Mycenaean pottery

Mycenaean pottery was produced from c. 1600 BC to c. 1000 BC by Mycenaean Greek potters. It is divided by archaeologists into a series of stillages on the slopes of hills to, eventually, the dominating culture of Ancient Greece.

Mycenaeans rose in prominence around 1600 BC and stayed in control of Greece until about 1100 BC. Evidence shows that they spoke an early form of Greek. They took control of Crete c. 1450 BC.

An abundance of Mycenaean pottery is found in Italy and Sicily, suggesting that they were in contact and traded with the Mycenaeans.[1]

Late Helladic I-IIA (c. 1675/1650 – 1490/1470 BC)

There is some question as to how much of the pottery of this age relies on Minoan pottery for both their shapes and the patterns. For at least the first half of the seventeenth century BC there is only a small portion of all pottery produced that is in the Minoan style.

Late Helladic I-IIA pottery can be distinguished by the use of a more lustrous paint than the predecessors. While this is more common during this age, there was a considerable amount of pottery produced in the Middle Helladic period style, using matte paints and middle Helladic shapes.

Where the first recognizably Mycenaean pottery emerged is still under debate. Some believe that this development took place in the northeast Peloponnese (probably in the vicinity of Mycenae). There is also evidence that suggests that the style appeared in the southern Peloponnese (probably Lanconia) as a result of the Minoan potters taking up residence at coastal sites along the Greek Mainland.[2]

Late Helladic I (c. 1675/1650 – 1600/1550 BC)

The pottery during this period varies greatly in style from area to area. Due to the influence of Minoan Crete, the further south the site, the more the pottery is influenced by Minoan styles.

The easiest way to distinguish the pottery of this period from that of the late Middle Helladic is the use of a fine ware that is painted in a dark-on-light style with lustrous paints. This period also marks the appearance of a fine ware that is coated all over with paint varying from red and black in color. This ware is monochrome painted and is directly descended from grey and black Minyan ware (which disappear during LH I). A form of the yellow Minyan style also appears in this period, merging into Mycenaean unpainted wares.

Additionally, Mycenaean art is different from that of the Minoans in that the different elements of a work are distinguished from each other much more clearly, whereas Minoan art is generally more fluid. [3]

There is also some carry-over of matte-painted wares from the Middle Helladic period into LH I. The majority of large closed vessels that bear any painted decorations are matte. They are generally decorated in two styles of matte paints known as Aeginetan Dichrome and Mainland Polychrome.

Some of the preferred shapes during this period were the vapheio cup, semi globular cup, alabastron, and piriform jar.

| Shape | Example |

|---|---|

| Vapheio cup | |

| Semi globular cup | |

| Alabastron | |

| Piriform jar |

Late Helladic IIA (c. 1600/1550 – 1490/1470 BC)

During this phase there is a drastic increase in the amount of fine pottery that is decorated with lustrous paints. An increase in uniformity in the Peloponnese (both in painting and shape) can be also seen at this time. However, Central Greece is still defined by Helladic pottery, showing little Minoan influence at all, which supports the theory that Minoan influence on ceramics traveled gradually from south to north.

By this period, matte-painted pottery is much less common and the Grey Minyan style has completely disappeared. In addition to the popular shapes of LH I goblets, jugs, and jars have increased in popularity.[2]

Late Helladic IIB-IIIA1 (c. 1490/1470 – 1390/1370 BC)

During this phase, Minoan civilization slowly decreased in importance and eventually the Mycenaeans rose in importance, possibly even temporarily being in control of the Cretan palace of Knossos. The mainland pottery began to break away from Minoan styles and Greek potters started creating more abstract pottery as opposed to the previously naturalistic Minoan forms. This abstract style eventually spread to Crete as well.

Late Helladic IIB (c. 1490/1470 – 1435/1405 BC)

During this period the most popular style was the Ephyraean style; most commonly represented on goblets and jugs. This style is thought to be a spin-off of the Alternating style of LM IB. This style has a restricted shape range, which suggests that potters may have used it mostly for making matching sets of jugs, goblets and dippers.

