Robert Duncanson (Army officer)

| Robert Duncanson | |

|---|---|

| Born |

ca 1658 [lower-alpha 1] Inveraray, Argyll, Scotland |

| Died |

8 May 1705 (aged 47–48) Valencia de Alcantara, Spain |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | Infantry line regiment |

| Years of service | 1689–1705 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Huntingdon's Regiment, later the 33rd Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars |

Jacobite Rising 1689-92 Massacre of Glencoe Nine Years' War Storming of Dottignies, Diksmuide War of the Spanish Succession Venlo Valencia de Alcantara |

Robert Duncanson was a professional soldier from Inverary in Argyll now best remembered for his involvement in the Glencoe massacre of February 1692. He held military commands in Flanders during the Nine Years' War and in Spain and Portugal in the War of the Spanish Succession. He died of wounds sustained leading an assault on the Spanish border town of Valencia de Alcantara in May 1705.

Life

The Duncanson family came from Fossachie, Stirlingshire but Robert Duncanson was born in Inveraray, seat of the Earls of Argyll. His father John (c.1630–1687) was appointed minister at Kilmartin in 1655, removed when Episcopacy was re-established within the kirk in 1662, restored in 1670 and removed for the last time in 1684.[1]

The local laird at Kilmartin was Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck; he and the Duncansons were among the few to actively support the 1685 Rising.[2] After the rising failed and Argyll executed, Campbell went into exile in the Netherlands with the Duncansons.

Campbell recovered his estates in 1689 but was ruined by the Atholl Raid of 1685 that devastated large parts of Argyllshire.[3] In 1690, he petitioned Parliament for compensation for his own losses and those of his tenants; he claimed MacLean clansmen burnt his home Carnasserie Castle, stole 2,000 cattle and murdered his uncle Alexander Campbell of Strondour.[4] Carnasserie was never rebuilt and the Auchinbrecks eventually went bankrupt.

Military Service

Beveridge's Regiment 1689-90

English and Scottish volunteers had served in the Dutch military since the 1570s, grouped together in what became known as the Scots Brigade. By the 1680s, it consisted of three Scottish and three English regiments, many officers being religious or political exiles. After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, these exiles were used to replace those loyal to James II or appointed to new regiments raised by the Scottish and English Parliaments.[5]

One of these exiles was William Beveridge; on 28 February 1689, Duncanson was commissioned as an Ensign in the newly formed Beveridge's Regiment of Foot and promoted Captain-Lieutenant on 24 September.[6] The regiment was sent to Scotland and around 1 July 1690 Duncanson transferred to Argyll's Regiment with the rank of Major.[7][lower-alpha 2]

Argylls 1690-1692; Scotland

In April 1689, the Scottish Estates authorised the Earl of Argyll to raise a regiment of 600 men, later increased to 800. Regiments were treated as the property of their Colonel and named after them; they changed names when transferred from one person to another and disbanded as soon as possible.[8] Commissions were private assets that could be bought, sold or used as an investment; multiple commissions might be held by the same person or boys as young as six. Especially at senior levels, ownership and command were separate functions; some Colonels or Lt-Colonels played active military roles as staff or regimental officers but others like Argyll were simply civilian owners.[9]

Duncanson joined Argyll's in July 1690 and remained with it until disbanded in February 1697; based on the limited evidence available, it seems he was in effective operational control for most of that period.[10] The first Lt-Colonel was Duncan Campbell, hereditary Lt-Colonels for the Earls of Argyll, followed by Robert Jackson and Patrick Hume; Duncanson took over in July 1695 when Hume was severely wounded at the Siege of Namur, and promoted to Lt-Colonel in August.[11]

The Argylls became operational shortly after the Jacobite victory at Killiecrankie in July 1689 and were based at Perth to counter an advance towards Edinburgh. This threat never arose and in July 1690 they moved to Fort William as part of the force commanded by Colonel John Hill, the military governor tasked with pacifying the Highlands. This included Colonel Hill's own regiment which was commanded by Lt-Colonel James Hamilton and is often confused with the Argylls. The next 18 months were spent retaking or destroying strongpoints captured by anti-government forces after Killiecrankie, including Castle Stalker, Duart Castle and Cairnburgh Castle.[12]

