Otto Hersing

| Otto Hersing | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) |

Zerstörer von Schlachtschiffe (Destroyer of warships)[1] Retter der Dardanellen (Saviour of the Dardanelles)[2] |

| Born |

30 November 1885 Mulhouse, once German Empire |

| Died |

5 July 1960 (aged 74) Angelmodde near Münster, Germany |

| Buried | Angelmodde |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1903–1918, 1919–24 |

| Rank | Korvettenkapitän |

| Commands held | U-21 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Pour le MériteIron Cross 1st and 2nd ClassAlbert Order (Saxony)Iron Crescent (Ottoman Empire) |

Otto Hersing (30 November 1885 – 1 July 1960) was a German naval officer who served as U-boat commander in the Kaiserliche Marine and the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine during World War I.

In September 1914, while in command of the German U-21 submarine, he became famous for the first sinking of an enemy ship by a self-propelled locomotive torpedo.

Career

Early Life and training

Hersing joined the Imperial German Navy on 1903.[3] He received his first training on the Stosch school ship, on the Blücher corvette and on the artillery training ship Mars. He served as a Fähnrich on the battleship Kaiser Wilhelm II. On September 1906 he was promoted to Leutnant and transferred on the light cruiser Hamburg. On 1909 he was promoted to Oberleutnant. From 1911 to 1913 Hersing served as watch officer on the protected cruiser Hertha and he had the chance to sail around the Mediterranean Sea and the West Indies.

World War I and North Sea operations

In 1914 Hersing was promoted to Kapitänleutnant and received a special training for the submarine warfare. When the World War I broke out he was given command of the U-21, at the time located in the island of Heligoland, on the North Sea. Between August and September the U-21 carried out some reconnaissance actions in the North Sea, but he wasn't able to find out any Entente ships. Hersing then tried to force with his unit the Firth of Forth, at that time a British naval base, but with no success.[4]

On September 5 the German commander spotted the light cruiser Pathfinder off the Scottish coast, that was sailing at a reduced speed of 5 knots due to a short supply of coal. Hersing decided to attack the ship and hit her with a single torpedo just below the conning tower, close to the ship's powder magazine, which was destroyed by a great explosion. The ship sank in a short time and 261 sailors were killed in the action.[5][6] It was the first sinking of a modern military ship by a submarine armed with torpedoes.[7][8]

On 14 November the U-21 intercepted the French steamer Malachite; Hersing ordered the crew to abandon the ship before he sank the enemy vessel with his deck gun. Three days later the British collier SS Primo had the same fate.[9] These two ships were the first vessels to be sunk in the restricted German submarine offensive against British and French merchant shipping.[10]

At the beginning of 1915 Hersing received the Iron Cross 2nd Class,[11] and was ordered to extend German submarine warfare to the western coast of the British isles. On 21 January he sailed from Wilhelmshaven and entered the Irish Sea, where he tried to shell the aifield on the Walney Island but had no success.[12] On 30 January the U-21 met and sunk three allied merchants, the SS Ben Cruachan, the SS Linda Blanche[13] and the SS Kilcuan. In every case, Hersing respected the prize rules helping the crew of the intercepted ships. He then withdrew his unit to Germany and at the beginning of February cruised back to the friendly port of Wilhelmshaven, after passing back through the Dover Barrage without consequences for the second time in a short while.

Operations in the Mediterranean and the Dardanelles

Hersing was ordered in April to transfer in the Mediterranean Sea to support the Ottoman Empire, allied to Germany and under attack of British and French troops at the Dardanelles. He sailed with his U-21 from Kiel on 25 April, and arrived to the Austro-Hungarian port of Cattaro after eighteen days of voyage.[14] Due to a problem in refueling, Hersing was forced to slow down the speed of his submarine and to proceed on the surface, exposing it to the risk of being detected by allied units.[15]

