Pensionado Act

| Pensionado Act | |

|---|---|

| Philippine Commission | |

| Philippine Commission's Act 854 | |

| Enacted by | Insular Government of the Philippine Islands |

| Date passed | 26 August 1903 |

| Introduced by | Bernard Moses |

| Summary | |

| Provide for education of select Filipinos to receive education in the United States | |

| Status: Expired | |

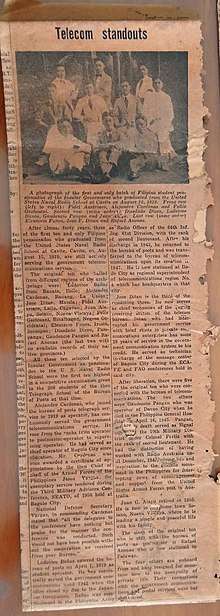

The Pensionado Act is Act Number 854 of the Philippine Commission.[1] Passed by Congress,[2] it established a scholarship program for Filipinos to attend school in the United States. It was the largest American scholarship program until the Fulbright Program was established in 1948.[3] Students of this scholarship program were known as pensionados.[4]

From the initial 100 students, the program provided education in the United States to around 14,000.[5] The alumni of the program went on to work for the government in the Philippine Islands;[6] they would go on to play important roles in the education of their fellow Filipinos, and be influential members of the Philippine society.[5] Due to their success, other immigrants from the Philippines followed, settling in the United States.[7] In 1943, the program ended.[8]

During World War II, Japan initiated a similar program during its occupation of the Philippines.[9] Following the War, and Philippine independence, Filipino students continued to come to the United States utilizing government scholarships.[3]

Background

During the Spanish era of the Philippines, education other than that provided by religious institutions, was not generally available to the average Filipino until after 1863.[10] Following the Spanish–American War in the late 19th century, Filipinos became nationals of the United States.[11] At the behest of American Soldiers, well-to-do families began to send their children to the United States for education; one example was Ramon Jose Lascon, who went on to earn his Ph.D. at Georgetown University at the age of 20.[12] This followed a trend of well-to-do families sending students to the United States, with Chinese students first coming to the United States beginning in 1847, and Japanese students coming to the United States beginning in 1866.[13]

The first school established by the United States in the Philippines was on Corregidor, and in March 1900 the Philippine Commission began to pass legislation to provide for public education, including secondary education in each provincial capital beginning in 1902. However, there were a lack of educators, with many Soldiers taking up the task of becoming teachers. This problem was first addressed by the Thomasites arrival in 1901; these teachers from the United States were also tasked to train Filipinos to become teachers, however schools continued to have a shortage of educators.[14]

Directed by then-Governor General William Howard Taft, more was to be done to foster goodwill between Filipinos and Americans;[15] In 26 August 1903, Act 854 was passed.[12] Initially envisioned by Professor Bernard Moses in July 1900, the program was to pacify Filipino opposition following the Philippine–American War, as well as prepare the islands for self-governance, by showing the difference between Spain and the United States through direct exposure.[12] Additionally, the program was to expose the United States to "the best and brightest Filipino youths" to "make a favorable impression" of the Philippines in the United States.[16]

Enactment

The program was initially overseen by David Prescott Barrows, the Philippines' director of education at the time.[17] In its first year, there were twenty thousand applicants, of which a hundred were selected.[5] These early pensionados were chosen from the wealthy and elite class of Filipinos.[18][19] Prior to taking college courses, the initial pensionados attended high school in the continental United States for the purpose of language and culture acclimation.[20] In some areas of the United States, the pensionados were some of the first Filipinos to immigrate to those areas.[21] As much as a quarter of the initial batch of pensionados went to school in the Chicago region.[22]

