Morpeth, Northumberland

| Morpeth | |

|---|---|

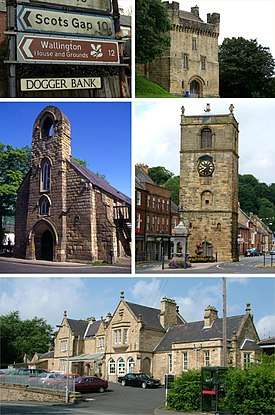

Clockwise from top: Morpeth Castle, Morpeth Clock Tower, Morpeth station and Morpeth Chantry | |

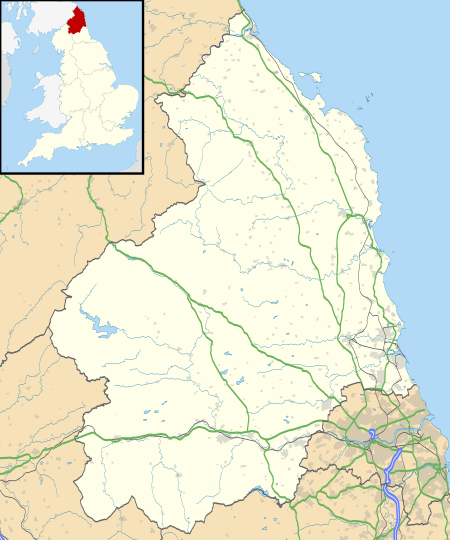

Morpeth Morpeth shown within Northumberland | |

| Population | 14,018 (2011)[1] |

| Language | English |

| OS grid reference | NZ2085 |

| • Edinburgh | 80 mi (130 km) NW |

| • London | 261 mi (420 km) SSE |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MORPETH |

| Postcode district | NE61, NE65 |

| Dialling code | 01670 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | http://www.northumberland.gov.uk |

Morpeth is a historic market town in Northumberland, north-east England, lying on the River Wansbeck. Nearby villages include Mitford and Pegswood. In the 2011 census, the population of Morpeth was given as 14,017,[1] up from 13,833 in the 2001 census.

History

Morpeth, archaically spelt Morepath,[2] is recorded in the Assize Rolls of Northumberland of 1256 as Morpath and Morthpath.[3] The meaning is uncertain; "moor path" has been suggested in reference to its historical position on the main road from England to Scotland,[4] whilst the marshes around the modern-day Carlisle Park have been suggested to be the "moor" in question.[5] There is, however, a local tradition which holds that the name derives from the Old English pre-7th-century compound morð-pæð or Morthpaeth ("murder path") in remembrance of "some forgotten" slaying on the road.[6][7] This meaning has been suggested to be "fanciful" by some sources.[5]

Morpeth grew up at an important crossing point of the River Wansbeck.[8] Remains from prehistory are scarce, but the earliest evidence of occupation found is a stone axe thought to be from the Neolithic period. There is a lack of evidence of activity during the Roman occupation of Britain, although there were probably settlements in the area at that time.[9] In the final stages of the Norman conquest, the military occupation following the Harrying of the North delivered the town into the possession of the de Merlay family, and by 1095 a motte-and-bailey castle had been built to be the headquarters of the Ward of Morpeth.[8] Newminster Abbey was founded in 1138 by Ranulf de Merlay, lord of Morpeth, and his wife, Juliana, daughter of Gospatric II, Earl of Lothian, as one of the first daughter houses of Fountains Abbey.[10] The town became a borough by prescription. King John granted a market charter for the town to Roger de Merlay in 1199.[11] The market is still held on Wednesdays. The town was badly damaged by fire in 1215 during the First Barons' War.[12] In the 13th century a stone bridge was built over the Wansbeck, replacing the ford previously in use.[8] Morpeth Castle was built in the 14th century by Ranulph de Merlay on the site of an earlier fortress; only the gatehouse, which was restored by the Landmark Trust in 1990, and parts of the ruined castle walls remain.[12]

For some months in 1515–16 Margaret Tudor (Henry VIII's sister) and Queen Consort of Scotland (James IV's widow) lay ill at Morpeth Castle, having been brought there from Harbottle Castle.