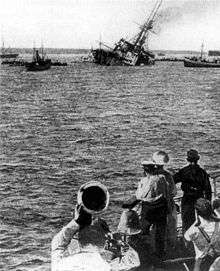

After a week spent in the friendly port, Hersing reached the new operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May. The same first day he spotted out the British battleship HMS Triumph. The German commander brought his U-boat to within 300 yards (270 m) of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit and sunk the battleship, causing the death of 3 officers and 75 members of the crew.[16] After the action the Kapitänleutnant took his submarine on the depth and awaited there for 28 hours before re-emerging to recharge the electric batteries. On 27 May the U-21 sunk her second Allied battleship in the Dardanelles, the HMS Majestic. Hersing was able to avoid the escorting fleet and the torpedo nets that surrounded the ship, and the Majestic sunk within four minutes[17] off of Cape Helles, causing the death of at least 40 members of the crew[18] (many of them were trapped in the same defensive nets that were supposed to protect the ship[19]). Hersing's successes forced the Allied to withdraw all the ships from Cape Helles, and Great Britain offered a 100,000 pound reward for the capture of the German commander.[20] On 5 June he received the Pour le Mérite, the highest German military honor,[19][21] as a prize for his war actions in the Mediterranean. In the same year 1915 he gained the honorary citizenship of the German town of Bad Kreuznach,[22] and he started to be nicknamed Zerstörer von Schlachtschiffe (destroyer of warships).[6]

All the U-21 crew spent then a month in Constantinople because of the repairs needed by their submarine. In the Ottoman capital they were tributed as heroes and received a great welcome. Once the work was finished, U-21 sortied through the Dardanelles for another patrol. Hersing then found the Allied munitions ship Carthage, and sunk her with a single torpedo on 4 July.[23] Right after that the german submarine was forced to return to Constantinople after bumping an anti-submarine mine that did not cause serious damage.[24] The unit made then a brief service in the Black Sea, but with no results.[25] The ship returned then to the Mediterranean, where in September she found out that the Allies had established a complete blockade of the Dardanelles, using mines and nets in order to prevent enemy submarines to operate in that area.

Hersing returned then to Cattaro [26] and received the order to help the Austro-Hungarian navy in her fight against the Italian navy. The U-21 and all her crew was then commissioned into the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine, and took the name of U-36.[27] This expedient was necessary to allow the submarine to operate against the Italian merchant fleet; in fact Germany was not yet legally at war with the Kingdom of Italy. The unit served under this name until Italy declared war on Germany on 27 August 1916. In February Hersing first sank the British steamer SS Belle of France,[28] then the French armored cruiser Amiral Charner, intercepted off the Syrian coast. This last operation caused the death of 427 crew members.[29] Between April and October 1916 the U-36 caused a lot of troubles to the Allied naval units in the Mediterranean, and sank numerous merchant ships including the British steamer SS City of Lucknow (3,677 tons, sunk near Malta on April 30[30]), three small Italian ships (intercepted near Corsica between October 26 and 28[31]) and the steamboat SS Glenlogan (5,800 tons, October 31[32]). In the first three days of November the Hersing unit, positioned north of Sicily, sank four more Italian ships, for a total of almost 2,500 tons overall.[31] On 23 December the German submarine met the near Crete the British steamer SS Benalder and hit her with a torpedo, but she managed to escape and reached the port of Alexandria without being sunk.[33] In the year 1916 the U-36 sunk a total of 12 ships for more than 24,000 tons overall.[31]

Return to the North Sea

At the beginning of 1917 Hersing and his naval unit left the Mediterranean, to support the unrestricted submarine warfare campaign promoted by the German Seekriegsleitung. The new operational theater of the U-21 became then the eastern coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Between 16 and 17 February Hersing intercepted and sank two British merchant ships and two small Portuguese ones off the Portugal coast.[31] Four days later it was the turn of the French freighter Cacique (2,917 tons), sunk in the Bay of Biscay.[34]

On February 22 the U-21 arrived in the northern waters of the Celtic Sea and intercepted the Dutch steamer SS Bandoeng, that was already damaged by another German submarine and was finished by Hersing.[35] The same day the German U-Boot sunk six more Allied ships, five of them were Dutch (the largest of which, the SS Noorderdijk, over 7,000 tons) and one was Norwegian (the SS Normanna, 2,900 tons[36]). A seventh ship, the SS Menado had severe damages but escaped the sinking. In that single day Hersing sank a total of seven ships, for more than 33,000 tons overall.[31]

