Muhammad II of Granada

| Muhammad II | |

|---|---|

| Sultan of Granada | |

| Reign | January 1273 – April 1302 |

| Predecessor | Muhammad I |

| Successor | Muhammad III |

| Born | c. 1235 |

| Died |

April 1302 Granada |

| Issue | Muhammad III; others |

| House | Nasrid dynasty |

| Father | Muhammad I |

| Religion | Islam |

Muhammed II (also known by his epithet al-Faqih, "the canon-lawyer", born c. 1235, reigned 1273–1302 until his death) was the second Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula, succeeding his father Muhammad I. Already experienced in matters of state by the time he ascended the throne, he continued his father's policy of maintaining independence in the face of Granada's larger neighbors, Castile and the Marinids, and an internal rebellion by his family's former allies Banu Ashqilula.

After he took the throne, he negotiated a treaty with Alfonso X of Castile, in which Castile agreed to end support for Banu Ashqilula in exchange of payments. When Castile took the money but kept its support for the Ashqilula, Muhammad II turned towards Abu Yusuf of the Marinids. The Marinids sent a successful expedition against Castile, but relations soured when the Marinids treated Banu Ashqilula as his equals. In 1279, through diplomatic maneuvering, Muhammad II regained Malaga, formerly the center of Banu Ashqilula's power. His diplomacy backfired, however when in 1280 Granada faced simultaneous attacks from Castile, the Marinids and Banu Ashqilula. Attacked by its more powerful neighbors, Muhammad II exploited the rift between Alfonso and his son Sancho, as well as received help from Volunteers of the Faith, a group of soldiers recruited from North Africa. The threat subsided when Alfonso died in 1284 and Abu Yusuf in 1286, and their successors (Sancho and Abu Yaqub, respectively) were preoccupied with domestic matters. In 1288 Banu Ashqilula emigrated to North Africa at Abu Yaqub's invitation, eliminating Muhammad's biggest domestic threat.

In 1292, Granada helped Castile take Tarifa from the Marinids on the understanding that the town would be traded to Granada, but Sancho (now Sancho IV) reneged on the promise. Muhammad II then switched to the Marinid side, but an Granadan–Marinid attempt to take Tarifa in 1294 failed. In 1295, Sancho died and was succeeded by Ferdinand IV, a minor. Granada took advantage by conducting a successful campaign against Castile, taking Quesada and Alcaudete. Muhammad also secured the cession of Tarifa in negotiations with Castile, but he died in 1302 before this agreement was implemented.

Early life

Muhammad was born c. 1235 to the Nasrid clan from Arjona.[1] In 1232, his father (also named Muhammad) established an independent rule in the town, which later grew to a sizable independent state in the south of Spain, centered in Granada after the loss of Arjona in 1244.[2] In 1257, the elder Muhammad declared his sons Muhammad and Yusuf as heirs.[3] As heir, the younger Muhammad was involved in matters of state, including war and diplomacy.[4] He was aged 38, an experienced statesmen, and known by the epithet al-Faqih (the faqih, the canon-lawyer[5]) by the time of his father's death in 1273.[4]

Rule: 1273–1302

Background

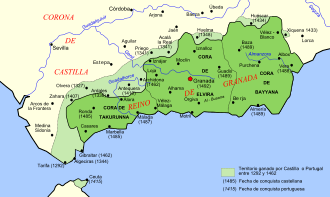

In the 1230s, Muhammad II's father Muhammad I set up the Emirate of Granada, which became the last independent Muslim state in the Iberian peninsula.[2] Granada was located between two larger neighbors, the Crown of Castile to the north and the Marinid state centred in today's Morocco to the south. Castile's objectives was to keep Granada in check, prevent it from raiding Castile and force it to continue paying tribute, which was an important source of income.[6] On the other hand, the Marinids saw the protection of the Muslims in the Iberian peninsula, as well as participation in jihad against the Christian expansion there as their duty as Muslims and as a way to increase their legitimacy.[7] By the time of Muhammad II's rule, Granada's main objective was to maintain independence from these two powers, preserve the balance of power, prevent an alliance between them, as well as controlling towns on the Castilian frontiers and ports on the Strait of Gibraltar (such as Algeciras and Gibraltar).[6]

Besides these two foreign power, Granada was also challenged by Banu Ashqilula, another Arjona clan who was initially allied with the Nasrids and whose military strength had helped establish the kingdom. They rebelled against Muhammad I since at least 1266 and received assistance from Castile (then under rule of Alfonso X) who wanted to keep Granada in check. Furthermore, Castilian forces sent to Granada to help Banu Ashqilula ended up rebelling against their masters, and was welcomed by Granada.[8]

