Nightmare

| Nightmare | |

|---|---|

| |

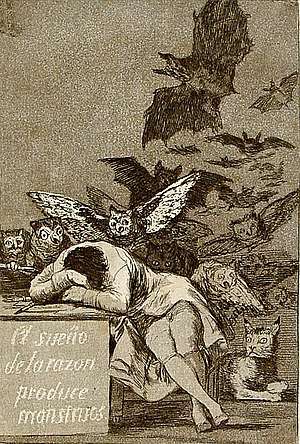

| The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Francisco de Goya, c.1797) |

A nightmare, also called a bad dream,[1] is an unpleasant dream that can cause a strong emotional response from the mind, typically fear but also despair, anxiety and great sadness. However, psychological nomenclature differentiates between nightmares and bad dreams, specifically, people remain asleep during bad dreams whereas nightmares awaken individuals. Further, the process of psychological homeostasis employs bad dreams to protect an individual's Homeostatically Protected Mood (HPMood) from the impact of elevated anxiety levels. During sleep, nightmares indicate the failure of the homeostatic system employing bad dreams to extinguish anxiety accumulated throughout the day. [2] The dream may contain situations of discomfort, psychological or physical terror or panic. After a nightmare, a person will often awaken in a state of distress and may be unable to return to sleep for a short period of time.[3]

Nightmares can have physical causes such as sleeping in an uncomfortable position or having a fever, or psychological causes such as stress or anxiety. Eating before going to sleep, which triggers an increase in the body's metabolism and brain activity, is a potential stimulus for nightmares.[4]

Recurrent nightmares may require medical help, as they can interfere with sleeping patterns and cause insomnia.

Cause

Scientific research shows that nightmares may have many causes. In a study focusing on children, researchers were able to conclude that nightmares directly correlate with the stress in children's lives. Children who experienced the death of a family member or a close friend or know someone with a chronic illness have more frequent nightmares than those who are only faced with stress from school or stress from social aspects of daily life.[5] A study researching the causes of nightmares focuses on patients who have sleep apnea. The study was conducted to determine whether or not nightmares may be caused by sleep apnea, or being unable to breathe. In the nineteenth century, authors believed that nightmares were caused by not having enough oxygen, therefore it was believed that those with sleep apnea had more frequent nightmares than those without. The hypothesis, however, was proven wrong and the results actually showed that healthy people have more nightmares than the sleep apnea patients.[6]

In Stephen LaBerge's book entitled Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming (1990) he outlines a possible reason for how dreams are formulated and why nightmares occur with a high frequency. A dream starts with an individual thought or scene, in his example he uses the scene of walking down a dimly lit street. Since dreams are not predetermined, your brain responds to the situation by either thinking a good thought or a bad thought, and the dream framework follows from there. Since the prominence of bad thoughts in dreams is higher than good, the dream will proceed to be a nightmare.[7]

There is a popular view, featured in the story A Christmas Carol, that eating cheese before sleep can cause nightmares, but there is little scientific evidence for this.[8]

Possible effects

A study involving a large group of undergraduate students analyzes the effects of nightmares on the quality of sleep. The study showed that the participants experienced abnormal sleep architecture and that the results of having a nightmare during the night were very similar to those of people who have insomnia. This means that, like insomniacs, people who have nightmares do not get as much rest as those who do not have chronic nightmares. Therefore, they experience a lesser quality of sleep than others. This is thought to be caused by frequent nocturnal awakenings and fear of falling asleep.[9]

Treatment

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung seemed to have shared a belief that people frequently distressed by nightmares could be re-experiencing some stressful event from the past.[10] Both perspectives on dreams suggest that therapy can provide relief from the dilemma of the nightmare experience.

