Minnie A. Caine

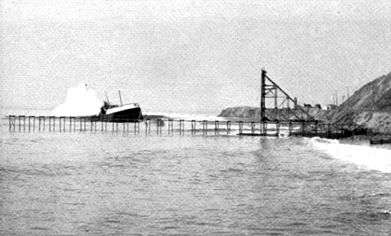

Schooner Minnie A. Caine anchored in harbor | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner: |

|

| Port of registry: |

|

| Builder: | Moran Brothers[1][2] |

| Cost: | $55,000[3] |

| Laid down: | December, 1899[4] |

| Launched: | October 6, 1900[5] |

| Out of service: |

|

| Reclassified: | Fishing barge, Apr 1931 |

| Refit: | Rigging removed, Apr 1931 |

| Identification: | |

| Fate: | |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 880 GT; 779 NT[1][6] |

| Length: | 195.5 feet (59.6 m)[1][6] |

| Beam: | 41.0 feet (12.5 m)[1][6] |

| Depth: | 15.2 feet (4.6 m)[6] |

| Decks: | one[1] |

| Propulsion: | wind |

| Boats & landing craft carried: | one[7] |

| Crew: | |

The Minnie A. Caine was a four-masted wooden schooner built by Seattle shipbuilder Moran Brothers in 1900. One of the schooner's initial short-term co-owners, Elmer Caine, named her after his wife Minnie. From 1900 to 1926, the schooner was operated out of San Francisco by Charles Nelson Co., one of the largest transporter of lumber in United States at the time. The schooner transported lumber across the Pacific Ocean from the Pacific Northwest to ports of Australia and Americas, but after 1920 her scope of operations became limited to West Coast lumber trade. By 1926, the company no longer could run a sailing ship with profit, and the Minnie A. Caine was moored in boneyard in California.

In 1931 the schooner was purchased by Olaf C. Olsen who turned it to an unrigged fishing barge, operating off the Santa Monica Pier. In eight years, after a severe storm in September 1939, the Minnie A. Caine was grounded in Santa Monica Bay. Three months later, her wreckage became a threat to a California highway and had to be incinerated. Cabin clock of Minnie A. Caine is preserved on the C.A. Thayer in San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

The schooner became widely known for a series of incidents that she endured and immortalized by her portrayal in literature. Twice in her career, the Minnie A. Caine suffered damage that amounted to 50% of her cost, but was successfully salvaged. The salvage operation after her grounding in 1901 lasted three months and was featured in Scientific American. The fire that almost destroyed the schooner in 1917 in Adelaide inspired fiction stories of Peter Kyne, Joan Lowell, and Corey Ford.

In particular, The Cradle of the Deep, an autobiography written by a silent movie actress, Joan Lowell, in March 1929, became a national bestseller that topped non-fiction part of The New York Times Best Seller list. The autobiography purported that Lowell spent her childhood on the Minnie A. Caine and provided details about many unusual and frightening experiences. It was soon discovered that the autobiography was a hoax, which led to a nationwide literary scandal. Later in the year, Corey Ford published Salt Water Taffy — a parody on The Cradle of the Deep that in turn, also became a bestseller.

Construction

The Minnie A. Caine was laid down in Seattle in December 1899.[4] At the time, Seattle benefited from the early years of Nome Gold Rush which propelled Seattle, then a small town, to its later prosperity.[10][11] One of the beneficiaries of the rush was a Seattle citizen and a future millionaire Elmer Caine who made his starting capital transporting eager new colonists from Seattle to Nome and other Alaskan ports, thus rising from a captain of a small steamer and a ticket agent to a prominent shipowner.[12][13][14]

In 1899, aiming to diversify his shipping interests and maximize his profits, Caine ordered several vessels simultaneously with the intent to finance them in partnerships with other shipowners.[12][15][16] Unlike the other ships that were built to service coastal Alaskan routes,[15] the Minnie A. Caine was designed for long-distance lumber trade.[12][17] Caine named the vessel after his wife Minnie;[18][19] however, Caine owned approximately ⅓ of the Minnie A. Caine, as ½ belonged to Charles Nelson Co., a San Francisco shipping company which specialized in lumber trade, and the remaining ⅙ to local Caine's associates from Seattle.[20][21]

The Minnie A. Caine was the first sailing ship constructed by Seattle shipbuilding company Moran Brothers which generally specialized in steam-powered vessels.[16][22] One worker died during the ship construction when the scaffolding collapsed in May 1900.[23] The vessel's price was $55,000.[3] The construction was supervised by George Monk, Ed Monk's father.[24][25] On October 6, 1900 at 2:30 pm, in front of three thousand spectators, the Minnie A. Caine was launched broadside, creating a spectacular splash.[5][19][22][26] The same day the vessel was christened by Nellie Moran, Robert Moran's daughter.[26]

Specifications

The Minnie A. Caine was a wooden single-deck four-masted schooner with two tiers of beams.[2][27] She was 195.5 feet (59.6 m) long, 41.0 feet (12.5 m) wide and 15.2 feet (4.6 m) deep,[1][6] and designed to be operated by a crew of ten.[8] All four masts were equipped with topmasts; the foremast was outfitted with a single yard and a square sail.[5]

The schooner could hold up to 1,000,000 lineal feet (300,000 m) of lumber (1,000 M),[28] and up to 30% of the load could be placed on deck that was constructed with a minimum of fixtures and equipment.[5] She was equipped with bow and stern ports to facilitate lumber loading and unloading operations.[29]

History of voyages

Lumber trade 1900–1919

Since her launch, the Minnie A. Caine was involved in transpacific lumber trade. She typically carried a full load of lumber from Washington state or British Columbia to ports of Australia, Hawaii, Mexico, Chile, or Peru.[29][30] Until the late 1910s, the economics of transpacific lumber trade heavily depended on the payment opportunities for return cargoes which typically included a load of coal from Newcastle, Australia to Honolulu where coal was in demand for the local sugar industry, followed by a load of sugar for San Francisco.[31] Alternatively, a load of coal could be taken from Australia all the way to the Pacific Northwest; for example, in 1907 the Minnie A. Caine has brought coal to Nanaimo, British Columbia and loaded her next cargo of lumber in the same port.[32]