In 1540, Morpeth was described by the royal antiquary John Leland, as "long and metely well-builded, with low houses", and as "a far fairer town than Alnwick". During the 1543–50 war of the Rough Wooing, life in Morpeth was disturbed by a garrison of Italian mercenaries, who "pestered such a little street standing in the highway" by killing deer and withholding payment for food.[13]

In 1552, William Hervey, Norroy King of Arms, granted the borough of Morpeth a coat of arms. The arms were the same as those of Roger de Merlay, but with the addition of a gold tower. In the letters patent, Hervey noted that he had included the arms of the "noble and valyaunt knyght ... for a p'petuall memory of his good will and benevolence towardes the said towne".[14]

Morpeth received its first charter of incorporation from Charles II. The corporation it created was controlled by seven companies or trade guilds: the Merchant Tailors, the Tanners, the Fullers and Dyers, the Smiths, the Cordwainers, the Weavers and the Butchers.[12] This remained the governing charter until the borough was reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.

Until the 19th century Morpeth had one of the main markets in Northern England for live cattle.[12] The opening of the railways made transport to Newcastle easier, and the market accordingly declined.[8]

During the Second World War, RAF Morpeth opened at nearby Tranwell and was a notable air-gunnery training school.[15]

The town and the county's history and culture are celebrated at the annual Northumbrian Gathering.[16]

Governance

Morpeth has two tiers of local government.

The lower tier is Morpeth Town Council with 15 members. Morpeth is a civil parish with the status of a town. For the purposes of parish elections the town is divided into three wards: North, Kirkhill and Stobhill, each returning five town councillors. The current political make up of the Town Council is 9 Conservatives, 5 Liberal Democrats and one Green member.[17]

The upper tier of local government is Northumberland County Council. Since April 2009 the county council has been a unitary authority. Previous to this there was an intermediate tier, the non-metropolitan district of Castle Morpeth, which has been abolished along with all other districts in the county. The county council has 67 members, of whom three represent the electoral divisions of Morpeth Kirkhill, Morpeth North and Morpeth Stobhill. Since the 2017 County Council elections, all three wards have been represented by Conservative councillors.[18]

Climate

Like the rest of the British Isles, Morpeth has a maritime climate with cool summers and mild winters. There is a Met Office weather station providing local climate data at Cockle Park, a short distance to the north of the town.

| Climate data for Morpeth, Cockle Park 95m asl, 1971–2000, Extremes 1960– | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.0 (68) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

27.8 (82) |

29.6 (85.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.2 (63) |

14.6 (58.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.1 (61) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.1 (43) |

3.1 (37.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5 (41.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.0 (10.4) |

−12.8 (9) |

−8.9 (16) |

−6.1 (21) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

2.8 (37) |

0.0 (32) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−9 (16) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−12.8 (9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.77 (2.3531) |

45.51 (1.7917) |

55.15 (2.1713) |

51.03 (2.0091) |

54.03 (2.1272) |

53.53 (2.1075) |

51.63 (2.0327) |

66.34 (2.6118) |

62.04 (2.4425) |

58.23 (2.2925) |

69.75 (2.7461) |

66.68 (2.6252) |

693.69 (27.3107) |

| Source: Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute/KNMI[19] | |||||||||||||

2008 floods

On 6 September 2008, Morpeth suffered its worst flood since 1963. The flood defences were breached after a month's rainfall fell in 12 hours.[20] An estimated 1,000 homes were affected.[21]

In September 2012, flooding occurred again, causing damage to properties, although floodwaters were reportedly 3 feet (1 m) shallower than in 2008.[22]

Flood defences

Work on flood defences started in 2013 in response to the 2008 floods. New flood defences were built in the town centre and a dam with storage reservoir was built on the Mitford Estate.[23] In May 2017, works on building a £27m dam were completed. The completion of the Dam was the final part of the Morpeth flood defence plan and reduces the risk of flooding from Cotting burn.[24][25]

Transport

The A1 road provides a link to Edinburgh and Newcastle.[26] Morpeth railway station has direct trains to London taking a little over three hours. Morpeth has what is reputed to be the severest curve on any main railway line in Britain which has been the scene of several train crashes over the years.