Halliday (1987), grouped treatment techniques into four classes. Direct nightmare interventions that combine compatible techniques from one or more of these classes may enhance overall treatment effectiveness:[11]

- Analytic and cathartic techniques

- Story-line alteration procedures

- Face-and-conquer approaches

- Desensitization and related behavioral techniques.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Reccurring post-traumatic stress disorder nightmares in which real traumas are re-experienced respond well to a technique called imagery rehearsal. First described in the 1996 book Trauma and Dreams[12] by Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett, this contemporary dream interpretation involves dreamers coming up with alternative, mastery outcomes to the nightmares, mentally rehearsing those outcomes awake, and then reminding themselves at bedtime that they wish these alternate outcomes should the nightmares reoccur. Research has found that this technique not only reduces the occurrence of nightmares and insomnia,[13] but also improves other daytime PTSD symptoms.[14] According to Bret Moore and Barry Kraków, the most common variations of Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) "relate to the number of sessions, duration of treatment, and the degree to which exposure therapy is included in the protocol".[15] Another kind of treatment not only helping the reduction of nightmares, sleep disturbance, and other PTSD symptoms is prazosin. There have been multiple studies conducted under placebo-controlled conditions. (Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:371–373)

A comprehensive model has been put forth by Krakow and Zadra (2006) that includes four group treatment sessions, ~2.25 to 2.5 hr in length. The first two sessions focus on how nightmares are closely connected to insomnia and how they become an independent symptom or disorder that warrants individually tailored and targeted intervention. The last two sessions focus on the imagery system and how IRT can reshape and eliminate nightmares through a relatively straightforward process akin to cognitive restructuring via the human imagery system. First, the patient is asked to select a nightmare, but for learning purposes the choice would not typically be one that causes a marked degree of distress. Second, and most commonly, guidance is not provided on how to change the disturbing content of the dream; the specific instruction developed by Joseph Neidhardt is "change the nightmare anyway you wish" (Neidhardt et al., 1992). In turn, this step creates a "new" or "different" dream, which may or may not be free of distressing elements. Our instructions, unequivocally, do not make a suggestion to the patient to make the dream less distressing or more positive or to do anything other than "change the nightmare anyway you wish." Last, the patient is instructed to rehearse the "new dream" through imagery and to ignore the old nightmare.p. 234[15]

Some people may experience recurring nightmares due to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or they may have some other source of anxiety that influences their dreams at night.[10] Whatever the cause, there are treatments available, some of them medical and some psychological. While most treatments are meant for people who have a true disorder, the techniques discussed above will work well for any person dealing with nightmares.[10]

Epidemiology

Fearfulness in waking life is correlated with nightmares.[16] Studies of dreams have estimated that about 75% of the time, the emotions evoked by dreams are negative.[16] However, it is worth noting that people are more likely to remember unpleasant dreams.

One definition of "nightmare" is a dream which causes one to wake up in the middle of the sleep cycle and experience a negative emotion, such as fear. This type of event occurs on average once per month. They are not common in children under five, but they are more common in young children (25% experiencing a nightmare at least once per week), most common in teenagers, and common in adults (dropping in frequency about one third from age 25 to 55).[16]

Etymology

The word "nightmare" is derived from the Old English "mare", a mythological demon or goblin who torments others with frightening dreams.[17] Subsequently, the prefix "night-" was added to stress the dream aspect. The word "nightmare" is cognate with the older Dutch term nachtmerrie and German Nachtmahr (dated).

See also

- False awakening

- Hag in folklore

- Lucid dream

- Mare (folklore)

- Mora (mythology)

- Moroi (folklore)

- Night terror

- Nightmare disorder

- Nocnitsa

- Sleep disorder

- Sleep paralysis

- Horror and terror

- A Christmas Carol

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nightmares. |

References

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "nightmare". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ Tunbridge, Lindsay (2014), International Journal of Dream Research, Vol 7 Issue 1, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-ijodr-119592

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, TR, p. 631

- ↑ Stephen,, Laura (2006). "Nightmares". Psychologytoday.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007.

- ↑ Schredl, Michael, et al. "Nightmares and Stress in Children." Sleep and Hypnosis 10.1 (2008): 19-25. ProQuest. Web. 29 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Schredl, Michael, et al. "Nightmares and Oxygen Desaturations: Is Sleep Apnea Related to Heightened Nightmare Frequency?" Sleep and Breathing 10.4 (2006): 203-9. ProQuest. Web. 24 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Stephen, LaBerge (1990). Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming. New York: BALLANTINE BOOKS. pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Hammond, Claudia (17 April 2012). "Does cheese give you nightmares?". BBC. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Simor, Pé, et al. "Disturbed Dreaming and Sleep Quality: Altered Sleep Architecture in Subjects with Frequent Nightmares."European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience 262.8 (2012): 687-96. ProQuest. Web. 24 Apr. 2014.

