Operation Spring Awakening

Operation Spring Awakening (Unternehmen Frühlingserwachen) (6 – 16 March 1945) was the last major German offensive of World War II. It took place in Hungary on the Eastern Front. This offensive was also referred to in Germany as the Plattensee Offensive and in the Soviet Union as the Balaton Defensive Operation (6 – 15 March 1945).

The offensive began in great secrecy on 6 March 1945 with an attack near Lake Balaton, the area included some of the last oil reserves still available to the Axis. The operation involved many German units withdrawn from the failed Ardennes Offensive on the Western Front, including the 6th Panzer Army and its subordinate Waffen-SS divisions. The operation was a failure for Germany.

German plan

After the Ardennes offensive failed, in Hitler’s estimation, the Nagykanizsa oilfields southwest of Lake Balaton were the most strategically valuable reserves on the Eastern Front.[11] Hitler ordered Sepp Dietrich's 6th SS Panzer Army to take the lead and move to Hungary in order to protect the oilfields and refineries there.[12]

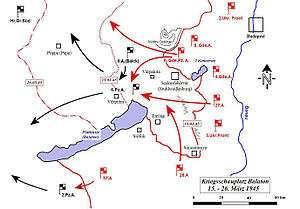

The Germans planned to attack against Soviet General Fyodor Tolbukhin's 3rd Ukrainian Front.[13] The 6th Panzer Army was responsible for the primary thrust of the German attack. The army was to advance from an area north of Lake Balaton on a wide front. They were to push east through the Soviet 27th Army and to the Danube River. After reaching the river, one part of the army would turn north creating a northern spearhead. The northern spearhead would advance through the Soviet 6th Guards Tank Army and move along the Danube River to retake Budapest, which had been captured on 13 February 1945. Another part of 6th SS Panzer Army would then turn south and create a southern spearhead. The southern spearhead would move along the Sió to link up with units from German Army Group E, which was to thrust north through Mohács. If successful, the meeting of the southern spearhead and of Army Group E would encircle both the Soviet 26th Army and the Soviet 57th Army.[13]

German 6th Army would keep the Soviet 27th Army engaged while it was surrounded. Likewise, the German 2nd Panzer Army would advance from an area south of Lake Balaton towards Kaposvár and keep the Soviet 57th Army engaged. The Hungarian Third Army was to hold the area north of the attack and to the west of Budapest.[13]

Soviet preparation

By the second half of February, Soviet intelligence identified large German tank formations in western Hungary, and soon realized that preparation for a major offensive was underway.[13] Using the experience gained in the Battle of Kursk, the Soviets built multi-layered anti-tank defenses, using 65% of available artillery to create 66 anti-tank ambush points over 83 km of front in Lake Balaton area. The depth of the defense zone reached up to 25–30 km. To ensure sufficient supply of war materials and fuel, additional temporary bridges and gas pipelines were built on the Danube River.[13]

Between February 18 and March 3 the 233rd Rifle Division had dug 27 kilometers of trenches, 130 gun and mortar positions, 113 dugouts, 70 command posts and observation points, and laid 4,249 antitank and 5,058 antipersonnel mines, all this on a frontage of 5 kilometers. Although there were no tanks in this defensive zone, there was an average of 17 anti-tank guns per kilometer forming 23 tank killing grounds[14].

Order of battle

The Axis forces:

- Elements of the German Army Group South

- German 6th SS Panzer Army – Included the 1st SS Panzer Corps with Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler Division and Hitlerjugend Division, and the 2nd SS Panzer Corps with Das Reich Division and Hohenstaufen Division

- German Second Panzer Army

- German 6th Army

- Hungarian Third Army

- Elements of the German Army Group E)

- SS Division Handschar

The Soviet forces:

German attack

On 6 March 1945, the German 6th Army, joined by the 6th SS Panzer Army launched a pincer movement north and south of Lake Balaton. Ten panzer and five infantry divisions, including a large number of new heavy Tiger II tanks, struck 3rd Ukrainian Front, hoping to reach the Danube and link up with the German 2nd Panzer Army forces attacking south of Lake Balaton.[15] The attack was spearheaded by the 6th SS Panzer Army and included elite units such as the LSSAH division. Dietrich's army made "good progress" at first, but as they drew near the Danube, the combination of the muddy terrain and strong Soviet resistance ground them to a halt.[16]

By 14 March, Operation Spring Awakening was at risk of failure. The 6th SS Panzer Army was well short of its goals. The 2nd Panzer Army did not advance as far on the southern side of Lake Balaton as the 6th SS Panzer Army had on the northern side. Army Group E met fierce resistance from the Bulgarian First Army and Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavian partisan army, and failed to reach its objective of Mohács.

German losses were grave. Heeresgruppe Süd lost 15,117 casualties in the first eight days of the offensive. The 6th Panzer Army and the 6th Army had only 332 tanks operational of the original approximately 1,000 operational.