It is during LH IIB that the dependence on Minoan ceramics is completely erased. In fact, looking at the pottery found on Crete during this phase suggests that artistic influence is now flowing in the opposite direction; the Minoans are now using Mycenaean pottery as a reference.

Ivy, lilies, and nautili are all popular patterns during this phase and by now there is little to no matte painting.

Late Helladic IIIA1 (c. 1435/1405 – 1390/1370 BC)

During LH IIIA1, there are many stylistic changes. Most notably, the Mycenaean goblet begins to lengthen its stem and have a more shallow bowl. This stylistic change marks the beginning of the transformation from goblet to kylix. The vapheio cup also changes into an early sort of mug and becomes much rarer. Also during this period, the stirrup jar becomes a popular style and naturalistic motifs become less popular.

Late Helladic IIIA2-B (c. 1390/1370 – 1190 BC)

Not long after the beginning of this stage there is evidence of major destruction at the palace at Knossos on Crete. The importance of Crete and Minoan power decreases and Mycenaean culture rises in dominance in the southern Aegean. It was during this period that the Levant, Egypt and Cyprus came into close and continuous contact with the Greek world. Masses of Mycenaean pottery found in excavated sites in the eastern Mediterranean show that not only were these ancient civilizations in contact with each other, but also had some form of established trade.

The Koine style (from Greek koinos = "common") is the style of pottery popular in the first three quarters of this era. This form of pottery is thus named for its intense technical and stylistic uniformity, over a large area of the eastern and central Mediterranean. During LH IIIA it is virtually impossible to tell where in Mycenaean Greece a specific vase was made. Pottery found on the islands north of Sicily is almost identical to that found in Cyprus and the Levant. It is only during the LH IIIB period that stylistic uniformity decreased; around the same time that the amount of trade between the Peloponnese and Cyprus dramatically decreased.

Late Helladic IIIA2 (c. 1390/1370 – 1320/1300 BC)

It is in this period that the kylix truly becomes the dominant shape of pottery found in settlement deposits. The stirrup jar, piriform jar, and alabastron are the shapes most frequently found in tombs from this era. Also during LH IIIA2 two new motifs appear: the whorl shell and LH III flower. These are both stylized rather than naturalistic, further separating Mycenaean pottery from Minoan influence.

Excavations at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt have found large deposits of Aegean pottery. These findings provide excellent insight to the shape range (especially closed forms) of Mycenaean pottery. By this time, monochrome painted wares were almost exclusively large kylikes and stemmed bowls while fine unpainted wares are found in a vast range of shapes.

Late Helladic IIIB (c. 1320/1300 – 1190 BC)

The presence of the deep bowl as well as the conical kylix in this age is what allows one to differentiate from LH IIIA. During LH IIIB paneled patterns also appear. Not long into this phase the deep bowl becomes the most popular decorated shape, although for unpainted wares the kylix is still the most produced.

One can further distinguish the pottery from this period into two sub-phases:

- LH IIIB1: this phase is characterized by an equal presence of both painted deep bowls and kylikes. The kylikes at this time are mostly Zigouries.

- LH IIIB2: during this phase there is an absence of decorates kylikes and deep bowl styles further develop into the Rosette form.

It is unknown how long each sub-phase lasted, but by the end of LH IIIB2 the palaces of Mycenae and Tiryns and the citadel at Midea had all been destroyed. The palace of Pylos was also destroyed at some point during this phase, but it is impossible to tell when in relation to the others the destruction took place.

Late Helladic IIIC (c. 1190 – 1050/1025 BC)

During this period, the differences in ceramics from different regions become increasingly more noticeable, suggesting further degradation of trade at this time. Other than a brief 'renaissance' period that took place mid-twelfth century that brought some developments, the pottery begins to deteriorate. This decline continues until the end of LH IIIC, where there is no place to go but up in terms of technical and artistic pottery.

The shapes and decorations of the ceramics discovered during this final period show that the production of pottery was reduced to little more than a household industry, suggesting that this was a time of poverty in Greece.

It is possible to divide this phase into several different sub-phases.

Early phase

At this time, the medium band form of deep bowl appears and most painted shapes in this phase have linear decoration. Occasionally new shapes (like the carinated cup) and new decorations appear, helping to distinguish wares from this period from those of earlier phases.