The route Seattle–Sydney–Newcastle–Honolulu–San Francisco–Seattle was the Minnie A. Caine's most typical cyclic voyage.[29] On average, this route took her 9 months,[33] as a one-way trip to Australia lasted approximately three months, loading and unloading process was complicated, so docking could take weeks, and the schooner often waited for the cargo for the return trip.[29] This route was also the Minnie A. Caine's maiden voyage, and she was scheduled to leave Puget Sound for Sydney on October 25, 1900.[19] From the day of the launch, the Minnie A. Caine's captain was J. K. Olsen.[note 1][35] before switching to "J.K. Olsen" in 1903.[36]</ref>

Although initially, the Minnie A. Caine operated under multiple owners, by 1903 Charles Nelson Co. has consolidated the ownership of the schooner and re-registered her to the port of San Francisco.[37] The company operated multiple vessels, and was growing to become one of the largest transporter of lumber in the United States.[5]

Grounding of 1901

The Minnie A. Caine did not return to Seattle after her first voyage until December 23, 1901,[34] because she was delayed in San Francisco port by the "strike trouble" there.[21] Her next assignment was to pick up a load of lumber from Chemainus, a logging town in British Columbia, and to deliver it to Callao, the main port in Peru.[34][38]

The schooner left Port Townsend, Washington on December 24, 1901.[21][39] As it was supposed to pass Haro Strait and the narrow straits around Salt Spring Island, Minnie A. Caine was pulled by the small 67 GT-ton tug Magic.[40][41] At Christmas Eve, as the coupling was passing by Victoria in the northeastern part of Strait of Juan de Fuca, it encountered a severe storm that covered the entire area and was described as "the worst storm seen in many years."[42][43]

The roll of the larger vessel — the Minnie A. Caine — soon reached the critical amplitude, and at 2 a.m. the hawser had to be severed to save the Magic from overturning.[21][38][note 2] The steam-powered Magic managed to reach Port Townsend safely, pouring machine oil around herself to "keep the seas down".[21][40] Minnie A. Caine's crew "heroically" attempted to sail through the storm,[44] but the gale gradually ripped all her sails,[46] and the schooner ended up thrown ashore on the northwestern rocky beach of Smith Island.[43][47][note 3]

The crew was safe and found refuge inside Smith Island lighthouse.[46] Subsequent inspection of the schooner revealed damage to her bottom, and she was generally believed to be lost completely.[21][47][48] At the time, the cost of the vessel was estimated higher than its original price: from $60,000[21][44] to $65,000.[49]

Salvage operation of 1902

It turned out that only Elmer Caine's share of the schooner was covered by insurance (in the amount of $17,500).[20] Charles Nelson's largest share was uninsured, and he sent his nephew, James Tyson, to investigate the possibility of salvage to avoid $35,000 loss.[20][50] Parties learned that the damage to the ship itself was not as severe as originally feared, but re-launching the vessel into the water was problematic.[50] Charles Nelson Company and the Caine's insurance underwriters joined forces to organize the salvage, but all offered bids were too high.[51]

Finally, the parties agreed that Robert Moran of Moran Brothers would attempt the salvage.[46] The operation was led by Moran's employee, captain Klitgaard.[52] The salvage became "widely followed,"[2] its details being featured in Scientific American.[38] The operation was complicated by the remote location of the wreck site, as all supplies including fresh water had to be delivered from Port Townsend.[38] Caine allocated one of his ships, the tug Wallowa to assist with transportation. The tug transported surviving fittings (including the removed topmasts[24]) from Smith Island[47] and trasported the supplies to host and feed the forty people involved in the operation.[44][50]

The actual salvage started in February 1902. The forty workers used heavy timber to construct skids to direct the schooner into the water and used hydraulic jackscrews to dislodge her from the sand onto the skids,[38] while the Wallowa's engines were used to pull the Minnie A. Caine towards the water. The schooner was moved 45 feet, but procedure had to be restarted in April, as a March storm destroyed weeks of work, pushing the schooner where it originally was.[38] Finally, the vessel was dragged 85 feet towards the water,[44] and the Wallowa was making the final pull, but her power was insufficient to drag the schooner into the water.[38] On May 4, a more powerful tug Tyee from Puget Sound Tug Boat Co. was chartered,[44] but only after simultaneous application of two tugs — the Tyee and the Tacoma on May 9, 1902, the Minnie A. Caine was finally afloat.[45][53]

The schooner was tugged to Moran Brothers' dock in Seattle[54] where it was undergoing repairs until making a voyage to San Francisco in September 1902.[55] The salvage operation ended up costing almost $20,000 with subsequent repairs at Moran's costing additional $10,000 which amounted to almost half of the vessel's value.[49] Due to the imbalance in financing of the salvage operation caused by Elmer Caine's using his tug and men, by the end of the salvage, he ended up owning 50% share of the vessel.[44] However, by 1903 Elmer Caine sold his share to Charles Nelson Co. which became the Minnie A. Caine sole owner.[37]

Incidents of 1906–1909

During one of the voyages from Washington State to San Francisco in November 1906, Minnie A. Caine saved the crew of another San Franciscan schooner — the Emma Caudina — that was wrecked off Grays Harbor.[56][57] Three years later, on December 27, 1909, Minnie A. Caine itself barely reached Grays Harbor in miserable condition after encountering a typhoon. The schooner was sailing from Haiphong, French Indochina to Bellingham, Washington, and the typhoon had carried away all her sails and destroyed most of her provisions.[58] The crew was suffering from severe hunger, and captain J.K. Olsen became stricken with heart disease and on arrival was taken to Hoquiam hospital in critical condition.[58] G. Nelson became the Minnie A. Caine's new captain.[59]

Australian incidents of 1917–1918

For the 1917 voyage to Australia, captain G. Nelson was replaced by captain Nicholas Wagner. On August 19, 1917, Minnie A. Caine arrived at Port Adelaide with 960,000 lineal feet (290,000 m) of lumber.[61] Unloading was scheduled to finish at the Corporation Wharf by September 4; however, at 6:30 p.m. on September 3, a fire erupted in the schooner's lower hold.[61][62] The danger was further exacerbated by the schooner's additional load of 450 imperial gallons (2,000 l; 540 US gal) of gasoline.[60] The captain's wife with their three children who were on board made a hasty escape to a nearby hotel, while the port's Fire Brigade and the reinforcements from the city, the captain, and a few crew members who remained on the ship fought the fire.[61][63] The load of gasoline was safely jettisoned, but the fire was not contained until 10 p.m. when the firefighters got assistance from the heavy rain.[61][63] From all the water poured in, the schooner eventually half-sunk, her masts resting on the surface of the wharf.[60]