On the 15th, strength returns on this day show the Hohenstaufen with 35 Panther tanks, 20 Panzer IVs, 32 Jagdpanzers, 25 Sturmgeschützes and 220 other self-propelled weapons and armored cars. 42% of these vehicles were damaged, under short or long-term repair. The Das Reich Division had 27 Panthers, 22 Panzer IVs, 28 Jagdpanzers and 26 Sturmgeschützes on hand (the number of under repair are not available)[17].

Soviet counterattack

On 16 March, the Soviets forces counterattacked in strength. The Germans were driven back to the positions they had held before Operation Spring Awakening began.[18] The overwhelming numerical superiority of the Red Army made any defense impossible, yet Hitler somehow had believed victory was attainable.[19]

On 22 March, the remnants of the 6th SS Panzer Army withdrew towards Vienna. By 30 March, the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed from Hungary into Austria. By 4 April, the 6th SS Panzer Army was already in the Vienna area desperately setting up defensive lines against the anticipated Soviet Vienna Offensive. Approaching and encircling the Austrian capital were the Soviet 4th and 6th Guards Tank, 9th Guards, and 46th Armies.[18]

The Soviet's Vienna Offensive ended with the fall of the city on 13 April. By 15 April, the remnants of the 6th SS Panzer Army were north of Vienna, facing the Soviet 9th Guards and 46th Armies. By 15 April, the depleted German 6th Army was north of Graz, facing the Soviet 26th and 27th Armies. The remnants of the German 2nd Panzer Army were south of Graz in the Maribor area, facing the Soviet 57th Army and the Bulgarian First Army. Between 25 April and 4 May, the 2nd Panzer Army was attacked near Nagykanizsa during the Nagykanizsa–Körmend Offensive.

Some Hungarian units survived the fall of Budapest and the destruction which followed when the Soviets counterattacked after Operation Spring Awakening. The Hungarian Szent László Infantry Division was still indicated to be attached to the German 2nd Panzer Army as late as 30 April. Between 16 and 25 March, the Hungarian Third Army had been destroyed about 40 kilometres (25 mi) west of Budapest by the Soviet 46th Army which was driving towards Bratislava and the Vienna area.

On March 19, Soviet recapture the last territory lost during the 13‑day Axis offensive. Sepp Dietrich, commander of the Sixth SS Panzer Army tasked with defending the last sources of petroleum controlled by the Germans, joked that “6th Panzer Army is well named—we have just six tanks left.”[20]

The failure of the operation resulted in the "armband order" that was issued to Sepp Dietrich by Adolf Hitler, who claimed that the troops, and more importantly, the Leibstandarte, "did not fight as the situation demanded."[21] As a mark of disgrace, the Waffen-SS units involved in the battle were ordered to remove their cuff titles. Dietrich did not relay the order to his troops.[16]

See also

- History of Germany during World War II

- Hungary during the Second World War

- Military history of Bulgaria during World War II

- Battle of Budapest – 1944/45

- Battle of the Transdanubian Hills – 1945

- Nagykanizsa–Körmend Offensive – 1945

- Prague Offensive – 1945

- Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front

- German 6th SS Panzer Army

- German Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Division

- Hungarian Third Army

- Bulgarian First Army

Notes

References

Citations

- 1 2 Frieser et al. 2007, p. 930.

- 1 2 3 4 Frieser et al. 2007, p. 941.

- ↑ Frieser et al. 2007, p. 942.

- ↑ Tucker-Jones, Anthony (2016). The Battle for Budapest. ISBN 978-1473877320.

- 1 2 Frieser et al. 2007, p. 953.

- ↑ Frieser et al. 2007, p. 952.

- ↑ O. Baronov, Balaton Defense Operation, Moscow, 2001, P.82-106

- ↑ G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, ISBN 1-85367-280-7, Page 110

- ↑ G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, p. 156-7

- ↑ G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, p.156-7

- ↑ Duffy 2002, p. 293.

- ↑ Seaton 1971, p. 537.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Higgins, David R. (2014). Jagdpanther vs SU-100. Eastern Front 1945. Osprey Publishing.

- ↑ https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/hitlers-last-offensive-operation-spring-awakening/

- ↑ Glantz & House 1995, p. 253.

- 1 2 Stein 1984, p. 238.

- ↑ https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/hitlers-last-offensive-operation-spring-awakening/

- 1 2 Dollinger 1967, p. 182.

- ↑ Ziemke 1968, p. 450.

- ↑ https://ww2days.com/germans-trapped-in-hungarian-capital-2.html

- ↑ Dollinger 1967, p. 198.

Bibliography

- Dollinger, Hans (1967) [1965]. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. New York: Bonanza. ISBN 978-0-517-01313-7.

- Duffy, Christopher (2002). Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany, 1945. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1624-0.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz; Schmider, Klaus; Schönherr, Klaus; Schreiber, Gerhard; Ungváry, Kristián; Wegner, Bernd (2007). Die Ostfront 1943/44 – Der Krieg im Osten und an den Nebenfronten [The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts]. Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg [Germany and the Second World War] (in German). VIII. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

- Fritz, Stephen (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81313-416-1.

- Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, Kansas: Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-0717-X.

- Seaton, Albert (1971). The Russo-German War, 1941–45. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-21376-478-4.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1968). Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East. Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History – U.S. Army. ASIN B002E5VBSE.