Around the same time as the destruction of the great palaces and citadels is recovered an odd class of handmade pottery lacking any ancestry in the Mycenaean world. Similar pottery is also found in other areas both to the East (e.g. Troy, Cyprus and Lebanon) and to the West (Sardinia and Southern Italy). Most of the scholars in recent times agree that such a development is probably to be interpreted as the result of long-range connections with the Central Mediterranean area (and in particular with southern Italy),[4] and some have connected this with the appearance in the Eastern Mediterranean of the so-called Sea Peoples[5]

Developed phase

In this sub-phase there is increased development in pattern painted pottery. Scenes of warriors (both foot soldiers and on chariots) become more popular. The majority of the developments however are representational motifs in a variety of regional styles:

| Style | Region | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Closed style | Argolid | |

| Octopus style | eastern Attica, Cyclades, Dodecanese | |

| Pictorial or Fantastic style | Lefkandi | |

| Fringed style | Crete |

Late phase

There is very little pottery found during this phase, thus not providing much information. It is clear, however, that the bountiful decorations of the developed phase are no longer around. When patterns did occur in this phase, they were very simple; most of the pottery was decorated with a simple band or a solid coat of paint.

Technology

The earliest form of the potter's wheel was developed in the Near East around 3500 BC. This was then adopted by the people of Mesopotamia who later altered the performance of the wheel to make it faster. Around 2000 years later, during the Late Helladic period, Mycenaeans adopted the wheel.

The idea behind the pottery wheel was to increase the production of pottery. The wheels consisted of a circular platform, either made of baked clay, wood or terracotta and were turned by hand; the artist usually had an assistant that turned the wheel while he molded the clay.

Clay is dug from the ground, checked for impurities and placed on the wheel to be molded. Once the potter gets the shape he desires, the potter stops the wheel, allowing the access water to run of. The artist then spins it again to ensure the water is off then it is placed in a kiln. The kiln was usually a pit dug in the ground and heated by fire; these were estimated to reach a temperature of 950 degree Celsius (1,742 degree Fahrenheit). Later kilns were built above ground to be easier to maintain and ventilate. During the firing of the pottery, artists went through a three-phase firing in order to achieve the right colour (further reading).

Many historians question how Mycenaean potter's developed the technique of glossing their pottery. Some speculate that there is a "elite or a similar clay mineral in a weak solution"[6] of water. This mixture is then applied to the pottery and placed in the kiln to set the surface. Art Historians suggest that the "black areas on Greek pots are neither pigment nor glaze but a slip of finely sifted clay that originally was of the same reddish clay used."[7]

Considering the appearance of the pottery, many Mycenaean fragments of pottery that have been uncovered, has indicated that there is colour to the pottery. Much of this colouring comes from the clay itself; pigments are absorbed from the soil. Vourvatsi pots start off with a pink clay "due merely to long burial in the deep red soil of the Mesmogia". "The colours of the clay vary from white and reds to yellows and browns. The result of the pottery is due to the effects of the kiln; this ties in the three-phases of firing."[8]

- Phase One: Oxidizing. Oxygen is added to the kiln, thus creates the slip and pot to turn red

- Phase Two: Reducing. The shutter in the kiln is closed, reducing the amount of oxygen the pottery receives, this causes both the slip and pot to turn black.

- Phase Three: Re-oxidizing. Oxygen is then released back into the kiln, causing the coarser material to turn red and the smother silica-laden slip to remain black.[9]

Artists used a variety of tools to engrave designs and pictures onto the pottery. Most of the tools used were made up of stones, sticks, bones and thin metal picks. Artists used boar-hair brushes and feathers used to distribute the sifted clay evenly on the pottery.

Art history

Forms of pottery

There are many different and distinct forms of pottery that can have either very specific or multi-functional purposes. The majority of forms, however are for holding or transporting liquids.

The form of a vessel can help determine where it was made, and what it was most likely used for. Ethnographic analogy and experimental archaeology have recently become popular ways to date a vessel and discover its function.