During the second year of the program, the first Pinay pensionados were chosen; however the number of Filipinas chosen for the program created a gender imbalance favoring Pinoy pensionados.[23] As the program continued, the number of pensionados steadily increased, with there being 180 pensionados in 1907, and 209 in 1912.[24] Among the pensionados were some of the first Filipino nursing students to come to the United States.[25] There was a pause in the program between 1915 and 1917.[26] In 1921, the Philippine government had allotted ₱472,000 of their budget for supporting 111 pensionados, 13 of whom were working on achieving a doctoral degree.[27]

Schools attended

Pensionados went on to attend many colleges and universities, including the following:

- California Christian College[28]

- Columbia University[5]

- Cornell University[29]

- Drexel Institute[30]

- Harvard University[5]

- Indiana University[30]

- Los Angeles Junior College[28]

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology[30]

- Oberlin College[30]

- San Diego Normal School[31]

- Stanford University[5]

- Syracuse University[28]

- State Normal School[20]

- University of California[5]

- University of Chicago[20]

- University of Illinois[5]

- University of Michigan[30]

- University of Southern California[32]

- University of Washington[29]

- Woodbury College[28]

Impact

From 1903, until 1938, pensionados studied in the United States, with the majority returning to the Philippines.[33] These former students would go on to serve within the government established in the islands by the United States;[6] this was a scholarship requirement, and had to be at least 18 months of government service.[34] Before returning to the Philippines, pensionados began student-run newspapers, which were part of the beginning of media geared specifically to the Filipino diaspora in the United States.[35]

Known as "fountain pen boys", by 1920 nearly five thousand pensionados had attended American schools, receiving post-secondary education.[36] In 1922 alone, there were almost 900 Filipinos attending college in the United States.[37] Due to the Great Depression funding for the program was reduced.[38] By 1938, around fourteen thousand pensionados had received their education in the United States, some going onto important positions upon returning to the Philippines.[5][39] In 1943, the program ended.[40] Near the end of World War II, the Commonwealth Government in Exile was offered to have some of the pensionados trained in foreign relations, anticipating the 1946 independence of the Philippines from the United States.[41]

Upon returning to the Philippines, they were often called "American boys" and faced discrimination by other Filipinos.[42] This discrimination was due to the view that the returning pensionados "legitimated U.S. colonial rule in the Philippines".[43] This negative reception of the pensionados was not limited to the Philippines, but was shared by some of the later Filipino immigrants to the United States who were not the children of the well-to-do in the Philippines, as shown in the writings of Carlos Bulosan.[44] Some of the returning pensionados would go on to help the development of Filipino nationalism.[45]

A majority of the returning pensionados were assigned as educators, with some later becoming superintendents.[14] For instance University of Michigan alum Esteba Adaba, became the director of education for the Philippines under the Roxas Administration;[46] he would go on to become a Philippine senator.[47] Another pensionado Jorge Bocobo, a University of Indiana alum, went on to become a President of the University of the Philippines.[48][49] For those pensionados who studied nursing, they would establish nursing schools, whose students would go on to immigrate around the world to fill nursing shortages.[50] Others went on to be successful in fields outside of education, and would move on to become part of the "governing elite".[51] Examples of these pensionados include Secretary of Finance Antonio de las Alas,[51] Senator Camilo Osias,[51][52] Major General Carlos P. Romulo,[48] writer Bienvenido Santos,[48] and Chief Justice José Abad Santos.[48] When architects began to be registered in the Philippines in 1921, a pensionado was the second to be registered.[53]

Other students

Due to the success of the returning pensionados, it enticed others to immigrate to the United States, including non-pensionados who self-financed their attempt to receive higher education, including some veterans of the United States Navy.[54] By the 1920s, these self-financed students outnumbered the pensionados.[55] The aspiration of education advancement became a dominant theme for those Filipinos coming to the United States.[56] So many Filipinos would seek to advance their education that in 1930, they were the third largest population of students from outside of the continental United States, only surpassed by Chinese and Canadian students;[57] some of those Chinese students were attending using a similar government funding method known as the Boxer Indemnity.[58]