The German commander moved then his unit in the North Sea waters between Scotland and Norway, and continued there his hunt for the Allied ships: on April 22 he sunk the steamers Giskö and Theodore William. Between 29 and 30 of the same month the U-21 sank the Norwegian Askepot and the Russian bark Borrowdale, cruised off the Irish coast.[37] In the same area the British steamers Adansi and Killarney suffered the same fate on May 6 and 8 respectively. On June 27 Hersing sank the last unit while at the command of his submarine, the Swedish auxiliary barge Baltic, carrying a cargo of timber.[38][39] His service in command of the U-21 ended in September 1918 when, two months before the armistice of the German armed forces he was assigned to the submarine navigation school of Eckernförde as an instructor.[3] During the war Hersing was responsible for the sinking of 40 ships, for a total of more than 113,000 tons; this make him one of the most victorious commanders of the Kaiserliche Marine.[31]

After the war

After the armistice and the definitive end of the war, Hersing was selected to be the responsible for the withdrawal of German troops from the city of Riga (in the present Latvia) between the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919. It is supposed that he was involved in the sinking of the U-21. His former submarine was delivered to the allies after the end of the conflict, and sunk in mysterious circumstances on 22 February 1919, during the transfer from the North Sea to Great Britain, where he should have formally surrendered.[40][41]

In 1920 he was probably involved in the Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup against the newly formed Weimar Republic[42] but had no consequences and remained in the navy. In 1922 he was promoted to Korvettenkapitän (corvette capitain), the highest rank that he reached in his military career.[31] His fame was still so present after the war that the French authorities set up a reward of 20,000 Marks for anyone that would have captured the former submarine commander in the occupied Rhineland areas.[43]

Hersing ended his military service in 1924 due to health reasons, and after that moved with his wife to Rastede, a small town in Lower Saxony. He there surprisingly became a potato farmer, in spite of his glorious past as a naval commander.[20][44]

In 1932 he published his memoir entitled U-21 rettet die Dardanellen ("U-21 saves the Dardanelles").[45] A few years later in 1935, he moved with his wife to Gremmendorf, a district of the city of Münster. Hersing died in 1960 after a long illness; his tomb is currently in the Angelmodde cemetery.[46] The complete collection of his papers and writings is still preserved in the Deutsches U-Boot Museum located in the Niedersachsen town of Altenbruch,[47] in the room dedicated to his memory.[48]

Awards

- Iron Cross (1914)

- 2nd Class

- 1st Class

- Pour le Mérite

- Hanseatic Cross of Lübeck

- Albert Order (Saxony)

- Iron Crescent (Ottoman Empire)

See also

References

- ↑ Branfill-Cook, Roger (2014). Torpedo: The Complete History of the World's Most Revolutionary Naval Weapon. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-84832-215-8.

- ↑ Hadley, Michael L. (1995). Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine. Quebec City: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-7735-1282-9.

- 1 2 Dufeil, Yves (2011). Kaiserliche Marine U-Boote 1914-1918 - Dictionnaire biographique des commandants de la marine imperiale allemande [Biographic dictionary of the German Imperial Navy] (in French). Histomar Publications. p. 31.

- ↑ Gray, Edwyn A. (1994). The U-Boat War: 1914–1918. London: L.Cooper. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-85052-405-9.

- ↑ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2014). The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-107-03690-1.

- ↑ Williamson, Gordon (2012). U-boats pf the Kaiser's navy. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-78096-571-0.

- ↑ "Prima nave affondata da sommergibile" [First ship sunk by a submarine]. marina.difesa.it (in Italian). Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Gray, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Lowell, Thomas (2004). Raiders of the Deep. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 54. ISBN 1-59114-861-8.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Iron Cross 2nd class". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ Mansergh, Ruth (2015). Barrow-in-Furness in the Great War. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-78383-111-1.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Steamer Linda Blanche". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ↑ O'Connell, John F. (2010). Submarine Operational Effectiveness in the 20th Century: Part One (1900–1939). New York: Universe. pp. 144–190. ISBN 978-1-4502-3689-8.