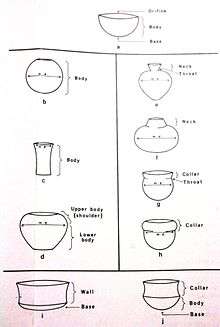

Anatomy

The anatomy of a vessel can be separated into three distinct parts: orifice, body and base. There are many different shapes depending on where the vessel was made, and when.

The body is the area between the orifice (opening) and base (bottom). The maximum diameter of a vessel is usually at the middle of the body or a bit higher. There are not many differences in the body; the shape is pretty standard throughout the Mycenaean world.

The orifice is mouth of the vessel, and is subject to many different embellishments, mostly for functional use. The opening is further divided into two categories:

- Unrestricted: an unrestricted orifice is when the opening is equal to or greater than the maximum diameter.

- Restricted: contrarily, is when the opening is less than the maximum diameter.

The space between the orifice and the body can be divided into two specific shapes:

- Neck: a restriction of the opening that is above the maximum diameter.

- Collar: an extension of the opening that does not reduce the orifice.

The base is the underside of the vessel. It is generally flat or slightly rounded so that it can rest on its own, but certain wares (especially of the elite variety) have been known to be extremely rounded or pointed.

Shapes

There are many different shapes of pottery found from the Mycenaean world. They can serve very specific tasks or be used for different purposes. Some popular uses for pottery at this time are: saucepans, storage containers, ovens, frying pans, stoves, cooking pots, drinking cups and plates.

Some shapes with specific functions are:

- Stamnos: a wine jar

- Krateriskos: miniature mixing bowl

- Aryballos, Lekythoi, Alabastra: for holding precious liquids

Many shapes can be used for a variety of things, such as jugs (oinochoai) and cups (kylikes). Some, however, have very limited uses; such as the kyathos which is used solely to transfer wine into these jugs and cups.

Throughout the different phases of Mycenaean pottery different shapes have risen and fallen in prominence. Others evolve from previous forms (for example, the Kylix (drinking cup) evolved from the Ephyraean goblet).[10]

Ephyrean goblet

This goblet is the finest product of a Mycenaean potter's craft. It is a stout, short stemmed goblet that is Cretan in origin with Mycenaean treatment. Its decoration is confined to the center of each side and directly under the handles.

Stirrup jar

The stirrup jar is used for storage and transportation, most commonly of oil and wine that was invented in Crete. Its body can be globular, pear-shaped or cylindrical. The top has a solid bar of clay shaped in two stirrup handles and a spout.

Alabastron

The alabastron is the second most popular shape (behind the stirrup jar). It is a squat jar with two to three ribbon-handles at the opening.

Function

Vessel function can be broken down into three main categories: storage, transformation/processing and transfer. These three categories can be further broken down by asking questions such as:

- hot or cold?

- liquid or dry?

- frequency of transactions?

- duration of use?

- distance carried

The main problem with pottery is that it is very fragile. While well-fired clay is virtually indestructible, if bumped or dropped it will shatter. Other than this, it is very useful in keeping rodents and insects out and as it can be set directly into a fire it is very popular.

There are a few different classes of pottery, generally separated into two main sections: utilitarian and elite. Utilitarian pottery is generally plainwares, sometimes with decorations, made for functional, domestic use, and constitutes the bulk of the pottery made. Elite pottery is finely made and elaborately decorated with great regard for detail. This form of pottery is generally made for holding precious liquids and for decoration.

Geometric style

The geometric style of decorating pottery has been popular since Minoan times. Although it did decrease in abundance for some time, it resurfaced c. 1000 BC. This form of decoration consists of light clay and a dark, lustrous slip of design. Around 900 BC it became very popular in Athens and different motifs; such as abstract animals and humans began to appear. Among the popular shapes for geometric pottery are:

- Circles

- Checkers

- Triangles

- Zigzags

- Meander (art)

Production centers

The two main production centers during Mycenaean times were Athens and Corinth. Attributing pottery to these two cities is done based on two distinct and different characteristics: shapes (and color) and detailed decoration.

In Athens the clay fired rich red and decorations tended towards the geometric style. In Corinth the clay was light yellow in color and they got their motifs from more natural inspirations.

Phylakopi classification

This classification system is based on the Mycenaean pottery found at the third city of Phylakopi on the island of Milos. This has been divided into four phases

- In this first phase, black matte decoration is the only style to be found. Popular motifs are straight bands, spirals, birds and fish.