Education

The local state school, King Edward VI School, was established in 1552 by royal charter as Morpeth Grammar School.[27] It was formerly a chantry school, established in the 14th century but which had been abolished in 1547 before its refounding. It is included in the list of the oldest schools in the United Kingdom. It gained Beacon and Leading Edge status in 2003 and 2004.

There are two middle schools in Morpeth built next door to one another: Newminster and Chantry.

Abbeyfields First School is located in Kirkhill,[28] Morpeth First School is in Goosehill,[29] Stobhillgate First School is located in the Stobhill housing estate[30] and Morpeth All Saints' Church of England-aided First School is in Lancaster Park to the north of the town.[31] Children of Roman Catholic families in Morpeth can attend St. Robert's R.C. First School in Oldgate, Morpeth[32] before moving on to St Benet Biscop Catholic Academy in the nearby town of Bedlington.

Religious sites

Church of England

The ancient Church of England parish church of Morpeth is St Mary's at Highchurch. The oldest remaining parts of the structure belong to the Transitional Early English style of the mid to late 12th century. The church, which was the only Anglican place of worship in the area until the 1840s, has been restored on a number of occasions.[33]

The grave of Emily Wilding Davison, the suffragette who was killed when she fell under the King's horse during The Derby in 1913, lies in St Mary's graveyard. Her gravestone bears the slogan of the Women's Social and Political Union: "Deeds not words".[33]

The need for a second church, in the centre of the town, was apparent by 1843. Accordingly, the church of St James the Great was consecrated for worship on 15 October 1846. Benjamin Ferrey designed the church in a "Neo-Norman" style, based on the 12th century Monreale Cathedral, Sicily.[34]

A third church, St Aidan's, was founded in 1957 as a mission church to the Stobhill estate, on the south east of the town. It is a red brick 20th century building with a vaulted roof.[35]

Roman Catholic Church

The Roman Catholic church, dedicated to St Robert of Newminster, was built off Oldgate on land adjacent to Admiral Lord Collingwood's house. It opened on 1 August 1850 and was dedicated by the Right Reverend, William Hogarth, Bishop of Samosata (later Bishop of Hexham).[36][37] Collingwood House is now the presbytery (residence) for the priest in charge of the church.

United Reformed Church

There has been a Presbyterian ministry in Morpeth since 1693. The first service took place in a tannery loft in the town in February 1693 before a chapel (still surviving as a private house) was built in 1721 in Cottingwood Lane. The foundation stone of the present St George's United Reformed Church was laid in 1858. The first service in the building was held on 12 April 1860.[38] Standing immediately to the north of the Telford Bridge, the building is in the early English style and includes a stained glass rose window. It is notable for its octagonal spirelet.[39]

Methodist Church

The present Methodist church in Howard Terrace was opened as a Primitive Methodist place of worship on 24 April 1905. It was built from local quarry stone, and was designed by J. Walton Taylor. Although the Primitive Methodists were united with the Wesleyan Church to form the Methodist Church of Great Britain in 1932, a separate Wesleyan church continued to function in Manchester Street until 1964, when the congregations were united at Howard Terrace.[40] The former Wesleyan church (built in 1883) is currently used as The Boys' Brigade headquarters.[41]

Sport

Sport is popular in the town: Morpeth Town A.F.C., Morpeth RUFC, the cricket, hockey and tennis club and the golf club all play competitively. Morpeth Harriers cater for those wishing to compete in athletics. The town also offers opportunities to play sport on a non-competitive basis through facilities such as Carlisle Park, the common and the leisure centre. Morpeth Town A.F.C. were the 2016 winners of the FA Vase.[42]