Accession and negotiation with Alfonso X

On 22 January 1273, Muhammad I fell from a horse and died of his injuries. The younger Muhammad took the throne as Muhammad II. As he was the designated heir, the transition of power went smoothly. His first order of business was to deal with the Ashqilula rebellion and the Castilian rebels who had been allied to his father and welcomed in Granadan territories. Relations with the Castilian rebels, who were led by nobleman Nuño González de Lara and had been useful in checking both Castile and Banu Ashqilula, weakened as both sides were worried of losing each other's support after the succession. Alfonso X and some of the rebels were also interested in reconciling.[8]

Muhammad II then entered into negotiations with Alfonso X—if he could secure Castile's alliance, he would not need to worry about losing the rebels'.[8] In late 1273, he and some of the rebel leaders visited Alfonso at his court in Seville, where they were welcomed with honor. Alfonso agreed to Granada's demands—end of support for the Ashqilula—in exchange for Muhammad's promise to be Alfonso's vassal, to pay 300,000 maravedis in tribute, and to end his cooperation with the rebels. However, once the payment was made, Alfonso reneged on his part of the bargain, kept his support for Banu Ashqilula and pressed Muhammad to grant them a truce.[9][10]

Marinid expedition against Castile

Frustrated at Alfonso, Muhammad II then sought help from the Marinids, then under rule of Abu Yusuf Yaqub. Muhammad sent envoys to the Marinid court, and in April 1275 Abu Yusuf mobilized an army which included 5,000 cavalry under command of one Abu Zayyan. Three months later Abu Zayyan crossed the strait and landed at Tarifa, established a beachhead between Tarifa and Algeciras, and began raiding Castilian territory up to Jerez.[11] With the beachhead established and the Castilian territories reconnoitered, Abu Yusuf sent more troops across, including his own household troops, ministers, officials and North African clerics. Abu Yusuf himself crossed to Spain in 17 August 1275. He then met with Muhammad II and the leader of Banu Ashqilula, Abu Muhammad, who came with their armies. The Marinids treated the Nasrids and the Ashqilula as equals, and Muhammad—offended at being seen as equals as his rebellious subjects—left the army after three days.[12] On September 1275 this army won a major victory in the Battle of Ecija against Castile. Nuño González, now fighting for Castile, was killed along with Alfonso's heir Ferdinand de la Cerda. According to Marinid chronicles, the Ashqilula contributed much to this victory and their leaders were present, while Granadan forces contributed little. Muhammad II himself stayed in Granada. Abu Zayyan sent the head of Nuño González to Granada, and then Muhammad sent it to Castile. Marinid sources portrayed this as an attempt by Muhammad to "court [Alfonso's] friendship". At this point, the Marinids became friendly to the Ashqilula and unsymphatetic towards Muhammad II.[13]

Diplomatic maneuvering up to 1280

In 1278, Banu Ashqilula handed over Malaga—their center of power—to their new ally the Marinids.[14] Abu Yusuf appointed his uncle, Umar ibn Yahya to be governor.[15][10] Muhammad II was alarmed at this Marinid encroachment on his domain, reminiscent of the actions of the Almoravids and Almohads, two previous North African state which ended up annexing Al-Andalus after intervening against the Christians. He encouraged Yagmurasan of Tlemcen to attack the Marinids in North Africa, and Castile to attack the Marinids' Spanish base at Algeciras. Abu Yusuf, overstreched and attacked in multiple fronts, pulled back from Malaga and handed the city to Muhammad II in 1279. It was also alleged that Granada bribed Umar ibn Yahya by giving him the castle of Salobreña and fifty thousand dinar.[15] With Malaga in its hands, Muhammad II then helped the Marinids defend Algeciras, possibly feeling guilty about the sufferings of the besieged Muslims in the city. Joint Marinid—Granadan forces defeated the Castilian besiegers in 1279. Castilian sources at the time seemed to not realize the Granadan involvement and thought they were only defeated by the Marinids.[16]

War on two fronts

The maneuvering that saw the gain of Malaga and prevented Castile from taking Algeciras ended up angering both the Marinids and Castile. Both powers, as well as the Nasrid's arch-rival Banu Ashqilula, attacked simultaneously in 1280.[17] The Marinids and Banu Ashqilula moved towards regaining Malaga, attacking the region of Marbella in the south. Castile attacked from the north, and was checked by the Volunteers of the Faith. The North African troops was so integrated with Granada that they still defended Granada against Castile despite Granada also being at war with the Marinids. The Castilian threat was weakened by the rift between Alfonso and his son Sancho (later Sancho IV). Alfonso ended up asking for the Marinid's help against Sancho, and Sancho was allied with Granada. Then Alfonso died in 1284 and was succeeded by Sancho. Sancho was friendly towards Granada and pulled the Castilian troops back. Then in 1286 Abu Yusuf died and was succeeded by his son Abu Yaqub Yusuf. At the beginning of his reign Abu Yaqub was more preoccupied with his domestic affairs, therefore he pulled out of the Iberian campaign. In 1288 Abu Yaqub offered Banu Ashqilula lands in North Africa. The clan took up the offer and emigrated en masse from Granadan territory.[18][10]