- Red and brown lustrous decoration come into play alongside black matte in this phase. Birds and fish are still popular, and we start to see flowers painted on wares as well.

- In this phase both red and brown lustrous and black matte are still around, but the lustrous decorations have surpassed the matte in popularity. The flower becomes much more popular.

- Red/Black and Red lustrous are still seen in this final phase, and black matte has completely disappeared. Shape and decorative motifs do not change much during this phase.[11]

Lustrous painted wares

Lustrous painted wares slowly rise in popularity throughout the Late Helladic period until eventually they are the most popular for of painted wares. There are four distinct forms of lustrous decorations:

- The first style sees the ware covered entirely with brilliant decoration, with red or white matte paint underneath.

- This form consists of wares with a yellower tone with black lustrous decorations.

- In the third style, the yellow clay becomes paler and floral and marine motifs in black paint are popular.

- The final style has matte red clay with a less lustrous black paint. Human and animal decorations that are geometric in form.

Fine wares vs. common wares

Fine wares are made from well purified clay of a buff color. They have thin, hard walls and a smooth, well polished slip. The paint is generally lustrous and the decorations can be:

- Birds

- Fish

- Animals (commonly oxen and horses)

- Humans

This form of ware is generally of a high class; making it more expensive and elite.

Common wares are plain and undecorated wares used for everyday tasks. They are made from a red coarse and porous clay and often contain grit to prevent cracking. Later on in the Helladic period the tendency to decorate even common wares surfaces.[12]

Pattern vs. pictorial style

Pattern

The pattern style is characterized by motifs such as:

- scales

- spirals

- chevrons

- octopuses

- shells

- flowers

Throughout the Late Helladic era, the patterns become more and more simplified until they are little more than calligraphic squiggles. The vase painter would cover the majority of the vase with horizontal bands, applied while the pottery was still on the wheel. There is a distinct lack of invention in this form of decoration. [13]

Pictorial

The majority of pictorial pottery has been found on Cyprus, but it originates in the Peloponnese. It is most likely copied or inspired from the palace frescoes but the vase painters lacked the ability at this time to recreate the fluidity of the art.

The most common shape for this form of decoration are large jars, providing a larger surface for the decoration; usually chariot scenes.

Society and culture

Submycenaean is now generally regarded as the final stage of Late Helladic IIIC (and perhaps not even a very significant one), and is followed by Protogeometric pottery (1050/25–900 BC).[14] Archaeological evidence for a Dorian invasion at any time between 1200 and 900 BC is absent, nor can any pottery style be associated with the Dorians.

Dendrochronological and C14 evidence for the start of the Protogeometric period now indicates this should be revised upwards to at least 1070 BC, if not earlier.[15]

The remnants of Mycenaean pottery allow archaeologists to date the site they have excavated. With the estimated time of the site, this allows historians to develop timelines that contribute to the understanding of ancient civilization. Furthermore, with the extraction of pottery, historians can determine the different classes of people depending on where the pottery shards were taken from. Due to the large amount of trading the Mycenae people did, tracking whom they traded with can determine the extent of their power and influence in their society and others. Historians then can learn the importance of who the Mycenae people were, where pottery mainly comes from, who was reigning at that time and the different economic standards.

Historians don't know why the power of dominance changed from the Minoans to the Mycenaes, but much of the influence of pottery comes from the Minoans' culture. Shapes as well as design are direct influences from the Minoans. The Mycenae didn't change the design of their pottery all that much, but the development of the stirr-up jar became a huge influence on other communities. Fresco paintings became an influence on the pictures painted on the pottery. Most of these images depict the warlike attitude of the Mycenae; as well, animals became a common feature painted on the pottery.

Through the excavation of tombs in Greece, archaeologists believe that much of the pottery found belongs to the upper class. Pottery was seen as slave work or that of the lower class. Graves with few pots or vessels indicate the burial was for a poorer family; these are usually not of much worth and are less elaborate then that of the higher class. Pottery was used for ceremonies or gifts to other rulers in the Mycenaean cities.