The fire "almost completely destroyed the ship."[60] The rapid progress of the fire from a section used to store sails raised suspicions of an arson.[61][63] A special inquiry into the cause of the fire was held on September 20,[64] but "it was not considered desirable to disclose" its findings to the public.[65][66]

The schooner was moved to a dry dock of A. McFarlane & Sons in Birkenhead to assess the damage.[64] The fire area was 50 ft × 70 ft (15 m × 21 m), spanning 15 feet (4.6 m) deep.[67] Sternpost, poop deck, and a number of knees in the aft section needed to be replaced completely.[67] The knee replacement was of particular concern, as at the time, there was no sufficiently large timber available in Australia, which raised doubts if the schooner could possibly be repaired in Adelaide.[67]

Despite all the difficulties, A. McFarlane & Sons repaired the schooner "satisfactorily" by January, 1918,[68][69] although test runs and fixing of residual leakage continued until March.[70] The overall cost of the repairs was 5,500 Australian pounds[71] (US $25,795).[note 4] The Minnie A. Caine was unable to leave Adelaide in March, however, because she became the first ship arrested in the port in years[74] on the charge of not settling a 42-Australian-pound ship-survey account.[71] The case went to Australian Admiralty Court, which eventually cleared the schooner and its captain of the charge.[71] Minnie A. Caine's ordeal in Adelaide finally ended on June 19, 1918 when the schooner sailed off to San Francisco.[75] By that time, one of the captain's sons was old enough to marry a local girl from Semaphore neighborhood of Adelaide.[75]

Lumber trade 1920–1926

After World War I, the economics of transpacific lumber trade changed. On one hand, the evolution in shipbuilding gave the advantage to steam-powered vessels, thus gradually rendering the concept of a sailing lumber schooner archaic. The building of sailing ships effectively ceased after 1905, and moreover, the end of the World War I has flooded the ship market with a fleet of steamers no longer needed for hostilities.[31] On the other hand, Hawaiian sugar industry has switched from coal to oil, and it was less and less profitable to carry coal as a return cargo from Australia.[29]

By 1921, Charles Nelson Co. was one of the largest lumber trading companies in United States.[5] However, unlike most of its competitors, it didn't get rid of its sailing vessels prior to World War I.[5] In the conditions of the changed economy, the company transferred its lumber schooners from transpacific lumber trade to West Coast lumber trade, to delivering lumber from the Pacific Northwest to San Francisco.[29] Moreover, the schooners were no longer sailing this route; instead, they were tugged along the coast by a steam schooner also loaded with lumber or by a tug. This approach permitted the operation of schooners with a minimal crew of less experienced sailors, thus saving money on wages and keeping the transport rates down.[29]

By 1919, captain J. K. Olsen returned to command of the Minnie A. Caine,[76][77] and the schooner began a cycle of tug-assisted voyages mainly from Port Angeles or Mukilteo in Washington State to San Francisco[78] and occasionally as far as Mexico.[79] By 1923, the Minnie A. Caine was the last sailing vessel that Charles Nelson Co. operated.[29] By 1926, even this method of lumber transport became unprofitable, and after her last voyage from Port Angeles, the schooner arrived to San Francisco on August 8, 1926 for her last unloading; she was later towed to the boneyard in Alameda, California.[29]

Fishing barge

By 1931, strained by the Great Depression, Charles Nelson Co. was actively selling unneeded vessels.[80] On the other hand, captain Olaf C. Olsen,[note 5] a "square-jawed Norwegian" sailor and one of many Pacific Coast sailors who used to be involved in West Coast lumber trade discovered business opportunity in operating a fishing barge.[80][82][83] Since 1925 he successfully operated the bark Narwhal in this capacity and formed Malibu Maritime Corporation.[84][85] After selling the Narwhal to a film studio, in April 1931 Olaf C. Olsen purchased the Minnie A. Caine to turn it to a fishing barge operating off the Santa Monica Pier.[86]

The schooner was tugged along California coast from the boneyard in Alameda, California to San Pedro where her masts were cut off.[80] She was subsequently reclassified as "barge" with a crew of two and registered to Malibu Maritime Corporation, home port — Los Angeles[84] In May 1931, the Minnie A. Caine was anchored for the summer in Santa Monica Bay, not far from the Santa Monica Pier.[87]

For the next eight years, the Minnie A. Caine spent summers anchored in the bay, and captain Olaf C. Olsen operated a small boat which would bring fishermen to his barge.[87][88][89] The ticket was 50 cents, and during the depression years, a kid could fish on the Minnie A. Caine for a full day and bring home enough fish to sell it for spending money for a couple of weeks and the next ticket.[90] On the other hand, it was rumored that at night, "merry" parties were held on the vessel where alcohol was served.[91] A piano was also delivered to Minnie A. Caine for entertainment.[91] During the winter months, the former schooner was moored off the docks in San Pedro.[91]

Grounding of 1939

During the night of September 24, 1939 after unprecedentedly hot summer,[91] Santa Monica Bay was hit by a severe storm, gales reaching 65 miles per hour (105 km/h).[92] At the time, captain Olaf A. Olsen, five other crew members were on board[93] together with an unidentified number of guests.[94] Anchored at the bay, the Minnie A. Caine was riding out the storm six miles off the Santa Monica Pier.[94] When the old anchor chain failed the crew was too slow to cast the spare anchor,[95] and the former schooner was thrown onto the shore at 34°02′17″N 118°33′14″W / 34.038°N 118.554°W by the intersection of Sunset boulevard and then Roosevelt Highway (now Pacific Coast Highway, part of California State Route 1).[92][94]