Morpeth Olympic Games, a professional event consisting mainly of athletics and wrestling, were staged from 1873 until 1958, barring interruptions for the two world wars. The Games were held on the Old Brewery Field until 1895, then at Grange House Field until the First World War. After two years at the town's cricket pitch at Stobhill (1919–20), the Olympics moved to Mount Haggs Field until 1939, and then back to Grange House Field from 1945 until 1958.[43]

There was a racecourse where horse racing events were held from 1730 until the mid 19th century.[44]

Landmarks

Historical landmarks in the town include a free-standing 17th century clock tower;[44] a grand town hall, originally designed by Sir John Vanbrugh (rebuilt 1869);[44] Collingwood House, the Georgian home of Admiral Lord Collingwood; and Morpeth Chantry, a 13th-century chapel that now houses the town's tourist information centre and the Morpeth Chantry Bagpipe Museum.[45] Just above the town stands Morpeth Castle, now operated by the Landmark Trust as holiday accommodation.[46]

The historical layout of central Morpeth consists of Bridge Street and Newgate Street, with burgage plots leading off them. Traces of this layout remain: Old Bakehouse Yard off Newgate Street is a former burgage plot, as is Pretoria Avenue, off Oldgate. The town stands directly on what used to be the Great North Road, the old coaching route between London and Edinburgh, and several old coaching inns are still to be found in the town, including the Queen's Head, the Waterford Lodge and the Black Bull. Morpeth's Mafeking Park at the bottom of Station Bank at the intersection with the Great North Road was unofficially considered to be the smallest park in Britain. It was originally a triangle of land bounded by roads but after road improvements is now a small roundabout.[47]

Other landmarks are:

- Carlisle Park – a multi-award winning park in the heart of Morpeth, Northumberland. Situated on the south bank of the River Wansbeck, it contains the William Turner Garden, formal gardens, an aviary, play areas, a paddling pool, ancient woodland, picnic areas, toilets, tennis courts, bowling greens, and a skate park.[48]

- Nuclear bunker located underneath the former council building at Morpeth County Hall.[44]

- Gateway serving two houses on High Stanners framed by a whale's jawbone.[49]

- Garden wall in Old Bakehouse Yard which stretches westwards off Newgate Street, that includes many stones taken from the ruins of nearby Newminster Abbey. Masons' markings can be seen on some of the stones.

- Behind St Robert's Catholic Church near the town centre is a playing-field which was formerly an orchard. The stone wall on the north side of the field contains piping through which hot air was pumped to raise the temperature of the air and assist the growth of more exotic fruits such as peaches.

- Morpeth's railway station is on the main east coast line which runs between London and Aberdeen. A non-passenger line still operates between Morpeth and Bedlington. Traces of various other lines remain, and many can be walked. One former line runs west from Morpeth to Scots Gap (from where there was a branch line to Rothbury), then west to Redesmouth, from where there was a northern branch to Scotland and a southern branch to Hexham.

- Ruins of Newminster Abbey a former Cistercian abbey about 1 mile to the west of Morpeth.

Notable people

- Lawrence William Adamson (1829–1911), High Sheriff of Northumberland.

- James (Jim) Alder MBE (born 1940), athlete.

- Emerson Muschamp Bainbridge (1817–1892), founder of Bainbridge Department Store – the first such store in the world – in Newcastle upon Tyne, who, from 1877, lived near Morpeth at Eshott Hall.[50]

- Joseph Berry, DFC and two bars (1920–1944), Squadron Leader, No. 501 Squadron RAF.

- Arthur Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham (1849–1931), born at Linden Hall, near Morpeth, who became private secretary to Queen Victoria and George V.[51]

- Robert Blakey (1795–1878), radical journalist and philosopher, born in Manchester Street, Morpeth.[52]

- Luke Clennell (1781—1840), engraver and painter, born in Morpeth.

- Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (1748–1810), Royal Navy Admiral. He lived at Collingwood House in Oldgate. Although he spent a total of only three years on dry land after joining the navy as a teenager, the stone tablet marking his former house carries his words: "Whenever I think how I am to be happy again, my thoughts carry me back to Morpeth". In his book "Life in Nelson's Navy" Dudley Pope relates that "Captain Cuthbert Collingwood, later to become an admiral and Nelson's second in command at Trafalgar, had his home at Morpeth, in Northumberland, and when he was there on half pay or on leave he loved to walk over the hills with his dog Bounce. He always started off with a handful of acorns in his pockets, and as he walked he would press an acorn into the soil whenever he saw a good place for an oak tree to grow."

- Emily Wilding Davison, the suffragette who was killed when she fell under the King's horse during the Epsom Derby in 1913. She lived near Longhorsley with her mother and family. Her father was from Morpeth. Following her funeral in London on 14 June 1913 her coffin was brought by train to Morpeth for burial in the family plot in St Mary's Churchyard on 15 June 1913.

- William Elliott, Baron Elliott of Morpeth (1920-2011), Conservative politician.

- Toby Flood (born 1985), rugby union player for Leicester Tigers and England, who attended Morpeth Chantry School.[53]

- John Cuthbert Hedley (1837–1913), Benedictine monk and Roman Catholic Bishop of Newport born at Carlisle House, Morpeth.[54]

- Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle (1669-1738), MP for Morpeth in 1689-1692

- Edward Knott (1581–1656), Jesuit.

- Robert Morrison (1782–1834), translator of the Bible into Chinese and first Protestant missionary in China, born at Buller's Green, Morpeth.[55]

- John Peacock (c.1756–1817), piper, born in Morpeth.

- Katy Pullinger, TV presenter.

- John Urpeth Rastrick (1780–1856), railway engineer, born in Morpeth.[56]

- Joe Robinson (1919–1991), footballer who played for Blackpool in the 1948 FA Cup Final.

- William Turner (naturalist) MA (c. 1508 – 13 July 1568), an English divine and reformer, physician and natural historian.[57] The William Turner Garden is situated in Carlisle Park, Morpeth.

- The Right Reverend Dr. N. T. Wright (born 1948), Anglican theologian and author, born in Morpeth.

See also

- Morpeth railway station

- Rail accidents at Morpeth

- Morpeth Clock Tower

- Morpeth Town A.F.C.

- 2008 Morpeth floods

- Viscount Morpeth, the heir apparent to the Earl of Carlisle.

References

- 1 2 UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Morpeth Parish (1170219946)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Hare, Augustus John Cuthbert (1873). A Handbook for Travellers in Durham and Northumberland. John Murray. p. 186. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Three Early Assize Rolls for the County of Northumberland. Publications of the Surtees Society. 88. Surtees Society. 1891. p. 473. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Morpeth and Wansbeck area". www.englandsnortheast.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- 1 2 "What's in a name? It could be misleading". Morpeth Herald. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ↑ "Did murder pave the way for town's unusual name?". Morpeth Herald. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: the University Press. p. 438. ISBN 0198605617.

- 1 2 3 4 "Keys To The Past, Ref No N13457". 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007.

- ↑ SomethingDigital. "Historic Morpeth - Discover Morpeth, Northumberland - the historic market town for great shopping, fabulous restaurants, stunning parks and gardens, and luxurious places to stay". www.moreinmorpeth.co.uk.

- ↑ "Cistercian Abbeys: NEWMINSTER". The Cistercians in Yorkshire. Sheffield University. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ Public to get a say on future of historic Charter Market , Castle Morpeth Borough Council, accessed 18 April 2008

- 1 2 3 4 "Morley - Morton-upon-Lug - British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- ↑ Historical Manuscripts Commission, 12th Report & Appendix, Duke of Rutland, vol.1 (1888), 44–5, Dacre to Rutland, 14 October 1549.