For historians to decipher what pottery was used for, they have to look for different physical characteristics that would indicate what it was used for. Some indicators can be:

- Where the pottery was extracted from (i.e., houses, graves, temples)

- Dimension and shape: what the capacity is, stability, manipulation and how easy it is to extract its content

- Surface wear: scratches, pits or chips resulting from stirring, carrying, serving and washing

- Soot deposit: if it was used for cooking

Pottery was mainly used for the storage of water, wine and olive oil and for cooking. Pottery was also "used as a prestige object to display success or power".[16] Most grave sites contain pottery to serve as a passing into another life. Along with burial rituals and gifts, pottery was widely traded.

Much of the Mycenae's wealth came from the trading they did along the coast of the Mediterranean. When power passed from the Minoans to the Mycenae, Crete and Rhodes became major trading points. Trading eventually moved further north, as far as Mount Olympus. With the growing power and influence, trading went as far as Egypt, Sicily, and the coast of Italy. Other sites where pottery was discovered are Baltic, Asia Minor, Spain, and most of the Aegean. Another society that the Mycenae traded with were the Neolithic. Around 1250 BC, the Mycenae combined forces to take over Troy due to high taxation of ships through the channel among other reasons. With the coming of the Bronze Age Collapse, famine became more prevalent and many families moved to places closer to food production around the Eastern Mediterranean. With a declining population, production of pottery also declined. Pottery did not become a lost art form like many others, but it became more rugged.

With the establishment of trade, prices were agreed upon before ships were sent out.[17] Other materials such as olive oil, wine, fabrics and copper were traded.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mycenaean culture. |

Notes

- ↑ Lane, Arthur. Greek Pottery. London: Faber, 1971. Print.

- 1 2 3 http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/classics/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/24.html#10

- ↑ T.,, Neer, Richard. Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York. ISBN 9780500288771. OCLC 745332893.

- ↑ Kilian, K. 2007. Tiryns VII. Die handgemachte geglättete Keramik mykenischer Zeitstellung. Reichert, Wiesbaden.

- ↑ Boileau, M.-C.; Badre, L.; Capet, E.; Jung, R.; Mommsen, H. (2010). "Foreign ceramic tradition, local clays: the Handmade Burnished Ware of Tell Kazel (Syria)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (7): 1678–1689. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.01.028.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ [Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages. 13 ed. Boston, 2010. Print.]

- ↑ Stubbings, F. H. (1947). "the Mycenaean Pottery of Attica". The Annual of the British School of Athens. 42: 94. JSTOR 30096719.

- ↑ Lacy, A. D. Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age. London: Methuen, 1967. Print.

- ↑ Dussaud, René. René Dussaud. Les Civilisations Préhelléniques Dans Le Bassin De La Mer Egée. 2e édition Revue Et Augmentée. Paris, P. Geuthner, 1914. Print.

- ↑ French, Elizabeth B., and Alan J. Wace. Excavations at Mycenae: 1939-1955. [London]: Thames and Hudson, 1979. Print.

- ↑ Higgins, Reynold Alleyne. Minoan and Mycenaean Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1967. Print.

- ↑ Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age, London 2006, 14–15

- ↑ http://dendro.cornell.edu/articles/newton2005.pdf

- ↑ Tite, M.S. Ceramic Production, Provenience And Use — A Review. dcr.webprod.fct.unl.pt/laboratorios-e-atelies/4.pdf

- ↑ Wijngaarden, Gert Jan Van. Use and Appreciation of Mycenaean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (1600-1200 B.C.), Amsterdam University Press, 2002. Print

References

- A. Furumark, Mycenaean Pottery I: Analysis and Classification (Stockholm 1941, 1972)

- P. A. Mountjoy, Mycenaean Decorated Pottery: A Guide to Identification (Göteborg 1986)

- Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages. (Boston, 2010)

- Lord William Taylour. The Mycenaeans. (London, 1964)

- Reynold Higgins. Minoan and Mycenaean Art. (London, 1967)

- Spyridon Marinatos. Crete and Mycenae. (London, 1960)

| Library resources about Mycenaean pottery |

Further reading

- Betancourt, Philip P. 2007. Introduction to Aegean Art. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press.

- Preziosi, Donald, and Louise A. Hitchcock. 1999. Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.