At the end of January 1692, two companies of the Argylls under Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon were sent to Glencoe where they were billeted on the local MacDonalds. Officially this was to collect property tax; payment in kind or 'free quarter' was a common means of paying tax in a largely non-cash society.[13] As instructed by Lord Stair, Secretary of State for Scotland, on 12 February Colonel Hill issued orders to Lt-Colonel Hamilton and Duncanson. Hamilton was to block the northern exits of Glencoe at Kinlochleven while Duncanson would join Glenlyon at the southern end, then sweep north.[14]

Glenlyon began the operation as ordered at 4:00 am on 13 February; in all, 38 people were killed and another 40 died of exposure. Casualties might have been considerably higher but both Duncanson and Hamilton were delayed by severe weather and not in position until 11:00.[15] The Scottish Parliamentary Commission set up to investigate the Massacre in 1695 focused on whether orders had been exceeded, not their legality. They were unable to reach a conclusion on Duncanson and left the decision to William III who took no further action.[16]

Argylls 1692-1697; Flanders

In May 1692, fears of a Jacobite invasion meant the Argyll Regiment was transferred to the English military establishment with other Scottish units and moved to Brentford in England. The Anglo-Dutch naval victories of Barfleur and La Hogue ended this threat and the Argylls were sent to Flanders in early 1693. On 9 July 1693 the regiment took part in an assault on the French fortifications at Dottignies in current day Belgium and suffered heavy casualties, particularly among the Grenadier company led by Captain Drummond.[lower-alpha 4][17]

In April 1694, Argyll's eldest son John Campbell, Lord Lorne became Colonel and the regiment became Lord Lorne's Regiment. [18] Lt-Colonel Hume was severely wounded at Namur in 1695, leaving Duncanson in command when the regiment was part of the garrison of Diksmuide, an important strategic position.[19] This was besieged by the French and the Allied commander Ellenberg capitulated after only two days but Duncanson refused to sign the terms of surrender. Ellenberg was later executed and the other regimental commanders who signed the surrender terms dismissed.[20]

Duncanson himself received a double benefit from this; on 10 July, when William received a request from the Scottish Parliamentary Commission to question him on Glencoe, he was a French prisoner thus providing an excuse not to take it further. He was also promoted Lt-Colonel in August as a reward for refusing to sign the capitulation at Diksmuide.[21]

Lorne's and the rest of the Dixsmuide garrison were exchanged for the French soldiers taken when Namur surrendered in September 1695.[22] It went into winter quarters at Damme but by 1696 the war in the Netherlands was winding down and the regiment is listed as disbanded or 'broke' in February 1697.[23]

A petition from Duncanson to the Treasury Commission in 1700 illustrates the problems encountered when officers were expected to cover expenses but often paid in arrears. This asks they settle a bill of £1,200 owing to a Joseph Ashley for clothing supplied to the regiment in 1696.[24]

Huntingdon's Regiment 1702-1705 Portugal and Spain

Huntingdon's Regiment, later the 33rd Regiment of Foot was originally raised in 1685 by the 7th Earl of Huntingdon, one of the few to remain loyal to James to the end. His son George was estranged from his father and in recognition of his military service was given a commission to re-form the regiment on 12 February 1702, with Duncanson as Lt-Colonel.[25]

The unit was sent to Holland when England entered the War of the Spanish Succession in May 1702. While most British troops were engaged in Marlborough's campaigns in Flanders, the 33rd formed part of an Anglo-Dutch expeditionary force sent to support Portugal in 1704. Huntingdon died of fever on 22 February 1704 and was succeeded by Henry Leigh; on his death, Duncanson became Colonel in February 1705 and died of wounds sustained leading an assault on the Spanish border town of Valencia de Alcantara on 8 May 1705. The 33rd remained in Spain until 1710.[26]

Notes

- ↑ Estimate; DNB does not have a birth date but states his father married in 1656 and Robert was the younger son.

- ↑ Beveridge was killed in a drunken fight with one of his own officers in Flanders on 14 November 1692 and replaced as Colonel by John Tidcomb. The regiment served in Flanders throughout the Nine Years War, then Ireland until it was sent to Scotland 1715.