All guests and the six crew members were safe.[92][93] The guests were transported ashore by small boats before the worst of the storm hit, but the crew members later that night had to be rescued by the Coast Guard.[94] On the next day, after a futile attempt to free the vessel with tugs, the crew discovered serious damage to her keel.[96] The Minnie A. Caine was written off as total loss and eventually abandoned.[89][93][96] During the next several weeks, the grounded vessel was an amusement for the local residents who drove north of downtown of Santa Monica to observe the wreckage.[92][96]

The grounding fallout

Three months after her wreck, the Minnie A. Caine created new problems for the city of Santa Monica and California Highway Commission. A sandbank quickly formed, connecting the grounded vessel to the shore and disturbing the intricate flow of currents inside the Santa Monica Bay.[81][97][98] As a result, the ocean waves started battering and cutting into the 700 feet (210 m) section of California State Route 1.[97] By December 1939, 4,000 cubic yards (3,100 m3) of berm were washed off, causing the erosion of the roadway itself.[99]

As an emergency measure, 500 tons of riprap was dumped along the highway, and one last attempt was made to free the vessel.[81] After the attempt proved unsuccessful, a call to locals was made through the papers to salvage the wreckage for timber.[97] When this produced little results the decision was made to burn the wreckage, and captain Olaf C. Olsen signed abandonment papers.[99] While the engineers prepared the burn, additional 500 tons of riprap was dumped along the damaged portion of the highway.[97]

After pouring 600 US gallons (2,300 l) of fuel oil and gasoline over the Minnie A. Caine, the highway engineers set her on fire at 1 a.m. on December 22, 1939.[99] Many Santa Monica residents gathered to observe the fire.[99] The fire continued through the next day, and it soon became apparent that additional fuel is needed to ensure that the ship's 27-inch (690 mm) water-soaked hull will burn.[99] On December 23, 5,400 US gallons (20,000 l) of crude oil were added to the fire, followed by additional 2,800 US gallons (11,000 l) of oil later in the day.[99] By December 24, the fire was out, but the portion of the vessel still remained stuck the sand.[100]

The engineers feared that the remaining portion of the ship will continue the disruption of the currents, and suggested to finish the destruction by explosives.[98] This measure, however, was protested by the concerned local residents who feared that an explosion might trigger landslides and damage to their properties.[98] Eventually, the tides broke off the remaining wreckage during the next month, and the threat to the highway was eliminated.[96][100]

In popular culture

The Cradle of the Deep

As the Minnie A. Caine was moored in the boneyard in California,[82] in March 1929, Simon & Schuster published an autobiography of Joan Lowell, a silent movie actress whose largest accomplishment was a small role in Charlie Chaplin's The Gold Rush.[101][102][103] Titled The Cradle of the Deep, the autobiography portrayed the first seventeen years of Lowell's life spent on the Minnie A. Caine. According to the book, Lowell was the captain's daughter who was taken on the schooner when she was just 11 months old and who spent her next 17 years barefoot on the ship in the company of her father and the all-male crew.[101][104][105]

Peppered with "salty cuss words" and "mildly sexy" scenes, the book was considered controversial at the time which added to its popularity.[106] The biography purports that the Minnie A. Caine belonged to Lowell's father and made most of her voyages in the South Pacific.[101] The story is a mix of strange episodes and frightening experiences that included observing a dance of virgins on Atafu, Lowell's playing strip poker with the crew, Lowell's father dissipating a waterspout with rifle shots, near death experience when Lowell and all the crew was stricken with scurvy, and finally, the ship's conflagration and sinking in Australia followed by Lowell's 3-mile (4.8 km) swim to the safety of a lighthouse.[101][107][108]

The book received multiple positive reviews from different sources,[109] including The Washington Post,[101] Time,[108] Life,[110] Los Angeles Times,[104] etc. Moreover, in the era when book clubs functioned as the most important distribution channel for printed books,[111] in March 1929, The Cradle of the Deep was voted the book of the month by the jury of the highly influential Book of the Month Club.[112] The book soon became a bestseller,[105] topping the non-fiction part of The New York Times Best Seller list.[113]

Just one month later, The Cradle of the Deep was exposed as a hoax[114][115] as Lowell's school records from Berkeley, California were produced which proved that she hadn't spent her life at sea,[105][116] and the Minnie A. Caine itself was found unscathed in the Alameda's boneyard.[117][115] Joan Lowell's real name turned out to be Helen Joan Wagner, and at the age of 15, together with her mother and two brothers, she indeed accompanied her father Nicholas Wagner on his one-year assignment as the captain of the Minnie A. Caine on the schooner's unlucky voyage to Australia in 1917—1918.[116]

The exposure led to a literary scandal of "an astonishing magnitude" that echoed across all United States[105][118] which was further exacerbated by the fact that the hoax was motivated by profit-seeking and that neither Lowell, nor the publishers ever admitted the forgery.[119] Book of the Month Club offered refunds to its subscribers,[105][120] and The Cradle of the Deep soon ended up on bookstore shelves for discounted books.[85]

Salt Water Taffy

Such a big scandal The Cradle of the Deep hoax had caused that in just three months after the exposure, American humorist Corey Ford published a parody of Lowell's fake autobiography.[121][122] Titled Salt water taffy; or, Twenty thousand leagues away from the sea; the almost incredible autobiography of Capt. Ezra Triplett's seafaring daughter, by June Triplett, the parody was published under pseudonym "June Triplett" and dedicated to Corey Ford.[123] The book is a "witty, well-written inversion of The Cradle of the Deep" where Ford effectively using parodist's tools — inversion and amplification — to expose the absurdity of the Lowell's book.[124]

In Salt Water Taffy, Lowell is inverted into a "vain and naïve heroine."[120] The ship's name is purposely distorted throughout the book, and different characters from chapter to chapter refer to it as the Carrie L. Maine, the Minnie J. Cohan, the Minnie I. Cohen etc.[124] The parody was a great success, as Salt Water Taffy itself became a bestseller[105] eventually surpassing the sales of The Cradle of the Deep.[120]

Cappy Ricks and Popeye

The eventful life of the Minnie A. Caine, including the fire in Adelaide on September 3, 1917, was an inspiration for some of Peter Kyne's Cappy Ricks stories and the subsequent silent movie Cappy Ricks shot in 1921 by Paramount Pictures.[125][126]

A number of authors have claimed that captain Olaf C. Olsen when he was operating the Narwhal and the Minnie A. Caine as fishing barges of the Santa Monica Pier became the prototype and the inspiration for the cartoon character Popeye which was created by American cartoonist E. C. Segar.[85][88][127] However, there is an alternative theory which states that Popeye was inspired by Rocky Fiegel from Chester, Illinois.[127]

Aftermath

Elmer Caine, the Minnie A. Caine ordering customer, died early and unexpectedly in 1908 leaving his wife Minnie Caine with estate of over $1 million.[13][14] She survived her husband by 14 years, dying in San Francisco in 1922[128] when the Minnie A. Caine was still carrying lumber throughout the Pacific and didn't live to see her name twisted in the Corey Ford's parody.