Some of these students would go on to fund their education as domestic workers, with some attending Chapman College and the University of Southern California, with a few earning graduate degrees;[28] Others attempted to fund their education by working as farmworkers;[59] one of these immigrants who were part of this group of students was Philip Vera Cruz.[36] Many of these self-funding students would not return to the Philippines, settling in the United States;[7][60] one example is Llamas Rosario, who earned graduate degrees from Columbia University and New York University, and went on to found the Filipino Pioneer, a newspaper published in Stockton, California.[61] Along with those who immigrated to the United States without educational aspirations, these Filipinos started the second wave of immigration to the United States.[62] Those who remained, who had completed their education, found that they would not be hired in their trained industries due to racial discrimination.[63] In additional, laws barred Filipinos from professional employment, such as the ones in California.[64]

Similar programs

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the Japanese government also sponsored students to study in Japan, with two groups being sent Japan in 1943 and 1944.[65] The program was administrated out of the former American School in Japan by a part of the Ministry of Greater East Asia.[9] Prior to departing for Japan, the students were disciplined by the Second Republic Constabulary to cleanse their thinking of anti-Japanese sentiments;[66] this was conducted at Malacañang, but only after the students had passed individual interviews with a panel of Japanese officials which included General Wachi.[9] In total there were a total of 51 students who studied in Japan under the program, referred to as "Nantoku" ナントク.[67]

After the Philippines became an independent nation thousands more Filipinos came to the United States for education utilizing the Fulbright Program.[68] The Fulbright exchanges have since become a larger program than the "pensionado" program.[3] A similar, but smaller program to fund education of Filipinos in the United States was done under the Smith–Mundt Act, which was specific for civic leaders.[69]

Inspired legislation

In the early 21st century other legislating sharing the name of the act, were introduced in the Senate of the Philippines. In 2010, Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago submitted the "Pensionado Act of 2010", which remained in committee.[70] In 2017, Senator Sonny Angara submitted "Pensionado Act of 2017" which is in committee of the current Philippine Senate.[71]

See also

References

- ↑ United States. Congress (1912). Congressional edition. U.S. G.P.O. p. 167.

- ↑ Essie E. Lee (2000). Nurturing Success: Successful Women of Color and Their Daughters. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-275-96033-9.

Willie V. Byran (2007). Multicultural Aspects of Disabilities: A Guide to Understanding and Assisting Minorities in the Rehabilitatiion Process. Charles C Thomas Publisher. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-398-08509-4. - 1 2 3 Hazel M. McFerson (2002). Mixed Blessing: The Impact of the American Colonial Experience on Politics and Society in the Philippines. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-313-30791-1.

- ↑ "Pensionados". A Century of Challenge and Change: The Filipino American Story. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program. 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shelley Sang-Hee Lee (1 October 2013). A New History of Asian America. Routledge. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-135-07106-6.

- 1 2 Knake, J. Matthew (Spring 2014). "Education Means Liberty: Filipino Students, Pensionados and U.S. Colonial Education" (PDF). Western Illinois Historical Review. 6. ISSN 2153-1714.

- 1 2 Melendy, H. Betty (November 1974). "Filipinos in the United States". Pacific Historical Review. 43 (4): 520–547. doi:10.2307/3638431. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Mary Yu Danico (19 August 2014). Asian American Society: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 681. ISBN 978-1-4833-6560-2.

- 1 2 3 Goodman, Grant K. (August 1962). An Experiment in Wartime Intercultural Relations: Philippine Students in Japan, 1942-1945 (PDF). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University.

- ↑ Dacumos, Rory (August 2015). Philippine Colonial Education System (Report). researchgate. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

Hardacker, Erin P. (Winter 2012). "The Impact of Spain's 1863 Educational Decree on the Spread of Philippine Public Schools and Language Acquisition". European Education. 44 (4): 8–30. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

"Did You Know: Educational Decree of 1863". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2018. - ↑ "The Filipino Diaspora in the United States" (PDF). Rockefeller-Aspen Diaspora Program. Migration Policy Institute. February 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014. Lay summary (21 October 2014).