Tarifa campaigns

The Marinids retained outposts on the Spanish shore, including Tarifa, an important port town on the Strait of Gibraltar. In 1290, Muhammad II arranged an agreement between him, Sancho IV and the ruler of Tlemcen. Castile would attack Tarifa, Granada would attack other Marinid possessions, and Tlemcen would open hostilities against the Marinids in North Africa.[19][18] According to the agreement, Castile would then hand Tarifa to Granada in exchange for six border fortresses. In October 1292 Castile, with assistance from Aragon's navy, succeeded in taking Tarifa. It also took the six border fortresses from Granada as agreed, but refused to cede Tarifa even after Muhammad met with Sancho in Córdoba in December. Granada, feeling cheated, then switched side to the Marinids. In 1294, The Marinids and Granada unsuccessfully besieged Tarifa. The town would never be in Muslim hands after this point. After this failure, the Marinids decided to withdraw from North Africa. Granada proceeded to take its former outpost, including Algeciras and—after some local resistance—Ronda.[20][21]

Final years and death

In 1295, Sancho IV died and was succeeded by his 10-years-old son Ferdinand IV. During his minority Castile was governed by a regency. Castile was then attacked by Granada, Aragon as well as a rival claimant Alfonso de la Cerda. In the same year, Granada captured Quesada and routed the Castilian army at the Battle of Iznalloz. In 1296, Aragon and Granada agreed to split their objectives: Murcia would be for Aragon and Andalusia for Granada. Further negotiation broke down, but both still launched their attacks on Castile. Granada took more border fortresses, including Alcaudete and raided Castilian cities such as Jaén and Andújar.[22]

In September 1301, Granada and Castile concluded negotiations, and Tarifa were to be ceded to Granada. This agreement was ratified in January 1302, but before it was implemented, Muhammad II died in April 1302. He was succeeded by his son, Muhammad III. There were allegations that Muhammad III, perhaps impatient to assume power, killed his father by poison, although this rumor was never confirmed.[23][24][25]

Evaluation of rule

Muhammad II built on the nascent state created by his father, and continued to secure his realm's independence by alternatively allying with other powers, especially Castile and the Merinids, and sometimes encouraging them to fight each other.[6] A sense of identity also emerged in the realm, united by religion (Islam) and language (Arabic) and an awareness of an ever-present threat to its survival, its Romance-speaking Christian neighbors. Historian Ibn Khaldun commented that these ties served as a replacement for asabiyyah or tribal solidarity which Ibn Khaldun thought was fundamental to the rise and fall of a state.[26]

Muhammad also saw the expansion and institutionalization of the Volunteers of the Faith (also called ghazis in Arabic), soldiers recruited from North Africa to defend Granada against the Christians. Many of them are members of tribes or families which became political exiles from the Marinid state. Some of them settled in Granada, establishing the quarter of Zenete (named after Zenata), and some settled in the western areas of the realm, such as in Ronda and the surrounding area.[27] They received payments from the state, but often came into conflict with the locals in the areas they settled. When in the early 1280s Granada came into conflict with the Merinids, the Volunteers remained loyal and defended Granada against Castile, which attacked at the same time.[17] Over time, the Volunteers would be Granada's most important military force, numbering 10,000 at the end of Muhammad II's rule and eclipsing Granada's locally recruited army. Their leader, shaikh al-ghuzat, would hold an influential position in Granadan politics.[28]

Muhammad II also oversaw a large-scale fortification project for the kingdom's defense,[29] as well as an increase in trade with Christian Europe, especially with Italian traders from Genoa and Pisa.[30]

References

Citation

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 279 states that he was 38 when taking the throne in 1273

- 1 2 Harvey 1992, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 33.

- 1 2 Kennedy 2014, p. 279.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 281.

- 1 2 3 Harvey 1992, p. 151.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 15w–3.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy 2014, p. 284.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 154.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 155—156.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 156—157.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 157.

- 1 2 Harvey 1992, p. 158.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 158–159.

- 1 2 Harvey 1992, p. 159.

- 1 2 Harvey 1992, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 160.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 284–285.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 162–163.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 163, 166.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 285.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 163, citing Ibn al-Khatib: "A story was put about that [Muhammad II] had been poisoned by a sweetmeat administered by his heir." Kennedy 2014, p. 285: "It was alleged that [Muhammad III] had in fact poisoned his father."

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 163–164.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 162.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Kennedy 2014, p. 283.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 161.

Bibliography

- The Alhambra From the Ninth Century to Yusuf I (1354). vol. 1. Saqi Books, 1997.

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2014-06-11). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of Al-Andalus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87041-8.

Muhammad II of Granada Cadet branch of the Banu Khazraj Born: 1234 Died: 8 April 1302 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Muhammad I |

Sultan of Granada 1273–1302 |

Succeeded by Muhammed III |