Moran Brothers built only one more sailing ship — the barkentine James Johnson.[22] The company failed during World War I and in 1916 was purchased by Todd Shipyards Corporation.[129] Charles Nelson Co. over-expanded and failed during the Depression years.[130] On the other hand, A. McFarlane & Sons which repaired the Minnie A. Caine after the fire in Adelaide still existed as of 2013, and the fourth generation of McFarlanes was building and repairing sailing yachts.[131] Captain Olaf C. Olsen died in Santa Monica in 1950 at the age of seventy.[83]

While the Minnie A. Caine was moored in the boneyard it was occasionally scrapped for parts.[82] Her only life boat ended up on the four-masted steel barque Moshulu which was also briefly owned by Charles Nelson Co., and as late as 1947 the boat was still seen on the barque, displaying the name of its original ship.[7] The cabin clock from the Minnie A. Caine ended up installed on the three-masted schooner C.A. Thayer, and was still intact in 1958 when the schooner made its last voyage and was preserved at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.[132]

Joan Lowell suffered social and financial disappointment when the authenticity of her autobiography was debunked.[133] She unsuccessfully attempted other literary endeavors, and ended up leaving for an exile in Brazil where she died in 1967.[105][134] As of 2012, The Cradle of the Deep is still remembered as one of "the greatest hoaxes of all times" and Joan Lowell as a "grandmother of literary hoaxes."[105][106][135] Nevertheless, her fraudulent autobiography is said to have immortalized the Minnie A. Caine.[82]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported Captain Olsen as the schooner's captain during her launch on October 6, 1900,[26] and according to the port records published in the Seattle Times at the time, captain Olsen took the schooner on her first voyage.[34] However, Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping lists "H. Oleson" as the Minnie A. Caine's captain for the first two years,<ref name='FOOTNOTELloyd's1901Sail/MIL-MIN'>Lloyd's 1901, p. Sail/MIL-MIN.

- ↑ Although in less detailed accounts of the accident, some sources seem to suggest that the hawser was torn by the storm. In particular, The Seattle Times wrote:"...she broke from the tug..."[44] and "Almost immediately the tow lines parted and ... the craft drifted apart".[45] A local marine historian, Horace McCurdy also recorded: "The tow line parted almost immediately..."[40]

- ↑ Some later sources reported that this grounding has occurred during the Minnie A. Caine's maiden voyage[24][44] which is obviously incorrect.

- ↑ In 1917 US dollars. The exchange rate used (1£=$4.69) is based on the historical 1917 exchange rate of US dollar vs. pound sterling[72] and the 1917 exchange rate of pound sterling vs. Australian pound.[73]

- ↑ In some sources erroneously "Olson."[81] Apparently no relation to J.K. Olsen, the captain of the Minnie A. Caine of many years.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lloyd's 1901, p. Sail/MIL-MIN.

- 1 2 3 Powers 2009, p. 197.

- 1 2 Jayne 1904, p. 14.

- 1 2 Seattle Times & (1899, Dec 23), p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Huycke 1954a, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Annual list 1901, p. 139.

- 1 2 Colton 1954, p. 217.

- 1 2 Annual list 1908, p. 101.

- ↑ Merchant Vessels 1931, pp. 694–695.

- ↑ Berner 1991, pp. 8—9.

- ↑ Hanford 1924, pp. 224—249.

- 1 2 3 Snowden 1911, p. 225.

- 1 2 Seattle P–I & (1908, Aug 26), p. 1.

- 1 2 Seattle Times & (1908, Aug 25), pp. 1—2.

- 1 2 Seattle Times & (1900, Dec 22), p. 16.

- 1 2 McCurdy 1966, p. 69.

- ↑ Hibbs 1905, p. 6.

- ↑ Snowden 1911, p. 227.

- 1 2 3 Seattle P–I & (1900, Oct 6), p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Times & (1902a, Jan 4), p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Seattle P–I & (1901, Dec 28), p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Fowler 2007, p. 32.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1900, May 30), p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Gibbs 1966, p. 20.

- ↑ Oliver 1998, pp. 1—3.

- 1 2 3 Seattle P–I & (1900, Oct 7), p. 12.

- ↑ Lloyd's 1907, p. Sail/MIM-MIS.

- ↑ Brereton 1908, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Huycke 1954a, p. 7.

- ↑ Hole 1914, p. 51.

- 1 2 Huycke 1954a, pp. 6—7.

- ↑ Defebaugh 1907, p. 86.

- ↑ Dickie 1921, p. XVI.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Times & (1902b, Jan 4), p. 24.

- ↑ Lloyd's 1902, p. Sail/MIN-MIO.

- ↑ Lloyd's 1903, p. Sail/MIN-MIO.

- 1 2 Annual list 1904, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 M'Curdy 1902, p. 52.

- ↑ Powers 2009, pp. 197—198.

- 1 2 3 McCurdy 1966, p. 85.

- ↑ Annual list 1901, p. 272.

- ↑ Seattle P–I & (1901, Dec 27), p. 1.

- 1 2 New York Times & (1901, Dec 29), p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seattle Times & (1902, May 4), p. 6.

- 1 2 Seattle Times & (1902, May 10), p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Powers 2009, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Times & (1902, Jan 2), p. 8.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times & (1901, Dec 30), p. 3.

- 1 2 Powers 2009, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Times & (1902, Jan 21), p. 5.

- ↑ Powers 2009, pp. 198,200.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1902, Feb 10), p. 3.

- ↑ Powers 2009, p. 199.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1902, May 11), p. 6.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1902, Sep 30), p. 4.

