Marianna, Florida

| Marianna, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Marianna City Hall | |

| Motto(s): "Pronoms Febles" | |

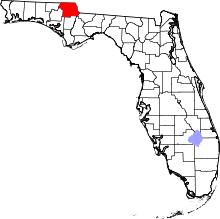

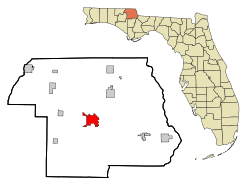

Location in Jackson County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 30°46′35″N 85°14′17″W / 30.77639°N 85.23806°WCoordinates: 30°46′35″N 85°14′17″W / 30.77639°N 85.23806°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| County | Jackson |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 16.85 sq mi (43.64 km2) |

| • Land | 16.80 sq mi (43.51 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) |

| Elevation | 167 ft (51 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,102 |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 9,052 |

| • Density | 363.2/sq mi (140.24/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 32446-32448 |

| Area code(s) | 850 |

| FIPS code | 12-43175[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0286422[4] |

| Website |

www |

Marianna is a city in Jackson County, Florida, United States. The population was 6,102 at the 2010 census.[5] In 2016 the estimated population was 9,052.[2] It is the county seat of Jackson County[6] and is home to Chipola College. The official nickname of Marianna is "The City of Southern Charm".

History

Marianna was founded in 1828 by Scottish entrepreneur Scott Beverege, who named the town after his daughters Mary and Anna.[7] It was named the county seat the following year, supplanting the earlier settlement of Webbville, which soon dissolved and no longer exists. Marianna was platted along the Chipola River, and many plantation owners from North Carolina relocated to Jackson County for the fertile soil.

Civil War era

John Milton was a major planter who owned the Sylvania Plantation and hundreds of slaves. He was elected as governor of Florida, serving during the Civil War years. Governor Milton was vehemently against the Confederate States of America rejoining the United States. He vowed that he would rather die than see the Confederates reunite with the northern states.

As federal troops were preparing to take control of Tallahassee, Governor Milton received word that the Civil War had ended and that Florida would, once again, be part of the United States. On April 1, 1865, as the southern cause was collapsing, Milton shot himself at Sylvania. In his last message to the legislature, he had said, "Death would be preferable to reunion." He was buried at Marianna.

Marianna was the site of a Civil War battle in 1864 between a small home guard of about 150 boys, older men, and wounded soldiers, and a contingent of approximately 700 Federal troops.

Reconstruction period

During the early years after the Civil War, violence flared in Marianna and Jackson County, where 150 to 200 Republicans, some black, were assassinated in what was known as the Jackson County War by members of the Ku Klux Klan in an effort to secure white supremacy.[8]:548–550 Locals claimed this was the work of "ruffians" from border states and carpetbaggers. Bishop Charles H. Pearce of Massachusetts, an AME minister who became a Florida state senator and had first-hand knowledge of the situation, placed the blame on the planters of Jackson County, who supported action against Republicans. Disputes over farm land caused much of the disorder, as poor whites objected to negro ownership of choice farms.[9]

Post-Reconstruction to mid-20th century

Violence continued in the state after Reconstruction, reaching a peak in most areas at the turn of the 20th century. From 1900 to 1930, Florida had the highest rate of lynchings per capita in the South and the nation. Refusing to accept the violence, thousands of African Americans left the state during the Great Migration, going to northern and midwestern industrial cities for other opportunities.

In 1934 Marianna was the site of the brutal torture and spectacle lynching of Claude Neal, an African-American man accused of rape and murder. The national publicity generated by the lynching, and resulting protests, played a significant role in making lynching less acceptable. But the Solid South in Congress consistently blocked passage of federal anti-lynching legislation.

After Neal's lynching, whites rioted as part of an effort by the KKK to expel all residents of Marianna who were identified as black; the governor called out the National Guard to suppress the violence. About 200 blacks and some police were physically hurt. The six white vigilantes who led the lynching remain unnamed.

In 1943 Cellos Harrison was taken from jail by a white mob and hanged (lynched) near Greenwood. His case had been in the courts for two years in appeals after he was arrested and twice convicted for the 1940 murder of a white man. He had confessed without benefit of counsel, and his convictions were overturned by the Florida Supreme Court as a result. But whites were tired of waiting and lynched him. President Franklin D. Roosevelt directed the Department of Justice to investigate Harrison's lynching; he felt it was terrible that blacks were getting lynched at home while the US was ostensibly fighting for freedom in Europe. But no one was ever prosecuted for Harrison's death.[10]

Florida School for Boys

The Florida School for Boys, a reform school operated by the state of Florida, was located in Marianna from January 1, 1900, to June 30, 2011. For a time, it was the largest juvenile reform institution in the United States. Throughout its 111-year history, the school gained a reputation for abuse, beatings, rapes, torture, and even murder of students by staff. Despite periodic investigations, changes of leadership, and promises to improve, the allegations of cruelty and abuse continued.