- 1 2 3 Coalson 1985, Web

- ↑ Halliday 1987

- ↑ ISBN 0-674-00690-9

- ↑ Davis, J. L.; Wright, D. C. (2005). "Case Series Utilizing Exposure, Relaxation, and Rescripting Therapy: Impact on Nightmares, Sleep Quality, and Psychological Distress". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 3 (3): 151–157. doi:10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_3. PMID 15984916.

- ↑ Krakow, B.; Hollifield, M.; Johnston, L.; Koss, M.; Schrader, R.; Warner, T. D.; Tandberg, D.; Lauriello, J.; McBride, L. (2001). "Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for Chronic Nightmares in Sexual Assault Survivors with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 286 (5): 537. doi:10.1001/jama.286.5.537.

- 1 2 Lu, M.; Wagner, A.; Van Male, L.; Whitehead, A.; Boehnlein, J. (2009). "Imagery rehearsal therapy for posttraumatic nightmares in U.S. Veterans". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 22 (3): 236–239. doi:10.1002/jts.20407. PMID 19444882. , p. 234

- 1 2 3 The Science Behind Dreams and Nightmares, Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio. 30 October 2007.

- ↑ Liberman, Anatoly (2005). Word Origins And How We Know Them. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-19-538707-0. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

Further reading

- Anch, A. M.; Browman, C. P.; Mitler, M. M.; Walsh, J. K. (1988). Sleep: A Scientific Perspective. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Harris, J. C. (2004). "The Nightmare". Archives of General Psychiatry. 61 (5): 439–40. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.439. PMID 15123487.

- Husser, J.-M.; Mouton, A., eds. (2010). Le Cauchemar dans les sociétés antiques. Actes des journées d'étude de l'UMR 7044 (15–16 Novembre 2007, Strasbourg). Paris: De Boccard. (in French)

- Jones, Ernest (1951). On the Nightmare. ISBN 0-87140-912-7.

- Forbes, D.; et al. (2001). "Brief Report: Treatment of Combat-Related Nightmares Using Imagery Rehearsal: A Pilot Study". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 14 (2): 433–442. doi:10.1023/A:1011133422340.

- Siegel, A. (2003). "A mini-course for clinicians and trauma workers on posttraumatic nightmares".

- Burns, Sarah (2004). Painting the Dark Side : Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century America. Ahmanson-Murphy Fine Are Imprint. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23821-4.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (1999). Gothic: Four Hundred Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin. North Point Press. pp. 160–61.

- Hill, Anne (2009). What To Do When Dreams Go Bad: A Practical Guide to Nightmares. Serpentine Media. ISBN 1-887590-04-8.

- Simons, Ronald C.; Hughes, Charles C., eds. (1985). Culture-Bound Syndromes. Springer.

- Sagan, Carl (1997). The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.

- Coalson, Bob (1995). "Nightmare help: Treatment of trauma survivors with PTSD". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 32 (3): 381–388. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.32.3.381.

- "Nightmares? Bad Dreams, or Recurring Dreams? Lucky You!". Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Halliday, G. (1987). "Direct psychological therapies for nightmares: A review". Clinical Psychology Review. 7: 501–523. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(87)90041-9.

- Doctor, Ronald M.; Shiromoto, Frank N., eds. (2010). "Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT)". The Encyclopedia of Trauma and Traumatic Stress Disorders. New York: Facts on File. p. 148.

- Mayer, Mercer (1976). There's a Nightmare in My Closet. [New York]: Puffin Pied Piper.

- Moore, Bret A.; Kraków, Barry (2010). "Imagery rehearsal therapy: An emerging treatment for posttraumatic nightmares in veterans". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2 (3): 232–238. doi:10.1037/a0019895.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

| Look up nightmare in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

![]()