- 1 2 3 Francisco, Adrianne Marie (Summer 2015). From Subjects to Citizens: American Colonial Education and Philippine Nation-Making, 1900-1934 (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Baylon Sorenson, Krista (22 April 2011). Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940 (Honors Program). Butler University. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- 1 2 Casambre, Napoleon J. (1982). "The Impact of American Education in the Philippines" (PDF). Educational Perspectives. 21 (4): 7–14. Retrieved 4 August 2018 – via University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- ↑ John W. Collins; Nancy Patricia O'Brien (31 July 2011). The Greenwood Dictionary of Education: Second Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-313-37930-7.

- ↑ Paul A. Kramer (13 December 2006). The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-8078-7717-3.

- ↑ Reyes, Bobby M. (5 April 2011). "From Bulusan to Bulosan: Reviving the "Pensionado" Tradition". Mabuhay Radio. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Elliott Robert Barkan (1 January 1999). A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook on America's Multicultural Heritage. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 203–204. ISBN 978-0-313-29961-2.

- ↑ "Filipino Migration to the United States". The Philippine History Site. University of Hawaii at Manoa. 2001. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Yoon K. Pak; Dina C. Maramba; Xavier J. Hernandez (25 March 2014). Asian Americans in Higher Education: Charting New Realities: AEHE Volume 40, Number 1. Wiley. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-118-88500-0.

- ↑ Elnora Kelly Tayag (2011). Filipinos in Ventura County. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-7473-8.

- ↑ John P. Koval; Larry Bennett; Michael Bennett (2006). The New Chicago: A Social and Cultural Analysis. Temple University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-59213-772-5.

- ↑ Nancy Foner; Ruben G. Rumbaut; Steven J. Gold (16 November 2000). Immigration Research for a New Century: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Russell Sage Foundation. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-61044-829-1.

- ↑ Jonathan H. X. Lee (16 January 2015). History of Asian Americans: Exploring Diverse Roots: Exploring Diverse Roots. ABC-CLIO. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-313-38459-2.

- ↑ Wayne, Gil (26 May 2015). "History of Nursing in the Philippines". Nurses Labs. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

Yves Boquet (19 April 2017). The Philippine Archipelago. Springer. p. 391. ISBN 978-3-319-51926-5. - ↑ Lan Dong (14 March 2016). Asian American Culture: From Anime to Tiger Moms [2 volumes]: From Anime to Tiger Moms. ABC-CLIO. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4408-2921-5.

- ↑ Philippines. Gobernador-General; Philippines. Governor (1922). Report of the Governor General of the Philippine Islands to the Secretary of War. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Linda España-Maram (25 April 2006). Creating Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila: Working-Class Filipinos and Popular Culture, 1920s-1950s. Columbia University Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0-231-51080-6.

- 1 2 Jon Sterngass (2007). Filipino Americans. Infobase Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Victor Román Mendoza (11 November 2015). Metroimperial Intimacies: Fantasy, Racial-Sexual Governance, and the Philippines in U.S. Imperialism, 1899-1913. Duke University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-8223-7486-2.

- ↑ Judy Patacsil; Rudy Guevarra, Jr.; Felix Tuyay (2010). Filipinos in San Diego. Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7385-8001-2.

- ↑ Office of Historical Resources (April 2018). Los Angeles Citywide Historical Context Statement; Context: (PDF) (Report). City of Los Angeles. p. 12. SurveyLA. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Joe Alan Austin; Michael Willard (June 1998). Generations of Youth: Youth Cultures and History in Twentieth-Century America. NYU Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8147-0645-9.