Many of the allegations were confirmed by separate investigations by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement in 2010 and the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice in 2011. State authorities closed the school permanently in June 2011. In 2015, an investigation by the University of South Florida revealed details of a secret "rape dungeon", where boys younger than 12 were sexually abused. It positively identified five bodies from remains recovered at the site.[11]

Geography

Marianna is located in central Jackson County at 30°46′35″N 85°14′17″W / 30.77639°N 85.23806°W (30.776370, -85.238149).[12] U.S. Route 90 passes through the center of town as Lafayette Street, leading east 14 miles (23 km) to Grand Ridge and west 9 miles (14 km) to Cottondale. Interstate 10 passes through the southern end of the city, leading east 65 miles (105 km) to Tallahassee, the state capital, and west 130 miles (210 km) to Pensacola. Access to Marianna is at Exit 136, Florida State Road 276.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.8 square miles (43.6 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 0.29%, are water.[1] The Chipola River, which forms the eastern border of the city, is part of the Apalachicola River watershed.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 356 | — | |

| 1860 | 440 | 23.6% | |

| 1870 | 663 | 50.7% | |

| 1880 | 586 | −11.6% | |

| 1890 | 926 | 58.0% | |

| 1900 | 900 | −2.8% | |

| 1910 | 1,915 | 112.8% | |

| 1920 | 2,499 | 30.5% | |

| 1930 | 3,372 | 34.9% | |

| 1940 | 5,079 | 50.6% | |

| 1950 | 5,845 | 15.1% | |

| 1960 | 7,152 | 22.4% | |

| 1970 | 7,282 | 1.8% | |

| 1980 | 7,006 | −3.8% | |

| 1990 | 6,292 | −10.2% | |

| 2000 | 6,230 | −1.0% | |

| 2010 | 6,102 | −2.1% | |

| Est. 2016 | 9,052 | [2] | 48.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 6,230 people, 2,398 households, and 1,395 families residing in the city. The population density was 776.1 inhabitants per square mile (299.6/km²). There were 2,764 housing units at an average density of 344.3 per square mile (132.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 56.8% White, 40.2% African American, 0.3% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.9% from other races, and 1.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.6% of the population.

There were 2,398 households out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.3% were married couples living together, 20.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.8% were non-families. 38.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 19.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.22 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the city, the population was spread out with 26.7% under the age of 18, 11.8% from 18 to 24, 22.3% from 25 to 44, 18.4% from 45 to 64, and 20.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,861, and the median income for a family was $29,590. Males had a median income of $28,500 versus $21,530 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,021. About 20.9% of families and 28.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.7% of those under age 18 and 34.6% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure

The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice Dozier School for Boys was located in Marianna.

Education

Jackson County School Board operates public K-12 schools. Marianna has five schools, all of which usually perform in the high C-low B range in the state's FCAT grade scale. Golson for grades K-2, Riverside Elementary for grades 3-5, Marianna Middle School for grades 6-8, and Marianna High School for grades 9-12.

Chipola College, home of the Chipola Indians, is the choice for many residents and offers dual-enrollment classes for high school students. The college is a four-year state institution offering bachelor's degrees in nine programs. Additionally, students can earn masters and doctoral degrees on the Chipola Campus through Troy State University, University of Florida, University of West Florida, and Florida State University.

From 1961 to 1966, a junior college, Jackson Junior College, served African-American students. It closed in 1966 after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the opening of Chipola Junior College (today Chipola College) to all students.[14]

Transportation

Marianna Municipal Airport, a former World War II Army Air Corps base, is a public-use airport located 4 miles (6.4 km) northeast of the central business district. The city is also served by J-trans, a bus transit system that runs through the whole city.

Attractions

Marianna is an official Florida Main Street town. The downtown area has been restored to look as it did many years ago, to encourage heritage tourism and emphasize its unique character and a pedestrian-friendly neighborhood. The downtown area includes the Marianna Historic District, which has a number of antebellum homes.

Florida Caverns State Park is located 2 miles (3 km) north of town. There is also cave diving in underwater Blue Springs. St. Luke's Episcopal Church and cemetery are state landmarks, as they had a principal role in the U.S. Civil War battle of Marianna in 1864. The Chipola River is a source of recreation during all but the winter months.

.jpg)

Notable people

- Monnie T. Cheves, former assistant to president of Chipola College, member of Louisiana House of Representatives from 1952 to 1960[15]

- Cliff Ellis, basketball head coach, Coastal Carolina University, born in Marianna

- Bobby Goldsboro, pop and country singer-songwriter, born in Marianna[16]

- David Hart, actor, TV series In the Heat of the Night

- Caroline Lee Hentz, novelist and author

- Danny Lipford, home improvement expert

- Moss Mabry, Academy Award-nominated costume designer

- Jeff Mathis, professional baseball player

- John Milton, governor of Florida during the Civil War

- Claude Neal, African American victim of torture and spectacle lynching in 1934 after being accused of rape

- Sam E. Parish, 8th Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force

- Rick Pearson, professional golfer

- Wankard Pooser, politician

- Jim Sorey, professional football player

- Ret Turner, Emmy Award-winning costume designer

References

- 1 2 "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 7, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Marianna city, Florida". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 442

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Wasserman, Adam (2010). A People's History of Florida 1513–1876. How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State (4th ed.). Sarasota, Florida. ISBN 9781442167094.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 443

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Tameka Bradley Hobbs, Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home, Oxford University Press, 2015

- ↑ Luscombe, Richard (6 February 2015). "'Rape Dungeon' Allegations Emerge in Abuse Report on Dozier School for Boys". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Walter L. Smith, The Magnificent Twelve: Florida's Black Junior Colleges, Winter Park, Florida, FOUR-G Publishers, 1994, ISBN 1885066015, pp. 211-225.

- ↑ "In Memoriam: Monnie T. Cheves". Alexandria, Louisiana: Alexandria Daily Town Talk. August 17, 1988. p. D3. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (1996). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Country Hits, pp.128–29. ISBN 0-8230-7632-6.

External links

![]()