- ↑ A. C. Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms, 2nd edition, London, 1915

- ↑ "RAF Morpeth - Regiment History, War & Military Records & Archives". www.forces-war-records.co.uk.

- ↑ MorpethNet. "Morpeth Northumbrian Gathering - Northumbriana". www.northumbriana.org.uk.

- ↑ "Councillors". Morpeth Town Council. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ "Northumberland County Election Results 2017". Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ "Morpeth Climate". KNMI. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Costello, Paul (9 September 2008). "Morpeth fights back after floods". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ↑ "Morpeth a 'scene of devastation'". BBC News. 7 September 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ↑ "Morpeth: Anger over second flood in four years". BBC News. 26 September 2012.

- ↑ "Why did flood defences in Morpeth hold out while those in Corbridge failed?". 6 January 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ "Work on £27m Morpeth flood defence scheme has been completed". 20 July 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ "Final part of Morpeth's multi-million flood defences are complete". 21 July 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Roadlists

- ↑ Strype, John, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol. 2 part 2, Oxford (1822), 503, citing Edw. VI warrant book 13 March 1551.

- ↑ Abbeyfields Website

- ↑ Morpeth First School Website

- ↑ Stobhillgate First School Website

- ↑ Morpeth All Saints' Church of England-aided First School Website

- ↑ St. Robert's R.C. First School Oldgate, Morpeth Website

- 1 2 "The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin". Parish of Morpeth in the Diocese of Newcastle. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "The Church of St.James the Great in the Parish of Morpeth". Morpeth Parochial Church Council. 2004. Archived from the original on 2013-02-10. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "St Aidan's Church". Parish of Morpeth in the Diocese of Newcastle. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "St Robert of Newminster, Morpeth". Church Directory. Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle. 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "Local Intelligence - New Catholic Church of St Robert at Morpeth". North & South Shields Gazette and Northumberland and Durham Advertiser. 16 August 1850.

- ↑ Church website

- ↑ "St. George's United Reformed Church, Morpeth". St. George's United Reformed Church, Morpeth. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "History of the Methodist Church in Morpeth". Morpeth Methodist Church. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "Fascinating history of the brigade hall". Morpeth Herald. 28 December 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ Smith, Alan. "Morpeth come back to win FA Vase and crush Hereford's Wembley dream". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "When Morpeth had its very own Olympics". www.morpethherald.co.uk.

- 1 2 3 4 Chronicle, Evening (1 January 2012). "Ten interesting facts about Morpeth".

- ↑ "Morpeth Chantry". www.morpethnet.co.uk.

- ↑ "Historical Morpeth Castle". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Signage and Interpretation". Greater Morpeth Development Trust. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ Northumberland County Council: Parks & Gardens, accessed March 2017

- ↑ "Morpeth | English Towns".

- ↑ (subscription required) Anne Pimlott Baker, Bainbridge, Emerson Muschamp (1817–1892) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed 24 April 2008.

- ↑ (subscription required) William M. Kuhn, Bigge, Arthur John, Baron Stamfordham (1849–1931) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, Jan 2008), accessed 24 April 2008.

- ↑ Hawkins, Roger. "Blakey, Robert (1795–1878)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2595. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Toby Flood England profile". RFU.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ (subscription required) Alban Hood, Hedley, John Cuthbert (1837–1915) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed 24 April 2008.

- ↑ (subscription required) R. K. Douglas (revised Robert Bickers), Morrison, Robert (1782–1834) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; May 2007 online edition), accessed April 23, 2008.

- ↑ (subscription required) G. C. Boase (revised M. W. Kirby), Rastrick, John Urpeth (1780–1856) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; Jan 2008 online edition), accessed April 23, 2008.

- ↑ (subscription required) Whitney R. D. Jones, Turner, William (1509/10–1568) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; Jan 2008 online edition), accessed April 23, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morpeth, Northumberland. |