.

The act provided for the coinage and issuance of Philippine silver pesos substantially of the weight and fineness as the Mexican peso, which should be of the value of 50 cents gold and redeemable in gold at the insular treasury, and which was intended to be the sole circulating medium among the people. The act also provided for the coinage of subsidiary and minor coins and for the issuance of silver certificates in denominations of not less than 2 nor more than 10 pesos.

It also provided for the creation of a gold-standard fund to maintain the parity of the coins so authorized to be issued and authorized the insular government to issue temporary certificates of indebtedness bearing interest at a rate not to exceed 4 per cent per annum, payable not more than one year from date of issue, to an amount which should not at any one time exceed 10 million dollars or 20 million pesos.

Commonwealth Period (1935-1946)

When Philippines became a US Commonwealth in 1935, the coat of arms of the Philippine Commonwealth were adopted and replaced the arms of the US Territories on the reverse of coins while the obverse remained unchanged. This seal is composed of a much smaller eagle with its wings pointed up, perched over a shield with peaked corners, above a scroll reading "Commonwealth of the Philippines". It is a much busier pattern, and widely considered less attractive.

The "Mickey Mouse money" (Fiat peso)

-500_Pesos_(1944).jpg)

.

During World War II in the Philippines, the occupying Japanese government-issued fiat currency in several denominations; this is known as the Japanese government-issued Philippine fiat peso (see also Japanese invasion money). The Second Philippine Republic under José P. Laurel outlawed possession of guerrilla currency, and declared a monopoly on the issuance of money, so that anyone found to possess guerrilla notes could be arrested. Some Filipinos called the fiat peso "Mickey Mouse money". Many survivors of the war tell stories of going to the market laden with suitcases or "bayóng" (native bags made of woven coconut or buri leaf strips) overflowing with the Japanese-issued bills. According to one witness, 75 "Mickey Mouse" pesos, or about 35 U.S. dollars at that time, could buy one duck egg.[11] In 1944, a box of matches cost more than 100 Mickey Mouse pesos.[12]

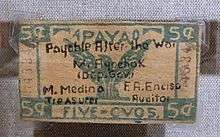

"Guerilla Pesos" (Emergency circulating notes)

The Emergency circulating notes were currency printed by the Philippine Commonwealth Government in exile during World War II. These "guerrilla pesos" were printed by local government units and banks using crude inks and materials. Due to the inferior quality of these bills, they were easily mutilated. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic under President José P. Laurel outlawed possession of guerrilla currency and declared a monopoly on the issuance of money and anyone found to possess guerrilla notes could be arrested or even executed.

Modern currencies (1946-present)

English Series

.jpg)

The English Series were Philippine banknotes that circulated from 1951 to 1971. It was the only banknote series of the Philippine peso to use English as the language.

Pilipino series

The Pilipino series banknotes is the name used to refer to Philippine banknotes issued by the Central Bank of the Philippines from 1969 to 1973, during the term of President Ferdinand Marcos. It was succeeded by the Ang Bagong Lipunan Series of banknotes, to which it shared a similar design. The lowest denomination of the series is 1-piso and the highest is 100-piso. This series represented a radical change from the English series. The bills underwent Filipinization and a design change.After the declaration of Proclamation № 1081 on September 23, 1972, the Central Bank demonetized the existing banknotes (both the English and Pilipino series) on March 1, 1974, pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 378.[13] All the unissued banknotes were sent back to the De La Rue plant in London for overprinting the watermark area with the words "ANG BAGONG LIPUNAN" and an oval geometric safety design.

Ang Bagong Lipunan series

The Ang Bagong Lipunan Series (literally, ”The New Society Series") is the name used to refer to Philippine banknotes issued by the Central Bank of the Philippines from 1973 to 1985. It was succeeded by the New Design series of banknotes. The lowest denomination of the series is 2-piso and the highest is 100-piso. After the declaration of Proclamation № 1081 by President Ferdinand Marcos on September 23, 1972, the Central Bank was to demonetize the existing banknotes in 1974, pursuant to Presidential Decree 378. All the unissued Pilipino Series banknotes (except the one peso banknote) were sent back to the De La Rue plant in London for overprinting the watermark area with the words "ANG BAGONG LIPUNAN" and an oval geometric safety design. The one peso note was replaced with the two peso note, which features the same elements of the demonetized "Pilipino" series one peso note. On September 7, 1978, the Security Printing Plant in Quezon City was inaugurated to produce the banknotes. And a minor change of its BSP seal.

New Design Series

The New Design Series (NDS) was the name used to refer to Philippine banknotes issued from 1985 to 1993; it was renamed the BSP series when the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas was established in 1993. It was succeeded by the New Generation Currency (NGC) banknotes issued on December 16, 2010. The NDS/BSP banknotes were no longer in print and legal tender after December 31, 2015.

The NDS/BSP notes will be demonetized and exchanged with NGC notes within 2016; all will be withdrawn from circulation originally scheduled by January 1, 2017.[14] The demonetization was however extended until April 1, 2017 after the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas approved the extension due to public clamor.[15]

New Generation Currency (current)

.jpg)

In 2009, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) announced that it has launched a massive redesign for current banknotes and coins to further enhance security features and improve durability.[16] The members of the numismatic committee include BSP Deputy Governor Diwa Guinigundo and Ambeth Ocampo, Chairman of the National Historical Institute. The new banknote designs feature famous Filipinos and iconic natural wonders. Philippine national symbols will be depicted on coins. The BSP started releasing the initial batch of new banknotes in December 2010.

References

- ↑ Cebu, a Port City in Prehistoric and in Present Times. Retrieved September 05, 2008, citing Regalado & Franco 1973, p. 78

- ↑ Zabag. Retrieved September 02, 2008.

- ↑ http://opinion.inquirer.net/10991/%E2%80%98piloncitos%E2%80%99-and-the-%E2%80%98philippine-golden-age%E2%80%99

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.ph/permanenttraveling.php?page=classicalgoldwork

- ↑ Legarda, Ganzon de. (1976). Piloncitos to pesos: A brief history of coinage in the Philippines.

- ↑ 0.0476 XAU = 2,934.31 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ Puerto Rico Monetary History, welcome.topuertorico.org.

- ↑ 0.7234 XAG = 942.535 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ 0.026875 XAU = 2,933.07 PHP, xe.com.

- ↑ Edwin Walter Kemmerer (2008). "V. The Fundamental Laws of the Philippine Currency reform". Modern Currency Reforms; A History and Discussion of Recent Currency Reforms in India, Porto Rico, Philippine Islands, Straits Settlements and Mexico. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4086-8800-7.

- ↑ Barbara A. Noe (August 7, 2005). "A Return to Wartime Philippines". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ↑ Agoncillo, Teodoro A. & Guerrero, Milagros C., History of the Filipino People, 1986, R.P. Garcia Publishing Company, Quezon City, Philippines

- ↑ Presidential Decree 378, Chan Robles Virtual Law Library

- ↑ "Still hanging on to your old peso bills? Read this". ABS-CBNnews.com. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ BSP Extends the Period for the Exchange or Replacement of New Design Series Banknotes at Par with the New Generation Currency Banknotes, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas press release, December 28, 2016

- ↑ "The New Generation Currency Program of the Philippines". Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. March 26, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

Bibliography

- Banknotes and Coins June 2010, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

- Philippine Coins at the Bohol.ph website

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links

- Virtual Museum of Spanish Philippine Coinage

- Philippine Guerrilla and Emergency Notes

- Philippine Coin News & Update

- Philippine Banknotes and Coins