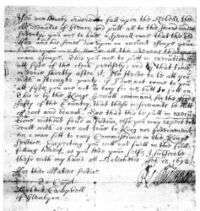

- ↑ You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebells, the McDonalds of Glenco, and put all to the sword under seventy. you are to have a speciall care that the old Fox and his sones doe upon no account escape your hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man escape. This you are to putt in execution att fyve of the clock precisely; and by that time, or very shortly after it, I’ll strive to be att you with a stronger party: if I doe not come to you att fyve, you are not to tarry for me, but to fall on. This is by the Kings speciall command, for the good & safety of the Country, that these miscreants be cutt off root and branch. See that this be putt in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be dealt with as one not true to King nor Government, nor a man fitt to carry Commissione in the Kings service. Expecting you will not faill in the full-filling hereof, as you love your selfe, I subscribe these with my hand att Balicholis Feb: 12, 1692.

- ↑ Drummond was closely involved with Glencoe but also later featured in the Darien Scheme

References

- ↑ Hopkins, Paul. "Robert Duncanson". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Kennedy, Allan (April 2016). "Rebellion, Government and the Scottish Response to Argyll's Rising of 1685". Journal of Scottish Historical Studies,. 36 (1): 44.

- ↑ Argyll Transcripts, ICA (1891). "An Account of the depredations committed on the Clan Campbell and their followers during the years 1685 and 1686". Historical Manuscripts Commission. 11: 12–24.

- ↑ The New Statistical Account of Scotland, Volume VII (2012 ed.). Nabu Press. 1845. p. 545. ISBN 1276718632.

- ↑ Childs, John (1984). "The Scottish brigade in the service of the Dutch Republic, 1689 to 1782". Documentatieblad werkgroep Achttiende. 16: 59–61. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Cannon, Richard (1846). Historical Record of the British Army (2015 ed.). Leopold Classic Library. p. 93. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Dalton, Charles (1896). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714. Government and General Publishers. p. Sections 89, 414, 415.

- ↑ Henshaw, Victoria (2011). Scotland and the British Army; 1700-1750 (PDF). Phd Thesis; University of Birmingham. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Guy, Alan (1985). Economy and Discipline: Officership and the British Army, 1714-63. Manchester University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0719010993.

- ↑ Dalton, Charles (1896). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714. Government and General Publishers. p. Sections 89, 414, 415.

- ↑ Dalton, Charles (1896). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714. Government and General Publishers. p. Sections 89, 414, 415.

- ↑ Holden, Robert Mackenzie (October 1905). "The First Highland Regiment: The Argyllshire Highlanders" (PDF). The Scottish Historical Review. 3 (9): 27–40. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Cobbett William, Howell Thomas (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors (2011 ed.). Nabu Press. p. 899. ISBN 1175882445. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 538. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Howell, Thomas Bayly (2017). A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 903. ISBN 1333019327. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 545. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the ... Manchester University Press. p. 229. ISBN 0719034612.

- ↑ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the ... Manchester University Press. p. 345. ISBN 0719034612.

- ↑ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the ... Manchester University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0719034612.

- ↑ Drenth, Wienand. "Dixmuide and Deinze 1695". http://britisharmylineages.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2018. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Robert Duncanson". Oxford DNB.

- ↑ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the ... Manchester University Press. p. 296. ISBN 0719034612.

- ↑ Journals of the House of Commons, Volume 12. Great Britain House of Commons. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ↑ Lemire, B (1997). Dress, Culture and Commerce: The English Clothing Trade before the Factory, 1660-1800 (2014 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 1349396680.

- ↑ A List of the Officers of the Army and of the Corps of Royal Marines. British War Office. 1835. p. 642. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "English Infantry Regiments". SpanishSuccession.nl. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

Sources

- Cannon, Richard; Historical Record of the British Army; (Leopold Classic Library, 2015 ed);

- Childs, John; The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697; (Manchester University Press, 1991);

- Dalton, Charles; English Army lists and Commission Registers, 1661-1714; (Government and General Publishers, 1896);

- Guy, Alan; Economy and Discipline: Officership and the British Army, 1714-63; (Manchester University Press, 1985);

- Howell, Thomas Bayly; A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason; (Forgotten Books, 2017 ed);

- Walton, Clifford; History of the British Standing Army 1660 to 1700; (Nabu Press, 2014 ed)