- ↑ Dennis O. Flynn; Arturo Giráldez; James Sobredo (18 January 2018). "The 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act and Filipino Exclusion: Social, Political and Economic Context Revisited". Studies in Pacific History: Economics, Politics, and Migration. Taylor & Francis. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-351-74248-1.

- ↑ Regis, Marie P. (Fall 2013). Mediating!Global!Filipinos:!The!Filipino!Channel!and!the!Filipino!Diaspora (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 Craig Scharlin; Lilia V Villanueva (2000). Philip Vera Cruz: A Personal History of Filipino Immigrants and the Farmworkers Movement. University of Washington Press. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-0-295-80295-4.

- ↑ United States. Bureau of Insular Affairs (1922). Directory of Filipino Students in the United States.

- ↑ Regis, Ethel Marie P. (Fall 2013). Mediating Global Filipinos: The Filipino Channel and the Filipino Diaspora (PDF) (Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Robert M. Jiobu. Ethnicity and Assimilation: Blacks, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Japanese, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Whites. SUNY Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4384-0790-6.

Uma Anand Segal (2002). A Framework for Immigration: Asians in the United States. Columbia University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-231-12082-1. - ↑ James Ciment; John Radzilowski (17 March 2015). American Immigration: An Encyclopedia of Political, Social, and Cultural Change: An Encyclopedia of Political, Social, and Cultural Change. Taylor & Francis. p. 2832. ISBN 978-1-317-47716-7.

- ↑ Hull, Cordell (24 March 1944). "The Secretary of State to the Philippine Resident Commissioner to the United States (Elizalde)" (PDF) (Letter). Letter to Joaquín Miguel Elizalde. Retrieved 1 September 2018 – via University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ Dina C. Maramba; Rick Bonus (1 December 2012). The 'Other' Students: Filipino Americans, Education, and Power. IAP. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-62396-075-9.

- ↑ Lan Dong Ph.D. (14 March 2016). Asian American Culture: From Anime to Tiger Moms [2 volumes]: From Anime to Tiger Moms. ABC-CLIO. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-4408-2921-5.

- ↑ Kent A. Ono (15 April 2008). A Companion to Asian American Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-4051-3709-6.

- ↑ Manalansan IV, Martin F.; Espiritu, Agusto F. "The Field" (PDF). NYU Press.

- ↑ The Michigan Alumnus. UM Libraries. 1946. p. 318. UOM:39015071120854.

- ↑ "Esteban Abada". Senate of the Philippines. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 John D. Buenker; Lorman A. Ratner; Lorman Ratner (2005). Multiculturalism in the United States: A Comparative Guide to Acculturation and Ethnicity. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-313-32404-8.

- ↑ Medina, Marielle (19 October 2016). "DID YOU KNOW: Jorge Bocobo". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippines. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Rodis, Rodel (12 May 2013). "Why are there so many Filipino nurses in the US?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

Varona, Rae Ann (2 May 2018). "Honoring the inspiration of Fil-Am nurses this National Nurses Week". Asian Journal. Retrieved 30 August 2018. - 1 2 3 Lambino, John X. (August 2015). "Political-Security, Economy, and Culture within the Dynamics of Geopolitics and Migration: On Philippine Territory and the Filipino People" (PDF). Research Project Center. Kyoto University. 15 (4). Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "Oasis, Camilo". History, Art & Archives. United States House of Representative. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Alcazaren, Paulo (7 September 2002). "Philippine architecture in the 1950s". Philippine Star. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Estella Habal (28 June 2007). San Francisco's International Hotel: Mobilizing the Filipino American Community in the Anti-Eviction Movement. Temple University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-59213-447-2.

- ↑ Cecilia M. Tsu (18 July 2013). Garden of the World: Asian Immigrants and the Making of Agriculture in California's Santa Clara Valley. Oxford University Press USA. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-973477-1.

Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian Skoggard (30 November 2004). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9. - ↑ Posadas, Barbara M.; Guyotte, Roland L. (Summer 1992). "Aspiration and Reality: Occupational and Educational Choice among Filipino Migrants to Chicago, 1900-1935". Illinois Historical Journal. 85 (2): 89–104. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Franklin Ng (23 June 2014). Asian American Family Life and Community. Taylor & Francis. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-136-80122-8.

- ↑ Madeline Y. Hsu (27 April 2015). The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority. Princeton University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4008-6637-3.

R. Garlitz; L. Jarvinen (6 August 2012). Teaching America to the World and the World to America: Education and Foreign Relations since 1870. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-137-06015-0. - ↑ Calaustro, Edna (21 May 1992). "Filipino Immigration to the U.S." Synapse. University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Murray, Vince; Solliday, Scott. The Filipino American Community (PDF) (Report). City of Phoenix. Asian American Historic Property Survey. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ "ROSARIO, E. Llamas "Bert"". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. 3 January 2002. Retrieved 4 August 2018 – via SFGate.

Vengua, Jean (Fall 2010). Migrant Scribes and Poet-Advocates: U.S. Filipino Literary History in West Coast Periodicals, 1905 to 1941 (PDF) (Doctor of Philosophy dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 4 August 2018. - ↑ Fern L. Johnson (2000). Speaking Culturally: Language Diversity in the United States. SAGE. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8039-5912-5.

2005 Congressional Record, Vol. 151, Page S13593 (14 December 2005) - ↑ Perez, Frank Ramos; Perez, Leatrice Bantillo (Winter 1994). "Filipinos in San Joaquin County" (PDF). The San Joaquin Historian. VIII (4): 3–19. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Estrella Piring, Jr., Donald (Fall 2016). Kain Na! The Life and Times of Calros Bulosan (PDF) (Masters Thesis). California State University, Sacramento. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

Castillo, Adelaida (Summer 1976). Moss, James E, ed. "Filipino Migrants in San Diego 1900-1946". 22 (3). Retrieved 25 August 2018. - ↑ Saniel, Josefa M. (16 February 1991). The Study of Japan in the Philippines: Focus on the University of the Philippines (PDF). Kyoto, Japan: International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- ↑ M.c. Halili (2004). Philippine History. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 232. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ↑ "An Abridged Historical Commentary on the ASEAN Council of Japan Alumni (ASCOJA)". Philippines-Japan Society, Inc. 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

Ken'ichi Goto (2003). Tensions of Empire: Japan and Southeast Asia in the Colonial and Postcolonial World. NUS Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-9971-69-281-0. - ↑ Artemio R. Guillermo (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-8108-7246-2.

- ↑ Lay, James S. (5 April 1954). "No. 359 Memorandum by the Executive Secretary (Lay) to the National Security Council". Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Sicat, Gerardo P. (28 March 2018). "A dream of foreign education fulfilled". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 1 September 2018. - ↑ "Pensionado Act of 2010". Senate Bill No. 2498. Senate of the Philippines. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "Pensionado Act of 2017". Senate Bill No. 1343. Senate of the Philippines. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

Further reading

- A.M. Jose S. Reyes (1923). :Legislative History of America's Economic Policy Toward the Philippines.

- Kenneth White Munden (1943). Los Pensionados: The Story of the Education of Philippine Government Students in the United States 1903-1943. National Archives.

- Teodoro, Noel V. (1 March 1999). "Pensionados and Workers: The Filipinos in the United States, 1903–1956". Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 8 (1): 157–178. doi:10.1177/011719689900800109.

- Filipino Students' Federation of America (1920). Philippine Herald.

External links

- Orosa, Mario E. "The Philippine Pensionado Story" (PDF). Orosa Family Web Site.

- Paguio, Divine. "Pensionadas". Asian Pacific American Women. Tumblr.

- "Today's Estudyante and the Legacy of Pensionados". Bakitwhy. Kasama Media, LLC. 9 December 2008.