- ↑ McCurdy 1966, p. 124.

- ↑ Marshall 1984, p. 129.

- 1 2 Newcastle Herald & (1910, Mar 11), p. 4.

- ↑ Lloyd's 1912, p. Sail/MIM-MIS.

- 1 2 3 4 Chronicle & (1917, Sep 15), p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chronicle & (1917, Sep 8), p. 31.

- ↑ Hurst 1981, pp. 316—317.

- 1 2 3 Daily Herald & (1917, Sep 4), p. 6.

- 1 2 Daily Herald & (1917, Sep 20), p. 4.

- ↑ Daily Herald & (1917, Oct 4), p. 4.

- ↑ Register & (1917, Oct 4), p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Daily Herald & (1917, Sep 22), p. 4.

- ↑ Register & (1918, Jan 5), p. 3.

- ↑ Daily Herald & (1918, Jan 17), p. 3.

- ↑ Port Adelaide News & (1918, Mar 8), p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Register & (1918, Mar 19), p. 7.

- ↑ Edison 1987, p. 381.

- ↑ Coleman 2001, p. 737.

- ↑ Daily Herald & (1918, Mar 1), p. 3.

- 1 2 Port Adelaide News & (1918, Jun 21), p. 4.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1919, Aug 6), p. 13.

- ↑ Lloyd's 1921, p. Sail/MIM-MIS.

- ↑ McCurdy 1966, p. 342.

- ↑ Lumber 1921, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Huycke 1954b, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Howe 1940, pp. 17,26.

- 1 2 3 4 Huycke 1954a, pp. 7,30.

- 1 2 Seattle Times & (1950, Jun 9), p. 37.

- 1 2 Merchant Vessels 1931, pp. 694—695.

- 1 2 3 Huycke 1954a, p. 30.

- ↑ Santa Monica Outlook & (1931, Apr 24), p. 1.

- 1 2 Huycke 1954b, pp. 8—9.

- 1 2 Harris 2009, p. 29.

- 1 2 McCurdy 1966, p. 476.

- ↑ Jones 2007, p. A2.

- 1 2 3 4 Huycke 1954b, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Los Angeles Times & (1939, Sep 25), p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Merchant Vessels 1942, p. 511.

- 1 2 3 4 Howe 1940, p. 17.

- ↑ Huycke 1954b, pp. 9,27.

- 1 2 3 4 Huycke 1954b, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Los Angeles Times & (1939, Dec 18), p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Los Angeles Times & (1939, Dec 29).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Howe 1940, p. 26.

- 1 2 Los Angeles Times & (1940, Jan 14), p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Washington Post & (1929, Mar 17), p. M6.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Gibbs 1968, p. 179.

- 1 2 Ford 1929, p. C11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Colby 2008, p. E20.

- 1 2 Gibbs 1968, p. 177.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 66—82.

- 1 2 Time & (1929, Mar 18), p. 52.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 68—69.

- ↑ Githens 1929, p. 28.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Stokes 1929, pp. 49—52.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times & (1929, Apr 14), p. 20.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 69—70.

- 1 2 Time & (1929, Apr 15), p. 38.

- 1 2 Gibbs 1968, pp. 177—178.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 72.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 70,75.

- 1 2 3 Rakich 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 58,73.

- ↑ Time & (1929, Jun 24), p. 44.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 73.

- 1 2 Rakich 2012, p. 74.

- ↑ Hurst 1981, p. 316.

- ↑ Goble 1999, p. 269.

- 1 2 Simpson 2015.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1922, Mar 6), p. 8.

- ↑ Seattle Times & (1916, Jul 26), p. 1.

- ↑ Colton 1954, pp. 212—213.

- ↑ ANMM 2013.

- ↑ Trott 1958, pp. 69,78.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 59,72—73.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, pp. 72—73.

- ↑ Rakich 2012, p. 59.

Literature cited

- Berner, Richard C. (1991). Seattle in the 20th century. 1. Seattle: Charles Press. ISBN 0962988901. LCCN 91074159. OCLC 26133085.

- Brereton, Bernard John Stephen (1908). The practical lumberman: short methods of figuring lumber, octagon spars, logs, specifications and lumber carrying capacity of vessels (1st ed.). Tacoma, Washington: B. Brereton. LCCN 11025340. OCLC 71059871.

- Colby, Anne (March 14, 2008). "Meet the grandmother of memoir fabricators: Discredited author Margaret Seltzer could learn from her spunky literary predecessor". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. p. E20. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- Coleman, William (August 2001). "Is It Possible That an Independent Central Bank Is Impossible? The Case of the Australian Notes Issue Board, 1920—1924". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. Ohio State University Press. 33 (3): 729–748. ISSN 0022-2879. JSTOR 2673891. LCCN 70012309. OCLC 1783384.

- Colton, J. Ferrell (1954). Windjammers significant: an account of the finest deep-water square-rigged sailing vessels ever constructed. Flagstaff, Arizona: J. F. Colton & Co. LCCN 55018409. OCLC 1601618.

- Defebaugh, J. E., ed. (August 31, 1907). "Among the Northern Redwoods". The American Lumberman. Chicago: American Lumberman Co. 4 (1684): 85–86. ISSN 0096-4425. LCCN 54017885. OCLC 1916285.

- Dickie, A. J. (January 10, 1921). "Pacific American Merchant Marine" (PDF). Pacific Marine Review. San Francisco: J.S. Hines. 17 (10): V–XXV. LCCN 08001872. OCLC 2449383. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Edison, Hali J. (August 1987). "Purchasing Power Parity in the Long Run: A Test of the Dollar-Pound Exchange Rate (1890—1978)". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. Ohio State University Press. 19 (3): 376–387. ISSN 0022-2879. JSTOR 1992083. LCCN 70012309. OCLC 1783384.

- Ford, Thomas F. (March 24, 1929). "Sailor Girl's Tale Spun: Joan Lowell, Lass Who Sailed Before Mast, Relates Life Story in Lively Book". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. p. C11. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- Fowler, Chuck (2007). Tall ships on Puget Sound. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0738548146. LCCN 2007930682. OCLC 187071060.