- ↑ Gray, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Burt, R.A. (1988). British Battleships 1889–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 276. ISBN 0-87021-061-0.

- ↑ Gray, p. 124

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "HMS Majestic". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- 1 2 Dando-Collins, Stephen (2011). Crack Hardy: From Gallipoli to Flanders to the Somme, the True Story of Three Australian Brothers at War. Sydney: Random House Australia Pty Ltd. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-86471-024-3.

- 1 2 Gilbert, Martin (2000). La grande storia della prima guerra mondiale [World War I] (in Italian). Milan: Oscar Mondadori. p. 206. ISBN 88-04-48470-5.

- ↑ "Navy Awards During World War I". pourlemerite.org. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "September 1914: Heldentum und Tod - Begeisterung und schleichende Ernüchterung". bad-kreuznach.de (in German). Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Passenger steamer Carthage". Uboat.net. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Gray, pp. 126–128

- ↑ Gray, pp. 129

- ↑ O'Connell, p. 77

- ↑ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2017). German Submarine Warfare in World War I: The Onset of Total War at Sea. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 39. ISBN 9781442269552.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Steamer Belle of France". Uboat.net. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Sondhaus 2014, pp. 181

- ↑ Gibson, R.H.; Prendergast, M. (2002). The German Submarine War 1914-1918. Penzance: Periscope Publishing Ltd. p. 129. ISBN 1-904381-08-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Helgason, Guðmundur. "Otto Hersing". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ↑ "British merchant ships lost to enemy action - Part 1 of 3 - Years 1914, 1915, 1916 in date order". naval-history.net. August 2, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ "Benalder on Clydeships.co.uk". Clydeships.co.uk. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Steamer Cacique". Uboat.net. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ "SS Bandoeng (+1917)". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ "SS Normanna (+1917)". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Pocock, Michael W. "Daily Event for April 30, 2013". maritimequest.com. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ↑ Lowell, p. 76

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Baltic". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ↑ Mansergh, pp. 32

- ↑ Gröner, Erich (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. London: Conway Maritime Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-85177-593-4.

- ↑ "Remembering a Veteran: Captain Otto Hersing, Pour le Mérite, U-boat Commander". roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.it. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Lowell, p. 48

- ↑ Lowell, p. 50

- ↑ Hadley, p. 64

- ↑ Kalitschke, Martin (April 16, 2015). "In der Türkei ein Held: Münsteraner versenkte 40 Schiffe" [A hero in Turkey: a Münsteraner sunk 40 ships]. Westfaeliche Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ↑ "U-boat Archiv Museum Altenbruch". Tracesofwar.com. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ↑ Åkerberg, Dani J. "U-boot Archiv y U-Boot Museum" [U-boot Archives and U-Boot Museum]. www.u-historia.com (in Spanish). Retrieved February 18, 2018.

Bibliography

- Dufeil, Yves (2011). Kaiserliche Marine U-Boote 1914-1918 - Dictionnaire biographique des commandants de la marine imperiale allemande [Biographic dictionary of the German Imperial Navy] (in French). Histomar Publications.

- Gibson, R.H.; Prendergast, M. (2002). The German Submarine War 1914-1918. Penzance: Periscope Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-904381-08-1.

- Gilbert, Martin (2000). La grande storia della prima guerra mondiale [World War I] (in Italian). Milan: Oscar Mondadori. ISBN 88-04-48470-5.

- Gray, Edwyn A. (1994). The U-Boat War: 1914–1918. London: L.Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-405-9.

- Hadley, Michael L. (1995). Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine. Quebec City: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1282-9.

- Lowell, Thomas (2004). Raiders of the Deep. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-861-8.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2017). German Submarine Warfare in World War I: The Onset of Total War at Sea. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 9781442269552.

External links

- "Otto Hersing". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). 1969. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "Otto Hersing". Uboat.net. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- "Official website of the German U-boat Museum". Retrieved January 2, 2018.