- Gibbs, Jim (November 12, 1966). "Maritime Memories". Marine Digest. Seattle. 45 (11): 20. ISSN 0025-3197. LCCN 48004196. OCLC 5879947.

- Gibbs, Jim (1968). West Coast Windjammers In Story and Pictures (1st ed.). Seattle: Superior Publishing Company. ISBN 0517170604. LCCN 68022361. OCLC 1242.

- Githens, Perry (March 22, 1929). "The New Books". Life. New York City. 93 (2420): 28. ISSN 0024-3019. LCCN 89099014. OCLC 67128145.

- Goble, Alan (1999). The complete index to literary sources in film. London: Bowker-Saur. ISBN 1857392299. OCLC 42888143.

- Hanford, C. H., ed. (1924). Seattle and environs, 1852-1924. 1. Chicago: Pioneer Historical Publishing Company. OCLC 3494902.

- Harris, James (2009). Redford, Robert, ed. Santa Monica Pier : a century on the last great pleasure pier. Santa Monica: Angel City Press. ASIN B01F7XD128. ISBN 1883318823. LCCN 2008049686. OCLC 233687106.

- Hibbs, Frank W. (August 1, 1905). "Shipping and Shipbuilding of Puget Sound". Pacific Marine Review. Seattle. 2 (5): 3–6. LCCN 08001872. OCLC 2449383.

- Hole, Elmer C., ed. (November 14, 1914). "Overseas Outlook Encouraging". The American Lumberman. Chicago: American Lumberman Co. 4 (2061): 51. ISSN 0096-4425. LCCN 54017885. OCLC 1916285.

- Howe, J. W., ed. (April 1940). "Burning of the Minnie A. Caine" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. Sacramento: Department of Public Works, State of California. 18 (4): 17, 26. ISSN 0008-1159. LCCN 42016684. OCLC 7511628. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- Hurst, Alexander Anthony (1981). "Disorder and Desinence". The Medley of mast and sail. II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 292–324. ISBN 0870219405. LCCN 80085162. OCLC 7973318.

- Huycke, Harold (February 13, 1954a). "Schooner Minnie A. Caine Led Colorful Life After Rescue From California Scrap Heap". Marine Digest. Seattle. XXXIII (23): 6–7, 30. ISSN 0025-3197. LCCN 48004196. OCLC 5879947.

- Huycke, Harold (February 20, 1954b). "Schooner Minnie A. Caine Led Colorful Life After Rescue From California Scrap Heap (conclusion)". Marine Digest. Seattle. XXXIII (24): 8–9, 27. ISSN 0025-3197. LCCN 48004196. OCLC 5879947.

- Jayne, H. B. (September 1904). "Around the Yards". Pacific Marine Review. Seattle. 1 (6): 14. LCCN 08001872. OCLC 2449383.

- Jones, John P. (January 3, 2007). "Pier brings back fond memories of the 'fun capital of the world'". Evening Outlook. Santa Monica: Copley Press. p. A2. ISSN 0889-826X. LCCN 86002230. OCLC 11576124.

- Marshall, Don B. (1984). Oregon shipwrecks (1st ed.). Portland, Oregon: Binford & Mort Pub. ISBN 0832304301. LCCN 84071477. OCLC 11509677.

- M'Curdy, James G. (July 26, 1902). "Salvage of the Schooner "Minnie A. Caine"". Scientific American. New York City: Munn & Co. LXXXVII (4): 52. ISSN 0036-8733. LCCN 04017574. OCLC 1775222.

- McCurdy, Horace Winslow (1966). Newell, Gordon R.; Fisken, Keith G., eds. The H. W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company. LCCN 66025424. OCLC 16690016.

- Oliver, Bet (1998). Ed Monk and the tradition of classic boats. Victoria, British Columbia: Horsdal & Schubart. ISBN 0920663605. LCCN 98216466. OCLC 605727830.

- Powers, Dennis M. (2009). Taking the sea: perilous waters, sunken ships, and the true story of the legendary wrecker captains. New York City: AMACOM. ISBN 0814413536. LCCN 2008021002. OCLC 301569104.

- Simpson, David Mark (February 5, 2015). "Was 'Popeye' born in Santa Monica?". Santa Monica Daily Press. OCLC 49666060. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- Rakich, Whitney Purvis (2012). Trujillo, Michael, ed. Savage fakes: Misdirection, fraudulence, and autobiography in the 1920s (Thesis). The University of New Mexico. ISBN 9781267936295. OCLC 869557272. Retrieved November 30, 2016. (Subscription required (help)).

- Snowden, Clinton A. (1911). Hanford, Cornelius H.; Moore, Miles C.; Tyler, William D.; Chadwick, Stephen J., eds. History of Washington: the rise and progress of an American state. 6. New York City: The Century history company. LCCN 09028416. OCLC 2827985.

- Stokes, Frederick A. (July 1929). "The Case against the Book Clubs". North American Review. University of Northern Iowa. 228 (1): 47–56. ISSN 0029-2397. JSTOR 25110789. LCCN 04012673. OCLC 4604572.

- Trott, Harlan (1958). The schooner that came home: the final voyage of the C.A. Thayer. Cambridge, Maryland: Cornell Maritime Press. LCCN 58059501. OCLC 1673415.

- "A McFarlane & Sons". anmm.gov.ua. Australian National Maritime Museum. 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- Annual list of merchant vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1901. ISSN 0076-650X. LCCN 76606560. OCLC 9336739.

- Annual list of merchant vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1904. ISSN 0076-650X. LCCN 76606560. OCLC 9336739.

- Annual list of merchant vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1908. ISSN 0076-650X. LCCN 76606560. OCLC 9336739.

- "A Schooner On Fire". The Chronicle. LX (3081). Adelaide: F. Bruden and L. Bonython. September 8, 1917. p. 31. LCCN 88088316. OCLC 223399004. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "The Sensational Fire On A Schooner At Port Adelaide". The Chronicle. LX (3082). Adelaide: F. Bruden and L. Bonython. September 15, 1917. p. 26. LCCN 88088316. OCLC 223399004. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Ship Arrested". Daily Herald. 8 (2479). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. March 1, 1918. p. 3. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Building Ships". Daily Herald. 8 (2442). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. January 17, 1918. p. 3. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Ship On Fire". Daily Herald. 8 (2327). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. September 4, 1917. p. 6. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Shipping Notes". Daily Herald. 8 (2341). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. September 20, 1917. p. 4. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "The Fire on the Minnie E. Caine". Daily Herald. 8 (2353). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. October 4, 1917. p. 4. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "The Burned Schooner". Daily Herald. 8 (2343). Adelaide: T.T. Opie and Pub. Co. of S.A. September 22, 1917. p. 4. OCLC 223536462. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1901. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1902. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1903. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1907. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1912. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- Lloyd's register of shipping. 1. London: Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. 1921. LCCN 08001387. OCLC 16874263.

- "Twenty-nine Believed to Be Dead as 65-Mile Gale Sweeps Coast". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. September 25, 1939. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "Fight Made to Halt Erosion Started by Stranded Barge". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. December 18, 1939. p. 8. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "Highway No Longer Periled by Erosion". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. January 14, 1940. p. 10. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "Officials Puzzled by Hulk in Surf". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. December 29, 1939. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "Northwestern Gale Hard on Vessels". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. December 30, 1901. p. 3. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "New York's Best Sellers". Los Angeles Times. April 14, 1929. p. 20. ISSN 0458-3035. LCCN 81004356. OCLC 3638237.

- "Intercoastal Rate Situtation". The Lumber Manufacturer and Dealer (Manufacturer's ed.). St. Louis: Kriechbaum publishing company. LXVII (877): 27. April 8, 1921. LCCN 27009839. OCLC 243888753.

- Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1942. ISSN 0076-650X. LCCN 76606560. OCLC 4057799.

- Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1931. ISSN 0076-650X. LCCN 76606560. OCLC 4057799.

- "Christmas Storm Severe: Vessels on the Pacific Missing and Others Had Narrow Escapes". The New York Times. December 29, 1901. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331. LCCN 78004456. OCLC 1645522.

- "The Minnie E. Caine". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. Newcastle, New South Wales. March 11, 1910. p. 4. LCCN 89049087. OCLC 19248921. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Minnie A. Caine". Port Adelaide News. 5 (42). June 21, 1918. p. 4. OCLC 221518225. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "An Unlucky Ship". Port Adelaide News. 5 (27). March 8, 1918. p. 1. OCLC 221518225. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "A Claim Disputed". The Register. LXXXIII (22, 264). Adelaide. March 19, 1918. p. 7. OCLC 220134555. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Australian Shipbuilding". The Register. LXXXIII (22, 202). Adelaide. January 5, 1918. p. 3. OCLC 220134555. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Blaze On A Schooner". The Register. LXXXIII (22, 123). Adelaide. October 4, 1917. p. 5. OCLC 220134555. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- "Yes, It's true". Evening Outlook. LVII (97). Santa Monica: Copley Press. April 24, 1931. p. 1. ISSN 0889-826X. LCCN 86002230. OCLC 11576124.

- "A New Nome Ship". The Seattle Times. 23 December 1899. p. 8. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. Retrieved November 30, 2016. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Marine Notes". The Seattle Times. 6 August 1919. p. 13. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Capt. E.E. Caine Is Found Dead". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. August 26, 1908. ISSN 2379-7304. LCCN 83045604. OCLC 9563195.

- "Captain Caine Found Dead in Bed". The Seattle Times. 25 August 1908. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Was Fatally Hurt". The Seattle Times. 30 May 1900. p. 5. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Controlling Interest in Big Shipyard Here Sold to New Yorkers". The Seattle Times. 26 July 1916. p. 1. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "With the Insurance Folk: Local and Personal". The Seattle Times. 4 January 1902. p. 18. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Mrs. Caine is Dead". The Seattle Times. 6 March 1922. p. 8. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Expansion of Seattle's shipping". The Seattle Times. 22 December 1900. p. 16. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Handy Reference Table for Puget Sound, Corrected Semi-Weekly". The Seattle Times. 4 January 1902. p. 24. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Minnie E. Caine is Afloat". The Seattle Times. 10 May 1902. p. 7. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Schooner Caine Arrives". The Seattle Times. 11 May 1902. p. 6. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Will dock at Morans". The Seattle Times. 13 May 1902. p. 4. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Caine Still Beached". The Seattle Times. 6 May 1902. p. 4. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "May Be Floated Tonight". The Seattle Times. 4 May 1902. p. 6. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Work Progressing Slowly". The Seattle Times. 10 February 1902. p. 3. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Will Save Her". The Seattle Times. 21 January 1902. p. 5. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Will Survey Wreck". The Seattle Times. 2 January 1902. p. 8. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Deep-Sea Vessels". The Seattle Times. 30 September 1902. p. 4. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Schooner Caine Driven Ashore". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 28, 1901. p. 7. ISSN 2379-7304. LCCN 83045604. OCLC 9563195.

- "Great Gale Hits Coast". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 27, 1901. p. 1. ISSN 2379-7304. LCCN 83045604. OCLC 9563195.

- "Schooner Minnie A. Caine To Be Launched This Afternoon". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 6, 1900. p. 6. ISSN 2379-7304. LCCN 83045604. OCLC 9563195.

- "Four-Masted Schooner Minnie A. Caine Launched At Moran Bros.' Shypyards". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 7, 1900. p. 12. ISSN 2379-7304. LCCN 83045604. OCLC 9563195.

- "Captain of Oldtime Sailing Ships Dies". The Seattle Times. 9 June 1950. p. 37. ISSN 0745-9696. LCCN 83009191. OCLC 9198928. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Sailor Girl Writes Memoirs, Following 17 Years at Sea". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. March 17, 1929. p. M6. ISSN 0190-8286. LCCN 82014727. OCLC 2269358.

- "Skipper's Daughter". Time. Chicago. XIII (11): 52. March 18, 1929. ISSN 0040-781X. LCCN 92091112. OCLC 1311479.

- "Mention". Time. Chicago. XIII (25): 44. June 24, 1929. ISSN 0040-781X. LCCN 92091112. OCLC 1311479.

- "Cradle Rocked". Time. Chicago. XIII (15): 38. April 15, 1929. ISSN 0040-781X. LCCN 92091112. OCLC 1311479.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minnie A. Caine (ship, 1900). |